By Ray Williams

February 15, 2021

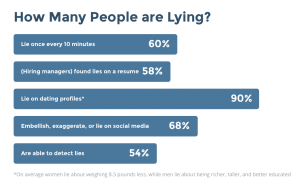

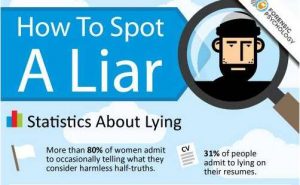

Lying and deception are common human behaviors. Until relatively recently, there has been little actual research into just how often people lie. A 2004 Reader’s Digest poll found that as many as 96% of people admit to lying at least sometimes.

One national study published in 2009 surveyed 1,000 U.S. adults and found that 60% of respondents claimed that they did not lie at all. Instead, the researchers found that about half of all lies were told by just 5% of all the subjects. The study suggests that while prevalence rates may vary, there likely exists a small group of very prolific liars.

The reality is that most people will probably lie from time to time. Some of these lies are little white lies intended to protect someone else’s feelings (“No, that shirt does not make you look fat!”). In other cases, these lies can be much more serious (like lying on a resume) or even sinister (covering up a crime).

The average person hears between 10 and 200 lies per day. Strangers lie to each other three times within the first 10 minutes of meeting, on average. College students lie to their mothers in one-fifth of all interactions.

According to Pamela Meyer, author of the book Liespotting and presenter of a TED Talk with more than 16 million views, the answer is: They’re all true. So if we’re being lied to that often, how can we do a better job of catching the prevaricators we interact with?

Lying Can Be Hard to Detect

People are surprisingly bad at detecting lies. One study, for example, found that people were only able to accurately detect lying 54% of the time in a lab setting—hardly impressive when factoring in a 50% detection rate by pure chance alone.

Clearly, behavioral differences between honest and lying individuals are difficult to discriminate and measure. Researchers have attempted to uncover different ways of detecting lies. While there may not be a simple, tell-tale sign that someone is dishonest (like Pinocchio’s nose), researchers have found a few helpful indicators.

Like many things, though, detecting a lie often comes down to one thing—trusting your instincts. By knowing what signs might accurately detect a lie and learning how to heed your own gut reactions, you may be able to become better at spotting falsehoods.

Psychologists have utilized research on body language and deception to help members of law enforcement distinguish between the truth and lies. Researchers at UCLA conducted studies on the subject in addition to analyzing 60 studies on deception in order to develop recommendations and training for law enforcement. The results of their research were published in the American Journal of Forensic Psychiatry.

Research by Dr. Leanne ten Brinke, a forensic psychologist at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, and her collaborators, suggests that our instincts for judging liars are actually fairly strong — but our conscious minds sometimes fail us.

Dr. Lillian Glass, behavioral analyst, body language expert, and “The Body Language of Liars” author, said when trying to fgure out if someone is lying, you Krst need to understand how the person normally acts. Certain habits, like pointing or over-sharing, might be perfectly within character for an individual.

Former CIA officers Philip Houston, Michael Floyd, and Susan Carnicero distilled their professional deception-detecting skills into a fascinating book, Spy the Lie, also reveal how to tell if someone is lying.

Guidance from Investigators

All behavior—facial expressions, voice tone, posture, gaze, and proximity—can communicate important information. However, when assessing the accuracy of a subject’s demeanor, investigators often are plagued by deception myths, particularly the relationship between nonverbal behavior and deceit.

One of the most common misconceptions is the belief in universal signs of deception—consistent, reliable indicators that a person is lying. There are some signs that appear more frequently among liars than truth tellers; however, there has been no universal sign of lying identified. This is because not all liars demonstrate the same behaviors. One liar may decrease eye contact, while a second person may increase eye contact in response to the same question. This is complicated by the fact that the same person can respond differently in the same situation—interpersonal differences—and also in different contexts—intrapersonal differences.

It is likely that anyone who interviews criminals for a living will be lied to on a regular basis. In a study involving 509 people from a variety of career fields and agencies, only the U.S. Secret Service agents performed better than chance (50 percent). A number of other studies have provided similar results.

Another myth is the belief that only guilty people appear nervous. This idea assumes that a person who has nothing to hide has no reason to be nervous or to demonstrate fidgeting and anxiety often associated with deceit. Questioning by law enforcement can be stressful for anyone, especially someone with little understanding of the criminal justice system. That anxiety can be heightened by accusatory questions or an aggressive interviewing style. Not surprisingly, innocent individuals often demonstrate many of the stereotypical behaviors associated with deception, including speech errors, fidgeting, and gaze aversion.

Deception

Lie detection is a difficult task, and some techniques work part of the time and only with some people. No single technique is effective all of the time under all conditions. There is no approach or question that enables you to separate lying from truthfulness in every situation. In fact, some methods may decrease the accuracy.

Deception is a fact of life that people seldom think about. There are two primary ways that people lie—concealment and falsification. Concealment occurs when a person evades the question or omits relevant details. Liars often prefer this because it can be difficult to reveal. Without evidence it can be challenging or nearly impossible to validate the truth or falsity of a person’s statement. Concealment is easier than falsification because the liar does not have to remember what was said previously, and it provides numerous built-in excuses. For example, the liar can claim ignorance or a faulty memory.

Concealment often is all that is necessary to mislead another person; however, there are times when falsification is necessary. For example, lying about one’s whereabouts during the time a crime was committed cannot be accomplished by concealment alone. The subject must fabricate a story.

Regardless of the type of lie, the goal is the same—to intentionally mislead another person into believing something the liar knows is false. People who unknowingly provide false information do not demonstrate emotional arousal or other cues associated with deception. It is only when a lie is told knowingly and intentionally that the liar can be expected to display signs.

Lie Detection

Despite the inherent difficulties of detecting a lie, social scientists are beginning to better understand the psychological, emotional, and behavioral cues associated with deceit. To date three approaches have demonstrated the most promise: 1) emotional, 2) cognitive, and 3) attempted control.

Emotional Approach

Lies fail because of the difficulty concealing or falsifying emotions around others. Strong feelings and many of the behaviors they produce are beyond conscious control. Not all lies involve emotions, but those that do often present special problems for the liar.

People do not choose the type of emotion they will experience, when they will feel it, or how intense it will be. Sometimes it is possible for a person to dampen a response; however, it is almost impossible to eliminate all evidence of feelings. This is especially true when the stakes are high, as they often are during an investigative interview.

Strong emotional responses activate the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which, in turn, produces physiological, behavioral, and cognitive changes.

Physiologically the release of adrenaline and glucocorticoids causes increased blood pressure, heart rate, respiration, and body temperature. Thus, a person facing a threat often exhibits flushing or blanching, perspiration, and nervous energy. Strong negative emotional responses may cause behavioral withdrawal—gaze aversion, decreased body orientation, and diminished illustrators. These changes accompany physical (imminent assault) and psychological (loss of self) threats.

Most liars only demonstrate signs of emotion, ANS activation, and other deceit-associated cues when the stakes are high. Emotional activation is strongest when the liar has something to gain or lose. When the stakes are low, there is little chance the subject will demonstrate any of the cues being discussed. Most investigative interviews involve high stakes and potentially negative consequences; however, subjects with high levels of confidence in their ability to lie or those who feel they have little to gain or lose may be difficult to identify.

Emotional cues fall into two broad categories—lying about feelings and feelings about lying. In the first instance, people lie about what they are feeling. For example, criminals who are fearful may laugh or cover their faces to hide true feelings. In the second case, lying often generates strong feelings of guilt, anxiety, or fear that are separate from actual guilt or innocence. A person who lies but recognizes that deceit is ethically wrong may feel guilty, or the individual might experience excitement at the thought of fooling the other person. In either case, the person must conceal those feelings.

There are three emotions closely associated with deceit: 1) fear, 2) guilt, and 3) delight. Fear is a reaction to the threat of physical or psychological harm brought on by high-stakes lies. The body’s response is to produce physiological changes—muscle tension and increased body temperature, respiration, and heartbeat. The level of fear depends on the person’s belief in their lying skills and the stakes involved. Some people are naturally gifted liars who have learned from experience that it is easy to fool others. They rarely are detected, and they have a high degree of confidence in their ability to deceive.

Deception guilt refers to a person’s feelings about lying, not whether someone is guilty or innocent. It is different from feeling guilty about the content of a lie. A person does not have to feel guilty about the lie itself to feel guilty about the act of lying. The amount of deception guilt that people experience varies, but strong feelings of guilt or shame sometimes are enough to produce a confession. Some people are more susceptible to deception guilt, such as those raised in a home with strict beliefs about dishonesty, particularly where lying was characterized as a sin.

Excitement, or “duping delight,” is the positive feeling a liar experiences when anticipating the challenge of a lie or during the moment of lying when one’s success has yet to be assured. A person experiencing duping delight can display a number of emotions—contempt, enjoyment, or excitement. It is common for criminals to confess their crimes to friends or strangers and, in some cases, to investigators to receive acknowledgement for their ingenuity and intelligence.

Emotional expressions sometimes provide clues to what a person is feeling; however, they do not reveal the source of the feelings. For example, a person who is confronted regarding a spouse’s murder may express signs of fear and guilt when asked for whereabouts during the crime. Although the subject is innocent, a display of strong emotion may occur because the individual was carrying on an extramarital affair at the time of the murder. The expressions of fear about being discovered and guilt concerning the actions are real but unrelated to the crime.

Because feelings do not reveal their sources, they must be considered in the context in which they occur. People differ in their expressiveness and ability to conceal emotions. It is only when the expression does not match the spoken word that attention should be paid to the details of the person’s story. Open-ended questions, can help you attend closely to the subject’s responses, monitor emotional triggers, and compare the person’s answers with the facts.

Cognitive Approach

A second reason that lies fail is the mental effort required to create and communicate a plausible story. Lying persuasively is hard for many people, especially those who are unprepared. Although, even when a liar is prepared, it may be difficult to lie convincingly. The liar must construct a story consistent with what the interviewer knows or may discover, keep track of everything being said, anticipate future questions, and avoid providing too much information. The effort required to lie varies among people; however, evidence suggests that liars are more likely than truth tellers to exhibit certain behaviors—hesitating, making errors, speaking slower, pausing more, and waiting longer before answering.

A study of 99 police officers who viewed fragments of 54 videotaped interviews with murderers, rapists, and arsonists indicated that officers who relied on verbal cues (e.g., vague responses or contradictions) distinguished between truth and deception better than those who depended on more visual signs (e.g., gaze aversion or postural shifts). Researchers found an opposite relationship between nonverbal behaviors (e.g., fidgeting and looking away) and accuracy. The police officers who specifically mentioned that liars looked away and fidgeted obtained the lowest scores, while those who paid attention to verbal responses were more accurate in their judgments.

The cognitive approach to deception is based on the idea that lying requires more mental resources than truth telling. The increase in mental load required to formulate and communicate a plausible story, monitor body language and emotional expressions, and anticipate future questions is believed to make liars vulnerable to additional questions they failed to anticipate. Investigators can take advantage of this by focusing on non-accusatory, open-ended questions designed to elicit narrative responses.

Studies have suggested that investigators who have to deal with a liar rely on two interviewing styles—information gathering and accusatory. An investigator using the information-gathering style asks open-ended questions (e.g., “In your own words, tell me what happened”) that require the interviewee to provide detailed statements. With an accusatory style, the interviewer uses allegations (e.g., “Obviously you are hiding something”) in the hope of obtaining an admission or confession. The purpose of each interview and the quality and quantity of information obtained are different. Interviews are for gathering facts, and the more detailed and complete the information, the more successful the interview.

The more information an investigator can secure, the more chances exist to compare those facts with available evidence. The longer the interview, the more opportunities to examine the interviewee’s responses. Focusing on information-gathering interviews because they do not accuse the subject of any wrongdoing are less likely to result in false confessions.

Attempted Control Approach

The third reason lies fail is the unnatural appearance of liars who attempt to control their behavior, known as using countermeasures. Liars know that observers pay close attention to behavior, so they manage their nonverbal behaviors to make themselves appear honest and sincere. These individuals often are mindful of stereotypical behaviors—gaze aversion, fidgeting, and postural shifts—commonly associated with deception. They sometimes go to great lengths to maintain eye contact, control gestures, and present an emotionally cool demeanor.

Despite a liar’s best efforts, it is impossible to monitor, control, or disguise all behavior. Some behaviors, such as the physiological changes that accompany strong emotions, are beyond conscious control. This is further complicated because people usually are unaware of their own behavior and how they appear to others, so subtle changes in their demeanor may leak valuable information.

One strategy liars use to limit the amount of untruthful information is to embed the lie in a number of truths. Instead of telling a complex, blatant lie, the person inserts untruths into an otherwise truthful account. For instance, robbery suspects who want to conceal their whereabouts on the evening of a crime may provide details of activities that occurred the night before the incident, significantly reducing the amount of untruthful information they must remember. They only change the date of the activities, not the activities themselves. Individuals who embed lies in otherwise truthful accounts and who monitor their behaviors often are difficult to spot.

Baseline Calibration

People’s speech and behavior vary. Some individuals make several movements, some are articulate and persuasive, while others demonstrate major differences in their physiological responses. Rather than assessing responses as they occur during an interview, investigators who have to deal with liars first should determine how the subject looks and sounds when communicating truthfully. Then they should watch for behaviors that deviate from that normal style or baseline.

When comparing verbal and nonverbal behaviors with the baseline, the investigator must ensure the person’s responses are from the same interview setting, about similar topics, and from interviews that occurred within a short time period. This is important because conversations are low-stakes situations where it is unlikely that the person’s responses will result in negative consequences. In contrast, interviews to discuss the elements of a crime are high-stakes situations that could bring about grave penalties.

There is no universal sign of deception. Good investigators avoid focusing on any one behavior and look for clusters (e.g., a subject rubbing the face, shifting posture, and shrugging shoulders). Although none of these behaviors indicate that a person is lying, they often reveal signs of emotional arousal, discomfort, or ANS activation, especially if they break with the subject’s normal baseline demeanor.

The timing and location of a person’s behavior are critical. For example, if a subject shifts posture, smiles, pauses, and touches the face during a break in small-talk conversation, the behaviors probably are of little value. Conversely, if the individual demonstrates the same pattern immediately following a material question, it may indicate emotional arousal or deceit and would require further questioning.

Keep in mind that these signs are just possible indicators of dishonesty. Plus, some liars are so seasoned that they might get away with not exhibiting any of these signs.

A few of the potential red flags the researchers identified that might indicate that people are deceptive include:

- Being vague; offering few details

- Repeating questions before answering them

- Speaking in sentence fragments

- Failing to provide specific details when a story is challenged

- Grooming behaviors such as playing with hair or pressing fingers to lips

- They may provide too much information or talk a lot

- They may touch or cover their mouth

- They tend to instinctively cover vulnerable body parts

- They tend to shuffle their feet

- They may stare at you without blinking much

- Inconsistency in telling a story again

- Blushing, blinking, fake smiles

- Changing their head position quickly

- Quick changes in their breathing

- Keeping their body rigid and still

- Repetition of words and phrases

- Delay in responding

- Throat clearing.

- Hard swallowing.

- Jaw manipulation.

- Eye pointing.

- Feet pointing.

- Backward head movement

- Backward leaning.

- Guarding the suprasternal notch.

- Look for any sign of discomfort, nervousness, or pacifying as they ask their questions.

- Other conduct by the subject might include answering with palms up (wishing to be believed) or palms down with fingers spread (dominant confidence display).

- They may reply with one shoulder slowly rising toward the ear, indicating weakness, doubt, insecurity, or lack of confidence.

Vocal Cues May Identify Lying

It’s difficult and expensive for regulators to catch corporate fraud, but new insights from psychological science may eventually provide new techniques for spotting deception.

In general, research has shown that people are not very good at spotting lies. People tend to use nonverbal behaviors when they’re trying to spot a lie, but research suggests that vocal cues are much more reliable.

In a comprehensive review of the literature on lying, published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Aldert Vrij (University of Portsmouth) and colleagues give an example of this. Participants in one study were supposed to detect lies in a statement from a convicted murder. The more visual cues the participants reported, the worse their ability to distinguish between truths and lies. Those who mentioned nonverbal behaviors, like gaze aversion or fidgeting, as “tells” for lying had the lowest accuracy at spotting lies. Instead, the study showed that listening carefully to what was being said was the best way to accurately discern the truth from a lie.

To find out more about verbal “tells” for lying, a team of researchers led by Judee Burgoon of the University of Arizona analyzed the speech of corporate fraudsters. Burgoon and colleagues analyzed over 1,000 statements made by the CEO and CFO of one company during six quarterly earnings conference calls. These two company executives were eventually convicted of fraud in multiple securities class action lawsuits.

The corporate earnings conference calls allowed the researchers to accurately compare lying during both scripted, as well as unscripted, speech. These calls are publicly broadcast, and follow a typical pattern; executives give an hour-long presentation on the company’s earnings, followed by an unscripted Q&A with financial analysts.

The research team hypothesized that lying would be more cognitive taxing than telling the truth. Compared to making a truthful statement, it might be easier to use simpler language during a lie.

“Because of the increased cognitive load and the human mind’s finite processing capacity, liars will have difficulty simultaneously maintaining a false story and producing linguistically complex utterances,” Burgoon and colleagues write. “In other words, the more difficult it is for deceivers to concoct a believable response, the more they must resort to simpler language.”

Previous experiments indicate that liars enlist specific strategies to try to distance themselves from their lies. They try to keep statements short and use vague or hedging language (e.g., “I guess” and “maybe” or “could,” “might”). Liars also tend to avoid first-person singular pronouns (e.g., “I,” “me,” “myself”), which are usually a clear signal that the speaker is taking ownership of a statement.

Using special software, the researchers analyzed sound recordings from these calls at a granular level. In order to differentiate between lies and true statements in the recordings, a financial expert was recruited to code the overstatements and lies related to financial fraud.

The analysis confirmed that there were certain speech patterns the executives fell into while lying. Fraud-related speech tended to be more “fuzzy” than non-fraudulent statements; the executives used more hedge words, more distancing language, and more uncertain statements. Contrary to their expectations, the researchers also found that fraudulent statements tended to be longer and more detailed than honest ones.

Executives also used more positive and fewer negative emotional words during fraudulent statements, “suggesting a desire to put a positive spin on what was being reported.”

The researchers caution that the results of this study are limited because this study was based on only two people from one company. However, as different types of data become increasingly available – including call transcripts, online chat logs, social media – researchers will have a bigger pool of materials to draw from.

“For better or worse, new frauds are exposed on a regular basis leading to an expansion of available data. As additional candidate scenarios and features become available, richer analysis is possible,” the researchers conclude.

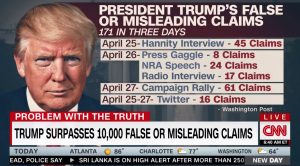

Donald Trump, the Master Liar

Former President Donald Trump made steady news during his presidency for the sheer and often overwhelming number of lies he told daily. A Washington Post Fact Checker analysis shows that he made 30,573 false or misleading claims during his four years in office, with nearly half of them during his final year in office. Someo f Trump’s most infamous liars include his declaration that the coronavirus would disappear like a miracle and various lies about the 2020 election.

“Not only does Trump regularly exaggerate the truth, he frequently denies facts that can be observed directly from video or audio tapes. This has led some professionals to diagnose his lying as compulsive or pathological, and many psychologists have pointed out that he is constantly gaslighting his base—a term that refers to a strategic attempt to get others to question their direct experience of reality.”

Trump’s Lying “Tells”

There are a handful of phrases and body language signs that Donald Trump uses that should raise immediate red flags. When the outgoing Republican president tells a story about large, crying men, overcome with emotion because of some amazing thing Trump claims to have accomplished, it’s a telltale sign he’s brazenly lying.

When he tells a story in which unnamed officials keep calling him “sir,” that’s a dead giveaway, too. Likewise, anytime Trump uses the phrase “ahead of schedule,” he’s obviously trying to deceive people.

The outgoing president used another one, which often gets overlooked. Consider this tweet from, in which Trump peddled obvious nonsense about President-elect Joe Biden’s victory:

“He didn’t win the Election. He lost all 6 Swing States, by a lot. They then dumped hundreds of thousands of votes in each one, and got caught. Now Republican politicians have to fight so that their great victory is not stolen. Don’t be weak fools!”

Trump falsely claimed more than 100 times that Democrats had “rigged” or “stolen” the 2020 election ahead of January’s deadly insurrectionist attack on the U.S. Capitol,” a HuffPost analysis found.

As anyone with an even passing familiarity with reality knows, all of this is ridiculous. Trump didn’t win the states he lost; the GOP ticket didn’t achieve a “great victory”; nothing is being “stolen”; etc.

But the phrase that stood out was “got caught.” In other words, as far as the hapless Republican is concerned, nefarious forces not only conspired against him, these rascals and their scheme have since been exposed for all the world to see.

For those uncomfortable with this nonsense, it’s obvious that Trump’s perceived foes were not, in fact, “caught” doing anything except winning a free and fair presidential election by a rather wide margin.

And therein lies the problem: when the outgoing president uses the phrase “got caught,” Trump is nearly always referring to circumstances in which no one has been caught doing anything of the kind.

Trump’s argued, for example, that Biden “got caught“ engaging in corruption. That never happened. The Republican also believes that Twitter was “caught” working against conservatives, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) “got caught“ cheating, and former FBI Director James Comey “got caught“ doing something (it wasn’t clear what). None of this was true.

Similarly, Trump believes that Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton “got caught“ committing treason by spying on his 2016 campaign, and “radical left” Democrats “got caught“ engaging in some kind of “coup.”

Again, none of these things happened in reality. But the outgoing president not only seems eager to play make-believe, he also seems to believe that by asserting that these ne’er-do-wells “got caught,” people are supposed to assume that his lies have been proven true.They haven’t. “Got caught” is just another telltale sign that the Republican is pushing a line he made up.

Here are some more Trump tells:

- If Trump begins any sentence with, “I can tell you this…,” the words that follow will be categorically untrue.

- When hefinishes a sentence with “…everyone knows that,” the statement preceding it was a lie.

- Frequent sips of water during White House briefings, public speeches, and official announcements are sure signs that an approaching lie has made its way to his lips, caused his mouth go dry.

- His most flagrant “tell” is capitalization in tweets. He almost always capitalizes words or groups of words that are shameless lies. For example, “FAKE NEWS” appears in almost every tweet, so whatever drove him to Twitter to gripe about is unassailably true.

- Trump, like any sociopath, is incapable of love, kindness, or caring. So when he says, “I love (fill in the blank),” don’t believe it. He actually hates whatever is in the blank.

- Trump frequently engages insniffling when he speaks. But this is not due to a cold or allergies, it’s his telltale “sniffle of misinformation.

- If Trump flashes his famous triangle hand gesture, peaking his fingertips in a downward prayer position, he is cooking up a fantastic fable.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.