By Ray Williams

October 3, 202

We probably have all had the experience of an apology. It could be receiving (or hoping to receive) and apology from someone who has said or done something that hurts you in some way, or it is your behavior that prompts you to give (or want to give) an apology for your transgression.

Are apologies important? What makes them effective? Do simple apologies such as saying “I’m sorry” sufficient to repair the damage done? When is an apology not an apology? Do they benefit the giver of the apology as much as the recipient? How is forgiveness connected to apologies? Are personal apologies the same as institutional or organizational apologies?

All of these questions are important. This article tries to shed some light on those questions, based on research. A suggested six step process is provided.

Why do People or Institutions Apologize?

One common reason given for why people apologize is “negative affect alleviation.” People feel guilty, and an apology removes the guilt? This view dates to a Freudian model of human behavior where humans have a residue of emotion — in this case, guilt — which when accumulated, causes distress until emptied.

In the book Mea Culpa: A Sociology of Apology and Reconciliation, Nicholas Tavuchis sees apologies as a complex social system designed to maintain relationships and establish membership in community, a kind of social exchange that restores social order.

Apologies as a fundamental part of a healthy society are important for several reasons. First, they can mend or heal damaged or broken relationships either between individuals, or even groups of people or countries. Second, apologies can provide an opportunity for the transgressor to either amend their reputation, or provide assurances that the transgression is not a reflection of a pattern of behavior, and therefore not likely to be repeated in the future.

Successful consummate apologies may raise the moral threshold of a society because they promote positive externalities such as increased trust and mutual respect. It is in such a milieu that previously disempowered individuals and groups are using their elevated status to remind others of profound inequities and insult. Apologies are a civilized way to redress these inequities. The motives behind an apology reveal what role an apology plays or, at least, what it might achieve, for the person delivering it.

An apology is a peace offering; an act of humility and humanity; a moderating force in the face of retribution; and a mental salve. The person who receives an apology — if it satisfies his or her expectations — can also experience significant benefits. An apology is a social transaction that involves a significant exchange of power, an exchange that is crucial for the restoration of balance and harmony.

The Emotional Benefits of Apology

- A person who has been harmed feels emotional healing when he is acknowledged by the wrongdoer.

- When we receive an apology, we no longer perceive the wrongdoer as a personal threat.

- Apology helps us to move past our anger and prevents us from being stuck in the past.

- Apology opens the door to forgiveness by allowing us to have empathy for the wrongdoer.

The Elements of an Effective Apology

Considerable psychological and other research have identified the essential elements of a good apology, which can be applied to both an individual or institutional circumstance: The transgressor must be genuinely remorseful.

- An apology should not be forced or insincere. If it is, it will often be seen that way, lose its impact, or not be accepted or believed.

- The transgressor should deliver the apology with honesty and vulnerability. When the transgressor is willing to share their emotions honesty about the mistake, the impact on others carries greater credibility and emotional significance.

- The transgressor takes personal and full responsibility for their actions and behavior. This means no equivocations, excuses or “non-apologies.”

- The transgressor explains that they did and the reasons why it was wrong. This also includes admitting the negative impact the mistake has made on others. This is not the same as providing excuses or rationalizations, but rather an honest admission of the process by why the transgressor made the mistake.

- The transgressor uses “I” statements (or in the case of an institution the individual(s) indicating personal responsibility and avoiding vague reference or projecting blame on others or circumstances.

- The transgressor actually uses the words “I am sorry.” Again, modifiers or language that can essentially avoid personal responsibility such as “It’s unfortunate,” “it’s a sad situation that.”

- The transgressor offers to or makes amends. This means committing to actions that are a promise or commitment of non-repetition or offering to something to correct the injury or harm done.

- The transgressor asks for forgiveness. This can be a controversial element for several reasons. First, if the request for forgiveness early may or may not help the victim or situation. Timing is of the essence. Second, asking for forgiveness should not be used as a manipulative tool to absolve the transgressor of responsibility to make amends.

- The transgressor forgives themselves. Part of the process of healing is to more effectively deal with the problem of guilt without removing the need for remorse. The transgress needs to heal as well.

If for some reason, the transgressor can’t craft an apology with all these components, the researchers say, the most important element is accepting personal responsibility. Acknowledging that the transgressor made a mistake and make it clear that they were at fault is necessary. The researchers also argue the transgressor should never apologize for the injured party’s feelings, but rather take full responsibility for the transgressor’s behavior. For example,

If you say, “I’m sorry if you were hurt by my words,” that is not an apology, and focuses the responsibility to the person hurt or offended. Instead, a statement like “I’m sorry I said hurtful things” shows the offender takes responsibility.

The second most important element, the research found, is to offer a repair or make amends.

While the transgressor might not necessarily be able to undo the damage, there are usually steps you can take to reduce the harm. And the least effective part of an apology? Asking the offended person wronged “do you forgive me?”

Michael E. McCullough, Steven J. Sandage, M.S., and Everett L. Worthington, examined in their article published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology whether the effect of apology on our capacity to forgive is due to our increased empathy toward an apologetic offender. They discovered that much of why people find it easy to forgive an apologetic wrongdoer is that apology and confession increase empathy, which heightens the ability to forgive. McCullough, who is the director of research at the privately funded National Institute for Healthcare Research in Rockville, Maryland, believes that apology encourages forgiveness by eliciting sympathy. He and his colleagues published research in that supports this hypothesis.

A study by David De Cremer,Chris Reinders Folmer and Madan M. Pillutla published in Psychological Science, finds that people aren’t very good at predicting how much they’ll value an apology. Apologies have been in the news a lot the last few years in the context of the financial crisis, says De Cremer: “Banks didn’t want to apologize because they didn’t feel guilty but, in the public eye, banks were guilty”. But even when some banks and CEOs did apologize, the public didn’t seem to feel any better. “We wondered, what was the real value of an apology?”

“I think an apology is a first step in the reconciliation process,” De Cremer says. But “you need to show that you will do something else.” He and his authors speculate that, because people imagine that apologies will make them feel better than they do, an apology might actually be better at convincing outside observers that the wrongdoer feels bad than actually making the wronged party feel better.

De Cremer found that people often overestimate the extent that an apology will make them feel better. Across a series of experiments, people displayed greater trusting behavior when they imagined receiving an apology compared to when they actually received one.

“An apology seems to be only the first step of the reconciliation process, because people do not react as positively toward an apology as they think they will,” De Cremer and colleagues explain.

Apologizing is not just for the victim, but also for the perpetrator, argue Jonathan Cohen and David De Cremer published their study on apologies which found that people often overestimate the extent that an apology will make them feel better. They argue that the factors which seem to have the biggest impact in the apology are acknowledging personal responsibility, an explanation for why the violation occurred and an offer of repair or amends.

A study from the University of Pennsylvania offers some insight a connection between apologies and the psychology of trust-both violation and repair. Maurice Schweitzer, Michael Haselhuhn and Alison Wood, published an article in the journal Psychological Science, they expert on organizations and decision making, decided to explore the idea of trust recovery in the lab. He and his colleagues- -wanted to see if basic beliefs about moral” character” influence trust violations and forgiveness. They also wanted to see if they could modify those beliefs-and in doing so make people more or less forgiving.

The scientists recruited a large group of volunteers to play an elaborate game involving breaches of trust and reparations. But before the game started, they primed the volunteers with different beliefs about moral character. Some were nudged to believe that people can change-that people can and do become more ethical and trustworthy if they sincerely set their minds to it. The others were primed with the opposite belief-basically that scoundrels will always be scoundrels. This core belief is surprisingly easy to manipulate, and the researchers did it here simply by having the volunteers read essays arguing for one belief or the other.

The trust game that followed goes like this: You have $6, which you can either keep or give to another person. If you give it away, it triples in value to $18, which the recipient can either keep or split with you, $9 apiece. So initially giving away the $6 is obviously an act of trust. But in order to study trust recovery, the scientists put the volunteers through several rounds of the game. In the early rounds, the recipient (actually a computer) violated trust by keeping the $6 a couple times in a row. Then the recipient apologized and promised to be more trustworthy from now on. Then there was one final opportunity to be either trusting or not.

So does believing in the possibility of change shape people’s ability to forgive-and trust again? It does, dramatically, the researchers concluded, trust was easily eroded and they also easily restored it-but only in those who believed in moral improvement. Those who believed in a fixed moral character, incapable of change, were much less likely to regain their trust after they were betrayed.

These results have practical implications for anyone trying to make amends and reestablish trust-in recovery, in business, in love-and yes, in politics. Apologies and promises may not be enough in some cases, and indeed it may be more effective to send a convincing message about the human potential for real moral transformation. The best way to send that message, of course, is to demonstrate that one’s behavior has changed on a continuing basis.

Obstacles That Prevent Transgressors from Apologizing

In an article published in the journal Current Directions in Psychological Science, author Karina Schumann examined the psychology of offering an apology, including the barriers to apologizing an how to overcome them. She describes the barriers that prevent transgressors from apologizing: “ I propose that three main barriers to apologizing emerge from this growing literature: (a) feeling low levels of concern for the victim or one’s relationship with the victim, (b) perceiving that apologizing will threaten one’s self-image, and (c) perceiving that apologizing will be ineffective at eliciting forgiveness. Moreover, apologizing carries with it the risk of being rejected, as a victim can choose to disregard the apology and deny the transgressor forgiveness. I propose that transgressors who feel low concern for the victim or their relationship with the victim are less willing to engage in this relationship-promotive behavior. Supporting the existence of this barrier, recent studies have demonstrated that transgressors who report lower versus higher levels of empathic concern, perspective taking, and care for others’ welfare report lower proclivity to apologize, transgressors who intentionally harmed the victim and consequently feel less guilty are less willing to apologize, and transgressors who are more averse to relationship closeness offer less comprehensive and more defensive apologies. In addition, several studies suggest that people who are disproportionately focused on the self rather than others are less willing to apologize. “

Joshua Guilfoyle and colleagues examined the element of emotional self-control as a critical component of the apology giver, in their article published in Basic and Applied Social Psychology. They found in their research that “transgressors with high self-control are more apologetic than those with low self-control.”

Aaron Lazare, in his book, On Apology, argues that apologizing too soon may be counterproductive, and misses a step in reconciliation. This perspective is reflected in the arguments of Frank Partnoy, author of Wait: The Art and Science of Delay, argues we have to resist the impulse to react to everything immediately, which doesn’t allow some time for the injured party to vent or deal with their emotions.

The Non-Apology

On a daily basis now, we see politicians from heads of state down to the local level, not just refusing to apologize and take responsibility but giving non-apologies — the appearance of an apology.

Editors at Oxford Dictionaries recently added an entry for “non-apology,” defining it as a statement that takes the form of an apology but doesn’t sufficiently acknowledge responsibility or regret. Oxford also added an entry for “apology tour,” a series of public appearances by a well-known figure to express regret over a wrongdoing.

“I want to apologize is not an apology.” It’s no more an apology than “I want to lose weight” is a loss of weight. “I’m sorry if you were offended,” or “I’m sorry your feelings are hurt” are not apologies. These imply that the inured party may be too sensitive, and the problem is their perception of what happened. “I’ve really been upset over what I did,” or “I’m losing sleep over this,” are not apologies. They put the focus on the transgressor’s well-being and ask the offended party to show compassion and caring for the transgressor. “Everybody makes mistakes, and I’m not perfect,” is not an apology. It avoids personal responsibility by projecting the responsibility onto others. “I hope you won’t hold this against me,” is not an apology. It’s passive aggressive at best and aggressive at the worst because it implies some retribution or punishment of the injured party. For example, someone says “I called you an idiot but I’ve been under a lot of stress/have too much going on.” This is not an apology but a rationalization or excuse. The giveaway is often the word “but.”

The non-apology often puts the blame on the victims or critics of the perpetrator, because the message is “If anyone is stupid or too insensitive to be offended by what I did, then I guess I apologize, but only because their unreasonableness forces me to do so to make the problem go away.” This illustrates a lack of empathy, insincerity and a refusal to accept personal responsibility for their own acts. Language is also manipulated in a non-apology to give the appearance of an apology.

Here are some other examples of non-apologies:

When apologies are offered in public life, they tend to be the sort that subtly shifts the blame: “I apologize if anyone was offended.” This is, of course, another way of saying, “I’m sorry you are so sensitive.” No one was ever mollified by such an apology, but somehow it remains in use.

Using the passive-voice: “mistakes were made” has become a parody of the political non-apology, often using the conditional — an “if” clause. This short-circuits the apology process by placing the onus on the offended party to confirm that an offense actually took place.

Closely related to the conditional apology is the reliance on indefinite pronouns such as “anyone” and “anything” to avoid naming the offense. Carried to the extreme, reliance on indefinites ends up like this: “I’m apologizing for the conduct that it was alleged that I did, and I say I am sorry.”

Frequently these days we hear politicians, business leaders or media personalities who blame “a poor choice of words” or say they “regret that my words were misinterpreted,” or the ever popular, “I misspoke.” All of these phrases are illustrative of a reluctance or avoidance of accepting personal responsibility for an offense, leaving the impression that it was momentary minor slip of the tongue. At it’s worse, it is gaslighting, implying that the audience of the transgression has done something wrong by not understanding or hearing what was actually said.

Institutional Apologies

Not only have individuals had to make personal apologies, so have governments, and public institutions. What are the differences if any? That has been the question for researchers in recent years to answer. And there have been some good examples and some bad ones.

Karina Schumann and Michael Ross published a study of government apologies for historical injustices published in Political Psychology, in which they say: “Throughout history, governments of many countries have committed deliberate discriminatory acts against minorities, ranging from unfair taxes to slavery and mass murder. These government actions were often legal, approved by legislatures and courts as well as the majority of citizens. In retrospect, these actions seem unjust, but what, if anything, should current governments do about them? Does it matter how governments respond to historical injustices that occurred decades or even centuries ago? Their response seems to matter a great deal to some previously victimized groups. Around the world, groups are demanding that governments acknowledge and apologize for historical injustices.”

Sometimes governments acknowledge the earlier injustice, but argue that it is too late, too difficult, or too expensive to do anything about it. Such arguments are used to justify the U.S. federal government’s refusal to apologize and pay compensation for slavery. Sometimes governments maintain that their countries have already done much to alleviate historical injustices, and they need to focus on current problems. Sometimes governments establish inquiries dedicated to detailing and explaining earlier injustices, for example, the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions in South Africa and Canada, the authors explain. Finally, with increasing frequency in recent decades, governments sometimes apologize for historical injustices. These apologies may or may not include offers of financial compensation.

A government apology represents a formal attempt to redress a severe and long-standing harm against an innocent group. Because these harms are more severe than most interpersonal transgressions, a simple “sorry” is unlikely to suffice. Also, a government apology is public and aimed at present and future audiences that include members of the non-victimized majority, as well as the previously victimized group. As some of these audiences may know little about the injustice, “everything counting as the apology must be spelled out; nothing can be taken for granted or remain ambiguous” the researchers explain.

An expression of remorse indicates that a government believes that an apology is warranted and cares about the victims. By assigning responsibility for the injustice outside the victim group, a government explicitly asserts the innocence of the victims. An apology that assigns responsibility can therefore help offset a common tendency to blame victims for their own troubles.

An admission of injustice further absolves the victims of blame. It assures the victimized group that the current government upholds the moral principles that were violated and is committed to upholding a legitimate and just social system. By acknowledging harm and victim suffering, a government validates the victims’ pain and corroborates their suffering for outsiders. A promise of forbearance can work to restore trust between groups; it indicates that the government values the victims and their group and is willing to work to keep them safe. Finally, by offering repair (e.g., financial compensation to victims or their families), governments demonstrate that their apology is sincere —colloquially, they are willing to put their money where their mouth is. If an apology serves all of these psychological needs, it should theoretically make the victims and other members of their group feel better about themselves, the majority group, their government, and their country.

For example, in his apology before the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the former President of South Africa, F. W. de Klerk, explicitly described the harm and suffering caused by Apartheid. “I apologize . . . to the millions of South Africans who suffered the wrenching disruption of forced removals in respect of their homes, businesses and land. Who over the years suffered the shame of being arrested for past law offences. Who over the decades and indeed centuries suffered the indignities and humiliation of racial discrimination. Who for a long time were prevented from exercising their full democratic rights in the land of their birth. Who were unable to achieve their full potential because of job reservation. And who in any other way suffered as a result of discriminatory legislation and policies.”

Also, a promise of forbearance is necessary for an institutional apology. For example, in apologizing for the internment of Japanese Canadians during WWII, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney offered “our solemn commitment and undertaking . . . that such violations will never again in this country be countenanced or repeated.”

The final component of an interpersonal apology by institutions is an offer of repair, in the form of either individual or community based compensation. For instance, in apologizing for the Chinese Head Tax, Canadian Prime Minister Harper stated “that Canada will offer symbolic payments to living head tax payers and living spouses of deceased payers”. Rather than giving payments to specific individuals, Britain offered restitution for its past involvement in the slave trade by increasing aid to Africa and launching an immunization facility that is projected to save the lives of five million African children a year.

An example of a bad institutional apology is that issued by President Bush and Condoleezza Rice and Donald Rumsfeld over the abuse of Iraqi prisoners held by the United States military in the Abu Ghraib prison. Photos and documented testimony showed U.S. soldiers taking pleasure in torturing and mocking naked Iraqi prisoners. American soldiers and prisoners from both Abu Ghraib torturings and Guantánamo Bay detention camps have come forward along with officials to the papers and 60 Minutes drawing the stress-positions and the torturing that the U.S. Army committed to the prisoners.

The U.S. apology for Abu Ghraib contained several of these deficiencies. For a national offense of this magnitude, only the president has the standing to offer an apology. It appeared that other spokespersons were apologizing on behalf of President Bush, or even to shield him. That was the first deficiency. Second, the apology must be directed to the offended people, such as the Iraqis, the American public, and the American military. Instead, in President Bush’s most widely publicized comments, he apologized to the king of Jordan and then reported his conversation second hand to the offended parties. He never directly addressed the Iraqis, the American public, or the American military. Third, the person offering the apology must accept responsibility for the offense. Neither President Bush nor Condoleezza Rice accepted such responsibility. Instead, they extended their sorrow to the Iraqi people. Feeling sorry does not communicate acceptance of responsibility. The president also avoided taking responsibility as the commander-in-chief by using the passive voice when he said, “Mistakes will be investigated.” In addition, he failed to acknowledge the magnitude of the offense, which is not only the immediate exposure of several humiliating incidents, but a likely pervasive and systematic pattern of prisoner abuse occurring over an extended period of time, as reported by the International Red Cross.

In the U.S. government’s apologies for the Abu Ghraib incident, there was not a full acknowledgement of the offense and an acceptance of responsibility, so there could be no affirmation of shared values. In addition, there was no restoration of dignity, no assurance of future safety for the prisoners, no reparative justice, no reparations, and no suggestion for dialogue with the Iraqis. So it should not come as a surprise that the Iraqi people—and the rest of the world—were reluctant to forgive the United States.

Corporate Apologies

Disputes in the United States have more often than not seen the complete absence of apologies. For example, the congressional hearings concerning potential malfeasance behind the investment banking profits and bonuses in the U.S. in 2009–2010 was accompanied by, at best, lukewarm remorse and few explicit apologies by companies such as Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, Citi- group, and AIG who received government bailouts (Gordon and Hall 2010). Indeed, many of the major actors involved in the crisis, such as Robert Rubin of Citigroup, explicitly refused to apologize for their role in the crisis.

Daryl Koehn has researched the topic of corporate apologies extensively which was published in Business Ethics Quarterly.

He says that “collective and interpersonal apologies are similar insofar as neither typically is legalistic. By contrast, corporate apologies are usually negotiated with and written by lawyers who are concerned to protect the corporation and its officers from lawsuits. Collective apologies very often involve reparations, which are usually not discussed in most interpersonal or corporate apologies. Interpersonal apologies usually require that the apologizer show remorse, while remorse is not frequently communicated in corporate. Corporate apologies frequently center on specific measures the firm is taking to restore trust in its brand,. Corporate apologies are proffered at a time when the exact causes of a harm with which the firm is associated may not yet be clear (e.g., Ashland Oil CEO John Hall’s apology for a polluting, ruptured oil tank that may or may not have been properly legally permitted and that may or may not have been sabotaged). Most often, corporate apologies are delivered by the firm’s CEO or owner depending on the size of the company.”

Koehn goes on to explain that an ethically good corporate apology ideally will lay out some action steps for restoring trust by repairing the breach. “So, on this score, too, the CEO needs to indicate that he or she acknowledges that the firm erred in some particular way. Chrysler CEO Lee Iacocca’s apology for Chrysler dealers’ practice of disconnecting odometers, driving the cars, reconnecting the odometers, and then selling them as new is ethically good insofar as he named the specific wrongdoing: ‘Disconnecting odometers is a lousy idea. That’s a mistake we won’t make again at Chrysler. Period.’”

It is true that some corporate mistakes involve little or no liability and that corporate guilt frequently can readily be established regardless of whether the firm has offered an apology. It is also true that apologies do not necessarily entail an admission of guilt under the law and sometimes create no legal liability for the firm. Some states have now passed “apology laws” affording some protection to hospitals/health care firms who issue apologies.

Koehn argues that “We can contrast ethically better apologies in which CEOs assume an appropriate degree and type of responsibility with those in which CEOs hide behind the collective. Leaders of firms involved in wrongdoing sometimes use the pronoun ‘we’ or refer to the ‘team’ when describing the firm’s deeds or strategies. For example, the bankers at the center of the financial collapse consistently referred to their ‘teams’ and to the practices of other bankers when alluding to the causes of the debacle. These bankers suggested that many parties were to blame for the meltdown. Yet, when everyone is responsible, no one is. Furthermore, when CEOs fail to cast them- selves as responsible at least for preventing additional harm of the sort referenced in their apologies, their words can wind up damaging trust even further .”

There have been several cases of bad CEO apologies. These speech acts express regret or sympathy but do not serve to restore trust because the speaker does not accept (on behalf of the firm) responsibility for the harm and suffering resulting from specific acts of the firm or its leader. Martha Stewart consistently denied that she was involved in insider trading or the obstruction of justice. She never apologized to her employees, customers or stockholders for the wrongdoing for which she was convicted and imprisoned,

In many cases, CEOs say that they are sorry but then characterize what the injured parties view as wrongdoing in such a way that the CEO’s responsibility is lessened. Consider the prepared statement Citigroup CEO Chuck Prince read when he testified before the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission in April 2010: “Let me start by saying I’m sorry. I’m sorry the financial crisis has had such a devastating impact for our country. I’m sorry about the millions of people, average Americans, who lost their homes. And I’m sorry that our management team, starting with me, like so many others could not see the unprecedented market collapse that lay before us.

Prince hides behind talk of the “team” and conspicuously avoids mentioning the particular actions by financial institutions that so troubled thoughtful observers: the pushing of inappropriate mortgages, the use of unsafe credit default swaps to improve the bank’s balance sheet, the lowering of mortgage standards that enabled non-creditworthy borrowers to get loans, etc. I would not require that, in his apology. Prince admit to possibly criminal conduct on the part of Citigroup. But he could have at least mentioned by name some of the worrisome and suspect practices widely believed to be rampant in the mortgage industry as a whole. Or he could have admitted to some specific errors in business judgment on the part of Citigroup’s leadership. Courts generally do not hold executives and boards of directors legally responsible for business judgment mistakes. Instead, Prince regrets his failure to foresee that which was allegedly unprecedented and, therefore, likely unforeseeable. In other words, his apology is not an apology at all because no one needs to take responsibility for the failure to be omniscient.

To summarize: Simply saying “I am sorry” is not sufficient for an ethically good corporate apology. A CEO’s apology qualifies as such only when the apologizer explicitly assumes responsibility for seriously addressing some particular problem for which he or she is reasonably being held accountable by the audience.

When British Petroleum’s CEO Tony Hayward after the BP oil spill that badly polluted the Gulf of Mexico whined that he would “like to have his life back,” the relatives of the eleven men who were killed on the oil rigs were incensed by Hayward’s apparent callousness. Hayward eventually would get his life back, but these victims would forever be dead. Hayward’s earlier expression of regret (which arguably was not a genuine or ethically good apology—see endnote 5), followed by this inappropriate lament, suggested that his character was insensitive and petty. Instead of allaying the audience’s anger, Hayward fanned the flames. To take another case: Bernie Madoff’s investment securities firm was unmasked as a giant Ponzi scheme. Madoff was arrested and convicted for securities fraud. His courtroom apology talked more about the harm he had caused to his immediate family than to the thousands of investors whom he had swindled. Given that his family gained and retained millions from his wrongdoing, Madoff’s unempathetic expression of contrition left many listeners (including the judge) feeling that Madoff still did not appreciate how unjustly he had behaved. Again, the apology intensified the anger of those hearing the apology rather than working to rebuild any sense that Madoff’s firm (which continued to operate) could be trusted in the future.

Effective Corporate Apologies Include Six Elements

Whether you’re the company CEO or the summer intern, knowing how to say you’re sorry—and have people actually believe you—is an important business skill. If your subordinate is caught embezzling, or you’re the head of a company in the midst of a massive public safety scandal, simply saying “I’m sorry” probably isn’t going to cut it.

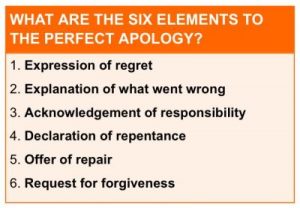

New research from psychological scientists Roy Lewicki , Beth Polin, and Robert Lount Jr. published in Negotiation and Conflict Management Research confirms that not all apologies are equally effective. Across two studies Lewicki and colleagues found that the most compelling apologies include six distinct elements:

- An expression of regret: A statement in which the violator expresses how sorry they are for the offense. Example: “I am truly sorry for speaking to you in a disrespectful manner.”

- An explanation of what went wrong. A statement in which the reasons for the offense are described to the victim. Example: “I got angry when you correctly pointed out that I was interrupting you all the time. When you asked me not to interrupt, I angrily swore at you.”

- Acknowledgment of responsibility. A statement which demonstrates the violator understands how the behavior is a transgression. For example: “I swore at you in anger, and you are not responsible for my actions. I take full responsibility with no excuses.”

- Declaration of repentance. A statement in which the violator expresses their promise to not repeat the offense. For example. “I am truly sorry, and I promise (commit) to not do that again.”

- Offer of repair. A statement extending a commitment to work toward rebuilding trust between the violator and victim. For example: “I would be grateful if you would agree to have future conversations in which I’m able to exercise self-control and demonstrate good conversation skills.”

- Request for forgiveness. A statement asking for the victim to pardon the violators’ actions. For example: “Can you forgive me for speaking to you in a disrespectful and abusive manner?”

Their results suggest that if you’ve really messed up, you’ll do best if you use as many of these six components as possible in your apology; although some of these components were much more important than others.

“Our findings showed that the most important component is an acknowledgement of responsibility. Say it is your fault, that you made a mistake,” Lewicki said in a press release.

Across both studies, the best apologies were also the most thorough: The more elements included in the apology, the higher it was rated. And, as expected, apologizing over a lack of personal integrity was less effective than apologizing for a simple mistake.

Apologies in the Workplace

Are the characteristics of an apology the same in workplace situation compared to a personal relationship? That’s the question that Ryan S. Bisel and Amber S. Messersmith sought to answer in their research, published in Business Communication Quarterly. They propose a four part structure to an effective workplace apology. Specifically, and in alignment with other research, their model includes four components: a narrative account of the offense; voicing regret with an explicit apology-functioning speech act; promising forbearance; and offering reparations.

Here is an example of a workplace apology recommended by Bisel and Messersmith with the four elements:

“Dear Mr. Burton:

Please accept my sincerest apology for the troubling incident you recently ha at our 6th Street Branch in which you were denied the purchase of an money order. Our policy does in fact allow for the sale of money orders to non-customers. Unfortunately, this policy was not communicated clearly to new staff. Please be assured this matter has since been addressed with all staff members and this mistake will not happen in the future.

Again I am sorry that we failed to provide the highest quality of service which you deserve an we deeply regret missing the opportunity to welcome you to Central Bank as our new customer. We would like to provide you with 10 free money orders as a token of our appreciation.

Sincerely,

Brad Chearle

President.”

Apology Components

- Explain your error: “you were denied the purchase of a money order.”

- Say you’re sorry: “sincerest apology; deeply regret; I am sorry.”

- Promise of forbearance: “Please be assured this matter has since been…and this mistake will not happen in the future.”

- Offer to restore: “10 free money orders.”

The Forgiveness Connection

Apology and forgiveness are two sides of the same coin. While apology is an expression of regret or remorse for an offense or injury, forgiveness is the pardon for something that has been done.

Alfred Alan and colleagues published an article in Behavioral Sciences & the Law in which they examined the connection between forgiving and apology, and concluded that a predictor of granting forgiveness was whether the victims perceived the transgressors as being truly sorry in their apologies.

Ward Struthers and colleagues study the interrelationship between forgiveness and apologies and published their results in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. They found that when there were intentional transgressions, apologies were less likely to be accepted and forgiveness was less likely than if the transgression was perceived as unintentional.

Forgiveness is a power held by the victimized, not a right to be claimed. The ability to dispense, but also to withhold, forgiveness is an ennobling capacity and part of the dignity to be reclaimed by those who survive the wrongdoing. Even an individual survivor who chooses to forgive cannot, properly, forgive in the name of other victims. To expect survivors to forgive is to heap yet another burden on them.

Analysts of interpersonal apologies frequently address the question of forgiveness and the conditions under which recipients are willing or unwilling to forgive apologizers for their transgressions. The definition of forgiveness varies: for some analysts, mere acceptance of an apology implies forgiveness, while for others, forgiveness is a deep psychological process in which the recipient of the apology relinquishes his anger or desire for vengeance, “surrendering the right to get even,” and is able to focus on other matters, thus “moving on” (to resort to popular parlance).

Forgiving does not mean excusing, condoning, ceasing to blame, losing respect for the victims, or forgetting that wrong-doing occurred. What happens in forgiving is that we relinquish our feeling of hatred and resentment and accept that the wrongdoer has repented and reformed.

Personal Note:

In the current state of acrimony and division in America the importance of apologies for offenses and transgressions have never been more needed to help heal the nation and it’s people

Read my new book: Toxic Bosses: Practical Wisdom for Developing Wise, Ethical and Moral Leaders