By Ray Williams

May 19, 2020

Part 1: The Rise of Authoritarianism and Decline of Democracy in America

“ First they cam for the Jews, and I did not speak out because I was not a Jew. Then they came for the Communists and I did not speak out because I was not a Communist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for me and there was no one left to speak out for me.”—Pastor Martin Niemoller.

There are disturbing signs that America’s strength as a democracy has weakened as reflected in significant support for authoritarianism and an autocratic President. And while we think of autocratic states and dictatorships developing as a result of a sudden and often violent revolution, they can evolve slowly, with the changes often either going without notice, or not being serious enough for concerted citizen action.

Several political experts, citing evidence, have sounded an alarm about the erosion of democracy and a few even suggest the existence of similarities to Fascism in history. In a sense, there is a bitter irony here, if their perspectives are accurate, as America has long been recognized as the world’s earliest and strongest democracy.

Some Distinctions

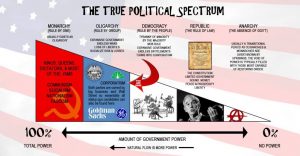

An autocracy is a system of government in which supreme power is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are not subject to external legal restraints nor the control of the populace. Absolute monarchies (such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Brunei and Swaziland) and dictatorships (such as Turkmenistan, Russia and North Korea) are the main modern-day forms of autocracy.

In our earlier history the term “autocrat” was coined as a favorable feature of the ruler, having some connection to the concept of “lack of conflicts of interests” as well as an indication of grandeur and power. The Russian Tsar for example was styled, “Autocrat of all the Russias”, as late as the early 20th century.

Authoritarianism and Totalitarianism are levels of power that the government wields over the private lives of individual citizens. An authoritarian regime will exercise some power over people’s private lives, but it does not control everything. Tito’s Yugoslavia and Fascist Italy were good examples of authoritarian regimes.

Totalitarianism exists when the government seizes total, or near total control over every living being and knows everything about their private lives. Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union and today’s North Korea are good examples of totalitarian regimes.

Fascism is a counter to Socialism and Communism, but is not based on any singular philosophy. In general, Fascist movements preach in favor of militarism, extreme nationalism, anti-communism, and anti-social change. Some, like the Nazis, also added racial purity as another major cause for Fascism to support, which many times has earned the term “Nazism” to differentiate itself from Mussolini’s Italy. Fascism is on the far fringes of the political Right. Nazi Germany, Franco’s Spain, and Mussolini’s Italy are the best examples of Fascist governments.

Hitlerism is a term applied by the Western Allies to anyone who agreed with Nazi Party racial theory and Nazi Party policies, largely because Hitler was the leader of the Nazi Party and was at war with the Allied Powers.

Both totalitarianism and military dictatorship are often identified with, but need not be, an autocracy. Totalitarianism can be headed by a supreme leader, making it autocratic, but it can also have a collective leadership such as a commune, junta, or single political party.

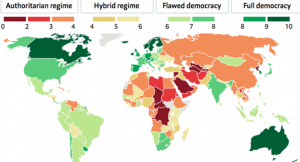

The Decline of Democracies Globally

In 2018, Freedom in the World recorded the 13th consecutive year of decline in global freedom. The reversal has spanned a variety of countries in every region, from long-standing democracies like the United States to consolidated authoritarian regimes like China and Russia. The overall losses are still shallow compared with the gains of the late 20th century, but the pattern is consistent and ominous. Democracy is in retreat. Of the 41 countries that were consistently ranked Free from 1985 to 2005, 22 have registered net score declines in the last five years.

In countries that were already authoritarian, governments have increasingly shed the thin façade of democratic practice that they established in previous decades, when international incentives and pressure for reform were stronger. More authoritarian powers are now banning opposition groups or jailing their leaders, dispensing with term limits, and tightening the screws on any independent media that remain.

Meanwhile, many countries that democratized after the end of the Cold War have regressed in the face of rampant corruption, anti-liberal populist movements, and breakdowns in the rule of law. Most troublingly, even long-standing democracies have been shaken by populist political forces that reject basic principles like the separation of powers and target minorities for discriminatory treatment.

So far it has been anti-liberal populist movements of the far right are hostile to immigration, and reject constitutional checks on the will of the majority have been most effective at seizing the open political space. In countries from Italy to Sweden, anti-liberal politicians have shifted the terms of debate and won elections by promoting an exclusionary national identity as a means for frustrated majorities to gird themselves against a changing global and domestic order.

By building alliances with or outright capturing mainstream parties on the right, anti-liberals have been able to launch attacks on the institutions designed to protect minorities against abuses and prevent monopolization of power. Victories for anti-liberal movements in Europe and the United States in recent years have emboldened their counterparts around the world, as seen most recently in the election of Jair Bolsonaro as president of Brazil.

These movements damage democracies internally through their dismissive attitude toward fundamental civil and political rights, and they weaken the cause of democracy around the world with their unilateralist reflexes. For example, anti-liberal leaders’ attacks on the media have contributed to increasing polarization of the press, including political control over state broadcasters, and to growing physical threats against journalists in their countries. At the same time, such attacks have provided cover for authoritarian leaders abroad, who now commonly cry “fake news” when squelching critical coverage.

Only a united front among the world’s democratic nations—and a defense of democracy as a universal right rather than the historical inheritance of a few Western societies—can roll back the world’s current authoritarian and anti-liberal trends. By contrast, a withdrawal of the United States from global engagement on behalf of democracy, and a shift to transactional or mercenary relations with allies and rivals alike, will only accelerate the decline of democratic norms.

There should be no illusions about what the deterioration of established democracies could mean for the cause of freedom globally. Neither America nor its most powerful allies have ever been perfect models—the United States ranks behind 51 of the 87 Free countries in Freedom in the World analysis.

That major democracies are now flagging in their efforts, or even working in the opposite direction, is cause for real alarm.The truth is that democracy needs defending, and as traditional champions like the United States stumble, core democratic norms meant to ensure peace, prosperity, and freedom for all people are under serious threat around the world.

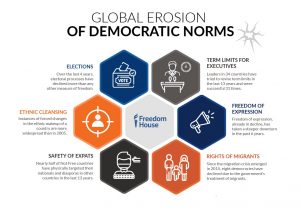

For example, elections are being corrupted as autocracies find ways to control their results while sustaining a veneer of “competitive” balloting. Polls in which the outcome is shaped by coercion, fraud, gerrymandering, or other manipulation are increasingly common. Freedom House’s indicators for elections have declined at twice the rate of overall score totals globally during the last three years.

In a related phenomenon, the principle of term limits for executives, which have a long provenance in democracies but spread around the world after the end of the Cold War, is weakening. According to Freedom House’s data, leaders in 34 countries have tried to revise term limits—and have been successful 31 times—since the 13-year global decline began.

Freedom in the World data show freedom of expression declining each year over the last 13 years, with sharper drops since 2012. This year, press freedom scores fell in four out of six regions in the world.

The offensive against freedom of expression is being supercharged by a new and more effective form of digital authoritarianismanchored in the Internet. As documented in Freedom House’s most recent Freedom on the Net report, China is now exporting its model of comprehensive internet censorship and surveillance around the world, offering trainings, seminars, and study trips as well as advanced equipment that takes advantage of artificial intelligence and facial recognition technologies. As the internet takes on the role of a virtual public sphere, and as the cost of sophisticated surveillance declines, Beijing’s desire and capacity to spread totalitarian models of digitally enabled social control pose a major risk to democracy worldwide. Russia is quickly planning to institute changes that mirror those actions.

Another norm under siege in authoritarian states is protection of the rights of migrants and refugees, including the rights to due process, to freedom from discrimination, and to seek asylum. All countries have the legitimate authority to regulate migration, but they must do so in line with international human rights standards and without violating the fundamental principles of justice provided by their own laws and constitutions. Anti-liberal populist leaders have increasingly demonized immigrants and asylum seekers and targeted them for discriminatory treatment, often using them as scapegoats to marginalize any political opponents who come to their defense.

In the Freedom in the World report, eight democracies have suffered score declines in the past four years alone due to their treatment of migrants. With some 257 million people estimated to be in migration around the world, the persistent assault on the rights of migrants is a significant threat to human rights and a potential catalyst for other attacks on democratic safeguards.

Freedom House’s global survey shows that ethnic cleansing is a growing trend In Syria and Myanmar, hundreds of thousands of civilians from certain ethnic and religious groups have been killed or displaced as world powers either fail to respond adequately or facilitate the violence. Russia’s occupation of Crimea has included targeted repression of Crimean Tatars and those who insist on maintaining their Ukrainian identity. China’s has moved to mass internment of Uighurs and other Muslims—with some 800,000 to 2 million people.

The Democracy Index 2016, released in January 2017, now lists the United States as a flawed democracy. The basis for the decline was not the most recent presidential election. Instead, the report argues that Donald Trump benefited from a lack of popular trust in American government, a lack that also led to the demotion. Indeed, the ranking of the United States had been dropping for a number of years; the country was just barely included at the bottom of the list of fully functioning democracies in 2015.

In his 2014 essay, “America in Decay,” conservative political scientist Francis Fukuyama analyzed that processes that have contributed to the decay of democracy in the United States. In particular, he identified the distribution of power as one of the main contributing factors. Fukuyama wrote that: “Liberal democracy is almost universally associated with market economies, which tend to produce winners and losers and amplify what James Madison termed the “different and unequal faculties of acquiring property.”

In 2016, candidates running for federal office spent a record $6.4 billion on their campaigns, while lobbyists spent $3.15 billion to influence the government in Washington. Both sums are twice that of 2000 levels. This reality sparked former president Jimmy Carter to lament that any candidate to the Presidency of the United States needs at least 200 million dollars to set foot on the path to the White House. “There’s no way now for you to get a Democratic or Republican nomination without being able to raise $200 or $300 million or more,” Carter told Oprah Winfrey on her talk show in September 2015.

Looking at the most recent nationwide elections in each OECD nation, the U.S. placed 26th out of 32 in terms of election turnouts. The highest turnout rates among OECD nations were in Belgium (87.2%), Sweden (82.6%) and Denmark (80.3%). One factor behind Belgium’s high turnout rates – between 83% and 95% of VAP in every election for the past four decades – may be that it is one of the 24 nations around the world (and six in the OECD) with some form of compulsory voting.

In 2011, when Newsweek administered the United States Citizenship Test to over 1000 American citizens, 38% of Americans failed. This widespread civic illiteracy is not just concerning, it is dangerous. How can people expect to hold their representatives accountable when 61% don’t know which party controls the House and 77% can’t name either of their state’s senators? How can Americans expect to exercise their rights when over one third can’t name any of the five rights protected by the First Amendment (freedom of speech, religion, the press, protest, and petition)?

Partisan gerrymandering is commonly used to increase the power of a political party. In some instances, political parties collude to protect incumbents by engaging in bipartisan gerrymandering. After racial minorities were enfranchised, some jurisdictions engaged in racial gerrymandering to weaken the political power of racial minority voters, while others engaged in racial gerrymandering to strengthen the power of minority voters.

According a major bipartisan poll that commissioned by the George W. Bush Institute, the University of Pennsylvania’s Biden Center and Freedom House, which tracks the vitality of democracies around the world. The three groups have partnered to create the Democracy Project, with the goal of monitoring the health of the American system, 50% of Americans think the United States is in “real danger of becoming a non- democratic, authoritarian country.” A majority, 55 percent, see democracy as “weak” – and 68 percent believe it is “getting weaker.” Eighty per cent of Americans say they are either “very” or “somewhat” concerned about the condition of democracy.

The Growth of Authoritarianism in America

Research conducted by Bright Line Watch, the group that organized the Yale conference on democracy, shows that Americans are not as committed to democracy as you might expect. Another startling finding is that many Americans are open to “alternatives” to democracy. In 1995, for example, one in 16 Americans supported Army rule; in 2014, that number increased to one in six. According to another survey cited at the Yale conference, 18 percent of Americans think a military-led government is a “fairly good” idea.

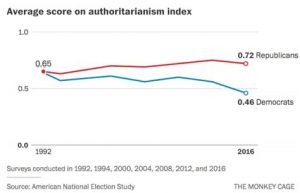

Remaking Partisan Politics through Authoritarian Sorting, a book by political scientists Christopher Federico, Stanley Feldman and Christopher Weber examines authoritarianism in America. The authors found that in 1992, 62 percent of white voters who ranked highest on the authoritarian scale supported George H.W. Bush. In 2016, 86 percent of the most authoritarian white voters backed Trump, an increase of 24 percentage points.

Federico, writing with Christopher Johnston of Duke and Howard G. Lavine of the University of Minnesota, published “Open versus Closed: Personality, Identity, and the Politics of Redistribution,” which also explores the concept of authoritarian voting. Johnston argues “Over the last few decades, party allegiances have become increasingly tied to a core dimension of personality we call ‘openness.’”

Citizens high in openness value independence, self-direction, and novelty, while those low in openness value social cohesion, certainty, and security. Individual differences in openness seem to underpin many social and cultural disputes, including debates over the value of racial, ethnic, and cultural diversity, law and order, and traditional values and social norms.

Johnston notes that personality traits like closed mindedness, along with aversion to change and discomfort with diversity, are linked to authoritarianism: “As these social and cultural conflicts have become a bigger part of our political debates, citizens have sorted into different parties based on personality, with citizens high in openness much more likely to be liberals and Democrats than those low in openness who are more likely to be conservatives and Republican.”

Karen Stenner’s seminal book The Authoritarian Dynamic describes how authoritarianism has grown more rapidly and in greater force than anyone had imagined, in the personage of Donald Trump and his norm-shattering rise.

According to Stenner’s theory, there is a certain subset of people who hold latent authoritarian tendencies. These tendencies can be triggered or “activated” by the perception of physical threats or by destabilizing social change, leading those individuals to desire policies and leaders that we might more colloquially call authoritarian.

Authoritarians prioritize social order and hierarchies, which brings, for them, a sense of control to a chaotic world. Challenges to that order — diversity, influx of outsiders, breakdown of the old order — are experienced as personally threatening because they risk upending the status quo order people equate with basic security.

Authoritarianism experts agree on the basic causality of authoritarianism. People do not support extreme policies and strongman leaders just out of an affirmative desire for authoritarianism, but rather as a response to experiencing certain kinds of threats.

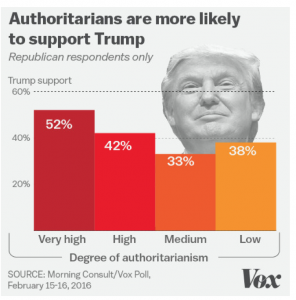

Amanda Tauba, writing in Vox, conducted a survey the results of which prompted her to argue the following: “The first thing that jumped out from the data on authoritarians is just how many there are. Our results found that 44 percent of white respondents nationwide scored as ‘high’ or ‘very high’ authoritarians, with 19 percent as ‘very high.’ That’s actually not unusual, and lines up with previous national surveys that found that the authoritarian disposition is far from rare. The key thing to understand is that authoritarianism is often latent; people in this 44 percent only vote or otherwise act as authoritarians once triggered by some perceived threat, physical or social.”

According to the survey, authoritarians skew heavily Republican. More than 65 percent of people who scored highest on the authoritarianism questions were GOP voters. More than 55 percent of surveyed Republicans scored as “high” or “very high” authoritarians. And at the other end of the scale, that pattern reversed. People whose scores were most non-authoritarian — meaning they always chose the non-authoritarian parenting answer — were almost 75 percent Democrats.

Authoritarians generally and Trump voters specifically, explains Tauba, are highly likely to support five policies:

- Using military force over diplomacy against countries that threaten the United States.

- Changing the Constitution to bar citizenship for children of illegal immigrants.

- Imposing extra airport checks on passengers who appear to be of Middle Eastern descent in order to curb terrorism.

- Requiring all citizens to carry a national ID card at all times to show to a police officer on request, to curb terrorism.

- Allowing the federal government to scan all phone calls for calls to any number linked to terrorism.

What these policies share in common is an outsized fear of threats–physical and social, and, more than that, a desire to meet those threats with severe government action — with policies that are authoritarian not just in style but in actuality.

“Any attempt to appraise the chances of a fascist triumph in America,” wrote Theodor W. Adorno and his colleagues at the start of their classic 1950 study The Authoritarian Personality, “must reckon with the potential existing in the character of the people.” Adorno says “authoritarianism in America has a long and dark history that includes not just the witch-hunts fueling McCarthyism, with its paranoid focus on treason and ‘subversives’ in the federal government, but—very much related—how far-Right groups such as the Committee for Constitutional Government, Facts Forum, and National Committee for the Preservation of Americanism, taking succor from that extremism, exerted profound influence on the nation’s reactive forces before they were exposed as part of ‘the Nazi Underworld of America.’”

About that potential and its vulnerability to manipulation and worse, Adorno and his colleagues were far from optimistic. Their study, involving thousands of Americans from diverse backgrounds with varied incomes, helped produce an “F-scale” to measure receptivity to fascistic and other antidemocratic forces. Among its still-valid criteria were “conventionalism” (summed up by the statement, “Lax morals and wayward habits are ruining our country”); “authoritarian submission” (“Our country desperately needs a mighty leader”); and “authoritarian aggression” (“We need a leader who will destroy the things perceived as ruining our country”).

Adorno and his colleagues looked specifically at Americans’ reaction to Jewish refugees fleeing persecution and genocide in Nazi Germany to determine whether mainstream Americans might be receptive to far-Right propaganda. As today, with proposed but unlawful travel bans against nationals fleeing war-torn countries and ICE raids enabling rapid deportation, immigration was at the time a weathervane—an indicator of its citizens’ attitudes and propensities.

The Authoritarian Personality examined the attitudes of Americans who “would readily accept fascism if it should become a strong or respectable social movement”—of the kind represented, say, by a sitting president. What distinguished it as a study was its willingness to assess how “individuals differ in their susceptibility to antidemocratic propaganda, in their readiness to exhibit antidemocratic tendencies.”

Authoritarians use “gaslighting” to manipulate and control other people. The term gaslighting comes from the 1930s play Gas Light and the 1940s Hollywood movie version (Gaslight) in which a manipulative husband tries to unmoor his wife, played by Ingrid Bergman, by tampering with her perception of reality. He dims the gaslights and then pretends it’s only she who thinks they are flickering as the rooms grow darker…. He [looks to] exert power and control by creating doubts about what is real and what isn’t. Gaslighting was a feature of “Big Brother,” in George Orwell’s classic 1984,a scathing critique of authoritarianism, where facts, opinions, conspiracies, and fabrications are all interchangeable. In Orwell’s dystopia, the state issues decrees insisting “Freedom is Slavery,” “Ignorance is Strength,” “War is Peace,” and “2 + 2 = 5.”

The Authoritarian Personalityunderscores why political “gaslighting”—a variety of truth-blurring techniques designed to confuse voters and control citizens—came to be favored by strongmen and authoritarians alike. Gaslighting augments their power when trust is widely perceived as faulty and missing, especially when there is polarization.

In their research study, Research, Ethics and Risk in the Authoritarian Field, Dutch political scientist Marlies Glasium and his colleagues encourage us to devote less attention to focusing on authoritarian regimes such as those in Russia and Turkey and Saudi Arabia, and more on the authoritarian practices and behaviors that could occur in any country, including the U.S.

Glasius defines authoritarian practices as “actions … sabotaging accountability to people over whom a political actor exerts control, or their representatives, by disabling their access to information and/or disabling their voice.” For example, voter suppression, minority scapegoating and harassment, withholding important information from the other branches of government and the free press, digital surveillance, manipulating and corrupting the country’s financial system for personal gain and using government institutions and apparatus to centralize power.

Marc Hetherington at Vanderbilt University and Jonathan Weiler at the University of North Carolina, published a book, Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics, in which they argue that the major cause of the polarization of American politics was not just gerrymandering and money in politics, but a large and powerful electoral group—authoritarians. They argue that the GOP, by positioning itself as the party of traditional values and law and order had unknowingly attracted out a vast population of Americans with authoritarian tendencies. This trend, they contend, has been accelerated in recent years by demographic and economic changes such as immigration, leading these authoritarians to seek out a strongman leader who would preserve as status quo and impose order on a world they perceive as increasingly alien.

For years now, before anyone thought a person like Donald Trump could possibly lead a presidential primary, a small but respected niche of academic research has been laboring over a question, part political science and part psychology, that had captivated political scientists since the rise of the Nazis.

Karen Stenner, author of The Authoritarian Dynamic, argues there is a certain subset of people who hold latent authoritarian tendencies that can be triggered by the perception of physical threats or social changes outside their control. This is a time of social change in America. The country is becoming more diverse, which means that many white Americans are confronting race in a way they have never had to before. Those changes have been happening for a long time, but in recent years they have become more visible and harder to ignore. And they are coinciding with economic trends that have squeezed working-class white people.

As NYU professor Jonathan Haidt has written, a trigger is activated that says, “In case of moral threat, lock down the borders, kick out those who are different, and punish those who are morally deviant.”

Hetherington and American University professor Elizabeth Suhay foundthat when non-authoritarians feel sufficiently scared, they also start to behave, politically, like authoritarians. But Hetherington and Suhay found a distinction between physical threats such as terrorism, which could lead non-authoritarians to behave like authoritarians, and more abstract social threats, such as eroding social norms or demographic changes, which do not have that effect. That distinction would turn out to be important, as it meant that in times when many Americans perceived imminent physical threats, the population of authoritarians swells rapidly.

But the research on authoritarianism suggests it’s not just physical threats driving all this. There is another kind of threat — larger, slower, less obvious, but potentially even more powerful — pushing authoritarians to these extremes: the threat of social change. This could come in the form of evolving social norms, such as the erosion of traditional gender roles or how to discuss sexual orientation. It could come in the form of rising diversity, whether that means demographic changes from immigration or merely changes in the colors of the faces on TV. Or it could be any changes, political or economic, that disrupt social hierarchies.

What these changes have in common is that, to authoritarians, they threaten to take away the status quo as they know it — familiar, orderly, secure — and replace it with something that feels scary because it is different and destabilizing, but also sometimes because it upends their own place in society. According to the literature, authoritarians will seek, in response, a strong leader who promises to suppress the scary changes, if necessary by force, and to preserve the status quo.

The Psychology of Authoritarianism

New psychology research provides evidence that Republicans tend to have slightly morepsychopathic personality traits compared to Democrats.“Psychopathic traits with their associated empathy deficits appear relevant to the discussion of political attitudes and political candidates,” wrote the authors of the study, which was published in the journal Personality and Individual Differences.

The researchers found that psychopathic boldness and meanness tended to be higher in Republicans compared to Democrats. In other words, Republicans were more likely to agree with statements such as “I don’t mind if someone I dislike gets hurt”, “I taunt people just to stir things up,” “I can get over things that would traumatize others,” and “I never worry about making a fool of myself with others.”

The researchers also found that boldness was associated with conservative opinions on economic issues, while meanness was associated with conservative opinions on social issues. Boldness was linked to opposition to government spending, immigration, and gay rights. Meanness was associated with opposition to universal healthcare, marijuana legalization, equal pay for women, and affirmative action.

The new study builds on previous research, published in 2013 and 2014, which found that psychopathic traits tended to be higher among political conservatives.

“Considering the political success of presidential candidates with higher levels of psychopathic traits (i.e., fearless dominance) in the US, it may be surmised that popular political candidates championing conservative opinions (e.g., restricting free speech and immigration, decreasing gun control and taxation) may possess elevated psychopathic traits,” the authors of the study concluded.

The Militarization of the Authoritarian State

Authoritarian/autocratic states often are characterized by militarism. The U.S. has been virtually continuously at war since the end of WWII, and its military is the largest and most powerful in the world, consuming a substantial part of the federal budget.

Yet there are also signs that militarization has occurred internally.

According to journalist Todd Miller, author of Storming the Wall: Climate Change, Migration, and Homeland Security “the once thin borderline of the American past” is “an ever-thickening band, now extending 100 miles inland around the United States—along the 2,000-mile southern border, the 4,000-mile northern border and both coasts… This ‘border’ region now covers places where two-thirds of the US population (197.4 million people) live… The ‘border’ has by now devoured the full states of Maine and Florida and much of Michigan.”

As part of its so-called efforts to keep the nation safe from a host of threats, the U.S. government has declared that ever-expanding border region a “Constitution-free zone.” Miller explains: “In these vast domains, Homeland Security authorities can institute roving patrols with broad, extra-constitutional powers backed by national security, immigration enforcement and drug interdiction mandates.

There, the Border Patrol can set up traffic checkpoints and fly surveillance drones overhead with high-powered cameras and radar that can track your movements. Within twenty-five miles of the international boundary, CBP agents can enter a person’s private property without a warrant.”

According to federal statutes, regulations, and court decisions, CBP officers have the authority to question and detain, without a warrant, any person trying to gain entry into the country and seize their belongings. CBP can also question individuals about their citizenship or immigration status and ask for documents that prove admissibility into the country. And finally CBP officers can arrest and detail individuals for up to 14 days without filing a charge against them.

The Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency, which is an arm of the Department of Homeland Security, made up of more than 60,000 Customs and Border Protection employees, and supplemented by the National Guard and the U.S. military. Government agents continue to roam further afield of the so-called border as part of their so-called crackdown on illegal immigration, drugs and trafficking. Consequently, greater numbers of Americans are being subject to warrantless searches, ID checkpoints, transportation checks, and even surveillance on private property.

In addition, America’s police forces—which look like, dress like, and act like the military— have undeniably become a “standing” or permanent army, one composed of full-time professional soldiers who do not disband, which is exactly what the American Founders feared. With the police increasingly posing as pseudo-military forces—complete with weapons, uniforms, assault vehicles, etc.—a good case could be made for the fact that SWAT team raids, which break down the barrier between public and private property, have done away with this critical safeguard.

The third largest federal agency after the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Defense is the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). It has 240,000 full-time workers, $40 billion budget and sub-agencies that include the Coast Guard, Customs and Border Protection, Secret Service, Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The DHS now extends its tentacles into every aspect of American life.

Many questionably legal and ethical government actions can be traced back to the DHS–its police state mindset and the billions of dollars it distributes to police agencies in the form of grants to transform them into extensions of the military– militarizing police; incentivizing SWAT teams; spying on protesters; stockpiling ammunition; distributing license plate readers to police agencies; contracting to build detention camps; tracking cell-phones with Stingray devices; carrying out military drills and lockdowns in American cities; using the TSA to carry out soft target checkpoints; directing government workers to spy on Americans; conducting widespread spying networks using fusion centers; utilizing drones and other spybots on civilians; funding city-wide surveillance cameras; and carrying out Constitution free border control searches.

The Rise of Populism

Authoritarian populism is a significant challenge to democratic politics on both sides of the Atlantic. An increasing number of extreme populist politicians are making headway across the world’s established democracies.

Western societies, including the United States, are becoming more diverse, especially in urban centers. Cosmopolitan urban centers, such as the metropolitan areas on the East and West Coasts, are seeing concentrations of economic dynamism, growth, and new opportunities. Combining diversity, openness, and economic dynamism, cities have grown into an economic and cultural antithesis of the less diverse and economically stagnant suburban and rural areas.

In the U.S. context, the rise of authoritarian populism has gone hand in hand with the decline of trust in government and political institutions; the decline in lawmakers’ responsiveness to the public’s expressed policy preferences; and the rise of ideological polarization. Taken together, these should be seen as warning signs of the declining strength of America’s democracy.

The decline of trust in the U.S. government dates back to the mid-1960s. Fifty years ago, close to three-quarters of the U.S. population trusted the federal government; that number has dropped to below 25 percent. During the first year of the Trump administration, this decline has continued. A similar erosion of trust can be seen in other areas of U.S. society— such as media, churches, corporations, and universities. This makes it difficult to see the decline of political trust as an isolated phenomenon. Furthermore, in some situations, low levels of trust in government could be benign. Citizens who are distrustful and scrutinizing, for example, might be in a better position to hold elected representatives accountable than citizens who hold a more romantic view of politics and politicians.

Cas Mudde, a Dutch political scientist, wrote in a 2015 column for The Guardianthat “populism is an illiberal democratic response to undemocratic liberalism.” This is why Kurt Weyland, a University of Texas political scientist, wrote, in a 2013 academic article, “Populism will always stand in tension with democracy.”

Populism is spreading across the globe. In Europe, populist parties have won victories in Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Slovakia, and Switzerland; and they have joined governing coalitions in Finland, Norway, and Lithuania. More broadly, strongmen with populist agendas have become president — including Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and Donald Trump in the United States.

Various causes lie behind populist upsurges, ranging from increased economic hardship and inequality to growing frustrations with globalization and immigration. But the consequences are worrisome, because research suggests the very real possibility of democratic backsliding worldwide. Populist takeovers are associated with dictatorships and the dismantling of democratic institutions.

Contemporary populists share the objectives of their historical predecessors in Latin America and Europe. They promote a disdain for traditional political institutions, praise the advantages of strong and decisive leadership, and vocalize deep distrust of experts and the “establishment.” Today’s populists use new tactics, however. They no longer signal a quick break from democracy, but rather set in motion a subtle chipping away at democratic institutions.

Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan illustrate this dynamic. Rather than gaining control through coup or revolution, which can incite domestic and international pushback, these leaders came to power via elections. Once in office, they stoked widespread discontent to undermine institutional constraints on their power, sideline the opposition, and weaken civil society. The tactics used are straightforward and subtle enough each step of the way to make it hard for supporters of democracy to take strong oppositional action.

Populist regimes place loyalists and allies in key positions regardless of competence, especially in the judiciary and security services. Traditional media is muzzled, and government turns to alternative outlets to push its message.

Those in power use lawsuits and new legislation to undermine civil society and the opposition. Today’s populist tactics represent a shift in how democracies fall apart.

“Authoritarianization” is the term for the kind of regime change where elected leaders lead the way in undermining democratic institutions. Historically, military coups were the dominant pathway. Data on authoritarian regimes show that from 1946 to 1999, 64 percent of the democracies that collapsed into authoritarianism did so as the result of coups. From2000 to 2010, however, authoritarianization has been on the rise, representing 40 percent of all democratic failures, equal to the percentage of failures through coups. All signs point to populist-fueled authoritarianization becoming the most common pathway from democracy to autocracy.

Not only are we seeing a change in how democracies wane; a new type of dictatorship is emerging. Populist politics gives rise to “personalist dictatorships,” where power is concentrated in the hands of a single individual. From 2000 to 2010, this happened in 75%of authoritarian transitions, compared to 50% of such transitions from1946 to 1999. We have seen this personalist route from election to authoritarianism in Russia, Turkey, and Venezuela, as well as in Peru under Alberto Fujimori. Even where populist strongmen have not fully dismantled democracy, we often see them enjoying a disproportionate share of power, as in Nicaragua under Daniel Ortega, Ecuador under Rafael Correa, Hungary under Viktor Orban, and Poland under Jaroslaw Kaczynski.

Growing literature in political science finds that personalist dictatorship is associated with a wide range of ruinous outcomes. Even compared to other kinds of dictatorships, personalist regimes pursue the riskiest and most aggressive foreign policies. They are the most likely to invest in nuclear weapons, initiate interstate conflicts, and launch wars against democracies. Weakened accountability mechanisms enable personalist leaders to take risks without facing consequences for poor choices. This is more the case for personalist regimes than even for other types of authoritarian regimes. Cases in point include the adventurism of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, of Idi Amin in Uganda, and of the Kim family in North Korea. The annexation of Crimea by Russia’s Vladimir Putin is another prominent example.

Existing research also shows that personalist dictatorships stoke xenophobic sentiments and mismanage foreign aid allocations. And when such regimes collapse, they are unlikely to revert to democracy. In short, populist-fueled creeping authoritarianism is potentially triggering a global spread of highly adventurist and dangerous regimes. Conditions giving rise to populist candidates and parties are probably not going to disappear in the near future. Problematic trends include slow growth and rising economic inequalities and joblessness; rising frustrations with immigration and refugee crises; and citizen perceptions that traditional political establishments are crooked and corrupt. In combination, such trends may very well continue fuel support for populist leaders worldwide, putting elected strongmen in position to shift democracies in authoritarian directions.

Pushing back against this threat to democracy will be difficult to accomplish precisely because of the subtle means through which today’s populists implement strongman rule. Because they incrementally dismantle democratic institutions and norms, no single dramatic change triggers widespread mobilization of opposition. All too often, populist leaders can frame vocal critics as destabilizing provocateurs, fragmenting resistance and rendering it ineffective. In short, the global surge in populism poses a serious challenge to democracy. A first step toward mitigating this threat is for citizens and leaders in many countries to recognize what is occurring and how.

Be sure to read Part 2 of this article, “Is America Becoming an Autocracy Under President Trump?”

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself and Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go,available in paperback and ebook on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.