By Ray Williams

November 2, 2020

An executive at JPMorgan Chase & Co. gets unapologetic messages from colleagues on nights and weekends, including a notably demanding one on Easter Sunday. A web designer whose bedroom doubles as an office has to set an alarm to remind himself to eat during his non-stop workday. At Intel Corp., a vice president with four kids logs 13-hour days while attempting to juggle her parenting duties and her job.

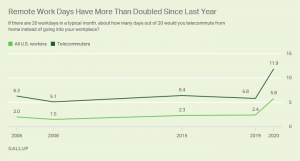

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many people have shifted to remote and virtual work, which has impacted women and families the most. The boundary between work and home is rapidly disappearing.

One impact has been the length of the working day. Prior to the pandemic, there have been significant initiatives to reduce the length of the working day and working week. With the pandemic, we are heading in the opposite direction.

The National Bureau of Economic Research commissioned researchers from Harvard Business School and NYU Stern School of Business, who used anonymized email data to analyze the work habits of more than 3 million people spread out among 16 cities that were locked down. Their conclusion: People worked an average of 48.5 minutes more per day, compared with the pre-virus period.

People are working longer hours in the wake of the global coronavirus pandemic and the mass increase in remote work. New data from NordVPN Teams show not only a massive spike in business VPN usage but also people working on average two hours longer than usual.

Working Hours: Country Comparisons (NordVPN Teams)

| Country | Before COVID-19 | Now |

| UK | 9 | 11 |

| US | 8 | 11 |

| France | 8 | 10 |

| Germany | 9 | 10 |

| Netherlands | 9 | 10 |

| Belgium | 9 | 10 |

| Spain | 6 | 10 |

| Canada | 9 | 11 |

| Austria | 9 | 10 |

| Italy | 8 | 8 |

The U.S. increased its average workday by almost 40%, adding an extra three hours, the largest jump worldwide. The UK, France, Canada, and Spain are seeing a two-hour increase.

Through an analysis of the work cadence data of 40,000 paid organization accounts, the Microsoft-owned company revealed in a report that developers on the GitHub platform are working an additional 30 to 60 minutes per day since March.The report also revealed that more developers have extended their work hours into the weekend during the pandemic. They are also not merely stretching their workdays longer while performing the same volume of work, but rather, users are consistently increasing their work volume compared to the same period last year.

Now, well into a nationwide work-from-home experiment with no end in sight, whatever boundaries remained between work and life have almost entirely disappeared.

With many living a few steps from their offices, America’s always-on work culture has reached new heights. The 9-to-5 workday, or any semblance of it, seems like a relic of a bygone era. Long gone are the regretful formalities for calling or emailing at inappropriate times. Burnt-out employees feel like they have even less free time than when they wasted hours commuting. Employees are also logging back in late at night. Surfshark, another VPN provider, has seen spikes in usage from midnight to 3 a.m. that were not present before the COVID-19 outbreak.

Huda Idrees, the CEO of Dot Health, a Toronto-based technology startup, confirms her 15 employees are working on average, 12-hour days up from 9 hours pre-pandemic. “We’re at our computers very early because there’s no commute time,” she said. “And because no one is going out in the evenings, we’re also always there.”

The lengthening workday began even before lockdowns were officially announced, the researchers found — an indication that workers and companies were scrambling to adjust in preparation of formal work-from-home orders.

The findings add to other evidence that working from home — while protecting employees from exposure to COVID-19 — also points to new sources of stress. Many employers have implemented productivity-tracking systems for newly remote workers. Even in the absence of formal metrics, employees may feel pressured to compensate for a lack of face-to-face time with their colleagues by being more visible online.

“It doesn’t seem like telecommuting is used by people to replace work hours. When people telecommute, they use it mostly to do more work,” according to Mary Noonan, a sociologist at the University of Iowa. A 2017 study she co-authored comparing onsite and remote workers at the same company found that telecommuters do three more hours of unpaid work a week than their on-site colleagues.

During lockdowns, workers also end up sending more emails and holding more meetings, the researchers found. However, the meetings were shorter than usual, with the result that total time spent in meetings actually decreased during the lockdown.

Since the lockdowns ended, some cities have returned to more typical work patterns. Workdays in Chicago, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., have since returned to pre- lockdown lengths, according to the paper. But employees in cities such as New York and San Francisco in the U.S. and London, Madrid and Rome in Europe are still working longer than typical hours.

Many businesses have announced plans to extend the work-from-home regime. Twitter says its 5,000 employees can work remotely “forever,” while Facebook expects that fully half its workforce will work from home within a few years. A recent Gartner survey found that more than 80% of company leaders plan to have their staff work remotely at least part-time.

But as the NBER paper concludes, working from home can be a double-edged sword. “On one hand, the flexibility to choose one’s working hours to accommodate household demands may empower employees by affording them some freedom over their own schedule, and on the other hand, working from home can extend workers’ working day, which creates its own stresses.”

One big problem is there’s no escape. With nothing much to do and nowhere to go, people feel like they have no legitimate excuse for being unavailable. One JPMorgan employee interrupted his morning shower to join an impromptu meeting after seeing a message from a colleague on his Apple Watch. By the time he dried off and logged back on, he was five minutes late.

Then there’s the fact that people have turned their living spaces into makeshift offices, making it nearly impossible to disconnect. Having an extra room helps, but not much, said one financial compliance employee of a manufacturing company. His workspace is right next to the living room. “You walk by 20 times a day” he said. “Every time you pass there, you’re not escaping work.”

By early April, about 45% of workers said they were burned out, according to a survey of 1,001 U.S. employees by Eagle Hill Consulting. Almost half attributed the mental toll to an increased workload, the challenge of juggling personal and professional life, and a lack of communication and support from their employer. Maintaining employee morale has proved difficult, said two-thirds of human resources professionals surveyed by the Society for Human Resource Management earlier this month.

Those crammed into smaller quarters are also at a higher risk of developing high blood pressure than colleagues with extra rooms, according to preliminary research by Tessa West, an associate professor of psychology at New York University.

Parents with kids at home are stretched particularly thin, as they squeeze work in between child-care duties, which now include virtual learning sessions. In two-thirds of married couples with children in the U.S., both parents work, leaving nobody available to watch the children.

This increase in the working day because of COVID-19 has come while the merits of the 8-hour working day was being seriously questioned.

How the 8-Hour Workday was Under Scrutiny

An eight-hour work day has it origins in the 16th century, but the modern movement dates back to the Industrial Revolution in Britain, where industrial production in large factories transformed working life. At that time, the working day could range from 10 to 16 hours, the work week was typically six days a week and the use of child labour was common.

What has happened to the perennial predictions of a leisure society and escape from long hours of work? In the late 1700’s, Benjamin Franklin predicted we’d work a 4-hour week. In 1933 the U.S. Senate passed a bill for an official 30-hour workweek, which was vetoed by President Roosevelt. In 1965, a U.S. Senate subcommittee predicted a 22-hour workweek by 1985 and a 14- hour work week by 2000.

In his 1930’s essay “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted a 15-hour workweek in the 21st century, creating the equivalent of a five-day weekend. “For the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem,” Keynes wrote, “how to occupy the leisure.”

In a 1957 article in The New York Times, writer Erik Barnouw predicted that, as work became easier, our identity would be defined by our hobbies, or our family life. “The increasingly automatic nature of many jobs, coupled with the shortening work week [leads] an increasing number of workers to look not to work but to leisure for satisfaction, meaning, expression,” he wrote.

The economists of the early 20th Century did not foresee that work might evolve from a means of material production to a means of identity production. They failed to anticipate that, for the poor and middle class, work would remain a necessity, but for the college-educated elite it would morph into a kind of religion, promising identity, transcendence and community.

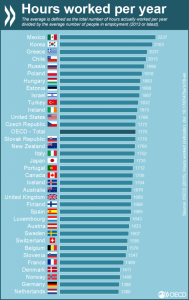

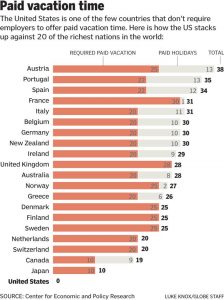

Atlantic staff writer Eric Thompson contends the American dream–“that mythology that hard work always guarantees upward mobility has for more than a century made the U.S. obsessed with material success and the exhaustive striving required to earn it.” Thompson points out that no large country in the world as productive as the U.S. averages more hours of work per year. And the gap between the U.S. and other developed countries is growing. Between 1950 and 2012, he says, annual hours per employee fell by about 40% in Germany, France and the Netherlands, but increased in the U.S.

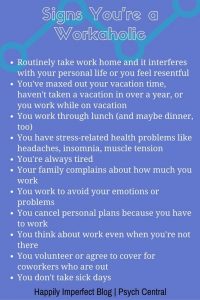

A discussion about the 8-hour workday would not be complete without examining the connected issue of workaholism.

Workaholism

In Japan they call it “karoshi” and in China it is “guolaosi.” As yet there is no word in English for working yourself to death, but as more and more people put in longer hours and suffer more stress there may soon be.

Ronald Reagan was wrong, when he said: “Hard work never killed anyone,” particularly curious from a man who was known not to work very hard. Death from overwork is not a new phenomenon in Western countries but it is largely unremarked upon. In 1987, the Japanese ministry of labor acknowledged that it had a problem with death from overwork and began to publish statistics on karoshi. In 2001, the numbers reached a record level with 143 workers dying. Now, death-by-overwork lawsuits are common, with the victims’ families demanding compensation payments. Overwork was popularly blamed for the fatal stroke of Prime Minister of Japan Keizō Obuchi in 2000, and in 2013, a Bank of America intern in London died after working for 72 hours straight.

.

A workaholic is a person who works compulsively often at the expense of other pursuits. While the term generally implies that the person enjoys their work, it can also alternatively imply that they simply feel compelled to do it. There is no generally accepted medical definition of such a condition, although some forms of stress, impulse control disorder and obsessive-compulsive tendencies.

“It’s easy to miss the signs,” says Ronald Burke, professor of organizational behavior at the Schulich School of Business, York University, in Toronto. “Work addicts are rewarded, valued members of an organization. But what’s going on in their deepest souls, the signs of pain are not visible.”

There is mixed information on whether there is there a relationship between workaholism and laws governing hours of work. For example, in Korea, the 40-hour work week is legally mandated, but most Koreans work far more than that. In general, Asian countries have longer work weeks. All European nations have shorter work weeks (except Britain) than the United States or Canada. However, at least 134 countries have laws setting a maximum length. The U.S. does not. According to the OECD, 85.8% of males and 66.5% of females work more than 40 hours a week. According to the ILO, Americans work 137 more hours a year than Japanese workers, 260 more than British workers and 499 more than the French.

Overachieving professionals today are seen as road warriors, masters of the universe. They work harder, take on endless additional responsibilities and earn a lot more than their counterparts in earlier times, and their numbers are growing. And it is these individuals who bring into clear focus the question of work-life balance. Although the manifestations of workaholism are at the level of the individual, workaholic behavior is socially acceptable and even encouraged by major organizations.

The constant chase can make even the most seasoned executives feel overwhelmed. “Busyness is not a means to accomplishment, but an obstacle to it,” writes Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, a Stanford scholar and author of Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less. He argues in his book that when we define ourselves by our “work, dedication, effectiveness and willingness to go the extra mile,” it’s easy to think that doing less and creating more peace in our minds are barriers to success.

Workaholism and Social Media

Since the physical world leaves few traces of achievement, today’s workers turn to social media to make manifest their accomplishments. The social media feed is evidence of the fruits of hard, rewarding labor and the labor itself. Among Millennial workers, it seems, overwork and “burnout” are outwardly celebrated (even if, one suspects, they’re inwardly mourned).

The problem with this gospel — Your dream job is out there, so never stop hustling — is that it’s a blueprint for spiritual and physical exhaustion. Long hours don’t make anybody more productive or creative; they make people stressed, tired and bitter. But the overwork myths survive because they justify the extreme wealth created for a small group of elite techies.

Articles in mainstream and social media are replete with exhortations about how you can only be successful if you become a workaholic. Here are the titles of popular articles: “Why Hard Work is the Key to Success.”“5 Reasons You Need to Work Hard to Get Ahead.” These articles are often accompanied by stories or quotations from famous workaholics like Steve Jobs or Elon Musk who just 24 hours after admitting that he’d almost worked himself to death while making Tesla profitable, he tweeted “There are way easier places to work, but nobody ever changed the world on 40 hours a week.”

Here’s some other famous examples that are often held up as desirable models of work: Steve Jobs left incredibly big shoes for CEO Tim Cook to fill. However, the man got the top job for a reason. He’s always been a workaholic, and Fortune reports that he begins sending emails at 4:30 a.m. A profile in Gawker reveals that he’s the first in the office and the last to leave. He used to hold staff meetings on Sunday night in order to prepare for Monday. Mark Cuban writes on his blog that it took an incredible amount of work to benefit from his luck. When starting his first company, the now billionaire routinely stayed up until 2 a.m. reading about new software, and went seven years without a vacation.

The early days at Amazon were characterized by Jeff Bezos working 12-hour days, seven days a week, and being up until 3 a.m. to get books shipped.

A profile in Forbes describes how Nissan and Renault CEO Carlos Ghosn worked more than 65 hours a week, spent 48 hours a month in the air, and flew more than 150,000 miles a year.

Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer routinely used to put in 130-hour weeks at Google, according to Entrepreneur, a schedule she managed by sleeping under her desk. Even people critical of her management style acknowledge that she “will literally work 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Business Insider’s Rich Carlson reports.

GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt spent 24 years putting in 100-hour weeks. A 2005 Fortune article on Immelt describes him as “the Bionic Manager.” The article highlights his incredible work ethic, saying he worked 100-hour weeks for 24 years

The Case for Shorter Week Days and Shorter Work Weeks

Steve Glaveski, writing in the Harvard Business Review, observes, “The internet fundamentally changed the way we live, work, and play, and the nature of work itself has transitioned in large part from algorithmic tasks to heuristic ones that require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity.” Glaveski reports, he “conducted a two-week, six-hour workday experiment with my team at Collective Campus, an innovation accelerator based in Melbourne, Australia. The shorter workday forced the team to prioritize effectively, limit interruptions, and operate at a much more deliberate level for the first few hours of the day.

Employees at eXO Skin Simple work what they call “Swiss hours,” from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Clarke Bowling, the company’s digital marketing manager, said in an NBC News article that the schedule gives employees plenty of time to get their work done without wasting time.

Tower Paddle Boards found similar success after shifting to five-hour workdays, without cutting salaries or benefits. Its employees work from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. each day, eliminating lunch breaks that usually take longer than they should and leave workers in food comas during the afternoon.

Sweden has experimented with six-hour workdays, for both government operations and private companies, with some success.

Earlier this year, a New Zealand company called Perpetual Guardian, which staffs about 240 people, decided to test a 4-day work week for two months in which employees work four 8- hour days but get paid for five. Extensive research was done on this 2-month project in an effort to calculate the effects and changes to work-life balance and productivity.

Well, guess what? The results are in. And they paint a picture of an unmitigated success.

As a result of the trial, staff stress levels decreased by 7 percent. The percentage of employees who said they were able to successfully manage their work-life balance increased from 54% to 78%. And overall life satisfaction increased by 5 percentage points.

In a 2012 op-ed in the New York Times, software CEO Jason Fried reported that the 32-hour, four- day workweek his company follows from has resulted in an increase in productivity.“ Better work gets done in four days than in five,” he wrote. It makes sense: When there’s less time to work, there’s less time to waste. In fact, over a third of employees admitted they’re productive for less than 30 hours a week in a recent study conducted with over 3,500 workers. That’s a whole day each week that they’re in work, but not working.

Here’s 7 reasons why working less might mean getting more done:

Parkinson’s Law: ‘Working longer hours doesn’t increase efficiency.’ Parkinson’s Law states that ‘work expands to fill the time available for its completion’. Whether you’ve been conscious of it or not, we’ve all experienced Parkinson’s Law. The way our brains are wired means that the longer we have to complete a task, the more time we have to procrastinate and overthink the task, often just filling that time with stress and anxiety about having to get it done.

Working to the point of exhaustion leads to mistakes. We all know that when we’re tired we’re not quite at the top of our game; but people close to burnout or suffering from exhaustion will make errors. They also don’t have the same control over their emotional health so may make rash decisions or not make a decision quickly enough, something which can cost the business with a missed opportunity.

Six-hour days result in less sick days. In the Swedish city of Gothenburg a two-year trial of a six-hour working day at a care home proved that a shorter working day lowered sick leave by 10%. Other perceived health benefits of the care workers were reductions in stress and increased alertness. The residents at the care home also reported that they felt they were getting better care and more time with the nurses. Overworked people tend to eat more, stress more, and exercise less; if this becomes a continuous cycle it can create a myriad of underlying health issues.

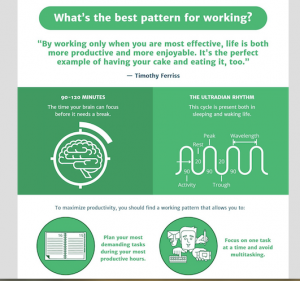

Our brains aren’t wired for more than four hours of serious focus a day. According to science, four hours of work a day is the maximum our brains can handle. We are talking proper, serious, focused work; not just sitting in meetings or sending emails.

Almost no one is “working” for eight hours a day. It doesn’t matter how long you spend working, chances are you aren’t working productively for eight hours a day. Instead, data and surveys from around the world have found that modern workers are only truly productive for a maximum of 2 hours and 50 minutes a day. But what about the other five-plus hours? They’re spent on non-work activities like reading the news or social media, socializing with coworkers, taking breaks, or lost to multitasking, context switching, and endless non-productive meetings.

The quality of work (and happiness) drops sharply after a certain number of hours.Even if you try to work more to make up for those lost hours, your productivity will hit a wall. According to research from Stanford University, output and creativity sharply decline after 50 hours of working in a week. And it only gets worse the more you work. In fact, people who work a 70-hour workweek are likely to produce nothing during those 15–20 extra hours.

Our focus is limited to blocks of 20–90 minutes at a time maximum.The problem with long workdays isn’t just that we’re spending too long at work. It’s that we’re trying to spend all that time productively. The human brain is more like a muscle than a computer. You can’t load it up with tasks without giving it breaks and proper time to recover. research shows that attention spans begin to decay significantly after 20 minutes while most people require a break every 50–90 minutes. (If you want to get technical, our brains go through something called ultradian rhythms every 90 minutes after which we need to take a break.) A study recently conducted by the Draugiem Group used a computer application to track employees’ work habits. Specifically, the application measured how much time people spent on various tasks and compared this to their productivity levels. In the process of measuring people’s activity, they stumbled upon a fascinating finding: the length of the workday didn’t matter much; what mattered was how people structured their day. In particular, people who were religious about taking short breaks were far more productive than those who worked longer hours. The ideal work-to-break ratio was 52 minutes of work, followed by 17 minutes of rest. People who maintained this schedule had a unique level of focus in their work. For roughly an hour at a time, they were 100% dedicated to the task they needed to accomplish. They didn’t check Facebook “real quick” or get distracted by emails. When they felt fatigue (again, after about an hour), they took short breaks, during which they completely separated themselves from their work. This helped them to dive back in refreshed for another productive hour of work.

How to Build a New-Normal WorkdayThat’s Not Based on 8-hours

Track Your Working Time

So how do you create a shorter new-normal workday schedule that actually works? Unfortunately, creating a new schedule isn’t as simple as just saying you’ll work fewer hours. There are forces at play — both internal and external — that will make it incredibly hard to stick to your new normal, even if you know it’s better for your health, productivity, and creativity.

The software RescueTime helps teams and individuals take back control of their day. Start by understanding your productivity baseline (i.e., know what a “good day” looks like). What gets measured gets improved: If you want to save money, you track your spending. If you want shorter, more efficient workdays, you need to track your time. Time tracking is a great tool for understanding where your time is going, uncovering distractions, and building a better schedule. But more important, tracking your time helps you understand what a good day actually looks like for you. RescueTime automatically observes and tracks everything you do on your digital devices to give you detailed reports on how long you spend on specific apps, websites, and projects, as well as help you uncover trends in your productivity.

Rewire Your Brain for Focus. Even if you’re working eight-plus hours a day, you’re probably lucky to get two-plus hours of time for your most important work. But this is good news. As Alex Pang, author of Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less, told us: “Two hours where you can really get into the problem yields solutions that are going to be better than if you spent 10 hours broken up by meetings and bouncing around on Slack channels.” The key difference is in your ability to focus. Single-tasking and focusing for long periods of time are superpowers. In fact, some researchers say that a highly focused hour is up to 500% more productive than one where you bounce between tasks, emails, and calls. Set aside time for focused work and stick to it. This means blocking distracting websites that tempt you (FocusTime is a great tool for this) and keeping your email/chat/phone on DND mode.

Schedule Your Day Around Your Peak Productive Hours. With your priorities straight, hard data on when you work best, and a commitment to focus, it’s time to build your shorter, new- normal schedule. But just as important as how much you work is when you work. One study has shown that the most productive part of the day for most people is between 8 and 11 am, with the afternoons and evenings reflecting some decline in cognitive functioning.

Set Limits on Communication Time . Communication is key to a healthy workplace. But the always-on nature of chat, video calls, and email means work never ends. To keep up with your new schedule, set limits on your communication time, or make yourself available only during specific times of the day. This is known as “bursty” communication — meaning you alternate between times of deep work and deep conversation. According to studies, this is the best way for teams to stay productive and innovative.

Embrace Active Rest. Our brains need downtime during the day to recover and refocus. However, we also need downtime outside of work to be at our best. Your overall well-being, creativity, and even productivity depend on a healthy default-mode network. This is the part of the brain that activates when you’re “doing nothing.” A large part of a healthy new-normal work schedule is giving yourself permission to not work.

Break your day into hourly intervals. We naturally plan what we need to accomplish by the end of the day, the week, or the month, but we’re far more effective when we focus on what we can accomplish right now. Beyond getting you into the right rhythm, planning your day around hour-long intervals simplifies daunting tasks by breaking them into manageable pieces. If you want to be a literalist, you can plan your day around 52-minute intervals if you like, but an hour works just as well.

Renegotiate Family Norms Regarding Sharing of Space, Time and Responsibilities. COVID-19 has resulted in children being at home and not at school, and many mothers having to abandon or modify their careers for childcare. Fathers will need to step up and share more of the responsibility for childcare and domestic responsibilities.

How COVID-19 Has Impacted Families and Particularly Women

But it isn’t really that everyone in the COVID-19 economy can’t have a child and a job at the same time. It’s that mothers, specifically, cannot. It is mothers, not fathers, who have historically shouldered the vast majority of the childcare burden, and continue to do so during the pandemic, according to one New York Timessurvey; it is women, not men, for whom the Secretary General of the United Nations warned, “across every sphere, from health to the economy, security to social protection, the impacts of COVID-19 are exacerbated.” It is mothers, not fathers, who have historically bowed out of the workforce when their domestic responsibilities increase, thus making it more difficult for them to ever return.

It is women, not men, who will take pay cuts and buyouts, who will go from full-time to part-time to no-time. In many respects, this is an unprecedented historical moment, says Stephanie Coontz, director of research and public education for the Council on Contemporary Families. Although mothers have been expected to juggle domestic labor with work for much of history, they were reliant on their communities — for instance, grandparents or neighbors — to assume some of the childcare when they were too busy. “There was this integrated community of work, education, instruction, and exchange that was very hard work, but it wasn’t this isolated work,” she says. While weepy, coronavirus- themed Facebook commercials may try to convince us that social media and virtual interaction can supplant the loss of this network, “they don’t have the actual physical coordination and the interdependence that parents really need,” she says. In other words, the COVID-19 pandemic has ushered in an era where parents, particularly women, are expected to achieve a perfect balance between work and childcare, and for basically the first time in human history, they’re expected to do it on their own.

Unsurprisingly, many experts have predicted that this doesn’t bode super well for women. A report from the United Nations has warned that the precarious economic situation could “roll back” many of the advances feminism has made over the past few decades, with layoffs hitting women disproportionately or forcing women with small children to bow out of the workforce. “We could have an entire generation of women who are hurt [economically],” Betsey Stevenson, a professor of economics and public policy at the University of Michigan, told theNew York Times.

It’s worth noting, that compared to many low-income women and women in service industries, middle-class working mothers who have the luxury of working from home are in a position of extraordinary privilege. While there is little hard data on the subject, low- income mothers will also be hardest hit by the impact of the pandemic: “If you’re making less money in a relationship and men make more, what’s happening is women are staying at home to cover for childcare and these are often low-income women,” says Ellen Kossek, a professor of management at Purdue University Krannert School of Management and author of a forthcoming study on the subject.

Virtually any working mother has a horror story about feeling pushed out of the workplace pre-COVID-19, even those who come from a relative position of privilege, because the demands of the American workplace are totally antithetical to the demands of the home.

Over the past few months in the U.S., policy makers have engineered what they no doubt view as ingenious ways to return children back to school, all of which have been met with widespread ire from parents on social media. Employers have also done their part in instituting policies that are wildly ignorant of, if not downright hostile to, the lived realities of working parents, with Florida State University instituting a policy for remote employees banning them from caring for children while working. “[FSU IS] acting like they gave us this privilege to watch our children while we worked — when that’s literally what I had to do,” one professor complained. (FSU walked back on this policy following backlash on social media, sending an email to staff saying, “We want to be clear — our policy does allow employees to work from home while caring for children.”)

That the needs of parents were not taken into account during the development of these policies is apparent; that the needs of working mothers in particular were not considered, doubly so. In the absence of these discussions, the onus has been on parents themselves, not employers or policy-makers or the media. “There’s a stigma right now that you cant say ‘I’m not available because I’m helping my kid with my homework from 2-3,’ and you have to empower people to do that especially during the pandemic,” says Kossek. Though she says managers should lead these conversations, the reality is that they so frequently fall on employees that it’s clear women aren’t just expected to seamlessly perform childcare and household and work duties simultaneously, they’re also expected to start the conversation about why such expectations are unfair.

Therein lies the crux of the issue: although much valuable discussion has been devoted to how COVID-19 has exposed the disparities in class, gender, and income, the parenting issue intersects with all three of those things, yet receives relatively little attention.

There are some who are optimistic about the long-term changes that COVID-19 may bring in terms of gender dynamics and parenting. In the long run we know that when men learn to actually get hands-on experience with the kind of work they were able to ignore for so long, they do do better Kossek says, citing studies that show how men who take paternity leave end up assuming more of the burden of household labor. Now that men have been forced to pick up some of the childcare burden, becoming more intimately acquainted with its accompanying gifts and travails, “I think there may be some possibilities for forward progress after this,” she says.

Summary:

The COVID-19 pandemic has ushered in changes in the way we work. Unfortunately, one of those changes has been an increase in the 8-hour workday, just when organizations, backed by researched studies were moving to reduce the workday and workweek. And COVID-19 has place enormous pressure on families, particularly women, to shoulder the burdens of new working arrangements. How governments and organizations emerge from COVID-19 will determine if we move forward to more beneficial work-life arrangements or go back in to less productive and beneficial times.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.