If you think you’re hearing the word “empathy” everywhere, you’re right. It’s gone beyond the discussions by researchers and psychologists into the boardrooms of business and schools and politics. And we’ve seen ample examples of empathy expressed from Ukraine to COVID and climate change tragedies.

Is the world suffering from an empathy deficit? According to a 2011 meta-analysis led by social psychologist Sara Konrath, empathic concern and perspective-taking have declined since 1979, with a particularly steep drop occurring since 2000.

With the recent increase in focus on racial injustice, economic inequality and political polarization, empathy deficit or not—the world can benefit from an improved capacity to understand different perspectives. The very fact that you want to learn how to be more empathetic should be cause for hope.

What is Empathy?

But what is empathy? It’s the ability to step into the shoes of another person, aiming to understand their feelings and perspectives, and to use that understanding to guide our actions. That makes it different from kindness or pity or sympathy. And don’t confuse it with the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” As George Bernard Shaw pointed out, “Do not do unto others as you would have them do unto you—they might have different tastes.”

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), empathy is “understanding a person from his or her frame of reference rather than one’s own, or vicariously experiencing that person’s feelings, perceptions, and thoughts.”

Empathy should not be confused with sympathy, which is “a relationship or an affinity between people or things in which whatever affects one correspondingly affects the other,” or compassion which is “deep awareness of the suffering of another coupled with the wish to relieve it.”

The term “empathy” first appeared in psychological literature in 1910, when Titchner translated it into English from the German term, “Einfuhlung,” literally meaning “to feel oneself into”. Empathy later came to refer to a means for humans to understand each other as individuals with thoughts and feelings.

Empathy gained popularity as a psychological construct in the 1960s after the development of Rogers’ humanistic psychotherapeutic approach, in which empathy is a central component. However, for many years, most empathy-focused research was concentrated in the developmental and social areas of psychology, and was represented very little in the clinical and neurological psychology literature. In the past 20 years, the empirical investigation of empathy has gained momentum, and the construct of empathy has evolved.

What Are The Kinds of Empathy?

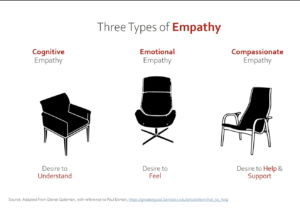

According to psychologist Daniel Goleman, there are three types of empathy. The first is cognitive empathy, which is intellectual awareness of the feelings, opinions and thoughts of others. Emotional empathy is the second, described as an ability to share the same emotional experience as another person. The third type is compassionate empathy, exemplified when we make efforts to help based on our understanding of the needs and feelings of others. The way we apply the three types of empathy also requires balance.

Daniel Siegel, a UCLA psychiatrist, calls the brain areas that create this resonance the “we” circuitry. Being in the bubble of a “we” with another person can signify chemistry, that sense of rapport that makes whatever we’re doing together go well – whether it’s in sales or a meeting, in the classroom,or between a couple. Dr. Siegel has even written about how to do this with your teenager.

We see the third variety, empathic concern, spring into action whenever someone expresses their caring about another person. This kind of empathy partakes of the brains’ circuitry for parental love – it’s a hear-to-heart connection. But it’s not out of place at work: you see it when a leader lets people know that he will support them, that he or she can be trusted, and that they are free to take risks rather than maintain a too-safe defensive posture.

Is Empathy Natural or Can it be Learned?

Both! Studies show that even newborn babies display empathy, or at least the early traces of it. For instance, newborns cry more when they hear other newborns cry, and it doesn’t seem to be because they’re merely upset by noise. A study by Abraham Sagi and Martin L. Hoffman found that newborns cried significantly more at the sound of another newborn crying but not at the synthetic sound of a newborn crying at the same intensity, suggesting a sort of inborn empathy.

From infancy, how a baby is raised greatly influences their capacity for empathy. A study authored by professor Ruth Feldman and colleagues found that babies who received more physical contact from their mothers grew up to have a better ability to empathize.

The findings from a meta-analysis of 18 empathy training trials, published in the Journal of Counseling of Psychology, suggest that empathy can be taught.

We can cultivate empathy throughout our lives, says Roman Krznaric—and use it as a radical force for social transformation says Roman Krznaric, Ph.D., a founding faculty member of The School of Life in London and empathy advisor to organizations including Oxfam and the United Nations, and he formerly taught sociology and politics at Cambridge University. He is the author of The Wonderbox: Curious Histories of How to Live and How to Find Fulfilling Work.

A new appreciation about empathy stems from a shift in the science of human nature. A predominant view that has been embraced for centuries and is popularly represented by such publications as Lord of the Flies, a 1954 novel by the Nobel Prize-winning British author William Golding. The plot concerns a group of British boys who are stranded on an uninhabited island and their disastrous attempts to govern themselves and their descent into barbarous behavior. Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies has sold tens of millions of copies, translated into more than 30 languages and hailed as one of the classics of the 20th century. In hindsight, the secret to the book’s success is clear. Golding had a masterful ability to portray the darkest depths of mankind.

The novel was named in the Modern Library 100 Best Novels, reaching number 41 on the editor’s list, and 25 on the reader’s list. The book has been criticized as “cynical” and portraying humanity exclusively as “selfish creatures”. It has been linked with Tragedy of the Commons by Garrett Hardin and books by Ayn Rand. And investigations into the real life events that inspired Golding’s book showed that his depictions were false, and the marooned boys were peaceful, organized and showed great emotional intelligence, including demonstrating empathy.

If there’s one belief that has been predominant for centuries is the tacit assumption that humans are bad. It’s a notion that drives newspaper headlines, TV shows and movies and guides the laws that shapes our lives. From the writings of Machiavelli to philosopher Thomas Hobbes and psychiatrist Sigmund Freud, and some would say even the Bible and Christianity, the roots of this belief have sunk deep into Western thought. Human beings, we have been taught, are by nature selfish and governed primarily by self-interest.

It’s difficult to disagree with this view when we experience the daily tragedies in war and domestic violence and inequality and poverty.

One of the best books to do this is Rutger Bregman’s HumanKind: A Hopeful History. Bregman provides new perspective on the past 200,000 years of human history, setting out to prove that we are hardwired for kindness, and empathy, and geared toward cooperation rather than competition, and more inclined to trust rather than distrust one another. In fact this instinct has a firm evolutionary basis going back to the beginning of Homo sapiens.

For example, A team of developmental psychologists led by Julia Ulber has published evidence in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology that paints a more heart-warming picture. These psychologists point out that most past research has focused on how much toddlers share things that are already theirs. The new study looks instead at how much they share new things that previously no one owned. In such scenarios, toddlers frequently show admirable generosity and fairness.

In another study published in Psychological Science, 112 three-year-old children, an equal number of boys and girls, were split into teams of two and observed sharing rewards and resources. In roughly 80 percent of these cases of cooperation, the sharing was “passive,” meaning that one child took what was fair — two prizes — and left the other two for his or her teammate. Other times, one child would take two prizes and actively give two to the other child, or would tell that child to collect his or her fair share if he or she neglected to do so at first. Rarely was there any arguing, and physical conflicts were almost nonexistent.

All of these altruistic behaviors would not have been possible without the presence of empathy.

“The big buzz about empathy stems from a revolutionary shift in the science of how we understand human nature. The old view that we are essentially self-interested creatures is being nudged firmly to one side by evidence that we are also homo empathicus, wired for empathy, social cooperation, and mutual aid” says Krznaric.

Over the last decade, neuroscientists have identified an“empathy circuit” in our brains which, if damaged, can curtail our ability to understand what other people are feeling. Evolutionary biologists like Frans de Waal argued in an article in the University of California (Berkeley)’s Greater Good Magazine that reminds us we are social animals that have evolved and succeeded as a species to care for each other.

And research psychologist A. Senju and colleagues have published a study in Psychological Science that argues we are primed for empathy at an early age of 18 months and researchers Mario Mikulincer and Philip Shaver have shown in their study published in Current Directions in Psychological Science the link between strong attachment and in the in the first two years of life.

Jamil Zaki, in his book The War for Kindness, “Our collaborative flair stems from empathy: the capacity to share, understand, and care about what others feel. Individuals who feel empathy in abundance experience greater happiness and less stress and make friends more easily. These benefits ripple outwards—patients of empathic doctors are more satisfied with their care, spouses of empathic individuals are more satisfied in their marriages, children of empathic parents are better able to manage their emotions, and employees of empathic managers suffer less from stress-related illness. Empathy strengthens our social fabric, encouraging generosity toward strangers, tolerance for people who look or think differently than we do, and commitment to environmental sustainability.”

Why We Need An Empathy Revolution in Business

Increasingly, we hear stories of toxic workplaces and toxic leaders in which incivility, abusive behavior and bullying are commonplace, even among those businesses which are financially successful. Both inside organizations, and in the world in general, never has there been a greater need for empathy and compassion toward others.

Baron-Cohen is a professor of developmental psychopathology at Cambridge University and one of the world’s leading experts on the psychology of empathy. The Science of Evil reports on what he has learned about the link between empathy and cruelty over more than two decades of research.

Although everyone is capable of temporary lapses of empathy, such as when we walk past a homeless person on our way to work, we usually feel guilty or remorseful after treating someone unkindly.

But people who lack empathy more completely and feel no remorse after hurting another—what he calls “Zero-Negative”—have dysfunctional brain patterns, which explains why they are able to do harm and, in some cases, commit the most horrific crimes. (Interestingly, there are a couple of disorders—autism and Asperger’s Syndrome—that Baron Cohen refers to as “Zero-Positive,” where people lack empathy but aren’t necessarily cruel to others.)

Baron-Cohen backs up his theory with evidence from studies using fMRI technology. Scientists have been able to study the brains of psychopaths—the people most likely to commit sadistic crimes—using this technology and have found gross abnormalities in their neural activity. For example, when psychopaths are shown pictures of people suffering from pain, fMRI scans of their brains reveal decreased activity in regions integral to the empathy circuit.

In another study, teens with high levels of aggression showed activity in the reward centers of the brain when they watched films depicting the infliction of pain on someone. This suggests that for people with anti-social personality disorders, a lack of empathy may be coupled with feelings of pleasure when witnessing another’s pain.

“I See You”

“Sawubona” is a Zulu greeting which basically means “we see you”. We saw a version of that idea in the movie Avatar. It’s a way of recognizing that how they understand what they see around them is a reflection of their perception that is derived not only from their own experiences, but from the stories and ideas passed down to them through their family and community.

Similarly, leaders need to remember that how we feel colours our perception of what we see going on around us and consequently, it’s important to understand those feelings so that we can respond and manage them accordingly.

Why Empathy Has Been Undervalued and Underdeveloped in Business

Research has so far demonstrated that business students and business leaders seem to have lower degrees of empathy. Sarah Brown and her colleagues for instance, assert that there are multiple studies reporting that business students are more focused on self-interest than students in other fields. Brown found that empathetic and narcissistic personality traits were significant predictors in ethical decision making. They further noticed that, of all business areas, finance students were least empathetic and most narcissistic.

Brown paints a grim picture of business students: they cheat more (holding the record with a 50% higher rate of reported cheating than any other major); are less cooperative, more likely to conceal instructors’ mistakes, less willing to yield and more likely to defect in bargaining games. Brown asserts that the mentality of unethical and narcissistic behavior follows business students into their professional careers, leading to the immoral organizational patterns we have come to know so well in recent years. They feel that business schools are still focusing too much on academic and social skill sets that will help students succeed in a competitive world, and too little on inter-human or ‘‘softer’’ skills.

Roger Karnes, in an article in the Journal of Business Ethics confirms that ‘‘empathy and social skills are under trained and under developed by organizations’’, and explains the downward spiral effect that starts with leadership void of emotional intelligence, leading to less empathy and social skills overall in organizations, expressed through employer–employee abuse, and ending in growing employee discontentment and all its consequences.

Considering the challenges of the fast-paced contemporary organizational environment, Wendy Mill Chalmers draws the interesting conclusion that there should be a positive correlation between hard demands and soft skills. ‘‘The ‘faster’ the workplace the more essential it is to inspirational leadership with emotional intelligence and an empathy and understanding of the development needs of their staff’’.

Chalmers adds that modern leaders need to engage in ‘‘21st century enlightenment’’, thereby not just responding to modern values, but shaping them. She reviews the ideology of possessive individualism that has become synonymous with consumer capitalism and democracy, and draws the conclusion that modern capitalism has fed self-interest, greed and unethical behavior, and undervalued empathy.

Yet, while empathy seems to be on the rise as a recognized leadership prerequisite, other sources warn that this quality takes time to develop. A 2006 study from the UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience found that young people are less capable of empathy-based emotions than more mature ones. The study, which was conducted by University College London, and presented at a British Association for the Advancement of Science festival at the University of East Anglia, concluded that the medial prefrontal cortex, which is the part of the brain that is ‘‘associated with higher-level thinking, empathy, guilt and understanding other people’s motivations – is often under-used in the decision-making process of teenagers’’. The study further reveals that the maturity process brings about a shift in brain use from the back part to the front, which is where the ‘‘soft behaviors’’

Daniel Goleman says that leaders credit empathy with helping them engage in more collaborative behaviors. For example, he says, they were more able to minimize the interference of judgment and bias, thereby improving the quality of their interactions. This openness was also linked to an improved ability to understand the true intentions behind the communication efforts of others.

Goleman argues managers with excellent cognitive empathy, for instance, get better than expected performance from their direct reports. And executives who have this mental asset do well when assigned to a culture different than their own – they are able to pick up the norms and ground rules of another culture more quickly.

Emotional empathy has different benefits. With emotional empathy we feel what the other person does in an instantaneous body-to-body connection. This empathy depends on a different muscle of attention: tuning in to another person’s feelings requires we pick up their facial, vocal, and a stream of other nonverbal signs of how they feel instant-to-instant. But in order to develop this kind of empathy we have to able to tune in to our own body’s emotional signals, which automatically mirror the other person’s feelings.

Goleman suggests that empathy is vital for leaders because it is positively related to the innate motivation of followers. Furthermore, empathy is helpful when solving problems in the workplace because it enables leaders to make immediate connections with employees, facilitates a more accurate assessment of employee performance, and yields better outcomes. Goleman states that empathy is a must-have virtue for leaders because it can inspire, motivate, envision, and lead others to greater effectiveness.

The need for empathy is increasingly important in the workplace where shared vision and openness are critical factors for success. Thus, possessing empathy helps a leader identify with his/her employees, i.e., to experience their pain and understand what it is like to be in their positions. Consequently, empathy is a vital skill for successful leadership since leaders who have a high degree of empathy towards their employees are in a position to become more effective leaders.

If you think your business practices empathy effectively, think again: less than 50 percent of employees in a recent Businessolver survey reported feeling that their companies were empathetic.

Simon Sinek titled his 2014 book Leaders Eat Last: Why Some Teams Pull Together and Others Don’t—a follow-up to his powerhouse Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. In Leaders Eat Last, Sinek proposes a concept of leadership that has little to do with authority, management acumen or even being in charge. True leadership, Sinek says, is about empowering others to achieve things they didn’t think possible. Exceptional organizations, he says, “prioritize the well-being of their people and, in return, their people give everything they’ve got to protect and advance the well-being of one another and the organization.”

In John Baldoni’s “How To Lead With Empathy (and When Not To)”, believes that a total lack of empathy is not positive, he believes that “empathy is the ability to have a heart, but leadership is the attribute to act on that heart when it matters.” Jill Kransny, who wrote “The Awesome Power of Empathy,”contends the best leaders at work are the ones who take time to listen to their employees, see other’s perspectives, and understand where an employee may be coming from.

Shelly Levitt writes in “Why the Empathetic Leader Is the Best Leader,”that helping others, expressing kindness and empathy provides a sensation of feeling good. Furthermore, she states that by training to be more empathic and by acting more congenial, there is a building effect. “Daily practice of putting the well-being of others first has a compounding and reciprocal effect in relationships, in friendships, in the way we treat our clients and our colleagues.”.

Ernest J. Wilson III and his colleagues at the University of Southern California conducted a comprehensive study on empathy in organizations. He reports: “For three years my colleagues and I at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism crisscrossed the U.S. and travelled to other nations asking business leaders what attributes executives must have to succeed in today’s digital, global economy. They identified five as critical: adaptability, cultural competence (the capacity to think, act, and move across multiple borders), 360-degree thinking (holistic understanding, capable of recognizing patterns of problems and their solutions), intellectual curiosity, and, of course, empathy.” Wilson says these so-called “soft” attributes constitute a distinctive way of seeing the world. Taken together, they create a kind of “Third Space”that differs sharply from the other two perspectives that have long dominated business thinking: the engineering and traditional MBA perspectives. Wilson goes on to report “Later, when we reported the results of our research to other leaders, many said empathy was the most important of the five attributes we had uncovered (though intellectual curiosity and 360-degree thinking were also popular). And this enthusiasm for empathy among business leaders crosses borders. Not only entertainment executives in Los Angeles and IT leaders in Manhattan but also PR professionals in Shanghai and digital businessmen and investors meeting in the Jockey Club in Beijing acknowledged the overwhelming importance of empathy. So did start-up founders in Rome and advertising professionals in Paris.”

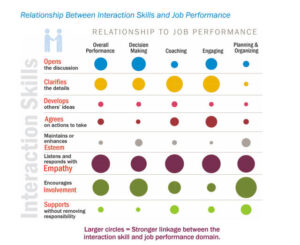

Global training giant Development Dimensions International (DDI) has studied leadership for 46 years. They believe that the essence of optimal leadership can be boiled down to having dozens of “fruitful conversations” with others, inside and outside your organization. Expanding on this belief, they assessed over 15,000 leaders from more than 300 organizations across 20 industries and 18 countries to determine which conversational skills have the highest impact on overall performance. The findings, published in their High Resolution Leadership report, are revealing.

The DDI report reveals a dire need for leaders with the skill of empathy. Only four out of 10 frontline leaders assessed in their massive study were proficient or strong on empathy.

Richard S. Wellins, senior vice president of DDI and one of the authors of the High-Resolution Leadership report, had this to say in a Forbes interview a year ago: “We feel empathy is in serious decline. More concerning, a study of college students by University of Michigan researchers showed a 34 percent to 48 percent decline in empathic skills over an eight-year period. These students are our future leaders! We feel there are two reasons that account for this decline. Organizations have heaped more and more on the plates of leaders, forcing them to limit face-to-face conversations.”

What Can We Do To Increase Our Capacity for Empathy?

Krznaric shows that research in sociology, psychology, history—”and my own studies of empathic personalities over the past 10 years—reveals how we can make empathy an attitude and a part of our daily lives, and thus improve the lives of everyone around us.”

He proposes several habits of highly empathetic people that could be emulated by everyone:

Cultivate curiosity about strangers. He says: “Highly empathic people (HEPs) have an insatiable curiosity about strangers. They will talk to the person sitting next to them on the bus, having retained that natural inquisitiveness we all had as children, but which society is so good at beating out of us. Curiosity expands our empathy when we talk to people outside our usual social circle, encountering lives and worldviews very different from our own . . . Cultivating curiosity requires more than having a brief chat about the weather. Crucially, it tries to understand the world inside the head of the other person. We are confronted by strangers every day, like the heavily tattooed woman who delivers your mail or the new employee who always eats his lunch alone. Set yourself the challenge of having a conversation with one stranger every week. All it requires is courage.”

Try another person’s life. Krznaric proposes: “So you think ice climbing and hang-gliding are extreme sports? Then you need to try experiential empathy, the most challenging—and potentially rewarding—of them all. HEPs expand their empathy by gaining direct experience of other people’s lives, putting into practice the Native American proverb, “Walk a mile in another man’s moccasins before you criticize him . . . George Orwell is an inspiring model. After several years as a colonial police officer in British Burma in the 1920s, Orwell returned to Britain determined to discover what life was like for those living on the social margins. ‘I wanted to submerge myself, to get right down among the oppressed,’ he wrote. So he dressed up as a tramp with shabby shoes and coat, and lived on the streets of East London with beggars and vagabonds. The result, recorded in his book Down and Out in Paris and London, was a radical change in his beliefs, priorities, and relationships. He not only realized that homeless people are not ‘drunken scoundrels’—Orwell developed new friendships, shifted his views on inequality, and gathered some superb literary material. It was the greatest travel experience of his life. He realised that empathy doesn’t just make you good—it’s good for you, too.”

Listen empathetically. There are two traits required for being an empathic conversationalist.One is to master the art of radical listening. “What is essential,” says Marshall Rosenberg, psychologist and founder of Non-Violent Communication (NVC), “is our ability to be present to what’s really going on within—to the unique feelings and needs a person is experiencing in that very moment.” Krznaric says “HEPs listen hard to others and do all they can to grasp their emotional state and needs, whether it is a friend who has just been diagnosed with cancer or a spouse who is upset at them for working late yet again . . . But listening is never enough. The second trait is to make ourselves vulnerable. Removing our masks and revealing our feelings to someone is vital for creating a strong empathic bond. Empathy is a two-way street that, at its best, is built upon mutual understanding—an exchange of our most important beliefs and experiences . . .We typically assume empathy happens at the level of individuals, but HEPs understand that empathy can also be a mass phenomenon that brings about fundamental social change . . . Empathy will most likely flower on a collective scale if its seeds are planted in our children. That’s why HEPs support efforts such as Canada’s pioneering Roots of Empathy, the world’s most effective empathy teaching program, which has benefited over half a million school kids. Its unique curriculum centers on an infant, whose development children observe over time in order to learn emotional intelligence—and its results include significant declines in playground bullying and higher levels of academic achievement.”

A good warm up is to do a quick assessment of your empathic abilities. Neuropsychologist Simon Baron-Cohen has devised a test called Reading the Mind in the Eyes in which you are shown 36 pairs of eyes and have to choose one of four words that best describes what each person is feeling or thinking – for instance, jealous, arrogant, panicked or hateful.

The average score of around 26 suggests that the majority of people are surprisingly good – though far from perfect – at visually reading others’ emotions.

Other Strategies for Improving Your Empathetic Skills

Ask questions. Rather than taking a close-minded approach and assuming you know what someone means, empathy calls you to remain open and try to clarify to ensure you’ve understood. Asking questions is crucial to understanding someone else’s perspective. Practicing this is a key part of learning how to be more present and empathetic. And be silent. A response is not always needed. Sometimes silence can encourage the other person to expand on their thoughts and feeling

Mirror the other person’s body language. Words matter, but they’re not the only way we communicate. A rich depth ofcommunication lies in our body language, facial expressions and voice. For instance, if your friend shows up to lunch and says, “John and I just broke up,” your initial instinct might be to frown and say sorry because a breakup seems like bad news. But let’s say that when your friend delivers this news, her tone of voice is cheerful; she’s sitting tall and smiling. Using your emotional intelligence, you can read her body language and tone of voice and tell this must be good news for her. You might, in turn, smile and say, “Wow, this sounds like big news. Tell me more!” This mirroring of body language and tone signals to your friend that you were practicing empathetic listening.

Share a personal experience. Sharing a time when you went through something similar can show the other person that you were listening to what they said and understand their pain in a particular way. It can help them feel less alone in their situation. Proceed with caution on this one, though. Don’t try to “one-up” them about the time you, too, got into an argument with a good friend or got rejected for an opportunity they really wanted. In a paper published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, researchers from the University of Amsterdam found that having had a similar negative experience as someone else increases feelings of closeness and empathy, but it blinded the listener to what the other person was truly feeling. The authors write: “Whereas ‘I know how you feel, I’ve been there too’ is a common way to express understanding of another’s feelings, it may actually not be helpful to ‘have been there too’ in order to better understand how someone else feels.”

Read fiction.Empathy involves putting yourself in another’s shoes, and what better way to do that than reading a novel or short story? Fiction forces you to use your imagination to think, feel and act the way a character does—not unlike what you have to do in real life when empathizing with someone! In fact, research suggests engaging in narratives and storytelling can boost our empathy. Keith Oatley, a novelist and professor at the University of Toronto, conducted a review of multiple studies that seem to support that. “Both fiction and everyday consciousness are based on simulations of the social world,” he writes in his review, which was published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. “Thus, reading a work of fiction can be thought of as taking in a piece of consciousness.” In one study included in Oatley’s review, participants read an excerpt from Saffron Dreams, a book by Shaila Abdullah. In it, the protagonist, a Muslim woman, experiences racial slurs and insults from a group of teenagers. Participants who read the excerpt showed decreased racial bias in post-testing compared to the group that did not read the excerpt.

Get to know people from other cultures.I t’s probably no surprise that meeting people from different cultures and backgrounds can improve your ability to see things from another perspective. But now, we have research to support that. Researchers from the University of Zurich conducted an experiment between people who were members of two different ethnic groups. They found that when an “in-group” member had positive experiences with an “out-group” member, their empathy, as measured via brain activation, increased for the out-group members. The researchers concluded that even a handful of positive experiences with people that you consider to be a member of an out-group is enough to increase your empathy for not only them but other members of their group as well. You don’t even have to travel outside of your city to meet people from different cultures and backgrounds. Try attending an international travel meetup. Those typically have lots of people from all over the world, allowing you to “travel” without leaving your town. Ask them open-ended questions, and listen to what they have to say. Some experts argue that Americans lack of tolerance and feelings of prejudice about other cultures and ethnicity is reflected in their unwillingness to travel outside their homes. Research of 2,000 Americans across the country (a good statistical sample) in a study conducted by market researchers OnePoll, and commissioned by travel luggage provider Victorinox, explored the nation’s travel experiences and the things that seem to stop people from exploring more. The results are pretty amazing, and perhaps explain the gaps of knowledge many Americans seem to have of the world: Eleven percent of survey respondents have never traveled outside of the state where they were born; over half of those surveyed (54 percent) say they’ve visited 10 states or fewer; as many as 13 percent say they have never flown in an airplane; forty percent of those questioned said they’ve never left the country; over half of respondents have never owned a passport.

Get better at identifying the nuances in emotions. Boosting your emotional intelligence, which involves properly identifying emotions in yourself and others, can help you empathize better. How? To even begin to understand, you must first label what you’re seeing. Is your friend frustrated or disappointed? Are they excited or stressed? Sometimes, it’s a fine line between two different emotions, and how you should respond to one emotion may be different from how you should respond to another.One helpful way to get better at identifying emotions is to use an emotion wheel or something similar that helps you see the vast array of feelings or the do Mood Meter app, and it can help to identify and log varying emotions throughout the day. By being able to identify and describe emotions, not only do you get better at understanding what I’m feeling, but you also get better at finding out how others are feeling (a crucial part of empathy).

Take an empathetic quiz. The University of California (Berkeley)’ Greater Good Science Center has a free online empathy quiz that can quickly assess how empathetic you are.

Final Thoughts:

Today’s world is fraught with natural and man-made disasters. We have a choice that could be reinforcing our belief about the dark side of humanity and engage in behaviors to validate that belief or we can choose to believe in the innate goodness of human beings and engage in empathetic and compassionate behaviors to validate that belief. The urgency for action is upon us.