You’re about to take and exam or give a speech and your mind goes blank. Or we’ve got an important shot to make in tennis or golf, and you blow it.

You’re not alone.

For most of us, at one time or another, we’ve struggled with decisions or performance under pressure. We can cope or choke.

Psychologists have studied the issue of coping under pressure extensively both the chronic version and the single crucial event.

The Stress Mindset

Your “stress mindset” is a term that is becoming more widely acknowledged as being important with regard to coping with pressure. You have a “positive” stress mindset if you understand how stressful situations can help you focus more intently, boost your motivation, and present opportunities for learning and success. In contrast, viewing stress as unpleasant, debilitating and negative constitutes a “negative” stress mindset. According to a 2017 study led by Anne Casper published in the European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology found that when faced with a day that they know is going to be challenging, people with a positive stress mindset come up with coping strategies, boost their performance, and end the day feeling more energized. For people with a negative stress mindset, the opposite happens.

Daeun Park and colleagues published a study in Child Development, that found it’s not just adults who benefit. In a study of adolescents, the researchers found that those who believed in the potential benefits of stress were less prone to feeling stressed in the wake of difficult life events. “These findings suggest that changing the way adolescents think about stress may help protect them from acting impulsively when confronted with adversity,” the researchers concluded.

There are strategies to change your perspective if you do have a negative mindset about stress. In another study published by in Anxiety, Stress & Coping, Crum’s team found that adult participants who’d watched a film clip that focused on the “enhancing” nature of stress, and were then put into a stressful social situation, afterwards felt more positive and showed greater cognitive flexibility than participants who’d first watched a “stress is bad” clip.

Sonia Kang and colleagues published a study in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin which described how the researchers put some into positions of low power in a negotiating situation, and found that these participants performed worse under pressure than those who’d been given more power over the outcome. However, when “low power” students first spent five minutes writing about their most important negotiating skill, this neutralised the power differential effect on performance. “Anytime you have low expectations for performance, you tend to sink down and meet those low expectations,” Kang observed. “Self-affirmation is a way to neutralize that threat.”

Choking Under Pressure

We’ve all heard of or experienced ourselves the mental or physical “brain freeze” that’s often described as “choking” under pressure.

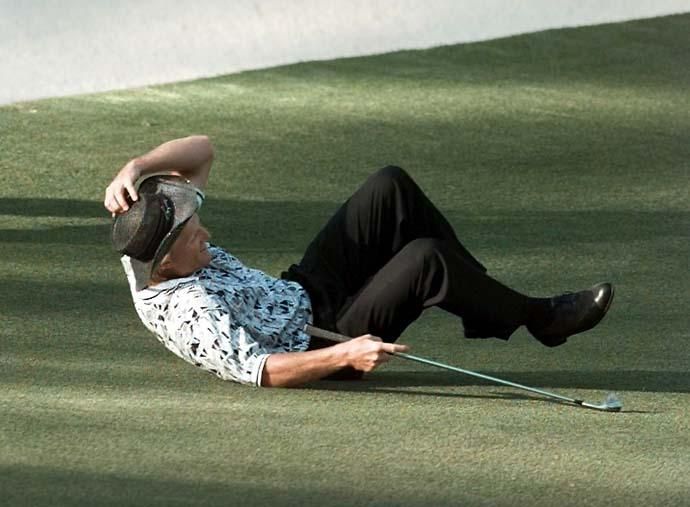

Why did Michelle Kwan, favoured to win the gold medal in the 2002 Olympics, fall on a triple jump, leaving the gold to Sarah Hughes? Why did Greg Norman lose his lead and the Masters to Nick Faldo in 1996? Why do actors, singers, musicians and public speakers freeze or “choke” when asked to perform, even if they are experienced? While this is frequently described as a result of anxiety or nervousness, new research points to a type of “log-jam” in the brain.

When the pressure gets “too much”, our skills suddenly deteriorate, and we perform more poorly than we, or anyone else, expected. Unsurprisingly, this phenomenon has been extensively studied in sport. One analysis of the performance of elite tennis players, led by Danny Cohen-Zada, concluded that the male players were about twice as adversely affected by high pressure as the female players, perhaps because men typically show a bigger spike in levels of the stress hormone cortisol when under pressure than women do. (“Our robust evidence that women can respond better than men to competitive pressure is compelling,” the researchers noted.)

A group led by Christian Swann at the University of Wollongong, Australia interviewed 16 top athletes and asked them to describe what they were thinking and feeling during a recent outstanding “clutch” performance. This led them to identify 12 characteristics associated with excelling under pressure. Six were similar to the state of flow (they became so involved in their task they became unaware of the crowd, for example). But six were different. They included being deliberately focused on the task in hand, maintaining intense effort over a period of time, feeling high arousal levels, and not thinking about what would happen if they failed. The athletes talked about making a big effort to monitor their own performance as they played, to raise their game. (It’s worth noting that though the athletes talked about feeling high levels of arousal, their actual physiological arousal was not monitored. There’s certainly work finding that arousal helps with performance — only to a point.)

University of Chicago psychologist Sian Beilock’s research on this issue, published in her book, Choke: What the Secrets of the Brain Reveal About Getting It Right When You Have To, describes how a star athlete can collapse in a competition or student fail a critical test, or a professional botch a presentation.

“Choking is suboptimal performance, not just poor performance. It’s a performance that is inferior to what you can do and have done in the past and occurs when you feel pressure to get everything right,” argues Beilock.

In an article in Scientific American, Dr. Ellen Hendriksen says “it’s not just objectively pressure-filled situations, it’s anytime you psych yourself out

For instance, a recent study found that people who are lonely tend to choke under self-imposed social pressure. When we feel desperate to connect, we end up spilling our drink or tripping over our feet, and not in an adorable Jennifer Lawrence kind of way.

A study which examined the film footage of 400 penalty kicks in professional soccer games noticed that players who took less than a second to place the ball down scored only 58% of the time while those players who did not rush and took longer than a second scored 80% of the time.

Smarter people also choke more. Specifically, Beilock has found that people who have greater working memory (the amount of stuff you can actively hold in your mind at once) are more prone to choking when doing math problems in a high-pressure situation.

One reason for that? These people are used to being able to get by with their big working memories to solve these problems. But when their working memory gets clogged with worry, they have to switch to using other kinds of strategies that they’re not as accustomed to. This ends up taking away some of their natural advantages.

Despite the fact that not choking involves not thinking, clearing your mind often, paradoxically, involves a deliberate routine. Pitchers may check the bases, regardless if any players are on them, before a pitch. Basketball players may dribble a certain way, or throw the ball up in the air, before taking a free throw. When you rush into any of these scenarios, you hamper your body’s ability to go into auto-pilot, and thus increase your chances of choking.

It turns out that being too attached to winning may have been what caused Maroney to choke, according to some new research from neuroscientists Johns Hopkins University.

Whether you choke under pressure might have more to do with your motivation: specifically, to what extent that you are driven by a desire to win or by a desire to avoid losing. If you’re very loss-averse — meaning that you hate losing more than you love winning — your chances of choking will be lower. But for those who value the rush of winning over the pain of losing, the likelihood of choking is often higher.

The Johns Hopkins study found that those who hated losing the most choked when told that they stood to win the most, while those who cared more about winning choked when they stood to lose something significant. In other words, it’s all about how you frame the incentive: as a loss or as a gain.

“We can measure someone’s loss aversion and then frame the task in a way that might help them avoid choking under pressure,” Vikram Chib, Ph.D., assistant professor of biomedical engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, said in a statement.

The researchers explain this phenomenon by looking at the ventral striatum, a brain region that may connect incentive-driven motivation and the execution of physical performance. The activity of this brain region suggests that an individual’s attachment to winning is key to how they perform under pressure.

“We found that the way we framed an incentive — as a potential gain or loss — had a profound effect on participants’ behavior as they performed the skilled task,” Chib said in the statement. “But the effect was different for those with high versus low aversion to loss.”

High loss aversion actually helped participants when they faced increasing losses — they didn’t choke, even when the loss was significant. The opposite happened to those with low loss aversion: their performance improved with both increasing prospective gains and increasing prospective losses, but they choked when threatened a significant loss.

While all of this was happening, MRI images were being taken of the participants’ brains, focusing on the ventral striatum, that small area of the brain associated with reward processing and movement control. They saw that when both loss and gain incentives were presented, ventral striatum activity increased with the magnitude of the stakes.

More loss-averse participants had lower striatal activity (and thus performed worse) when playing for large potential wins, whereas more winning-attached participants had less striatal activity (and worse performance) when attempting to avoid losing.

“We have known from previous studies that the ventral striatum is responsible for representing information about incentives and motor performance, but this study shows how it mediates the relationship between incentives and performance,” Chib explained in an email to the Huffington Post. “We show that in the situations when people choke under pressure there is a break down in the connectivity between ventral striatum and the motor cortex (the are responsible for coordinating our movements). These breakdown in communication between these areas could be causing individuals to choke under pressure.”

So how can we apply this information to improve our own performance? One way would be to use cognitive strategies to reframe high-stakes situations so as to help minimize your chances of poor performance. So if you’re someone who plays to win, try to avoid framing the situation more in terms of what you could stand to lose. “From this study, it seems that knowing an individual’s loss aversion could be used to determine the best way to frame incentives in the workplace,” Chib added.

What to Do About Choking

By studying how the brain works when we are doing our best – and when we choke – Beilock has formulated practical ideas about how to overcome performance lapses at critical moments.

Thinking too much about what you are doing, because you are worried about losing a competition or worrying about failing in general, can lead to over-analyzing the situation. This paralysis by analysis occurs when people try to control every aspect of what they are doing in an attempt to guarantee success. However, this increased attempt at control can backfire, disrupting what was once a fluid or flawless performance.

“My research team and I have found that highly skilled golfers are more likely to hole a simple 3-foot putt when we give them the tools to stop analyzing their shot, to stop thinking,” Beilock said. “Highly practiced putts run better when you don’t try to control every aspect of performance.” Even a simple trick of singing helps prevent portions of the brain that might interfere with performance from taking over, Beilock’s research shows.

The brain also can work to sabotage performance in ways. Pressure-filled situations can deplete a part of the brain’s processing power known as working memory, which is critical to many everyday activities. Beilock contends as a result of her research that working memory helps people perform at their best in physical, intellectual and applied situations including business. This working memory is located in the prefrontal cortex that serves as a limited temporary storage for information needed to complete immediate tasks. Very talented and able people have larger working memories, but this is where the problem arises. When anxiety or fear creeps in, the working memory becomes overtaxed, and you loose the brain power to succeed.

Choking can also result from what is termed “stereotype threat,” when otherwise talented people don’t perform up to their abilities because they are worried about confirming popular cultural myths. Examples are that boys and girls naturally perform differently in math or that a person’s race determines his or her test performance. Another example is when a racial group or gender to which they belong is widely believed to be either inferior at tasks. These worries deplete the working memory necessary for success. The perceptions take hold early in schooling and can be either reinforced or abolished by powerful role models.

In one study, researchers gave standardized tests to black and white students, both before and after President Obama was elected. Black test takers performed worse than white test takers before the election. Immediately after Obama’s election, however, blacks’ performance improved so much that their scores were nearly equal with whites. When black students can overcome the worries brought on by stereotypes, because they see someone like President Obama who directly counters myths about racial variation in intelligence, their performance improves.

Beilock and her colleagues also have shown that when first-grade girls believe that boys are better than girls at math, they perform more poorly on math tests. One big source of this belief? The girls’ female teachers. It turns out that elementary school teachers are often highly anxious about their own math abilities, and this anxiety is modeled from teacher to student. When the teachers serve as positive role models in math, their male and female students perform equally well.

Even when a student is not a member of a stereotyped group, tests can be challenging for the brightest people, who can clutch if anxiety taps out their mental resources. In these circumstances instance, meditation, which has been widely researched for its benefits, can help significantly.

In tests in her lab, Beilock and her research team gave people with no meditation experience 10 minutes of meditation training before they took a high-stakes test. Students with meditation preparation scored 87, or B+, versus the 82 or B- score of those without meditation training. This difference in performance occurred despite the fact that all students were of equal ability.

Stress can lead to choking and undermine performance in the world of business, where competition for sales, giving high-stakes presentations or even meeting your boss in the elevator are occasions when choking can squander opportunities.

Paying too much attention to well-learned skill execution may be detrimental to performance. Understanding the cognitive mechanisms leading to poor performance under pressure, as shown in these experiments, can lead to prevention, says Beilock, in “real-world tasks in which serious consequences depend on good or poor performance in relatively public or consequential circumstances.”

For example, many aspects of public speaking may ordinarily be automatic. However, lawyers giving a closing argument to a jury may feel pressure to perform, and as a result, think too much about what they are doing –and stutter or lose their train of thought. Training under conditions that have individuals attend to their performance, or, conversely, purposely taking one’s mind off well-learned skill performance under pressure. For example, repeating a key word, singing a song, seeing a favorite image, recalling a pleasurable event, can help prevent choking.

We know from research on mastering skills or tasks, that practice, and a lot of it is necessary. But, practicing under stress – even a moderate amount – helps a person feel comfortable when they find themselves standing in the line of fire, Beilock said. The experience of having dealt with stress makes those situations seem familiar, and not so daunting. The goal is to close the gap between practice and performance.

“Think about the journey, not the outcome,” Beilock advised. “Remind yourself that you have the background to succeed and that you are in control of the situation. This can be the confidence boost you need to ace your pitch or to succeed in other ways when facing life’s challenges.”

Henriksen recommends “Play like you don’t care. I often tell athletes to separate the process from the outcome. The more we fixate on the outcome, whether or not a play was executed properly, whether or not the other team is ahead or not, the more likely we are to choke up. Athletes need to both play as if they don’t care about the outcome while simultaneously giving the game their all.”

Here’s some other strategies from researchers that help deal with the choking issue:

- Channel your inner Stuart Smalley. Stuart Smalley was a fictional character created by Al Franken on Saturday Night Live. Stuart was famous for his daily affirmations, most notably, “I’m good enough, I’m smart enough, and doggone it, people like me.” As it turns out, taking a few minutes to write about your strengths and interests can promote feelings of self-worth, which boosts both confidence and performance. Similarly, identifying all of the things that go into make you who you are can give you some perspective – you are more than just one test score.

- Do a brain spill. Dr. Beilock suggests writing for 10 minutes about what your biggest worries are with your upcoming presentation or performance. When your worries are on the table your brain can switch gears, which reduces the cognitive pressure and may lead to improved working memory.

- Get control of your breathing. Did you know that we typically use only 10-30% of our lung capacity? Stress and the other strong emotions you might experience leading up to your performance deplete that capacity even further.

- Choke your choke. If you are stuck trying to solve a challenging problem or focused on any task that requires working memory, walk away for a few minutes. This pause is called the incubation period and helps your brain switch channels and find an alternative perspective.

- Think of the stress as a challenge. When you have a physiological response to stress, try to interpret that response as a challenge and not a threat. For example, if your heart is racing, think of it as a sign that your body is getting ready to help you do well and focus versus thinking of it as a sign that you’re going crazy and aren’t prepared.

- Practice under pressure. While you likely can’t replicate the exact stress or pressure you might feel on the day of your performance, even practicing under mild levels of stress can prevent you from choking. If you’re preparing for a big presentation and won’t be able to use your notes, time yourself in advance and make sure you do a few practice runs without your notes.

- Distract yourself a bit. For physical tasks, such as sports competitions, many people end up thinking too hard about what they’re doing, which can throw them off. Beilock has shown that experienced golfers actually do worse when encouraged to focus on the skill at hand. So she has suggested self-distraction — like, for example, focusing on a golf ball’s dimples or singing a song.

- Don’t dilly-dally. Beilock has demonstrated that doing a task relatively quickly seems to help. For example, in one study she found that experienced golfers putted better when instructed to putt quickly while still being accurate. (Though the opposite was true with novices.) So if you’re doing something you know how to do really well, taking extra time could make you more susceptible to choking.

- Express your emotions before you start. Beilock’s research group has also shown that writing about one’s feelings before a test can help. In a study published in Science in 2011, they explored this by having college students take a very difficult math exam. (Sara Reardon has a good summary for Science.) To boost the pressure, the researchers put some cash on the line and videotaped the subjects, telling them the tape would be shown to their teachers and friends.

- Abandon perfectionism. You can’t be perfect every time in everything you do. Think both about percentages and doing the best you can. Percentages means doing the task a whole bunch of times, and some of the results will be great, and some not. But if you only do the task a few times, the failures loom much larger in your mind. As hockey legend Wayne Gretsky once said “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.” Doing the best you can at the time is a better way of measuring your performance rather than expecting 100% or perfection every time, because it takes the psychological pressure off, which in turn helps your performance.