By Ray Williams,

February 23, 2021

In spite of many good intentions, we often give in to temptation. There are so many choices to make each daythat many of them are made on autopilot. We often rely on easy rules of thumb rather than consciously weighing up the options. This automatic processing helps us deal with the complex challenges of too much choice, but it can also compromise the results. When using our in-built autopilot, the decision context ends up influencing our final choice, with the mere visibility and dominance of certain options (such as delicious-looking croissants and pretty coffee drinks) being powerful factors in determining the outcome.

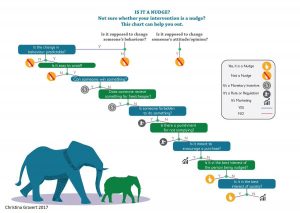

There’s a number of ways to change behaviors: through fear and punishment, through incentives and rewards and more formal structures like laws and regulations. Each of these require a direct intervention or “push” or “pull” to change our behaviors. Some experts and psychologists believe the push (or negative reinforcement) method can result in resistance by people because they are aware of what’s happening.This is where the concept of “nudge” comes in, which is a subtle way of changing behavior without the person being conscious of the change.

Defining Nudge

Nudge is a concept in behavioral economics, political theory, and behavioral sciences which proposes positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions as ways to influence the behavior and decision making of groups or individuals. Nudging contrasts with other ways to achieve compliance, such as education, legislation or enforcement. Nudge has also been referred to as “behavioral insights.”

The first formulation of the term and associated principles was developed in cybernetics by James Wilk before 1995 and described by Brunel University Academic D. J. Stewart as “the art of the nudge” (sometimes referred to as “micronudges”). It also drew on methodological influences from clinical psychotherapy tracing back to Gregory Bateson, including contributions from Milton Erickson, Watzlawick, Weakland and Fisch, and Bill O’Hanlon. In this variant, the nudge is a “microtargetted” design geared towards a specific group of people, irrespective of the scale of intended intervention.

The nudge concept was popularized in the 2008 book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, by two American scholars at the University of Chicago: behavioral economist Richard Thaler and legal scholar Cass Sunstein. It has influenced British and American politicians. Several nudge units exist around the world at the national level (UK, Germany, Japan and others) as well as at the international level (e.g. World Bank, UN, and the European Commission). It is disputed whether “nudge theory” is a recent novel development in behavioral economics or merely a new term for one of many methods for influencing behavior, investigated in the science of behavior analysis.

The book is heavily informed by the Nobel Prize-winning work of psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who demonstrated the existence of cognitive biases. These are systematic errors in thinking that affect the judgments and decisions people make. They are often caused by shortcuts the brain uses, called heuristics, which allow quick thinking but can have a negative impact on behavior. Although the exact mechanism remains unclear, it is thought that nudges can target these cognitive biases and subsequently promote desirable behavior.

The concept involves making simple changes to the choice environment (also called choice architecture) to steer decisions in the right direction. Crucially, nudging never means restricting the available options. Instead, the approach relies on presenting options in a different way. The idea is to redesign choice architecture to gently guide decision makers toward better outcomes.

Thaler and Cass Sunstein’s book refers to influencing behavior without coercion as libertarian paternalism and the influencers as choice architects. They defined their concept as “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.”

One of the most frequently cited examples of a nudge is the etching of the image of a housefly into the men’s room urinals at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, which is intended to “improve the aim”.

The Psychology of Nudging

Because there are many different types of nudges, which can be used in different types of situations, there is no single mechanism that explains how nudges work. However, nudges are generally based on the premise that people are imperfect decision-makers, who display systematic patterns of deviation from rationality, so that by changing people’s choice architecture, which is the context in which they make decisions, it’s possible to influence the decisions that they make.

Specifically, many economic models view people as homo economicus: ideal decision-making machines, with flawless rationality, unlimited cognitive capacity, perfect access to information, and a narrow-range of consistent, self-interested goals. However, nudge theory acknowledges that this model is wrong, since people often act in ways that are not in line with it. As the original book on nudge theory states: “Whether or not they have ever studied economics, many people seem at least implicitly committed to the idea of homo economicus, or economic man—the notion that each of us thinks and chooses unfailingly well, and thus fits within the textbook picture of human beings offered by economists.

If you look at economics textbooks, you will learn that homo economicus can think like Albert Einstein, store as much memory as IBM’s Big Blue, and exercise the willpower of Mahatma Gandhi.

But is the average person like that? Real people have trouble with long division if they don’t have a calculator, sometimes forget their spouse’s birthday, and have a hangover on New Year’s Day. They are not homo economicus;they are homo sapiens.”

Accordingly, nudge theory relies on different models of human cognition, which acknowledge people’s imperfect judgment and decision-making process. The main such model is the dual-process theory, according to which people use two main cognitive systems:

- System 1, which is responsible for intuitive processing, and which is relatively fast, automatic, and effortless

- System 2, which is responsible for conscious reasoning, and which is relatively slow, controlled, and effortful.

Based on this model, people often display irrationality when System 1 generates a faulty intuition and System 2 fails to correct it, or when System 2 fails to engage in proper reasoning. For example, when people are faced with a large number of options to choose from, they might intuitively decide to stick with the default option, even if that’s not the best option, because this saves them from having to analyze all the available options. In this case, the issue is that people rely on System 1 to make a decision that requires the use of System 2. Alternatively, in the same situation, people may try to analyze the options using System 2, but fail to do so correctly due to the large amount of information involved, which could also cause them to pick an option that isn’t the best one for them.

Nudges can be understood through the cognitive system (or systems) that they involve. For example, altering the default option by automatically giving people water with their meal unless they ask for soda is a nudge that generally targets people’s intuition (System 1). Alternatively, informing people about the benefits of saving for their retirement is a nudge that generally targets people’s conscious reasoning (System 2).

Nudges can also be used to address specific systematic patterns of irrationality (called cognitive biases) that people frequently display, as predicted by this and similar models of human cognition. For example, one such bias is the value-action gap, which represents people’s tendency to act in a manner that is inconsistent with their personal values.

In one study, researchers who interviewed people in several countries found that 50%–90% of people said that they favor energy from renewable resources, but only around 3% actually used it, so despite the majority of people setting clean-energy usage as a goal for themselves, few of them took the necessary steps needed in order to pursue this goal. Here, a simple nudge, in the form of changing people’s default contract to one that involves using renewable energy, increased the number of people who use clean energy by approximately 45%, a success that has since been replicated.

Finally, nudges can also take advantage of specific biases and heuristics(mental shortcuts) that people display, in order to influence their choices more effectively. For example, the use of a specific default option as a nudge is often associated with the status quo bias, which represents people’s tendency to prefer to maintain the current state of things.

Overall, nudges work because people are often irrational when making decisions, for example because they tend to rely on intuition when they shouldn’t, which means that they often make imperfect decisions, and that changing various aspects of their environment can prompt them to make better decisions. Nudges can use a variety of mechanisms to achieve this, and generally influence people by targeting their intuition (System 1) or their conscious reasoning (System 2), or both.

Becoming a Nudge Architect

Using nudges to your advantage can be simple if you follow these two principles: For a nudge to be successful, it must (1) decrease the effort required to make the desired choice and (2) improve our motivation to opt for that choice.

One way to nudge yourself toward healthier breakfast habits would be to prepare a nutritious food option the night before. You’d then put it right within eyesight, in a place where even your sleepy-eyed, morning-grumpy self can’t miss it. If a bowl of healthy overnight oats and berries is the first thing you spot when opening the fridge in the morning, the effort of making a good breakfast choice is reduced to near-zero. Furthermore, a pretty food presentation can help to provide that additional motivational boost to choose a healthy breakfast.

Nudges can involve a vast range of different strategies. Another powerful example is the use of defaults. If you have a default breakfast order at your regular coffee shop, and the barista automatically serves you green tea and muesli upon arrival, any changes from the default require effort and become less tempting. A beautifully simple yet oh-so-powerful trick!

You could even rely on modern technology to give you that all-important little nudge toward better decision making. To support a healthy lifestyle, for example, a number of clever fitness apps can make all the difference, as they prompt you to log daily meal choices or track your weight. Similarly, if you are looking to become more active, mobile exercise programs may help to get you going.

Nudge author Richard Thaler famously stated that “just as no building lacks an architecture, so no choice lacks a context”. We need to use this knowledge to our advantage; by taking charge and designing the choice context we need, we can guide our own decision making and produce the choices we want.

Small Nudge, Big Impact

Habit, convenience, and temptation often hamper the most conscientious goals. But behavioral science is showing that those same forces can be rerouted to make fitness and thrift more rewarding than indolence and waste. Amid concerns about rampant obesity, climate change, and aging Baby Boomers with scant retirement savings, psychological scientists are teaming with economists, business leaders, and policymakers to compel people to take better care of themselves, their communities, and the environment.

“We’re helping people to do what they want to do, but never get around to starting — or don’t maintain if they do,” said psychologist Richard Suzman during a forum on psychological science and behavioral economics held in May in Washington, DC. Suzman is director for the Behavioral and Social Research Program at the National Institute on Aging (NIA).

Pioneering this marriage of behavioral science and policymaking is the United Kingdom’s Behavioral Insights Team (BIT) that British Prime Minister David Cameron set up in 2010. Also known as the “nudge” unit, the BIT has found a variety of techniques to cue people to act in their own self-interest, and thus lessen the burden that bad habits place on society. Under the leadership of experimental psychologist and policy expert David Halpern, a former Cambridge University social psychology lecturer, the BIT has conducted a variety of trials to promote good citizenship and healthy behavior, and many of those trials are now being expanded across the UK.

The group found, for example, that sending a personalized text message to people owing court fines results in a 33 percent response rate, compared with a mere 5 percent compliance rate when standard letters are sent. In another trial, the nudge unit documented that job seekers participating in a newly designed program — one that included such features as reduced paperwork and specific job-hunting commitments — were 15 to 20 percent more likely than control subjects to roll off government benefits 13 weeks after signing on. Based on the BIT team’s early successes (its work has boosted income tax collections by £200 million), policymakers and business leaders in the United States and other countries are anxious to adopt similar models.

Hitting the Default Button

Researchers have learned that options and services too often falter because they’re designed to depend on people taking some kind of action. Studies show that relying on inaction yields better results.

Organ donation is one of the most-cited examples. In the United States, 85 percent of Americans say they approve of organ donation, but only 28 percent give their consent to be donors by signing a donor card. The difference means that far more Americans die awaiting transplants.

Eric J. Johnson, a professor at Columbia University Business School, and Daniel Goldstein, an advisor to BIT and a principal researcher at Microsoft Research, found in a 2003 study that in many European countries, individuals are automatically organ donors unless they opt not to be — organ donation is the default choice. In most of these countries, fewer than 1 percent of citizens opt out. In an article published in Science in 2003, Johnson and Goldstein theorized that, among other things, opting out in those countries was simply too much of a hassle for most people, since it involved “filling out forms, making phone calls, and sending mail.”

Harvard economics professor David Laibson, whose research focuses on the psychology of savings and investment, has found that defaults counter workers’ tendencies to delay enrollment in employer-provided retirement plans. The problem with those savings benefits, he says, is that people are beset with present bias, which leads them to avoid thinking about their future. As a consequence, only about half of US employees save sufficient sums for retirement, he says, largely because on average they wait two years to enroll in a 401(k) program. But in one of his studies, he showed that when newly hired workers have to act to “opt out” rather than “opt in” to those savings plans, participation jumped to 85 percent in a year. These findings have sparked the Obama administration to call for employers to enroll workers automatically in retirement plans.

A study by psychological researchers Noah J. Goldstein (University of California, Los Angeles), Robert B. Cialdini (Arizona State University), and Vladas Griskevicius (University of Minnesota) compared the effectiveness of different types of messages in getting hotel guests to reuse their towels rather than send them to the laundry. Messages framed in terms of social norms — “the majority of guests in this room reuse their towels” — were more effective than messages simply emphasizing the environmental benefits of reuse.

Cialdini, has also documented the effectiveness of this persuasion approach as applied to home energy use. In one study, Cialdini’s research team (led by Jessica Nolan and APS Fellow Wesley Schultz at California State University San Marcos) went door to door in a San Diego suburb, placing hangers on doorknobs with messages about energy conservation. For some homes, the signs urged the homeowner to save energy to protect the environment; another said to conserve to benefit future generations; a third pointed to the cost savings that would result; and the last stated that most of the homeowner’s neighbors were taking steps to save energy every day.

At the end of the month, Cialdini and his team returned to the homes to read the meters, and compared them to homes that received no messages at all. Among all those dwellings, the only hanger that made a difference was the one that cited neighbors’ behavior. Homeowners who received any other type of message were no more likely to change their energy usage than control subjects.“People are looking at those around them, like them, in their particular environment, in their particular context, to decide what to do,” Cialdini explains.

Cialdini’s work served as the inspiration for the launch in 2007 of a Virginia-based software company, Opower, which has partnered with more than 75 utilities to incorporate neighbor comparisons into gas and electric bills. According to its website, Opower in 2012 helped consumers save more than $75 million and cut carbon dioxide emissions by 1 billion pounds.

Scientists have also documented this social norm appeal as a potential way to boost voter participation in elections. In two randomized field experiments, Yale University political scientist Alan S. Gerber and psychological scientist Todd Rogers, at Harvard’s Kennedy School, tested two get-out-the-vote scripts in the days prior to the November 2005 general election in New Jersey and the June 2006 primary election in California. One script suggested that voter turnout was expected to be high, while the other forecast the turnout to be low. The call recipients were then asked if they planned to vote. The results showed that the scripts forecasting high voter turnout motivated infrequent or occasional voters to participate in the upcoming elections.

The Health Application

Another concern among US government leaders centers on how people take care of their health. Laura Carstensen of Stanford University studies message framing to promote healthy behavior across the adult life span. She and doctoral student Nanna Notthoff are testing an intervention comparing groups of elderly people who received information about the positive effects of walking with those who were told about the risks of inactivity. Early results have shown that those who were told about the benefits of walking walked more than those who received negative messages about the consequences of inactivity, and that difference is sustained or increased over 30 days.

Influence at Work, a training and consultancy company that Cialdini founded, worked with the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS) in a set of studies aimed at reducing the number of patients who fail to show up for medical appointments. They did this by simply making patients more involved in the appointment-making process, such as asking the patient to write down the details of the appointment themselves rather than simply receiving an appointment card. This reduced the number of wasted appointments by 18 percent. And when the practices participating in the study advertised the number of people who attend their appointments on time, no-shows fell by more than 30 percent.

Behavioral scientists and economists are also identifying the best ways to combat rising levels of overweight and obesity brought on by the rampant availability of cheap, unhealthy, processed foods. Studies have shown that laws requiring calorie postings in restaurant chains is yielding no observable reduction in people’s calorie consumption.

Dan Ariely, professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University, joined a multidisciplinary team in three field experiments that tested an alternative approach: having servers ask customers if they want to downsize portions of three starchy dishes at a Chinese fast-food restaurant. The researchers found that 14 percent to 33 percent of customers accepted the downsizing offer, whether or not they received a discount for the smaller portion, and on average were served 200 fewer calories.

George Loewenstein, a professor of economics and psychology at Carnegie Mellon University, has worked closely with University of Pennsylvania Professor of Medicine Kevin Volpp in research on health incentives. The pair have found that dieters lose more weight when they’re offered cash incentives. In a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the scientists placed adult dieters into three groups — all given the goal of losing 16 pounds in about four months. Participants in one group entered a daily lottery and won money if they hit their weight-loss targets, while those in a second group invested their own money but lost it if they fell short of their goals. A third group received no financial incentive.

Both groups offered the incentives achieved a mean weight loss of more than 13 pounds, with about half the participants reaching the full 16-pound weight-loss goal. The mean weight loss for the control group was just four pounds. While both incentive groups gained some weight back over the next seven months, they fell short of their original weights.

Examples of Nudges

- An example of a nudge is a sign, placed near the door of a room in an office building, which reminds people that they should turn off the light when they leave in order to reduce electricity consumption.

- Another example of a nudge is a reminder, sent to students by their teacher via email, telling them that their class project is due in a week, and that it took past students a week of hard work to complete their own projects.

- Sending people a reminder to schedule a dental check-up doubled the rate of people who signed up.

- Sending students a few personalized text messages helped many of them remember to refile their application for student aid.

- Giving social-media users a reminder about who will be the audience for content that they intend to post helped those users make better decisions regarding what to post and where to post it.

- Using an opt-out system for organ donations, where people are automatically registered as organ donors unless they choose otherwise, instead of an opt-in system, where people have to actively register to become donors, significantly increased the number of people that are registered as organ donors.

- providing feedback to households about their and their neighbors’ electricity usage led people to reduce their energy consumption.

- Making people organ donors by default can increasethe rate of organ donations, compared to requiring people to opt-in in order to become donors.

- Soliciting donations can create a psychological anchor by telling donors that “most people donate $20”, in order to nudge people to donate more money than they would otherwise.

- To encourage people to eat healthier, a cafeteria can place healthy foods in convenient locations and unhealthy food in less convenient locations.

- To encourage people to save more money, a workplace can design relevant forms in a way that visually attracts people’s attention to the available saving program.

- Giving people a simple flyer with information about their employer’s retirement savings plan can lead peopleto contribute more to it.

- f a school wants to reduce the amount of soda that students drink, then placing water bottles instead of soda cans near the register in the cafeteria counts as a nudge, while banning soda outright does not.

- Reminding doctors about the problem of antibiotic resistance in society can reducethe amount of unnecessary antibiotics that they prescribe to patients.

- Sending people a reminder that they need to schedule a doctor’s appointment

- On social media, encouraging people to wait a short while between the moment they submit a post and the time when it’s actually posted can lead peopleto edit and cancel posts that they would have otherwise regretted making public.

- To reduce the amount of soda that you and your family drink, you can make the soda bottles a more difficult option to choose, by placing them at the back of the fridge where they’re inconvenient to reach. Similarly, you can also put a sticker on top of them, with a reminder for you all that you’re trying to drink less soda.

Negative Nudges

A negative nudge is a nudge (a simple aspect of people’s environment that alters their behavior in a predictable way, without forbidding any options or significantly changing their incentives) that prompts people to make a decision that’s bad for them. For example, placing unhealthy snacks near the cash register in a supermarket is a negative nudge, because it prompts people to buy something that’s bad for them.

The difference between positive nudges and negative ones is that positive nudges prompt people to make decisions that are perceived as good for them, while negative nudges prompt people to make decisions that are perceived as bad for them. Either type of nudge may be intentional or unintentional, and in the case of negative nudges, the decision that people are prompted to make may be positive for someone else, such as a company using the nudge to persuade people to buy their low-quality product.

The concept of negative nudges is further illustrated in two examples that are mentioned by behavioral economist Richard Thaler, who refers to negative nudges in this case as sludge: “…the same techniques for nudging can be used for less benevolent purposes. Take the enterprise of marketing goods and services. Firms may encourage buyers in order to maximize profits rather than to improve the buyers’ welfare (think of financier Bernie Madoff who defrauded thousands of investors).

A common example is when firms offer a rebate to customers who buy a product, but then require them to mail in a form, a copy of the receipt, the SKU bar code on the packaging, and so forth. These companies are only offering the illusion of a rebate to the many people like me who never get around to claiming it. Because of such thick sludge, redemption rates for rebates tend to be low, yet the lure of the rebate still can stimulate sales—call it ‘buy bait’.

Public sector sludge also comes in many forms. For example, in the United States, there is a program called the earned income tax credit that is intended to encourage work and transfer income to the working poor. The Internal Revenue Service has all the information necessary to make adjustments for credit claims by any eligible taxpayer who files a tax return. But instead, the rules require people to fill out a form that many eligible taxpayers fail to complete, thus depriving themselves of the subsidy that Congress intended they receive.

Negative nudges often involve changing the ease of choosing a certain option, in one of the following ways:

- By making options that are badfor the target individual easier to choose (i.e. encourage self-defeating behavior). For example, if unhealthy foods are easier to reach in the cafeteria, this encourages people to pick them, despite the fact that they’re unhealthy.

- By making options that are good for the target individual harder to choose (i.e. discourage behavior that’s in a person’s best interests). For example, if registering for a good retirement plan is difficult or requires a large number of inconvenient steps, fewer people are going to do it, despite the fact that it’s beneficial.

Furthermore, negative nudges can involve many of the other mechanisms that are used in positive nudges, such as setting a default option, changing the salience of certain options, and creating a psychological anchor.

Because of the detrimental influence of negative nudges, it’s important to them. Specifically, this can benefit you in several ways:

- It can help you identify situations where you need to remove an existing negative nudge, and potentially replace it with a positive nudge.

- It can help you identify situations where you might be affected by a negative nudge that you can’t remove, so you can account for its influence, for example by using appropriate de-biasing techniques.

- It can help you understand why people act the way that they do in certain situations, predict how they will act in the future, and understand what you need to do in order to change their behavior.

Ethics and Criticisms of Nudging

Nudging has also been criticized. Tammy Boyce, from public health foundation The King’s Fund, has said: “We need to move away from short-term, politically motivated initiatives such as the ‘nudging people’ idea, which are not based on any good evidence and don’t help people make long-term behavior changes.”

Cass Sunstein has responded to critiques at length in his book, The Ethics of Influence: Government in the Age of Behavioral Science making the case in favor of nudging against charges that nudges diminish autonomy, threaten dignity, violate liberties, or reduce welfare. He further defended nudge theory in his Why Nudge?:The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism by arguing that choice architecture is inevitable and that some form of paternalism cannot be avoided. Ethicists have debated nudge theory rigorously. These charges have been made by various participants in the debate who charge nudges for being manipulative, while others question their scientific credibility.

From an ethical perspective, nudging is often viewed as a form of libertarian paternalism (also called soft paternalism). This represents the idea that it’s acceptable and even desirable to influence people’s decisions and actions when this leads them to make decisions that are believed to be better for themselves or for society, as long as they maintain the freedom to make whatever choice they want.

Many of the arguments in favor of nudging revolve around the claim that even though nudges influence people’s decisions, they do so in a manner that preserves people’s ability to choose freely, and around the claim that nudges are impossible to eliminate entirely from the environment, so nudging should be done in an intentional and transparent manner, with people’s best interests in mind.

On the other hand, many of the arguments against nudging revolve around the claim that manipulation of people’s choice is unethical, even if they maintain their freedom of choice, and around the claim that the decision of which direction to nudge people in can involve inherent ethical issues of its own. For example, many criticisms of nudging highlight the use of negative nudges in fields such as marketing and advertising, where nudges are implemented without the intent of helping people make decisions that are necessarily better for them.

In addition, many arguments claim that nudging is not inherently unethical, and depends on factors such as how the nudge was chosen and how it’s implemented. Along those lines, both people who argue in favor and against nudging tend to agree that, if nudges are used, they should be implemented with caution, especially when they are implemented by policymakers on a large scale. Implementing them properly can involve, for example, setting a clear and transparent process for deciding which nudges to implement, which can further involve input from the individuals that it’s meant to influence.

Finally, note that from a practical perspective, many individuals, governments, and organizations are currently using nudges. Furthermore, there is evidence that the citizens of many countries support the use of nudges in general, though there is variation between countries and between individuals with regard to this, and this can also depend on the specific nudge in question.

Overall, from an ethical perspective, there are arguments both in favor and against nudging. Some of these arguments deal with whether or not nudging should be used at all, while others deal with which situations it should be used in and how, especially given that nudges are difficult—if not impossible—to eliminate entirely from people’s decision-making environment.

How to Use Nudges

There are several key things that you should do in order to use nudges as effectively as possible.

First, before using a nudge, you should assess the situation, to consider primarily who the nudge will target and what outcome you want to achieve with it. In doing this, you should also ask yourself whether a nudge is an appropriate solution in your case, from both a practical and an ethical perspective.

Then, you can start designing and using your nudge, while keeping the following in mind:

- The nudge should fit the target audience. For example, you might want to use a different nudge on college students than on elderly people in a retirement home, even if your goal is to get both groups to make a similar decision. This means that you should consider relevant characteristics of your target audience that pertain to nudging, such as their political views and social class, since different nudges can work differently on different types of people.

- The effectiveness of specific nudges depends on the circumstances. Context plays a big role in how effective a nudge is, and just because a certain nudge works well in one case doesn’t meanthat it will also be effective in other situations. As such, you should make sure that the type of nudge that you intend to use is appropriate given the situation in which you intend to use it.

- Small nudges can sometimes be more effective than bigger ones. For example, changing the default option by only a little can sometimes be more effective than changing it drastically, since a major change might antagonize people, which could cause them to avoid that default. At the same time, however, it’s important not to fall into the trap of making nudges so minor that they are rendered ineffective.

Furthermore, there are a few additional guidelines that you should keep in mind when deciding whether and how to present your nudges to others:

- Nudges shouldn’t necessarily be hidden. Nudges can often work even when people are aware of them and of their intended goal, and increased transparency can sometimes make nudges even more effective, in addition to having potential ethical benefits. You can decide on how transparent to make your nudge based on relevant factors such as where and why you’re using it.

- People should perceive the nudge as beneficial. Specifically, you should make sure that the people who are affected by the nudge will feel that the nudge benefits them to a substantial degree.

- People should feel that the nudge respects their ability to choose. Specifically, you should make sure that the people who are affected by the nudge feel that it doesn’teliminate their autonomy and right to choose freely.

- People generally prefer nudges that target their conscious reasoning. Specifically, people generally prefernudges that target their conscious reasoning rather than their intuition, though this depends on the situation, and people may support a nudge even if it targets their intuition.

Overall, to use nudges effectively, you should first determine who the nudge will target and what outcome you want to achieve with it, while considering whether a nudge is an appropriate solution in your case, from both a practical and ethical perspective. Then, you can start designing and implementing the nudge, while keeping in mind, among other things, that the nudge should fit your target audience, that the effectiveness of specific nudges depends on the circumstances, and that small nudges can sometimes be more effective than bigger ones.

How to Respond to Nudges

There are several things that you can do to respond to other people’s use of nudges.

First, you should realize that a given nudge is there, meaning that there’s an aspect of the decision-making environment that prompts people to make a certain decision.

Second, you should assess the nudge, by considering factors such as whether it was intentionally developed by someone, and if so, then why. When doing this, it can help to gather relevant information, and keep in mind relevant principles, such as:

- Cui bono, which is a Latin phrase that means “who benefits?”, and which is used to suggest that there’s a high probability that those responsible for a certain event are the ones who stand to gain from it.

- Hanlon’s razor, which is the adage that you should “never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity”, and which, when applied broadly, suggests that when assessing people’s actions, you should notassume that they acted out of a desire to cause harm, as long as there is a reasonable alternative explanation.

- Parsimony, which is a guiding principle that suggests that all things being equal, you should prefer the simplest possible explanation for a phenomenon or the simplest possible solution to a problem.

It can also help to deconstruct the nudge, in order to figure what it’s supposed to get people to do and through which psychological mechanisms it uses in order to influence them.

Finally, when it comes to responding to the use of nudges directly, there are several main courses of action you can choose from, based on factors such as the circumstances and your personal goals:

- Accept the nudge, if you believe that doing so is beneficial, which may very well be the case in many situations.

- Reduce the influence that the nudge has, by using appropriate de-biasing techniquesyourself, or by encouraging their use by relevant individuals.

- Ask the individual or group who implemented the nudge why they’re doing it.

- Mention the nudge, either publicly or privately, to whoever implemented it or to the people who are being nudged.

- Eliminate the nudge, or replace it with an alternative nudge.

- Take the use of the nudge into account, for example when understanding the type of behavior that someone is willing to engage in to influence others, but do nothing about it directly.

Note that although it may be beneficial to engage in all of the steps outlined here, it’s not always necessary to do so in order to respond to nudges effectively. For example, before making an important decision, you might decide to simply use relevant de-biasing techniques, such as slowing down your reasoning process and making it explicit, even without identifying the specific nudges that may be influencing your thinking.

Overall, to respond to a nudge, you should realize that it’s in effect, assess it, and then either accept it, ask the responsible individual about it, call out its use, eliminate it, use de-biasing techniques to reduce its influence, or take it into account without doing anything about it directly.

Summary and conclusions

- A nudge is a simple aspect of people’s decision-making environment that alters their behavior in a predictable way, without forbidding any options or significantly changing their incentives.

- Examples of nudges include sending people a reminder to schedule a doctor’s appointment, ensuring that healthier food is more noticeable in a cafeteria, providing people with information regarding how much electricity they use, and reminding people what audience will see what they’re about to post on social media.

- Common types of nudges include setting a default option, creating a psychological anchor, changing the ease of choosing certain options, changing the salience of certain options, informing people of something, reminding people of information they already know, reminding people to do something, and getting people to slow down.

- To use nudges, start by determining who the nudge will target and what outcome you want to achieve with it, while considering whether a nudge is an appropriate solution; then, design and implement the nudge, while remembering that the nudge should fit your target audience, that the effectiveness of specific nudges depends on the circumstances, and that small nudges can sometimes be more effective than bigger ones.

- To respond to a nudge, you should realize that it’s in effect, assess it, and then either accept it, ask the responsible individual about it, call out its use, eliminate it, use debiasing techniques to reduce its influence, or take it into account without doing anything about it directly.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book:I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.