By Ray Williams

June 4, 2020

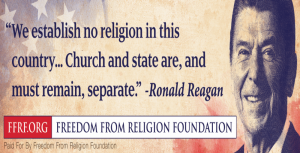

The U.S. Constitution does not mention the Bible, God, Jesus or Christianity, and the First Amendment clarifies that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” Still, some scholars have argued that the Bible heavily influenced America’s founders.

There is compelling research that shows that religion has had and continues to have a significant influence on social and economic conditions and politics in America, in stark contrast to other developed western countries.

Today, about half of Americans (49%) say the Bible should have at least “some” influence on U.S. laws, including nearly a quarter (23%) who say it should have “a great deal” of influence, according to a 2020 Pew Research Center survey. Among U.S. Christians, two-thirds (68%) want the Bible to influence U.S. laws, and among white evangelical Protestants, this figure rises to about nine-in-ten (89%).

In contrast, the Pew Survey reports, there’s broad opposition to biblical influence on U.S. laws among religiously unaffiliated Americans, also known as religious “nones,” who identify as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.” Roughly three-quarters in this group (78%) say the Bible should hold little to no sway, including 86% of self-described atheists who say the Bible should not influence U.S. legislation at all. Two-thirds of U.S. Jews, as well, think the Bible should have not much or should have no influence on laws.

The Pew Survey reports that older Americans are much more likely than younger adults to want biblical influence on U.S. laws, while Republicans – by a two-to-one margin – are more likely than Democrats to do so.

All survey respondents who said the Bible should have at least “some” influence on U.S. laws were asked a follow-up question: When the Bible and the will of the people conflict, which should have more influence on U.S. laws?

The more common answer to this question, which should raise the eyebrows of many people, is that the Bible should take priority over the will of the people. This view is expressed by more than a quarter of all Americans (28%). About one-in-five (19%) say the Bible should have at least some influence but that the will of the people should prevail.

According to the Pew Survey, two-thirds of white evangelical Protestants (68%) say the Bible should take precedence over the people, and half of black Protestants say the same. Among Catholics (25%) and white Protestants who do not identify as born-again or evangelical (27%), only about a quarter share this perspective.

Recent other surveys by the Pew Center find that most white evangelical Protestants (63%) and half of black Protestants (50%) continue to opposelegal same-sex marriage.

Religion in the United Statesis remarkable in its high adherence level compared to other developed countries. A majority of Americans report that religion plays a “very important” role in their lives, a proportion unusual among developed nations.

Historically in America, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the two major parties polarized along ethnic and religious grounds. In the North, most Protestants were Whigs or Republicans; most Catholics were Democrats. In the South, from the 1860s to the 1980s, most whites were Democrats (after 1865) and most blacks were Republicans.

According to the American Religious Identification Survey, religious belief varies considerably across the country: 59% of Americans living in Western states report a belief in God, yet in the South (the “Bible Belt”) the figure is as high as 86%.

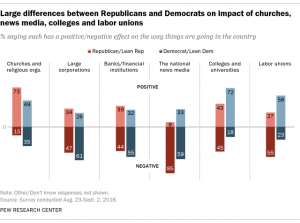

There are Christiansin both the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, but evangelical Christianstend to support the Republican Party whereas more liberal Christians, Catholics and secular voters tend to support the Democratic Party. A 2019 survey conducted by Pew Research Center found that 54% of adults believe the Republican Party to be “friendly” toward religion, while only 19% of respondents said the same of the Democratic Party.

Every President and Vice President, was raised in a family with affiliations with Christian religions.Only former President John F. Kennedy, and former Vice President Joe Bidenwere raised in Roman Catholicfamilies. Two former presidents, Richard Nixonand Herbert Hoover, were raised as Quakers. All the rest were raised in families affiliated with ProtestantChristianity. However, many presidents have themselves had only a nominal affiliation with churches, and some never joined any church.

Religious lines in America have been sharply drawn.Methodists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, Scandinavian Lutherans and other pietistsin the North were tightly linked to the Republicans. In sharp contrast, liturgicalgroups, especially the Catholics, Episcopalians, and German Lutherans, looked to the Democratic Party for protection from pietistic moralism, especially prohibition. While both parties cut across economic class structures, the Democrats were supported more heavily by its lower tiers.

Cultural issues, especially prohibition and foreign language schools, became important because of the sharp religious divisions in the electorate. In the North, about 50% of the voters were pietistic Protestants who believed the government should be used to reduce social sins, such as drinking. Liturgical churches constituted over a quarter of the vote and wanted the government to stay out of personal morality issues. Prohibition debates and referendums heated up politics in most states over a period of decades, and national prohibition was finally passed in 1918 (repealed in 1932), serving as a major issue between the wet Democrats and the dry Republicans.

Religion is important for American politics because religion is important for Americans. Yet, there are factors in American political life that amplify the role of religion in a way that is not seen in other developed countries.

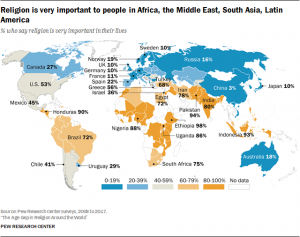

For a developed country, the U.S. is extraordinarily high on religion. According to one study, 65 percent of Americans say that religion is important in their daily lives compared to just 17 percent of Swedes, 19 percent of Danes, and 24 percent of Japanese.

Why America is more religious than Europe

There are several likely reasons why Americans say that they are so much more religious than Europeans. One may be that they exaggerate their own religiosity in the same way that they claim about twice the attendance rates relative to people actually showing up in church.

There is also a large immigrant population, many of whom hail from countries that are poor and comparatively religious. Immigrant groups that happen to be linguistically isolated may remain quite religious even if the broader society becomes increasingly secular.

Life is more difficult in the U.S. than in Europe by several measures even though Europe is currently in an economic decline.Problems here range from health problems and lower life expectancy, to higher crime rates, and relative lack of involvement in the community. All of these problems are bound up with inequality – with a chasm between the living conditions of rich and poor.This gap has widened in recent decades and reveals holes in social safety nets relative to Europe.

In comparison with European nations (and in Canada, Australia and New Zealand), Americans feel far less secure economically, and in relation to their health and well-being compared to wealth of the country in terms of GDP per capita. This existential insecurity provides a fertile ground for religion. Many experts now question the relevance and accuracy of GDP as a measure of true economic well being.

Why religion is emphasized in American politics

Religion influences American politics to a degree not seen in other developed countries. Despite the constitutional firewall between church and state, national politicians hardly ever give a major speech without invoking religion.

The president is forever asking God to bless America, sending his prayers to victims of disasters, hosting religious leaders, and extolling religious values. Such advocacy of religion is unheard of in Europe but that may be because the majority is no longer religious and because voting members of the native population (as distinct from immigrants) are not very devout.

In America, religion is much more a part of public life whatever the constitution says. There are various reasons for this. One is that evangelical Christians under the banner of the Moral Majority made a determined push to influence political leaders since the 1970s and to inject religion into political debates. This broad agenda animates contemporary right-wing media including talk radio personalities such as Rush Limbaugh and TV channels such as Fox News.

The religious propensities of immigrants mean that they are receptive to the conservative religious message and can be induced to vote across class lines. In doing so they support an agenda that favors the wealthy and makes them even poorer.

Given this threat from the religious right, Democrats feel pressure to emphasize their own religious credentials, or risk losing a chunk of the poorer immigrant population who make up their natural constituency.

So religion is embroiled in American political life and that magnifies the apparent significance of religion in people’s everyday lives. According to some experts, U.S. conservatives went to war in Afghanistan to separate religion from politics abroad while striving to unite religion and politics at home.

That religious propensity is strengthened by increasing insecurity in the lives of the poor because difficult living conditions are associated with increased religiosity. So the worse their living conditions become, the more likely they are to follow a self-defeating voting pattern. That seems like another great reason for really separating church and state.

In 2017 an evangelical perspective influenced many political decisions, as President Donald Trump embraced the key constituency that voted overwhelmingly in his favor. As recently as Dec. 6, President Trump announced that the U.S. would recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, a move embraced by many evangelicals, for its significance to a biblical prophecy.

Earlier in the year Trump made several other announcements keeping in mind his conservative Christian supporters. He nominated Judge Neil M. Gorsuch, a conservative judge, to the Supreme Court. He also brought evangelical Christian leader Jerry Falwell Jr. to head the White House education reform task force, and Betsy DeVos, a conservative advocate of school choice, to serve as secretary of education.

Trump’s move of Jerusalem was widely understood as being linked to a biblical prophecy. Many evangelical Christians believe in an end-times narrative that promises the return of Jesus to the Earth to defeat all God’s enemies and establish God’s kingdom. The nation of Israel and the city of Jerusalem are crucial for the fulfillment of this prophecy. This is part of a theology considered to be a literal reading of the Bible.

Evangelicals have for decades played a prominent role in American politics. As the senior director of research and evaluation at the University of California, Richard Flory wrote, President Trump’s appointing Jerry Falwell Jr. to spearhead education reform is best explained by his family’s legacy.

Falwell founded the Moral Majority in 1979 as a conservative Christian political lobbying group that promoted “traditional” family values and prayer in schools and opposed LGBT rights, the Equal Rights Amendment and abortion – all key issues in Trump administration as well.

“Republican candidates for office, dating back to Reagan and George H.W. Bush,” Flory says, recognized the power of the religious right as a voting bloc.“

Before Falwell, it was evangelist Billy Graham who left a deep impact on conservative politics.

The National Prayer Breakfast, now an annual political tradition in Washington D.C., and attended by the American president, was a result of Billy Graham’s efforts with President Dwight Eisenhower.

As University of California religion scholar Diane Winston writes,“Soon after his election in 1952, Eisenhower told Graham that the country needed a spiritual renewal. For Eisenhower, faith, patriotism and free enterprise were the fundamentals of a strong nation. But of the three, faith came first.” It was, indeed, under Eisenhower that Congress voted to add “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance, and “In God We Trust,” to the nation’s currency.

Besides these prominent individual conservative voices, there are other Christian groups trying to shape American politics and the religious landscape. Both Winston and Flory pointed in particular to the Moral Majority as a fast-growing Christian movement that aims to bring God’s perfect society to Earth by placing “kingdom-minded people” in “powerful positions at the top of all sectors of society.”

Writing about this movement, Brad Christerson, professor of sociology at Biola University together with USC’s Richard Flory, explainhow this movement regards Trump as part of that plan. Other kingdom-minded people include Secretary of Energy Rick Perry, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos and Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson.

Christerson and Flory believe the Moral Majority with it’s belief in the kingdom of heaven to be the fastest-growing Christian group in America and possibly in the world. Between 1970 and 2010, Protestant churches shrunk by an average of .05 percent per year but this group grew by an average of 3.24 percent per year. This number, they say, was “striking,” when considering the fact that U.S. population grew an average of 1 percent per year during this time period.

Economic Inequality

The New York Times recently reported on a new study by economists from Harvard and UC Berkeley on income mobility across the country. The research team found stark differences by geographical region, with the odds of moving to a different income bracket being lowest in the southeast and higher in major metropolitan areas. They identified four broad factors in areas that contribute to income mobility: mixed-income neighborhoods, two-parent households, better schools, and higher rates of civic engagement, “including membership in religious and community groups.”

Why religion asks Julie J. Park, assistant professor of education at the University of Maryland, College Park and author of When Diversity Drops: Race, Religion, and Affirmative Action in Higher Education?

There are numerous reasons, Park says, but emphasizes one: Religious communities as a source of social capital. As Robert Putnam addressed in Bowling Alone,religious institutions such as churches, synagogues, and mosques bring people together in a way that strengthens community life. This is vital in a society that is increasingly fragmented. This connectedness likely affects income mobility via social capital — the relationships and relational networks that lend themselves to the exchange of knowledge and resources. For instance, in a religious community, people might form relationships that lead to helpful information about finding a job, navigating social services, or starting a business. Rich relational networks also have payoffs for education, which has natural dividends for income mobility. Being involved in a religious community gives kids the opportunity to have multiple adults in their lives who are invested in their well-being, as documented by sociologist James Coleman and others. These overlapping social relationships (e.g., knowing an adult from the neighborhood, and also attending mosque with them) can reinforce social norms that are beneficial for educational outcomes.

Another perk is that social capital networks can help people access valuable information that helps them navigate the educational system, Parks says, which has particular dividends for low-income students. In a study of first-year college students, Korean American low-income youth had a particularly high rate of taking SAT preparatory classes. Taking SAT prep was higher for Korean Americans who identified as Protestant, suggested that these students are able to access information about applying to college through social networks in economically diverse immigrant churches.

Such social connections can potentially happen in any type of civic organization (the Harvard/Berkeley study highlights the role of membership in non-religious community groups), but religious institutions tend to be relatively enduring. They often provide a joint social service function, especially among immigrant populations, and can provide rhetorical frameworks that help people endure through difficult times.

Given all of the benefits of religious involvement, Park asks, why is income mobility lowest in the South, given its high religiosity? As a social scientist, she says she is curious to know whether there is something different about religion in the South, or is it that the other elements that boost income mobility (two parent households, mixed-income neighborhoods, good schools) are somehow lagging in the South? Or is it some combination of all of the above? One hypothesis might be that Southerners are more likely to worship in megachurches, which might be less likely to foster the social relationships and networks that contribute to income mobility. A map of megachurches in the U.S. provides some evidence that there are more megachurches in the South.

Another theory by researchers is that White evangelical and fundamentalist Christians, a prominent Southern demographic, tend to support individualist explanations and solutions for inequality. This trend is documented by Michael Emerson and Christian Smith in their book Divided by Faith. By individualist, think “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” versus questioning whether there are bootstraps there to begin with. This tendency may lead to diminished support for government spending — not just federal, but also state and local — on schools and other policy initiatives that could enhance income mobility. Read David Swartz’s The Moral Minorityfor a fascinating read on the political diversity of evangelicals.

Overall the causes for low income mobility in the South and elsewhere are difficult to isolate because they are most likely interconnected: In the South, high religiosity likely has some positive dividends for income mobility, but the effects may be blunted by other ramifications of religious practice and belief. Naturally there is diversity both within and between religious traditions. There is no neat and tidy answer for the pervasiveness of income inequality, but understanding how religion affects people’s beliefs about the solutions needed to strengthen families, schools, and neighborhoods is a critical part of the puzzle.

How Religion Contributes to Inequality

Wealth ownership is highly concentrated in the United States. The top 1 percent of households have consistently owned about 33 percent of net worth, and wealth inequality has escalated since the recession and COVID-19. High levels of wealth provide great advantage, but even a small amount of savings can mitigate the effect of financial shock. Wealth inequality is relatively enduring within and across generations and can have significant educational, occupation, political and social advantages. Wealth provides a buffer against financial emergencies and can generate more wealth when it is reinvested.

Researchers are only beginning to understand the complex individual and family processes that affect saving and wealth ownership, but religion has emerged as an important part of the process. Religion embodies a great deal about a person’s general approach to the world—their conception about how the world does and should work—and we are learning that it can shape financial outcomes in surprising ways.

There are two broad reasons that religion and wealth are related. First, religion affects wealth indirectly through its very strong effect on important processes such as educational attainment, marriage, decisions to have kids, how many kids people have and women’s decisions to work or stay home with their kids. Religion affects these behaviors and processes, and they, in turn, affect household income, expenses and the amount of money left over to save. Understanding these processes alone accounts for a large portion of the religion-wealth association.

Second, religion can also affect wealth directly by influencing intergenerational processes, social relations and orientations toward work and money. Intergenerational processes (the transfer of both religious ideas and wealth from parents to children) and social relations (contacts made through religious group who can provide information, capital and other resources) are certainly important.

One of the most fascinating explanations is the direct effect religion can have on orientations toward work and money. Many of the important decisions about family, work and saving have roots in their religious beliefs. For example, in some conservative religious groups—including Conservative and Black Protestant denominations—becoming a minister, working for a social service agency or becoming a career missionary are considered good jobs. A calling into one of these careers can be important for religious reasons, but these jobs don’t necessarily require high levels of education, don’t typically pay well and won’t make it easy to save and accumulate wealth.

Some examples can help illustrate these processes. Results from analyses of the National Longitudinal Survey, the Health and Retirement Study and the Economic Values Survey suggest that Conservative Protestant and Jewish families tend to be polar opposites on most measures of wealth. The results also show that behaviors regarding family, education, work and saving help explain why. Conservative Protestants often favor large families and a traditional gender division of labor in which women do not work out of the home. Conservative Protestants have also had, on average, lower levels of education than other groups. Having a large family, low education levels for parents and a single income-earner both make saving difficult and can lead to low wealth. Many Conservative Protestants also view money as belonging to God. People are considered managers of the money but should consult God or God’s agents on earth regarding decisions to use their money. Tithing as a percent of income tends to be high in these faiths, and the desire to accumulate excess assets in-person bank accounts can be seen as undesirable. As this suggests, Conservative Protestants have been at the low end of the wealth accumulation.

At the opposite end are Jewish families. Many Jewish mothers also stay home with their children for at least the first years of the child’s life. But Jewish mothers are more likely to have high levels of education and a relatively small number of children. This makes it easier for the Jewish mother to devote time and other resources to early education. The Jewish mother is also more likely to return to work after her children enter school, adding to income and making saving and wealth accumulation more possible. Jewish families are also more likely to take a pragmatic approach to money—that is, money is more likely to be seen as a tool or a vehicle for taking care of family needs and other practical concerns—and tend to accumulate relatively high amounts of wealth.

White Catholics are an important example because their position in the wealth distribution has changed considerably in recent years. Less than a generation ago, white Catholics were relatively disadvantaged: they had low educations, low income, low wealth. Important shifts in orientations toward family and women’s roles in the family were important contributors. White Catholics now have much smaller families than in prior generations and Catholic women are as likely as Mainline (or Liberal) Protestants to work out of the home. Combined with a pragmatic, pro-saving orientation toward work, this has propelled white Catholics up in the wealth distribution in recent years.

Mormons (LDS) are also interesting because they combine elements of groups that are otherwise distinct. Mormons tend to be religiously conservative, favoring large families and traditional gender roles. However, Mormons typically have high educations and report more pragmatic orientations toward money and accumulation. The result appears to be that Mormons have higher wealth than other conservative Protestant groups, although these findings are a bit more speculative than for other groups because Mormons make up a relatively small proportion of the U.S. population.

Naturally, these relationships and processes are much more nuanced than simple examples suggest; there are very important differences within each of the groups I mention and a large number of other factors affect wealth accumulation as well. These examples also leave open questions about happiness: wealth does not necessarily lead to greater satisfaction, and some argue that investing in religion can have both intangible and tangible benefits. However, it has become clear that the relationship between religion and wealth is very strong. The recent recession underscored the need for savings at all levels of wealth, and the importance of religion in American culture suggests that this may be an important part of the explanation for growing inequality.

In a published study, “Religion, Income Inequality, and the Size of the Government,” Ceyhun Elgin, and colleagues show that countries with higher levels of religiosity are characterized by greater income inequality. They argue this is due to the lower level of government services demanded in more religious countries. Religion requires that individuals make financial sacrifices and this leads the religious to prefer making their contributions voluntarily rather than through mandatory means. To the extent that citizen preferences are reflected in policy outcomes, religiosity results in lower taxes, which in turn implies lower levels of spending on both public goods and redistribution. Since measures of income typically do not fully take into account the part of income coming from donations received, this increases measured income inequality.

America is the most religious wealthy country in the world, according to a recent survey. A Pew survey found that Americans said they prayed more than any other wealthy nation surveyed.

Fifty-five percent of Americans report praying at least once daily, 6 percentage points higher than the international average. While this may not seem like a big gap on its own, America is an extreme statistical outlier when it comes to countries with at least a $30,000 per person GDP. In this category, the global average hovers around 40 percent. In Canada, for example, only 25 percent of people pray daily. That number drops to 22 percent in Europe (on average), 18 percent in Australia, and a minuscule 6 percent in Great Britain.

In fact, the study’s authors found, America was the onlycountry out of the 102 surveyed to score higher-than-average on metrics of both religiosity, or the reported frequency of prayer, as well as national wealth, as measured in GDP per capita. By contrast, countries that report daily prayer rates comparable to the United States tend to be poorer, such as Bolivia (56 percent) and Bangladesh (57 percent).

Three years ago, Pew conducted a similar study, in which a comparable percentage of Americans (53 percent) reported that religion was “very important” in their lives. In that study, too, a given country’s answers seemed to track with that country’s wealth. Ethiopia (98 percent), Senegal (97 percent), and Indonesia (95 percent) had the highest percentage of respondents affirming the extreme importance of religion in their lives, while France (14 percent), Japan (11 percent), and China (3 percent) had the lowest.

The idea that a country’s religiosity and its GDP inversely correlate is not a new one. A 2009 Gallup poll, for example, found that among countries with a GDP of less than $2,000 per capita, the median percentage of those who saw religion as important in their lives was 95 percent. When a country’s GDP was above $25,000, that median percentage dropped to 47 percent.

Why? In 2004, sociologists Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart came up with the term “religiosity gap” to describe the phenomenon. In their book Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide, they posited that in societies where individuals are more vulnerable, in part as a result of poverty, religion is a stronger force for social and emotional cohesion.

In richer and more stable societies, by contrast, religion became a less necessary force. At the same time, it seems that the reverse is often true: Secularization is frequently a harbinger of economic growth. A study published in Science Advances earlier this year found that increased secularization of a country predicted economic growth, rather than the other way around.

So what makes the United States such an outlier? Pew’s Dalia Fahmy suggests that a useful predictor of religiosity was not simply wealth but wealth inequality.When the Pew data about religiosity is tracked against a country’s relative wealth equality or inequality, rather than GDP, the United States’ religious observance is no longer statistically anomalous. Withinthe US, states with the greatest income inequality are also those with the highest levels of religious observance.

Summary:

Religion has had a significant influence on social and economic equality and politics in America, despite the provisions in its constitution and laws. And in contrast to other Western countries, especially European, the percentage of people who identify themselves as religious is much higher in America. Research evidence also shows that income inequality—which is the highest in America of all developed countries—is correlated with levels of religious beliefs and practice. And finally, the influence of religious groups on politics and the affiliation with the Republican party in particular, in America has been significant factor, especially in recent times.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.