This extended and thorough article is a 20 minute read.

Did you know what over 45,000,000 people search for happiness on GOOGLE monthly? And that’s just on the main search engine. As amazing as the number is, something struck. This number could potentially be tripled if you take into consideration that happiness seekers might word the phrase differently. Some may search for ways to be happy or how to be happier. Others may take a different approach and look for ways to snap out of a bad mood or how to overcome the blues.

This article is a fairly detailed examination of what is happiness, what it isn’t and suggestions for how to be happy based on research. While it is not as exhaustive as the dozens of books written on the subject, it will give you a good perspective on the topic.

The best book I have read on the subject of happiness isThe Happiness Track by Emma Seppälä.

Defining Happiness

Happiness is a fuzzy concept . Some related concepts include well-being, quality of life, flourishing and contentment. In psychology, happiness is a mental or emotional state of well-being which can be defined by positive or pleasant emotions ranging from contentment to intense. Happy mental states may reflect judgements by a person about their overall well-being.

Since the 1960s, happiness research has been conducted in a wide variety of scientific disciplines, including gerontology, social psychology, clinical and medical research and happiness economics.

In philosophy,happiness is translated from the Greek concept of eudaimonia, and refers to the good life , or flourishing, as opposed to an emotion. Happiness in this sense was used to translate the Greek eudaimonia, and is still used in virtue ethics. There has been a transition over time from emphasis on the happiness of virtue to the virtue of happiness.

Well Being

Well-being, wellbeing, or wellness is a general term for the condition of an individual or group. A high level of well-being means that in some sense the individual’s or group’s condition is positive. Well Being refers to diverse and interconnected dimensions of physical, mental, and social well-being that extend beyond the traditional definition of health. It includes choices and activities aimed at achieving physical vitality, mental alacrity, social satisfaction, a sense of accomplishment, and personal fulfillment.

Research on positive psychology, well-being, eudaimonia and happiness, and the theories of Diener, Ryff, Keyes and Seligmann covers a broad range of levels and topics, including “the biological, personal, relational, institutional, cultural, and global dimensions of life.”. The World Happiness Report series provide annual updates on the global status of subjective well-being. A global study using data from 166 nations, provided a country ranking of psycho-social well-being The latter study showed that subjective well-being and psycho-social well-being (i.e. eudaimonia) measures capture distinct constructs and are both needed for a comprehensive understanding of mental well-being.

Concepts of Happiness Through the Ages and Religions

In the Nicomachean Ethics, written in 350 BCE, Aristotle stated that happiness (also being well and doing well) is the only thing that humans desire for its own sake, unlike riches, honour, health or friendship. He observed that men sought riches, or honour, or health not only for their own sake but also in order to be happy. Note that eudaimonia, the term we translate as “happiness”, is for Aristotle an activity rather than an emotion or a state. Thus understood, the happy life is the good life, that is, a life in which a person fulfills human nature in an excellent way. Specifically, Aristotle argues that the good life is the life of excellent rational activity. He arrives at this claim with the Function Argument. Basically, if it’s right, every living thing has a function, that which it uniquely does. For humans, Aristotle contends, our function is to reason, since it is that alone that we uniquely do. And performing one’s function well, or excellently, is good. Thus, according to Aristotle, the life of excellent rational activity is the happy life. Aristotle does not leave it at that, however. He argues that there is a second best life for those incapable of excellent rational activity. This second best life is the life of moral virtue.

Few who knew the Greek Philosopher Epictetus would have considered him lucky. He was born a slave 2,000 years ago. He lived and died in poverty. He was permanently crippled from a broken leg given to him by his master. They’re not necessarily a list of circumstances that you would wish on anyone you cared about even slightly. The reason his name has lived on for so long, however, isn’t for the misfortunes that he suffered.

He’s remembered as a philosopher. Along with Seneca and the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, his work has done more to spread the wisdom of Stoic philosophy than perhaps anyone else. Even today, the principles he stood for are used by people of all cultures and nationalities.

Without getting into the details, the core idea of Stoicism is to be aware of what you can and can’t control. Once you have that awareness, you can avoid misery by changing what you can control and letting go of what you can’t. It’s an incredibly simple and powerful concept, and that’s why it’s often referred to as the most practical of the ancient and modern philosophies.

What’s admirable about Epictetus is that he showed the extent of its effectiveness through example. In spite of his circumstances, by all records, it appears that he lived a happy and fulfilled life. In fact, his epitaph for himself was the following statement, “Here lies Epictetus, a slave maimed in body, the ultimate in poverty, and favored by the gods.”

Happiness in Religions

Buddhism

Happiness forms a central theme of Buddhist teachings. For ultimate freedom from suffering, the Noble Eightfold Path leads its practitioner to Nirvana, a state of everlasting peace. Ultimate happiness is only achieved by overcoming craving in all forms. More mundane forms of happiness, such as acquiring wealth and maintaining good friendships, are also recognized as worthy goals for lay people. Buddhism also encourages the generation of loving kindness and compassion, the desire for the happiness and welfare of all beings.

Hinduism

In Advaita Vedanta, the ultimate goal of life is happiness, in the sense that duality between Atman and Brahman is transcended and one realizes oneself to be the Self in all. Patanjali, author of the Yoga Sutras, wrote quite exhaustively on the psychological and ontological roots of bliss.

Confucianism

The Chinese Confucian thinker Mencius, who had sought to give advice to ruthless political leaders during China’s Warring States period, was convinced that the mind played a mediating role between the “lesser self” (the physiological self) and the “greater self” (the moral self), and that getting the priorities right between these two would lead to sage-hood. He argued that if one did not feel satisfaction or pleasure in nourishing one’s “vital force” with “righteous deeds”, then that force would shrivel up (Mencius, 6A:15 2A:2). More specifically, he mentions the experience of intoxicating joy if one celebrates the practice of the great virtues, especially through music.

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

Happiness or simcha in Judaism is considered an important element in the service of God. The biblical verse “worship The Lord with gladness; come before him with joyful songs,” (Psalm 100:2) stresses joy in the service of God. A popular teaching by Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a 19th-century Chassidic Rabbi, is “Mitzvah Gedolah Le’hiyot Besimcha Tamid,” it is a great mitzvah (commandment) to always be in a state of happiness. When a person is happy they are much more capable of serving God and going about their daily activities than when depressed or upset.

Roman Catholicism

The primary meaning of “happiness” in various European languages involves good fortune, chance or happening. The meaning in Greek philosophy, however, refers primarily to ethics. In Catholicism, the ultimate end of human existence consists in felicity, Latin equivalent to the Greek eudaimonia, or “blessed happiness”, described by the 13th-century philosopher-theologian Thomas Aquinas as a Beatific Vision of God’s essence in the next life.

According to St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, man’s last end is happiness: “all men agree in desiring the last end, which is happiness. However, where utilitarians focused on reasoning about consequences as the primary tool for reaching happiness, Aquinas agreed with Aristotle that happiness cannot be reached solely through reasoning about consequences of acts, but also requires a pursuit of good causes for acts, such as habits according to virtue. Habits and acts that normally lead to happiness is according to Aquinas caused by laws: natural law and divine law. These laws, in turn, were according to Aquinas caused by a first cause, or God.

According to Aquinas, happiness consists in an “operation of the speculative intellect”: “Consequently happiness consists principally in such an operation, viz. in the contemplation of Divine things.” And, “the last end cannot consist in the active life, which pertains to the practical intellect.” So: “Therefore the last and perfect happiness, which we await in the life to come, consists entirely in contemplation. But imperfect happiness, such as can be had here, consists first and principally in contemplation, but secondarily, in an operation of the practical intellect directing human actions and passions.”

Human complexities, like reason and cognition, can produce well-being or happiness, but such form is limited and transitory. In temporal life, the contemplation of God, the infinitely Beautiful, is the supreme delight of the will. Beatitudo, or perfect happiness, as complete well-being, is to be attained not in this life, but the next.

Islam

Al-Ghazali 1058–1111), the Muslim Sufi thinker, wrote “The Alchemy of Happiness”, a manual of spiritual instruction throughout the Muslim world and widely practiced today. Happiness in its broad sense is the label for a family of pleasant emotional states, such as joy, amusement, satisfaction, gratification, euphoria, and triumph.

Psychological Theories

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a pyramid depicting the levels of human needs, psychological, and physical. When a human being ascends the steps of the pyramid, he reaches self-actualization. Beyond the routine of needs fulfillment, Maslow envisioned moments of extraordinary experience, known as peak experiences, profound moments of love, understanding, happiness, or rapture, during which a person feels more whole, alive, self-sufficient, and yet a part of the world. This is similar to the flow concept of Mihály Csíkszentmihályi. Amitai Etzioni points out that Maslow’s definition of human needs, even on the highest level, that of self-actualization, is self-centered (i.e. his view of satisfaction or what makes a person happy, does not include service to others or the common good—unless it enriches the self). As implied by its name, self-actualization is highly individualistic and reflects Maslow’s premise that the self is “sovereign and inviolable” and entitled to “his or her own tastes, opinions, values, etc.”

Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory relates intrinsic motivation to three needs that contribute to happiness: competence, autonomy, and relatedness, all of which contribute to happiness.

Positive psychology

During the past two decades, the field of positive psychology has expanded drastically in terms of scientific publications, and has produced many different views on causes of happiness, and on factors that correlate with happiness.]Numerous short-term self-help interventions have been developed and demonstrated to improve well-being.

Seligman’s acronym PERMA summarizes five factors correlated with well-being:

- Pleasure(tasty food, warm baths, etc.),

- Engagement (or flow, the absorption of an enjoyed yet challenging activity),

- Relationships (social ties have turned out to be extremely reliable indicator of happiness),

- Meaning (a perceived quest or belonging to something bigger), and

- Accomplishments (having realized tangible goals).

Measurement of happiness

Several scales have been developed to measure happiness:

- The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS) is a four-item scale, measuring global subjective happiness. The scale requires participants to use absolute ratings to characterize themselves as happy or unhappy individuals, as well as it asks to what extent they identify themselves with descriptions of happy and unhappy individuals.

- The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) is used to detect the relation between personality traits and positive or negative affects at this moment, today, the past few days, the past week, the past few weeks, the past year, and generally (on average). PANAS is a 20-item questionnaire, which uses a five-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all, 5 = extremely) A longer version with additional affect scales is available in a manual.

- The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is a global cognitive assessment of life satisfaction developed by Ed Diener. The SWLS requires a person to use a seven-item scale to state their agreement or disagreement (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = neither agree nor disagree, 7 = strongly agree) with five statements about their life.

The UK began to measure national well being in 2012, following Bhutan, which already measured gross national happiness.

The 2012 World Happiness Report stated that in subjective well-being measures, the primary distinction is between cognitive life evaluations and emotional reports. Happiness is used in both life evaluation, as in “How happy are you with your life as a whole?”, and in emotional reports, as in “How happy are you now?,” and people seem able to use happiness as appropriate in these verbal contexts. Using these measures, the World Happiness Reportidentifies the countries with the highest levels of happiness. Etzioni argues that happiness is the wrong metric, because it does not take into account that doing the right thing, what is moral, often does not produce happiness in the way this term is usually used.

Genetic and Brain Research on Happiness

Research in positive psychology has legitimized the study of happiness and brought it to the forefront of the cultural dialogue, simultaneously boosting the prominence of happiness studies and complicating how the term is defined.

Psychologists and neuroscientists have arrived at insights into humanity’s inherent capacity for happiness — what’s known as the “happiness set point” — as well as one’s potential to be more or less happy.

“As a rough generalization, about a third of the factors that determine outcomes of well-being are genetic or biological,” cognitive psychologist Rick Hanson, author of Hardwiring Happiness, told HuffPost. “That leaves about two-thirds that are based on the environment around us and what we do inside ourselves.”

The problem is that the brain is attracted more to negative experiences than positive ones. In Hanson’s analogy, the brain is like Teflon for positive experiences and Velcro for negative ones. His research has found that the simple secret to boosting our happiness levels is to maximize life’s everyday simple pleasures and small joys, which we can do by lingering on positive moments and finding small ways to build more joy into our lives. “If we train ourselves increasingly to look for the positive, we have trained our brain in terms of what it’s primed to see and what it’s scanning for,” said Hanson. Having positive experiences more often tends to increase flows of dopamine, the chemical that tracks rewards, in the brain, which builds out more receptors for dopamine, and over time makes us more sensitive to reward, says Hanson.

Our brains aren’t evolving to make us happier and more content, if anything, the crucible of evolution evolved us to be constantly worried, thinking about dangers and problems, and being anxious. This is an oversimplification – but think about it – 500,000 years ago – who was more likely to reproduce – the person who was fearless and went out into the wild every day staring danger in the face – or the person who was scared to leave camp? The hero ended up getting eaten by a lion and the person who was scared at camp ended up procreating and passing along their genes.

In fact – your brain is a 2 million year old piece of hardware that was programmed to live in a world where we face real physical threats, like tigers and lions and starvation – not a world where the biggest danger posed to us comes in the from of an email from our boss. And that’s not changing any time soon – because there is essentially no evolutionary pressure on humans – we aren’t really evolving towards anything anymore.

Negative Emotions

But what about these negative emotions? The notion that negative emotions are bad for you is also not really the right way to look at it. Here are a few key things to understand about negative emotions.

- Negative emotions are unavoidable.You cannot avoid experiencing negative emotions – and by trying to or by pushing them down, ignoring them, and distracting yourself – you are actually causing these emotions to intensify and become greater. Trying to avoid experiencing negative emotions, paradoxically, makes you experience them more frequently and with more intensity.Tal Ben Shahar – who taught the most popular class in Harvard’s history which was on Happiness – famously says that only two types of people never experience negative emotions – psychopaths and dead people. He has also shared a number of paradoxical strategies to embrace and accept negative emotions and improve your happiness. Emotional perfectionism – or the idea that you should always be in positive emotional states – can cause some serious problems – and worsen the experience of going through negative emotions. Cultivating self compassion and a more realistic perspective that negative emotions are inevitable and natural helps tremendously. Your emotions are messengers trying to send you information. The sooner you accept that and listen to what they are saying, the better off you will be.

- Negative emotions are data, not direction. Negative emotions provide you with meaningful and relevant information that you can use to make decisions, prioritize, and understand that something is going on in your life. Listen to that message. But also know that emotions aren’t necessary correct or right – they don’t mean you have to go in that particular direction, but they are providing you with incredibly useful information that you should listen to and incorporate into your behaviour. In fact, when you look at high stakes performers like stock traders and professional poker players – they don’t try to remove emotion from the equation – they leverage their emotions to improve their decision-making process.

Even though no evidence of a link between happiness and physical health has been found, the topic is being researched by Laura Kubzansky, a professor at the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University. A positive relationship has been suggested between the volume of gray matter in the right precuneus area of the brain and the subject’s subjective happiness score.

Dean Burnett’s book Happy Brain: Where Happiness Comes From, and Why examines the brain’s impact on our happiness. Burnett, a neuroscientist and standup comic, explores some of the inner workings of our brains to reveal how our neural networks support us in experiencing happiness so we can move forward in life and love. Add to that some pretty weird anomalies—like the neurotransmitter serotonin, which modulates mood, being produced primarily by our gut bacteria—and it becomes clear that we don’t understand everything about our brains and happiness. Much of it may be out of our conscious control. “Just embrace the important point: The things that influence our brain’s ability to make us happy extend far beyond just our experiences and personal preferences,” warns Burnett.

Burnett goes on to explain how work, laughter, love, lust, and our age all impact happiness, too, and how that’s mapped in the brain. For example, humor happens when we find something unexpected and incongruent—like an elephant shopping in a supermarket—and can resolve what’s going on by “getting” the joke or solving the puzzle. Perhaps because the ability to come up with novel solutions is a survival skill, our brains reward this activity with the pleasant feeling of being amused. And we have parts of our brains devoted to understanding jokes—namely, the temporal, occipital, and parietal lobes, from which laugher apparently originates.

Not all the things that make us feel good are benign, unfortunately, and the book also explores some of the darker findings around happiness—like schadenfreude, our pleasure at another’s misfortune, and the desire to put others down to make ourselves feel good. Clearly, the reward systems in our brains are not always kind toward others, which is important, if distressing, to know.

Hedonic adaptation is the tendency for humans to quickly adapt to major positive or negative life events or changes and return to their base level of happiness. As a person achieves more success, expectations and desires rise in tandem. The result is never feeling satisfied — achieving no permanent gain in happiness. “The joys of loves and triumphs and the sorrows of losses and humiliations fade with time.” — Sonja Lyubomirsky

After a significant life event, hedonic adaption occurs as a result of cognitive changes. These changes can include a change in values, goals, attention or interpretation of a situation.

For example, after making your first million dollars, a number you had previously thought was significant, you might start thinking one million dollars is really not all that much in the grand scheme of things.

The outcome is that no matter how pleasurable — or how disappointing — a situation is, we return to a happiness “set point.” A happiness set point is where humans generally maintain a constant level of happiness throughout their lives, despite events that occur in their environment.

According to Alex Lickerman M.D., “[One’s happiness set point] is determined primarily by heredity and by personality traits ingrained in us early in life and as a result remains relatively constant throughout our lives. Our level of happiness may change transiently in response to life events, but then almost always returns to its baseline level as we habituate to those events and their consequences over time.”

Politics and Economics

In politics, happiness as a guiding ideal is expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence of 1776, written by Thomas Jefferson, as the universal right to “the pursuit of happiness.”This seems to suggest a subjective interpretation but one that nonetheless goes beyond emotions alone. In fact, this discussion is often based on the naive assumption that the word happiness meant the same thing in 1776 as it does today. In fact, happiness meant “prosperity, thriving, wellbeing” in the 18th century.

Common market health measures such as GDP and GNP have been used as a measure of successful policy. On average richer nations tend to be happier than poorer nations, but this effect seems to diminish with wealth. This has been explained by the fact that the dependency is not linear but logarithmic, i.e., the same percentual increase in the GNP produces the same increase in happiness for wealthy countries as for poor countries. Increasingly, academic economists and international economic organizations are arguing for and developing multi-dimensional dashboards which combine subjective and objective indicators to provide a more direct and explicit assessment of human wellbeing.

Work by Paul Anand and colleagues helps to highlight the fact that there many different contributors to adult wellbeing, that happiness judgment reflects, in part, the presence of salient constraints, and that fairness, autonomy, community and engagement are key aspects of happiness and wellbeing throughout the life course.

Libertarian think tank Cato Institute claims that economic freedom correlates strongly with happiness preferably within the context of a western mixed economy, with free press and a democracy. According to certain standards, East European countries (ruled by Communist parties) were less happy than Western ones, even less happy than other equally poor countries. However, much empirical research in the field of happiness economics, such as that by Benjamin Radcliff, professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame, supports the contention that (at least in democratic countries) life satisfaction is strongly and positively related to the social democratic model of a generous social safety net, pro-worker labor market regulations, and strong labor unions. Similarly, there is evidence that public policies that reduce poverty and support a strong middle class, such as a higher minimum wage, strongly affect average levels of well-being.

It has been argued that happiness measures could be used not as a replacement for more traditional measures, but as a supplement. According to professor Edward Glaeser, people constantly make choices that decrease their happiness, because they have also more important aims. Therefore, the government should not decrease the alternatives available for the citizen by patronizing them but let the citizen keep a maximal freedom of choice. Good mental health and good relationships contribute more than income to happiness and governments should take these into account.

Happiness Around the World

A worldwide survey of more than 136,000 people in 132 countries included questions about happiness and income, and the results reveal that while life satisfaction usually rises with income, positive feelings don’t necessarily follow.

You may have noticed that many books, blogs and inspirational speakers make large and silly promises. Break free from fear and you’ll soar like an eagle, reverse the aging process and attract a bevy of sexy and appreciative lovers. As one self-help book puts it, “Bliss is available to anyone at anytime, no matter how difficult life may be.” And that is the most hurtful myth of all—the idea that every one of us can create ourselves a great day no matter how painful our current circumstances. We need only to choose happiness along with a brighter attitude and a new set of skills.

Of course, each of us can move in the direction of experiencing less fearand more calmness, love and peace. There are many paths we can take to become more whole and centered, to navigate our relationships with greater clarity and conviction, and to grab a little dignity and peace along the way. We can’t stop bad things from happening, but we can stop our relentless focus on how things were or how we want them to be, and develop a deeper appreciation for what we have now. We can work on becoming our best and bravest selves. But it is arrogant and deeply dishonest to tell people that they can transform their own reality and find joy no matter how dreadful their circumstances. Such a falsehood only breeds silence and shame about our honest suffering.

Sooner or later the universe will send every one of us a crash course in vulnerability, meaning that you—or someone you love—will get a great big lesson in all the painful emotions that we try so hard to avoid. It is not useful to deny that fear and suffering define the human condition as much as happiness and joy.

The Dark Side of Happiness

These studies have revealed four ways that happiness might be bad for us.

Too much happiness can make you less creative—and less safe. Happiness, it turns out, has a cost when experienced too intensely.

For instance, we often are told that happiness can open up our minds to foster more creative thinking and help us tackle problems or puzzles. This is the case when we experience moderate levels of happiness. But according to Mark Alan Davis’s 2008 meta-analysis of the relationship between mood and creativity, when people experience intense and perhaps overwhelming amounts of happiness, they no longer experience the same creativity boost. And in extreme cases like mania, people lose the ability to tap into and channel their inner creative resources.

What’s more, psychologist Barbara Fredrickson has found that too much positive emotion—and too little negative emotion—makes people inflexible in the face of new challenges.

Not only does excessive happiness sometimes wipe out its benefits for us—it may actually lead to psychological harm. Why? The answer may lie in the purpose and function of happiness. When we experience happiness, our attention turns toward exciting and positive things in our lives to help sustain the good feeling. When feeling happy, we also tend to feel less inhibited and more likely to explore new possibilities and take risks.

Take this function of happiness to the extreme. Imagine someone who has an overpowering drive to attend only to the positive things around them and take risks of enormous proportions. They might tend to overlook or neglect warning signs in their environment, or take bold leaps and risky steps even when outward signs suggest gains are unlikely.

People in this heightened ‘happiness overdrive’ mode engage in riskier behaviors and tend to disregard threats, including excessive alcohol consumption, binge eating, sexual promiscuity, and drug use. In a 1993 study, psychologist Howard S. Friedman and colleagues found that school-aged children rated as “highly cheerful” by parents and teachers had a greater risk of mortality when followed into adulthood, perhaps because they engaged in more risk-taking behaviors. All these results point to one conclusion: Happiness may be best when experienced in moderation—not too little, but also not too much.

Happiness is not suited to every situation.

Our emotions help us adapt to new circumstances, challenges, and opportunities. Anger mobilizes us to overcome obstacles; fear alerts us to threats and engages our fight-or-flight preparation system; sadness signals loss. These emotions enable us to meet particular needs in specific contexts.

The same goes for happiness—it helps us to pursue and attain important goals, and encourages us to cooperate with others. But just as we would not want to feel angry or sad in every context, we should not want to experience happiness in every context.

As psychologist Charles Carver has argued, positive emotions like happiness signal to us that our goals are being fulfilled, which enables us to slow down, step back, and mentally coast. That’s why happiness can actually hurt us in competition. Illuminating studies done by Maya Tamir found that people in a happy mood performed worse than people in an angry mood when playing a competitive computer game.

Not all types of happiness are good for you.

“Happiness” is a single term, but it refers to a rainbow of different flavors of emotion: Some make us more energetic, some slow us down; some make us feel closer to other people, some make us more generous. But do all types of happiness promote these benefits? It seems not. In fact, a more nuanced analysis of different types of happiness suggests that some forms may actually be a source of dysfunction.

One example is pride, a pleasant feeling associated with achievement and elevated social rank or status. As such, it is often seen as a type of positive emotion that makes us focus more on ourselves. Pride can be good in certain contexts and forms, such as winning a difficult prize or receiving a job promotion. Research by Sheri Johnson and Dacher Keltner finds that when we experience too much pride or pride without genuine merit, it can lead to negative social outcomes, such as aggressiveness towards others, antisocial behavior, and even an increased risk of mood disorders such as mania.

Pursuing happiness may actually make you unhappy.

Not surprisingly, most people want to be happy. We seem hardwired to pursue happiness, and this is especially true for Americans—it’s even ingrained in our Declaration of Independence. Yet is pursuing happiness healthy? Groundbreaking work by Iris Mauss has recently supported the counterintuitive idea that striving for happiness may actually cause more harm than good.

In fact, at times, the more people pursue happiness the less they seem able to obtain it. Mauss shows that the more people strive for happiness, the more likely they will be to set a high standard for happiness—then be disappointed when that standard is not met. This is especially true when people were in positive contexts, such as listening to an upbeat song or watching a positive film clip. It is as if the harder one tries to experience happiness, the more difficult it is to actually feel happy, even in otherwise pleasant situations.

The science of emotional diversity

There are studies that show over-pursuing happiness actually may be detrimental to your mental and physical health. People who have “emodiversity”—meaning they express a full range of emotions including anger, worry and sadness—are actually healthier than those whose range tends to be mostly on the positive side.

In a study of over 35,000 people, researchers found that “people high in emodiversity were less likely to be depressed than people high in positive emotion alone.” In another study of 1,300 Belgians, those with greater emodiversity used fewer medications, didn’t go to the doctor as often, exercised more, ate better, and had all-around better health than those with more limited emotional range.

Too much intense happiness can affect our creative juices too. In one study measuring mood and creativity, Mark Alan Davis found that when we experience extreme or intense happiness we tend not to tap into our creativity as much. In extreme cases we can get manic and lose our connection to creativity. Not that you need to be melodramatic to be creative. Happy people are creative too. But at some point only going for the gusto can be counter-productive if you’re trying to access your muse.

Another study found that those who are consistently on the high end of happiness curve tend to be less flexible in adapting to challenging situations. It becomes harder to adjust when things go south. What’s more, those who are in constant pursuit of positive experiences are more likely to engage in risky behaviors like sexual promiscuity and substance abuse. This extreme happiness/risky behavior syndrome was also confirmed in a 1993 study. Children who were regarded as “highly cheerful” tended to have a higher probability of mortality as adults probably due to riskier behavior.

Indeed, when we try too hard to attain happiness we may be setting ourselves up for its opposite. Researcher Iris Mauss and colleagues have shown that sometimes people chase happiness to an unrealistic degree, which can actually end up leading to major disappointment. It can turn into a vicious cycle where the harder you try for happiness the more elusive it becomes.

“A culture that talks about happiness as much as we do is giving the sign that we’re concerned about happiness, and I mean concerned in a slightly negative way,” said Darrin McMahon, a historian at Florida State University and author of Happiness: A History. “We obsess about happiness, and that may be an indication that we’re not actually all that happy.”

“For Aristotle, happiness isn’t a feeling, but an evaluation of a life lived well,” said McMahon. “That begins to shift in a profound way in the 18th century … people start defining happiness as a feeling, an emotion, as what puts a smile on your face.”

With the rise of utilitarian principles in the 1700s, the idea that the individual should maximize pleasure and minimize pain became prevalent in the cultural conversation. The 18th century British economist and founding father of utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham — who believed that societies and individuals should act in such a way as to promote the “greatest happiness for the greatest number” — defined happiness in this way, as a pleasure/pain calculus.

As a result of this cultural shift, people were presented with a novel prospect: “They can be happy, and they should be happy,” said McMahon.

The idea of happiness was central to some of the 18th century’s defining movements. Rousseau’s Social Contract posited that the rules of society must be created with humanity’s happiness in mind. And of course, in the United States, the Declaration of Independence positioned happiness (or at least its pursuit) as an “unalienable right” of the individual.

The legacy of those Enlightenment principles still informs our conception of happiness, even as happiness itself has taken on functions more often associated with religion. According to McMahon, happiness, rather than service to God or spiritual transcendence, has come to be seen as the ultimate aim of life in many cultures. “[Happiness] is really the last great organizing principle of a life,” McMahon said. “We no longer live our lives according to beauty or honor or virtue. We want to live in order to be happy.”

Like Rubin, McMahon associates the rising concern and preoccupation with happiness with two main factors: declining religious belief and economic prosperity.“The key question then becomes why,” McMahon explained. “To really be concerned about your happiness is a total luxury: It only happens when everything else is taken care of. To care about happiness in a really sustained, neurotic way … is on one level a sign of our prosperity.” This shift in priorities is even reflected in how we’ve started to quantify national success, as gross national happiness has the attention of leaders alongside gross national product.

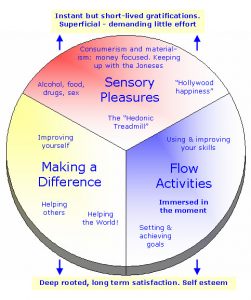

In the pursuit of pleasure and joy, people tend to fall into the trap of running on the so-called hedonic treadmill — chasing after pleasures and external recognition that they believe will bring happiness, rather than finding more pleasure in the experiences they’re already having.

According to the treadmill theory, outlined in a 2006 paper by Ed Diener, Richard E. Lucas and Christie Napa Scollon, good or bad things temporarily affect our happiness levels, but when those experiences come to an end, we quickly return to neutral. In a consumer culture, it’s easy to see how an obsession with happiness can amplify a hedonic treadmill scenario, in which one is constantly looking outside the self for the next quick fix to boost happiness.

“We keep ratcheting up what is luxury and what is pleasure, and yet we also fall back to a kind of baseline,” said McMahon. “A market economy operates on that, but it’s not necessarily designed to make us happier… In some ways this will always be a losing proposition.”

A number of industries, particularly self-help, benefit from this arrangement. In the last several decades, a growing desire to buy happiness has made self-help into money-making mega-genre. Meanwhile, positive psychology has become a staple of the corporate world, promising to make employees happier, and therefore more productive and more creative.

“There are snake oil salesmen in the business world who are making massive amounts of money by selling positive psychology to corporations as a way to organize workforces,” said McMahon. “But there’s not a whole lot of science behind what they’re claiming, at times.”

McMahon also questions the motives driving the corporate positive psychology movement. “It’s good and bad — they want you to flourish, but they also want to get more out of you,” he said. “These psychological techniques are being used to increase productivity, and that’s not a bad thing, but sometimes you wonder what the ultimate goal is. Is it profit maximization, or having flourishing people?”

The trouble lies not in the field of positive psychology or in the research coming out of it — but in the proposition that happiness is something that can be easily bought or crafted.

“There’s a certain tendency in our culture to want to graft some kind of happiness onto an existing structure,” Hanson said. “If you just fill in the blank — get this car, find the right shade of lipstick, go on vacation in Mexico, lose those five pounds — suddenly you’ll be happier and have the fulfillment you want in life … Let’s be clear: The main happiness industry in America is the advertising industry.”

A New Disease Of Western Societies

One risk inherent in our obsession with the pursuit of happiness is that we will begin to fear or devalue painful, negative emotions and challenging experiences.

For Australian social researcher Hugh Mackay, the notion that individuals should do everything for the sake of happiness is a dangerous one. In his book The Good Life, Mackay argues that this philosophy has led to a new disease among Western societies: “fear of sadness.”

Mackay explains that it’s wholeness, not happiness, that we should be after: It’s a really odd thing that we’re now seeing people saying, “Write down three things that made you happy today before you go to sleep,” and “Cheer up” and “Happiness is our birthright,” and so on. We’re kind of teaching our kids that happiness is the default position — it’s rubbish. Wholeness is what we ought to be striving for and part of that is sadness, disappointment, frustration, failure; all of those things which make us who we are. Happiness and victory and fulfillment are nice little things that also happen to us, but they don’t teach us much … I’d like just for a year to have a moratorium on the word “happiness” and to replace it with the word “wholeness.” Ask yourself “Is this contributing to my wholeness?” and if you’re having a bad day, it is.

Does Money Make You Happier?

Does money really buy you happiness? The debate continues, and most people still pursue more money as the answer to being happier.

“The public always wonders: Does money make you happy?” said University of Illinois professor emeritus of psychology Ed Diener, a senior scientist with the Gallup Organization. “This study shows that it all depends on how you define happiness, because if you look at life satisfaction, how you evaluate your life as a whole, you see a pretty strong correlation around the world between income and happiness,” he said. “On the other hand it’s pretty shocking how small the correlation is with positive feelings and enjoying yourself.”

Like previous studies, the new analysis found that life evaluation, or life satisfaction, rises with personal and national income. But positive feelings, which also increase somewhat as income rises, are much more strongly associated with other factors, such as feeling respected, having autonomy and social support, and working at a fulfilling job.

This is the first “happiness” study of the world to differentiate between life satisfaction, the philosophical belief that your life is going well, and the day-to-day positive or negative feelings that one experiences, Diener said. “Everybody has been looking at just life satisfaction and income,” he said. “And while it is true that getting richer will make you more satisfied with your life, it may not have the big impact we thought on enjoying life.”

Are wealthier people really happy? Sure, there are philanthropists like Warren Buffet and Bill Gates, who have given billions of their net worth away and have made the world a better place. But, according to psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky, they are an exception. Lyubormisky argues that American families who make over $300,000 a year donate to charity a mere 4% of their incomes. She cites studies at the University of Minnesota where they have demonstrated that merely glimpsing dollar bills makes people less generous and approachable and more egocentric. An international team of researchers reported in the professional journal Psychological Science that although wealth may grant us opportunities to purchase many things, it simultaneously impairs our ability to enjoy those very things.

Lyubomirsky also cites a study by researchers at the University of Liege in Belgium that showed that the wealthier the workers were, the less likely they were to display a strong capacity to savor positive experiences in their lives. Furthermore, simply being reminded of money dampened their savoring ability. Lyubomirsky concludes that because wealth allows people to experience the best that life has to offer, it ultimately undermines their ability to savor life’s little pleasures.

While a great deal of research has been devoted to the predictors of happiness and life satisfaction around the world, researchers at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand wanted to know one thing: What is more important for well-being, providing people with money or providing them with choices and autonomy? “Our findings provide new insights into well-being at the societal level,” they wrote in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, published by APA. “Providing individuals with more autonomy appears to be important for reducing negative psychological symptoms, relatively independent of wealth.”

“Across all three studies and four data sets, we observed a very consistent and robust finding that societal values of individualism were the best predictors of well-being,” the authors wrote. “Furthermore, if wealth was a significant predictor alone, this effect disappeared when individualism was entered.” In short, they found, “Money leads to autonomy but it does not add to well-being or happiness.”

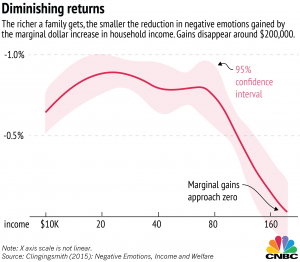

Previous research has shown that higher income, greater individualism, human rights and social equality are all associated with higher well-being. The effect of money on happiness has been shown to plateau — that is, once people reach the point of being able to meet their basic needs, more money leads to marginal gains at best or even less well-being as people worry about “keeping up with the Joneses.” These patterns were mostly confirmed in their findings.

A collaborative paper by economist Richard Easterlin — namesake of the “Easterlin Paradox” and founder of the field of happiness studies — offers the broadest range of evidence to date demonstrating that a higher rate of economic growth does not result in a greater increase of happiness. Across a worldwide sample of 37 countries, rich and poor, ex-Communist and capitalist, Easterlin and his co-authors shows strikingly consistent results: over the long term, a sense of well-being within a country does not go up with income.

In contrast to shorter-term studies that have shown a correlation between income growth and happiness, this paper, to be published the week of Dec. 13 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, examined the happiness and income relationship in each country for an average of 22 years and at least ten years.

“This article rebuts recent claims that there is a positive long-term relationship between happiness and income, when in fact, the relationship is nil,” explained Easterlin, USC University Professor and professor of economics in the USC College of Letters, Arts & Sciences. Easterlin and a team of USC researchers spent five years reassessing the Easterlin Paradox, a key economic concept introduced by Easterlin in the seminal 1974 paper, “Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence.”

“Simply stated, the happiness-income paradox is this: at a point in time both among and within countries, happiness and income are positively correlated. But, over time, happiness does not increase when a country’s income increases,” explained Easterlin, whose influence has created an entire subfield of economic inquiry.

Easterlin expands on findings from other researchers that show a positive relationship between life satisfaction and GDP, demonstrating instead that they are the short-term effects of economic collapse and recovery, and do not hold up over the long term. “With incomes rising so rapidly in [certain] countries, it seems extraordinary that no surveys register the marked improvement in subjective well-being that mainstream economists and policy makers worldwide expect to find,” Easterlin said.

For examples, Easterlin points to Chile, China and South Korea, three countries in which per capita income has doubled in less than 20 years. Yet, over that period, both China and Chile showed mild, not statistically significant declines in life satisfaction. There is an optimal point to how much money it takes to make an individual happy, and that amount varies worldwide, according to research from Purdue University.

“That might be surprising as what we see on TV and what advertisers tell us we need would indicate that there is no ceiling when it comes to how much money is needed for happiness, but we now see there are some thresholds,” said Andrew T. Jebb, the lead author and doctoral student in the Department of Psychological Sciences. “It’s been debated at what point does money no longer change your level of well-being. We found that the ideal income point is $95,000 for life evaluation and $60,000 to $75,000 for emotional well-being. Again, this amount is for individuals and would likely be higher for families.”

Emotional well-being, or feelings, is about one’s day-to-day emotions, such as feeling happy, excited, or sad and angry. Life evaluation, really life satisfaction, is an overall assessment of how one is doing and is likely more influenced by higher goals and comparisons to others.

“And, there was substantial variation across world regions, with satiation occurring later in wealthier regions for life satisfaction,” Jebb said. “This could be because evaluations tend to be more influenced by the standards by which individuals compare themselves to other people.”

Jebb’s area of expertise is in industrial-organizational psychology. The senior author on the paper is Louis Tay, an assistant professor of psychological sciences. The research is published in Nature Human Behaviour.The research is based on data from the Gallup World Poll, which is a representative survey sample of more than 1.7 million individuals from 164 countries, and the estimates were averaged based on purchasing power and questions relating to life satisfaction and well-being. For reporting this study, the amounts are reported in U.S. dollars, and the data is per individual, not family.

The study also found once the threshold was reached, further increases in income tended to be associated with reduced life satisfaction and a lower level of well-being. This may be because money is important for meeting basic needs, purchasing conveniences, and maybe even loan repayments, but to a point. After the optimal point of needs is met, people may be driven by desires such as pursuing more material gains and engaging in social comparisons, which could, ironically, lower well-being.

“At this point they are asking themselves, ‘Overall, how am I doing?’ and ‘How do I compare to other people?'” Jebb said. “The small decline puts one’s level of well-being closer to individuals who make slightly lower incomes, perhaps due to the costs that come with the highest incomes. These findings speak to a broader issue of money and happiness across cultures. Money is only a part of what really makes us happy, and we’re learning more about the limits of money.”

Happiness and Inequality

What is happiness inequality? It’s the psychological parallel to income inequality: how much individuals in a society differ in their self-reported happiness levels—or subjective well-being, as happiness is sometimes called by researchers.

Since 2012, the World Happiness Report has championed the idea that happiness is a better measure of human welfare than standard indicators like wealth, education, health, or good government. And if that’s the case, it has implications for our conversations about equality, privilege, and fairness in the world.

We know that income inequality can be detrimental to happiness: According to a 2011 study, for example, the American population as a whole was less happy over the past several decades as income inequality has risen. The authors of a companion study to the World Happiness Report hypothesized that happiness inequality might show a similar pattern, and that appears to be the case.

In their study, they found that countries with greater inequality of well-being also tend to have lower average well-being, even after controlling for factors like GDP per capita, life expectancy, and individuals’ reports of social support and freedom to make decisions. In other words, the more happiness equality a country has, the happier it tends to be as a whole. Among the world’s happiest countries—Denmark, Switzerland, Iceland, Norway, and Finland—three of them also rank in the top 10 for happiness equality.

On an individual level, the same link exists; in fact, individuals’ happiness levels were more closely tied to the level of happiness equality in their country than to its income equality. Happiness equality was also a stronger predictor of social trust than income equality—and social trust, a belief in the integrity of other people and institutions, is crucial to personal and societal well-being.

“Inequality of well-being provides a better measure of the distribution of welfare than is provided by income and wealth,” assert the World Happiness Report authors, who hail from the University of British Columbia, the London School of Economics, and the Earth Institute.

How much happiness inequality does your country have?

To do this analysis, the researchers asked a simple question of nearly half a million people worldwide: On a scale of 0-10, representing your worst possible life to your best possible life, where do you stand? The most common answer is 5—but as you can see in the graph on the right, many people rate themselves as less happy than that. If the world had perfect happiness equality, everyone would provide the same answer to this question. Researchers also assessed the level of happiness inequality in each of 157 countries, taking into account how much people’s happiness ratings deviated from each other.

Topping the rankings for happiness equality is Bhutan, a country whose government policy is based on the goal of increasing Gross National Happiness. Those with the most happiness inequality are the African countries of South Sudan, Sierra Leone, and Liberia.

The United States ranks 85th for happiness inequality, meaning that subjective well-being—not just wealth—is spread relatively unevenly throughout our society. We fare worse than New Zealand (#18), our neighbor Canada (#29), Australia (#30), and much of Western Europe. Note that these aren’t the happiest countries; they are simply the places without a huge happiness gap between people. Even so, as described above, happiness equality is associated with greater happiness overall.

Unfortunately, trends in happiness inequality are going in the wrong direction: Up. Comparing surveys from 2005-2011 to 2012-2015, the researchers found that well-being inequality has increased worldwide. More than half of the countries surveyed saw spikes in happiness inequality over that period, particularly those in the Middle East, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa. Meanwhile, fewer than one in ten countries saw their happiness inequality decrease.

The good news is that promoting happiness equality doesn’t require taking happiness from some people and giving it to others. Instead, these findings underscore the importance of building a society and a culture that cares about individual well-being, not just economic growth. Some countries—such as Bhutan, Ecuador, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela—have already taken this stance, appointing happiness ministers to work alongside their government officials. As report co-editor and Earth Institute director Jeffrey Sachs writes: “Governments can ensure access to mental health services, early childhood development programs, and safe environments where trust can grow. Education, including moral education and mindfulness training, can play an important role. Human well-being [should be] at the very center of global concerns and policy choices in the coming years.”

What Prevents Us From Being Happy?

Turns out, a study about this has been done and has recently reached its conclusion. The 20-year old study conducted by Dr. Thomas Gilovich, a psychology professor at Cornell University concluded with a simple and straightforward answer: Don’t spend your money on material things. According to the study, happiness acquired through material ownership dulls rapidly over time and this is due to three reasons:

- Yesterday’s shiny and new become today’s dull and boring.

- The next best thing — Once the allure fades, we move on in search of the next thing that will rouse our excitement.

- Comparisons breed envy —Dave Ramsey, author of The Total Money Makeover: A Proven Plan for Financial Fitness who did a talk at TED put it best: “We buy things we don’t need with money we don’t have to impress people we don’t like.”“One of the enemies of happiness is adaptation,” Gilovich said. “We buy things to make us happy, and we succeed. But only for a while. New things are exciting to us at first, but then we adapt to them.”

- We become what we live —“Our experiences are a bigger part of ourselves than our material goods,” said Gilovich. “You can really like your material stuff. You can even think that part of your identity is connected to those things, but nonetheless they remain separate from you. In contrast, your experiences really are part of you. We are the sum total of our experiences.”

- No two experiences are the same —We tend to put deeper thought in decisions that will affect our lives. Given the same circumstances and the same choices, no two individuals will think exactly alike. Their own unique personality and values come into play which makes the whole experience difficult to gauge and assess.

- Consistency throughout the whole experience —The study also looked at the effects of anticipation and observed that it causes excitement for a new experience while it had the opposite on anticipation for material things and caused impatience instead. From start to finish, the anticipation we feel for new experiences are consistent.

- Constant reminder versus a fleeting one —Not all purchases we make are planned and/or fulfill a certain need or purpose. We sometimes buy on impulse and experience what’s called as Buyer’s Remorse.

Ways We Sabotage Our Happiness

- Thinking that you have to be just like someone else, or to match their apparent success.

- Thinking that wealth, achievement, looks, intelligence, talent, and status equate to fulfillment

- Thinking that you need to be perfect in order to be lovable.

- Judging yourself harshly.

- Being hungry for approval.

- Rehashing past mistakes or fearing future failures.

- Obsessing over outcomes.

- Ruminating about what can’t be changed.

- Thinking that being alone means being unha.ppy.

- Thinking that you have to say “yes” to every request.

- Clinging to resentment.

- Believing that you can change someone else.

- Inventing and dwelling upon painful inner dramas that have little or no basis in fact.

- Thinking that mistakes, setbacks, and failures doom you for life.

- Blaming yourself for things you can’t control.

- Blaming other people and situations for things you CAN control, or passively accepting what you COULD change.

- Creating suffering through bad habits and addictions.

- Comparing yourself to others.

- Falling for the belief that you can’t change.

- Trying to give to others without giving to yourself.

- Focusing on lack instead of abundance.

- Waiting for the day when you finally arrive.

- Excessive thinking and worrying about the future.

- Putting up with things that do not serve you.

- Complaining about life instead of taking responsibility.

What Does Research Say About How to Be Happy?

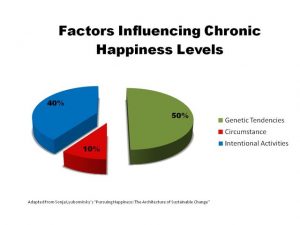

According to psychologists, circumstances are responsible for only about 10% of our personal levels of happiness. Studies have shown that regardless of what happens to people – winning the lottery or losing a limb – their happiness levels tend to return to what they were before the event in about two months. This phenomenon is called the hedonic treadmill or hedonic adaptation.

Researchers say that another 50% of our happiness is determined by our biology, and more specifically, genetically determined personality traits like “being sociable, active, stable, hardworking and conscientious.” Twins who had similar scores in key traits — extroversion, calmness and conscientiousness, for example — had similar happiness scores, but these similarities disappeared once the traits were accounted for.

Not all is lost, however. 40% of your happiness is determined by your thoughts, actions, and behaviors. According to Buddha, this is enough to liberate you from suffering, if you channel this potential in the right thoughts, actions and behaviors. Science agrees — there is a lot you can do to influence your happiness levels.

Scientists spent 75 years studying happiness and this is what they learned. It’s the longest running study on happiness, ever. It’s hard to measure happiness – it means different things to different people and it can’t be seen. However the brave scientists at Harvard University decided to measure it anyway – and they might have conquered it! Psychiatrist Robert Waldinger who is the current director of the study detailed the findings of the study in a fascinating TED Talk in January 2016.

The study known as the Grant Study, and it is the longest running study on happiness ever. The scientists looking into happiness in adult development wanted to analyze what enhanced the wellbeing of an individual rather than what deteriorated it. So, for 75 years they tracked the lives of 724 men, asking on a yearly basis how they were coping in every area of their lives, 60 of these men are still alive and still participating. The participants were from two groups: the first were sophomore students at Harvard in 1938, when the study first began and the second were children from one of the poorest areas of Boston, who came from poverty-stricken backgrounds.

Researchers closely monitored the lives of those involved over the course of the study using interviews, questionnaires, brain scans, blood tests, medical records and talking to their loved ones. As the study evolved alongside their lives, the experts also began to talk to their wives and children.

The revolutionary research was the first of its kind in the world and it has produced some surprising – but lovely – results. The biggest discovery of all was that good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Those who were in unhappy relationships or were lonely were more likely to suffer from pain, discontent and lead unhealthy lifestyles.Nearly 1,200 Germans explored this question in a recent study—and then Julia M. Rohrer and her colleagues followed up with them a year later to find out how happy they felt. The researchers found not all roads lead to happiness.

In surveys, study participants first identified how satisfied they were with their life on a scale of 0-10, and then wrote down their ideas for maintaining or boosting their life satisfaction in the future. After a year, they reported their life satisfaction again and answered some questions about how they had spent their time. Analyzing the data, the researchers could distinguish between two different types of happiness strategies: social and individual. Some goals—like seeing friends and family more, joining a nonprofit, or helping people in need—put participants into contact with other people. The other type of goal includes staying healthy, finding a better job, or quitting smoking—things that don’t necessarily involve spending time with people.

Ultimately, people who wrote down at least one socialstrategy tended to follow through and spend more time socializing that year, and they (in turn) became more satisfied with their lives. They were the people who committed to teach their son to swim or be more understanding of others, to go on a trip with their partner or meet new people.

Meanwhile, people who focused on individual goals didn’t improve their life satisfaction over the year. In fact, the self-focused road to happiness was even less effective than having no plans for action at all, which was the case for about half the participants. Those people were either relatively content—writing “Everything is fine” or “I wouldn’t change much”—or they hoped for changes in external circumstances, like the country’s politicians.

These findings back up an earlier study, which suggested that people who intensely pursue happiness aren’t always more content. That was only true in cultures that define happiness in terms of social engagement and helping others (like East Asia and Russia, but not Germany or the United States). What seems true across cultures is that social connections are key to well-being. For example, very happy people are highly social and tend to have strong relationships; kids with a richer network of connections grow up to be happier adults; and socializing is one of the most positive everyday activities. But this is one of the few studies to actually comparesocial and individual paths to happiness—and find that connecting with others might be inherently more rewarding.

Or, the researchers suggest, perhaps social goals are simply easier to attain. You could argue that it only takes a few phone calls to start spending more time with friends, but eating healthier requires constant and repeated effort—and goals like finding a new job aren’t entirely under your individual control. People who focus on social goals might just achieve them more often, deriving some contentment from that.

A 2015 research study published in the Journal of Religion and Health suggests being grateful may heighten hopefulness, a prerequisite to happiness. The study reveals that those who are more thankful for who they are, and what they have, are more hopeful. The research also finds people who are more hopeful are also physically healthier.

According to a 2009 research study published in the journal Cerebral Cortex, thankfulness arouses your hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is the area of your brain that controls stress. While helping to combat stress, the study also reveals gratitude revs up the ventral tegmental section of your brain, which is responsible for producing the sense of pleasure.

Because happiness is a state of mind, feeling confident in yourself is essential. In 2014, Lu Hung Chen and Chia-Huei Wu published a research study in the Journal of Applied Sports Psychology that examines whether gratitude enhances the self-esteem of athletes. Upon conclusion of the two-part study, the researchers determine athletes having higher levels of gratitude improved their self-esteem over a six-month time period when they possessed higher emotional trust in their coaches.

People’s happiness is often derailed when bad things happen. This can especially be the case when you suffer from an illness. In 2003, the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology published a research study conducted by Robert A. Emmons and Michael E. McCullough. The study required 65 participants diagnosed with neuromuscular diseases to fill out a journal daily for three weeks. They were placed into a gratitude group or a control group.

The participants were encouraged to complete the daily activity during the early evening hours before they became sleepy. The results of the study suggest keeping a gratitude journal causes people with neuromuscular diseases to experience an improved sense of wellbeing and more positive moods. A 2012 research study published in Social Psychological and Personality Science examines the hypothesis that gratitude is associated with diminished aggression. The findings imply being thankful motivates people to display compassion and concern for others.

According to the study, gratitude also encourages prosocial behavior. Aggression, purposefully harming someone who wishes to avoid the harm, is the opposite of the motivation to improve the welfare of others. Unsurprisingly, the cross-sectional, longitudinal, experimental designs, and experience sampling evidence collected in the study shows that gratitude is linked to reduced aggression.

Unlike thoughts, the emotions don’t live entirely in the mind, they are also associated with bodily sensations. Thanks to a new study, for the first time we now have a map of the links between emotions and bodily sensations. Finnish researchers induced different emotions in 701 participants and then got them to color in a body map of where they felt increasing or decreasing activity.

The right kind of happiness doesn’t just feel great, it also benefits the body, right down to its instructional code. A recent study examined the pattern of gene expression within the cells responsible for fighting off infectious diseases and defending the body against foreign materials. Amongst people experiencing higher levels of ‘doing good’ happiness, there was a stronger expression of antibody and antiviral genes. While doing good and feeling good both make us feel happy, it’s doing good that benefits us at the genetic level.

What has happened to people’s happiness all around the world as they’ve faced the economic crisis? How have they coped with job losses, less money coming in, the sense of despair and lack of control over a nightmare that seems to have no end? One answer is: some have pulled together. Data from 255 metropolitan areas across the US found that communities that pull together — essentially doing nice little things for each other like volunteering and helping a neighbour out — are happier. Social capital has a protective effect: people are happier when they do the right thing.

Acting like an extrovert — even if you are an introvert — makes people all around the world feel happier, recent research suggests. The findings come from surveys of hundreds of people in the US, Venezuela, the Philippines, China and Japan. Across the board, people reported that they felt more positive emotions in daily situations where they either acted or felt more extroverted. Participants in the study were told to act in an outgoing way for 10 minutes and then report how it made them feel. Even amongst introverts — people who typically prefer solitary activities — acting in an extroverted way gave them a boost of happiness.

Emotions expressed online — both positive and negative — are contagious, a new study concludes. One of the largest ever studies of Facebook examined the emotional content of one billion posts over two years. Software was used to analyze the emotional content of each post. It turned out that positive emotions spread more strongly than the negative, with positive messages being more strongly contagious then negative.

With increasing age, people get more pleasure out of everyday experiences. A recent study asked over 200 people between the ages of 19 and 79 about happy experiences they’d had that were both ordinary and extraordinary.

Across all the age-groups in the study, people found pleasure in all sorts of experiences; both ordinary and extraordinary. But it was older people who managed to extract more pleasure from relatively ordinary experiences. They got more pleasure out of spending time with their family, from the look on someone’s face or a walk in the park. Younger people, meanwhile, defined themselves more by extraordinary experiences.

Surprisingly, people are often wrong about the type of goals that will make them happiest. New research suggests that certain concrete goals for happiness work better than abstract goals. The study found that acts performed in the service of a concrete goal (making someone smile) made the givers themselves feel happier than an abstract goal (making someone happy). By thinking in concrete ways about our goals for happiness, we can minimize the gap between our expectations and what is actually possible.

Mundane, everyday experiences can provide unexpected joy down the line, new psychological research finds. In one study, 135 students were asked to create a time capsule at the start of the summer which included:

- a recent conversation,

- the last social event they’d attended,

- an extract from a paper they’d written,

- and three favorite songs.

At the time, they also predicted how they’d feel about these items when they opened the capsule three months later. Despite being relatively mundane, the students significantly under-estimated how surprised and curious they would be when they opened it. The study is a reminder of how we tend to undervalue the happiness we can get from everyday events.

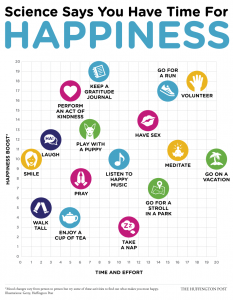

Here are some other things that contribute to happiness:

Going for a walk in nature, particular among trees, can raise your level of happiness. In the study, a group of 38 Northern Californians (18 women and 20 men) were split up into two groups — one who took a 90-minute walk in nature and another that did the same walk in the city. The nature walkers reported having fewer negative thoughts about themselves after the walk than before the walk, while the urban walkers reported no change. What’s more, fMRI brain scans revealed less activity in the subgenual prefrontal cortex (sgPFC), a brain region that may play a key role in some mood disorders and has been linked with patterns of negative thought, according to the study. Those who went on the urban walk did not show any of these benefits, the study found.

Do things you do when you’re happy — even if you’re not. Experiencing positive emotions not only appear to have the power to neutralize negative ones, but can also encourage people to be more proactive. “Positive emotions may aid those feeling trapped or helpless in the midst of negative moods, thoughts, or behaviors — for example, grief, pessimism, or isolation — spurring them to take positive action,” write a team of UC Riverside psychologists in a recent paper summarizing these findings.

Participate in cultural activities.Visiting a museum or seeing a concert is yet another way to boost your mood. A study that examined the anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction of over 50,000 adults in Norway offered an interesting link: People who participated in more cultural activities, like attending a play or joining a club, reported lower levels of anxiety and depression as well as a higher satisfaction with their overall quality of life. So get out there and participate!

Listen to sad songs.Happiness is entirely subjective, meaning that what makes one person happy might affect someone else differently. However, listening to sad music seems to be a common activity that’s been linked with increased happiness around the globe. In a study that looked at 772 people on the eastern and western hemispheres, researchers found that listening to sad music generated “beneficial emotional effects such as regulating negative emotion and mood as well as consolation,” the researchers write in their paper.

Set small realistic goals based upon positive habits. If you’re one of those people who like to make to-do lists on a regular basis, then listen closely: When you’re setting your goals, it’s better to be specific and set goals you know you can achieve. For example, instead of setting a goal like “save the environment,” try to recycle more. Those two examples were tested on a group of 127 volunteers in a study published last year. The first group were provided a series of specific goals like “increase recycling,” while the second group had broader goals like “save the environment.” Even though the second group completed the same tasks as the first group, the people in the second group reported feeling less satisfied with themselves than the first group. The people in the second group also reported a lower overall sense of personal happiness from completing their goal, the scientists report.

Write down your feelings. Ever heard someone say, ‘If you’re angry at someone, write them a letter and don’t send it’? While that might seem like a waste of time, science reveals recording your feelings is great for clarifying your thoughts, solving problems more efficiently, relieving stress, and more. A team of psychologists recently hit on a neurological reason behind why this simple act might help us overcome some emotional distress.

The researchers studied brain scans of volunteers who recorded an emotional experience for 20 minutes a day for 4 sessions. They then compared the brain scans with volunteers who wrote down a neutral experience for the same amount of time. The brain scans of the first group showed neural activity in a part of the brain responsible for dampening strong emotional feelings, suggesting that the act of recording their experience calmed them. This same neural activity was absent in the volunteers who recorded a neutral experience.

Spend money on others, not yourself. When you’ve had a really bad day, you might have the urge to go and buy your favorite comfort food or finally purchase that pair of shoes you’ve been eyeing for the last three months. However, research shows that you’ll feel happier if you spend that money on someone else, instead of yourself. Case in point: A 2008 study gave 46 volunteers an envelope with money in it wherein half were instructed to spend the money on themselves and the other half put the money towards a charitable donation or gift for someone they knew. The volunteers recorded their happiness level before receiving the envelope and after spending the money by the end of that same day. Sure enough, the researchers discovered that those who spent their money on others had a higher level of happiness than those who spent the money on themselves.