We all want an apology when someone does us wrong. Are the apologies effective? From the person giving the apology, it may be assumed so. From the perspective of the person receiving, it, maybe not. But showing changed behavior may be more convincing.

Why do people or institutions apologize?

One common reason given for why people apologize is “negative affect alleviation.” People feel guilty, and an apology removes the guilt? This view dates to a Freudian model of human behavior where humans have a residue of emotion—in this case, guilt—which when accumulated, causes distress until emptied. In the book Mea Culpa: A Sociology of Apology and Reconciliation, Nicholas Tavuchis sees apologies as a complex social system designed to maintain relationships and establish membership in community, a kind of social exchange that restores social order.

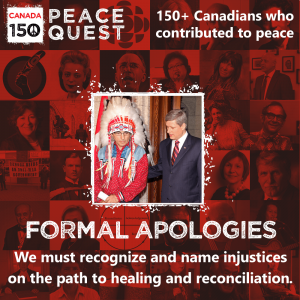

Apologies as a fundamental part of a healthy society are important for several reasons. First, they can mend or heal damaged or broken relationships either between individuals, or even groups of people or countries. Second, apologies can provide an opportunity for the transgressor to either amend their reputation, or provide assurances that the transgression is not a reflection of a pattern of behavior, and therefore not likely to be repeated in the future.

Successful consummate apologies may raise the moral threshold of a society because they promote positive externalities such as increased trust and mutual respect. It is in such a milieu that previously disempowered individuals and groups are using their elevated status to remind others of profound inequities and insult. Apologies are a civilized way to redress these inequities. The motives behind an apology reveal what role an apology plays or, at least, what it might achieve, for the person delivering it. An apology is a peace offering; an act of humility and humanity; a moderating force in the face of retribution; and a mental salve. The person who receives an apology — if it satisfies his or her expectations — can also experience significant benefits. An apology is a social transaction that involves a significant exchange of power, an exchange that is crucial for the restoration of balance and harmony.

Michael E. McCullough, Ph.D., Steven J. Sandage, M.S., and Everett L. Worthington Jr., Ph.D., examined whether the effect of apology on our capacity to forgive is due to our increased empathy toward an apologetic offender. They discovered that much of why people find it easy to forgive an apologetic wrongdoer is that apology and confession increase empathy, which heightens the ability to forgive. McCullough, who is the director of research at the privately funded National Institute for Healthcare Research in Rockville, Maryland, believes that apology encourages forgiveness by eliciting sympathy. He and his colleagues published research in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology that supports this hypothesis.

A study, published in Psychological Science, finds that people aren’t very good at predicting how much they’ll value an apology. Apologies have been in the news a lot the last few years in the context of the financial crisis, says David De Cremer of Erasmus University in the Netherlands. He co-wrote the study with Chris Reinders Folmer of Erasmus University and Madan M. Pillutla of London Business School. “Banks didn’t want to apologize because they didn’t feel guiltybut, in the public eye, banks were guilty,” De Cremer says. But even when some banks and CEOs did apologize, the public didn’t seem to feel any better. “We wondered, what was the real value of an apology?”

De Cremer and his colleagues used an experiment to examine how people think about apologies. Volunteers sat at a computer and were given 10 euros to either keep or give to a partner, with whom they communicated via computer. The money was tripled so that the partner received 30 euros. Then the partner could choose how much to give back-but he or she only gave back five euros. Some of the volunteers were given an apology for this cheap offer, while others were told to imagine they’d been given an apology.

The people who imagined an apology valued it more than people who actually received an apology. This suggests that people are pretty poor forecasters when it comes down to what is needed to resolve conflicts. Although they want an apology and thus rate it as highly valuable, the actual apology is less satisfying than predicted.

“I think an apology is a first step in the reconciliation process,” De Cremer says. But “you need to show that you will do something else.” He and his authors speculate that, because people imagine that apologies will make them feel better than they do, an apology might actually be better at convincing outside observers that the wrongdoer feels bad than actually making the wronged party feel better.

A study from the University of Pennsylvania offers some insight into the psychology of trust-both violation and repair. Psychological scientist Maurice Schweitzer, an expert on organizations and decision making, decided to explore the idea of trust recovery in the lab. He and his colleagues-Michael Haselhuhn and Alison Wood-wanted to see if basic beliefs about moral”character” influence trust violations and forgiveness. They also wanted to see if they could modify those beliefs-and in doing so make people more or less forgiving.

The scientists recruited a large group of volunteers to play an elaborate game involving breaches of trust and reparations. But before the game started, they primed the volunteers with different beliefs about moral character. Some were nudged to believe that people can change-that people can and do become more ethical and trustworthy if they sincerely set their minds to it. The others were primed with the opposite belief-basically that scoundrels will always be scoundrels. This core belief is surprisingly easy to manipulate, and the researchers did it here simply by having the volunteers read essays arguing for one belief or the other.

The trust game that followed goes like this: You have $6, which you can either keep or give to another person. If you give it away, it triples in value to $18, which the recipient can either keep or split with you, $9 apiece. So initially giving away the $6 is obviously an act of trust. But in order to study trust recovery, the scientists put the volunteers through several rounds of the game. In the early rounds, the recipient (actually a computer) violated trust by keeping the $6 a couple times in a row. Then the recipient apologized and promised to be more trustworthy from now on. Then there was one final opportunity to be either trusting or not.

So does believing in the possibility of change shape people’s ability to forgive-and trust again? It does, dramatically. As the scientists reported in the journal Psychological Science, they easily eroded trust and they also easily restored it-but only in those who believed in moral improvement. Those who believed in a fixed moral character, incapable of change, were much less likely to regain their trust after they were betrayed.

These results have practical implications for anyone trying to make amends and reestablish trust-in recovery, in business, in love-and yes, in politics. Apologies and promises may not be enough in some cases, and indeed it may be more effective to send a convincing message about the human potential for real moral transformation. The best way to send that message, of course, may be to act like a changed person.

The Elements of an Effective Apology

Considerable psychological and other research have identified the essential elements of a good apology, which can be applied to both an individual or institutional circumstance: The transgressor must be genuinely remorseful. An apology should not be forced or insincere. If it is, it will often be seen that way, lose it’s impact, or not be accepted or believed.

- The transgressor should deliver the apology with honesty and vulnerability. When the transgressor is willing to share their emotions honesty about the mistake, the impact on others carries greater credibility and emotional significance.

- The transgressor takes personal and full responsibility for their actions and behavior. This means no equivocations, excuses or “non-apologies.”

- The transgressor explains that they did and the reasons why it was wrong. This also includes admitting the negative impact the mistake has made on others. This is not the same as providing excuses or rationalizations, but rather an honest admission of the process by why the transgressor made the mistake.

- The transgressor uses “I” statements (or in the case of an institution the individual(s) indicating personal responsibility and avoiding vague reference or projecting blame on others or circumstances.

- The transgressor actually uses the words “I am sorry.” Again, modifiers or language that can essentially avoid personal responsibility such as “It’s unfortunate,” “it’s a sad situation that.”

- The transgressor offers to or makes amends. This means committing to actions that are a promise or commitment of non-repetition or offering to something to correct the injury or harm done.

- The transgressor asks for forgiveness. This can be a controversial element for severalreasons. First, if the request for forgiveness early may or may not help the victim or situation. Timing is of the essence. Second, asking for forgiveness should not be used as a manipulative tool to absolve the transgressor of responsibility to make amends.

- The transgressor forgives themselves. Part of the process of healing is to more effectively deal with the problem of guilt without removing the need for remorse. The transgress needs to heal as well.

If for some reason, the transgressor can’t craft an apology with all six components, the researchers say, the most important element is accepting responsibility. Acknowledging that the transgressor made a mistake and make it clear that they were at fault is necessary. The researchers also argue the transgressor should never apologize for the injured party’s feelings, but rather take full responsibility for the transgressor’s behavior. For example, rather than say, “I’m sorry if you were hurt by my words,” say, “I’m sorry I said hurtful things.” The second most important element, the research found, is to offer a repair or make amends.

While the transgressor might not necessarily be able to undo the damage, there are usually steps you can take to reduce the harm. And the least effective part of an apology? Asking the offended person wronged “do you forgive me?”

Apologizing is not just for the victim, but also for the perpetrator, argue Jonathan Cohen and David De Cremer published their study on apologies which found that people often overestimate the extent that an apology will make them feel better. He argues that the factors which seem to have the biggest impact in the apology are acknowledging personal responsibility, an explanation for why the violation occurred and an offer of repair or amends.

Aaron Lazare, in his book, On Apology, argues that apologizing too soon may be counterproductive, and misses a step in reconciliation. This perspective is reflected in the arguments of Frank Partnoy, author of Wait: The Art and Science of Delay, argues we have to resist the impulse to react to everything immediately, which doesn’t allow some time for the injured party to vent or deal with their emotions.

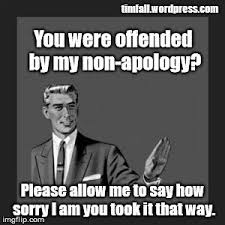

The Non-Apology

On a daily basis now, we see politicians from the White House down to the local level, not just refusing to apologize and take responsibility but giving non-apologies—the appearance of an

apology.

Editors at Oxford Dictionaries recently added an entry for “non-apology,” defining it as a statement that takes the form of an apology but doesn’t sufficiently acknowledge responsibility or regret. Oxford also added an entry for “apology tour,” a series of public appearances by a well-known figure to express regret over a wrongdoing.

“I want to apologize is not an apology.” It’s no more an apology than “I want to lose weight” is a loss of weight. “I’m sorry if you were offended,” or “I’m sorry I hurt your feelings” are not apologies. These imply that the inured party may be too sensitive, and the problem is their perception of what happened. “I’ve really been upset over what I did,” or “I’m losing sleep over this,” are not apologies. They put the focus on the transgressor’s well being and ask the offended party to show compassion and caring for the transgressor. “Everybody makes mistakes, and I’m not perfect,” is not an apology. It avoids personal responsibility by projecting the responsibility onto others. “I hope you won’t hold this against me,” is not an apology. It’s passive aggressive at best and aggressive at the worst because it implies some retribution or punishment of the injured party. For example, someone says “I called you an idiot but I’ve been under a lot of stress/have too much going on.” This is not an apology but a rationalization or excuse. The give away is often the word “but.”

The non-apology often puts the blame on the critics of the perpetrator, because the message is “If anyone is stupid or too insensitive to be offended by what I did, then I guess I apologize, but only because their unreasonableness forces me to do so to make the problem go away.” This illustrates a lack of empathy, insincerity and a refusal to accept personal responsibility for their own acts. Language is also manipulated in a non-apology to give the appearance of an apology.

Here are some examples:

- When apologies are offered in public life, they tend to be the sort that subtly shifts the blame: “I apologize if anyone was offended.” This is, of course, another way of saying, “I’m sorry you are so sensitive.” No one was ever mollified by such an apology, but some how it remains in use.

- Using the passive-voice: “mistakes were made” has become a parody of the political non-apology, often using the conditional—an “if” clause. This short-circuits the apology process by placing the onus on the offended party to confirm that an offense actually took place.

- Closely related to the conditional apology is the reliance on indefinite pronouns such as “anyone” and “anything” to avoid naming the offence. Carried to the extreme, reliance on indefinites ends up like this: “I’m apologizing for the conduct that it was alleged that I did, and I say I am sorry.”

- Politicians who blame “a poor choice of words” or say they “regret that my words were misinterpreted,” or the ever popular, “I misspoke.”

Forgiveness

Forgiveness is a power held by the victimized, not a right to be claimed. The ability to dispense, but also to withhold, forgiveness is an ennobling capacity and part of the dignity to be reclaimed by those who survive the wrongdoing. Even an individual survivor who chooses to forgive cannot, properly, forgive in the name of other victims. To expect survivors to forgive is to heap yet another burden on them.

Analysts of interpersonal apologies frequently address the question of forgiveness and the conditions under which recipients are willing or unwilling to forgive apologizers for their transgressions. The definition of forgiveness varies: for some analysts, mere acceptance of an apology implies forgiveness, while for others, forgiveness is a deep psychological process in which the recipient of the apology relinquishes his anger or desire for vengeance,

“surrendering the right to get even,” and is able to focus on other matters, thus “moving on” (to resort to popular parlance).

Forgiving does not mean excusing, condoning, ceasing to blame, losing respect for the victims, or forgetting that wrong-doing occurred. What happens in forgiving is that we relinquish our feeling of hatred and resentment and accept that the wrongdoer has repented and reformed.

Summary:

Each of us can ensure we embrace the significance of apologies in maintaining social cohesion. And above all, ensure they are true apologies, containing the elements described in

this article.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.