By Ray Williams

July 20, 2020

Introduction

Capitalism is facing at least three major crises. A pandemic-induced health crisis has rapidly ignited an economic crisis with yet unknown consequences for financial stability, and all of this is playing out against the backdrop of a climate crisis that cannot be addressed by “business as usual.”

This triple crisis has revealed several problems with how we do capitalism, all of which must be solved at the same time that we address the immediate health emergency. Otherwise, we will simply be solving problems in one place while creating new ones elsewhere. That is what happened with the 2008 financial crisis. Policymakers flooded the world with liquidity without directing it toward good investment opportunities. As a result, the money ended up back in a financial sector that does little to help the economic well-being of the general population.

We have now reached a point in the twenty-first century in which the externalities of the capitalist system, such as the costs of war, the depletion of natural resources, the waste of human lives, the inability to marshal resources efficient to meet the pandemic and the disruption of the planetary environment, now far exceed any future economic benefits that capitalism offers to society as a whole. The accumulation of capital and the amassing of wealth are increasingly occurring at the expense of an irrevocable rift in the social and environmental conditions governing human life on earth.

Less than two decades into the twenty-first century, it is evident that capitalism has failed as a social system. The world is mired in economic stagnation, financialization, and the most extreme inequality in human history, accompanied by mass unemployment and underemployment, precariousness, poverty, hunger, wasted output and lives, and what at this point can only be called a planetary ecological “death spiral.”

Shifting Public Attitudes Re: Capitalism

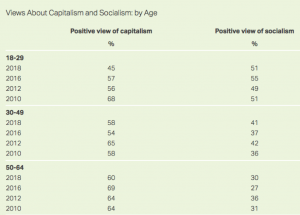

According to an April 2016 Harvard University poll, support for capitalism is at a historic low 51 percent of Americans in this age cohort reject it, while 42 percent support it. 33 percent say they support socialism. The Harvard poll echoes a 2012 Pew survey, in which 46 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds had a positive view of capitalism, and 47 percent a negative one. While older generations had a slightly more positive take on capitalism — topping out at 52 percent for the oldest cohort, citizens over 65 — youth had a markedly different take on socialism. 49 percent viewed it positively, compared to just 13 percent of those 65 or older. A YouGov poll in 2015 found that 64% of Britons believe that capitalism is unfair, that it makes inequality worse. Even in the U.S., it’s as high as 55%. In Germany, a solid 77% are skeptical of capitalism. Meanwhile, a full three-quarters of people in major capitalist economies believe that big businesses are basically corrupt.

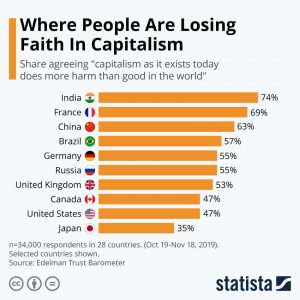

For the past two decades, “The Edelman Trust Barometer” has polled thousands of people about their trust levels in core institutions and the latest edition of the survey found that there is a distinct feeling of pessimism around the world today. In 15 of the 28 markets surveyed, a majority of people said they are pessimistic about their economic prospects over the coming five years. 56% of respondents surveyed by Edelman for its annual Trust Barometer agreed that capitalism “is doing more harm than good in its current form.” In more than half the markets surveyed, a majority of people said they are pessimistic about their economic prospects over the coming five years. Despite a strong economy and near full employment, none of the core societal institutions in the survey – government, business, NGOs and the media – were trusted. Notably, the study also found that a majority of respondents are losing faith in the capitalist system.

Some countries have more faith in the system, especially in North America where less, 47 percent in both the U.S. and Canada, agree with the statement. In Japan, critical feelings about capitalism are even lower at 35 percent. Edelman found that global cynicism about capitalism and concerns regarding the fairness of our current economic system are resulting in deep-rooted fears about the future. 83 percent of people in the markets surveyed are afraid they will lose their job, attributing that fear to several factors such as automation, the fragility of working in the gig economy and the risk of a recession.

Just 56% of Americans say they have a positive image of capitalism,according to a Gallup poll last summer, compared with 37% who said the same thing about socialism. In a Fox News poll during the same period, 36% of adults approved of a shift in the U.S. “away from capitalism and more toward socialism”—a huge increase from 2012, when just 20% said so.

Among Millennials and Gen Z, free market skepticism is actually the majority view. In Gallup’s poll, 51% of those 18 to 29 had a positive view of socialism—albeit the largely fuzzy Scandinavian/Bernie Sanders version rather than the Soviet/Berlin Wall hard stuff—compared with 45% for capitalism. That finding was echoed by a Harvard survey of young adults in which 51% said they did not support capitalism and only 19% said they “identify as a capitalist.” These sentiments come amid an economy that by all traditional measures is booming, with full employment and 3% growth.

Unsurprisingly, millennials—many of whom came of age in the midst of the worst financial meltdown since the Great Depression—have a particularly unfavorable view of capitalism, regardless of party affiliation.

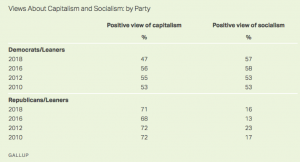

According to Gallup, just 45 percent of millennials view capitalism favorably, down from 68 percent in 2010. By contrast, 51 percent of millennials view socialism favorably. “The system has failed tens of millions of people who want and deserve something better,” Kenneth Zinn, political director of National Nurses United, wrote in response to the new data. “A change is gonna come.”

Equally significant has been a shift in emotional intensity. Climate change used to be something most everyone said they cared about—just not all that much. When Americans were asked to rank their political concerns in order of priority, climate change would reliably come in last.

But now there is a significant cohort of Republicans who care passionately, even obsessively, about climate change—though what they care about is exposing it as a “hoax” being perpetrated by liberals to force them to change their light bulbs, live in Soviet-style tenements and surrender their SUVs. For these right-wingers, opposition to climate change has become as central to their worldview as low taxes, gun ownership and opposition to abortion.

What is Capitalism?

Capitalism can be defined as an “economic and political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state.”

Capitalism requires a free market economy to succeed. It distributes goods and services according to the laws of supply and demand. The law of demand says that when demand increases for a particular product, price rises. When competitors realize they can make a higher profit, they increase production. The greater supply reduces prices to a level where only the best competitors remain.Capitalism ignores external costs, such as pollution and climate change. This makes goods cheaper and more accessible in the short run. But over time, it depletes natural resources, lowers the quality of life in the affected areas, and increases costs for everyone.

Economists, political economists, sociologistsand historians have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include laissez-faire or free market capitalism, welfare capitalism and state capitalism. Different forms of capitalism feature varying degrees of free markets, public ownership,obstacles to free competition and state-sanctioned social policies. The degree of competition in markets, the role of intervention and regulation, and the scope of state ownership vary across different models of capitalism.

The extent to which different markets are free as well as the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most existing capitalist economies are mixed economies, which combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases economic planning.Critics of capitalism associate the economic system with social inequality; unfair distribution of wealth nd power; materialism; repression of workers and trade unionists; social alienation; economic inequality; unemployment; and economic instability.

Many socialists consider capitalism to be irrational in that production and the direction of the economy are unplanned, creating many inconsistencies and internal contradictions.Capitalism and individual property rights have been associated with the tragedy of the anticommonswhere owners are unable to agree. Marxian economist Richard D. Wolffpostulates that capitalist economies prioritize profits and capital accumulation over the social needs of communities and capitalist enterprises rarely include the workers in the basic decisions of the enterprise.

Democratic socialists argue that the role of the state in a capitalist society is to defend the interests of the bourgeoisie.These states take actions to implement such things as unified national markets, national currencies and customs system. Capitalism and capitalist governments have also been criticized as oligarchic in nature due to the inevitable inequality characteristic of economic progress.

Capitalistic ownership means two things. First, the owners control the factors of production. Second, they derive their income from their ownership. That gives them the ability to operate their companies efficiently. It also provides them with the incentive to maximize profit. This incentive is why many capitalists say “Greed is good.”

The Problems With Capitalism Today

The global financial crisis, which began in 2008 and whose repercussions will continue to echo round the world for years to come, has triggered myriad criticisms of the modern capitalist system: it is too ‘speculative’; it rewards ‘rent-seekers’ over true ‘wealth creators’; and it has permitted the rampant growth of finance, allowing speculative exchanges of financial assets to be compensated more than investments that lead to new physical assets and job creation; and it rewards the rich while not passing economic gains onto the middle and poorer classes.

Debates about unsustainable growth have become louder, with concerns not only about the rate of growth but also its direction. Recipes for serious reforms of this ‘dysfunctional’ system include making the financial sector more focused on long-run investments; changing the governance structures of corporations so they are less focussed on their share prices and quarterly returns; taxing quick speculative trades more heavily; legally and curbing the excesses of executive pay.

Meanwhile, as Harvard Business Review points out, contemporary society is characterized by a sense of alienation among workers distanced from the output of their labor, and the fetishization of commodities—both predicted by Karl Marx. Inequality experts Jason Hickel and Martin Kirk launched a conversation in which they posed the theory that capitalism is at the core of the many crises gripping our world today.

In 2011, the same year that Occupy Wall Street injected dissatisfaction with the financial system into the American mainstream, Richard Wolff founded Democracy at Work, a nonprofit that advocates for worker cooperatives–a business structure in which the employees own the company, and share decision-making power over salaries, schedules, and where profits are directed. “If I had to pinpoint right now where the transition away from capitalism is happening in the United States, it’s in worker co-ops,” Wolff says.

These developments are all happening outside of the political system; in the White House and in Congress, the presence of big capitalist businesses continues as strong as ever. But the fact that local governments like New York City and Austin have launched incubator programs for worker-owned cooperatives indicates that they’re not incompatible with the current political system.

Why is predatory, consumeristic capitalism on its way out? A number of factors are simultaneously converging:

- The human population growth is tapering off. Many people alive today will be alive to witness the most significant moment in our collective history — the human population peak. Capitalism is based on perpetual growth, which is not compatible with permanent population decline. Some of the challenges related to population decline will include abandoned cities, “rewilding,” and permanent economic shrinkage.

- We are running into severe environmental limitations. We have triggered the Anthropocene, a geological age characterized by mass extinctions, radical changes in local climates, overall global warming, acidification of oceans from excess CO2 absorption (which will result in almost no fish or coral reefs, but lots of jellyfish and algae), rising sea levels (and massive floods), endless droughts (resulting in the current “Dustbowlification”of the central US, deforestation, chemical pollution, gargantuan gyres of plastic detritus. These problems are a direct result of a devouring capitalist system that sidelines such considerations as “externalities.”

- We are in the midst of a radical reorganization of production methods. More and more things are essentially free to produce and distribute, and can be shared/co-created via networks and decentralized production centers (home workshops, personal computers, 3D printers). Open-source production methods, freeware, and peer-to-peer distribution methods directly threaten top-down, strictly controlled capitalistic profit-generation models. Open-source is upending capitalism.

- Attitudes toward capitalism are changing. The United States, the world’s glowing beacon of capitalistic success, is no longer so shiny. Vast regions of the country display decrepit infrastructure. Cities are going bankrupt. Real unemployment is high and underemployment is rampant. Millions go without access to professional healthcare. Its educational system produces only middling results. Wealth inequality is extremely high. Meanwhile, nations that lean more towards social democracy sport better infrastructure, better educated kids, nicer looking cities, cleaner environments, and healthier, happier citizens.

The 10,000-year pyramid scheme that has been generating wealth at the expense of non-renewable planetary resources has reached its limit. We have exhausted, in order, mega-fauna, pristine virgin forests, fossil fuels, free food from the ocean, fresh water sources, and an atmosphere that regulates temperature, rainfall, and local weather patterns. We have even used up some elements (like helium, which permanently escapes into outer space), and destroyed entire landscapes to extract gold, silver, copper, and rare metals.

Former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis has claimed capitalism is coming to an end because it is making itself obsolete. The former economics professor told an audience at University College London that the rise of giant technology corporations and artificial intelligence will cause the current economic system to undermine itself. “So now there is no doubt capital is being socially produced, and the returns are being privatized. This with artificial intelligence is going to be the end of capitalism.”

Critics of Capitalism

The critics of capitalism are increasing, as itbecomes apparent the damage that unrestrained capitalism has unleased on the world.

Critics argue that capitalism leads to a significant loss of political, democratic and economic power for the vast majority of the global human population. The reason for this is they believe capitalism creates very large concentrations of money and property in the hands of a relatively small minority of the global human population (the elite or the power elite), leading, they say, to very large and increasing wealth and income inequalities between the elite and the majority of the population. “Corporate capitalism” and “inverted totalitarianism” are terms used by the aforementioned activists and critics of capitalism to describe a capitalist marketplace—and society—characterized by the dominance of hierarchical, bureaucratic, large corporations, which are legally required to pursue profit without concern for social welfare.

The rise of giant multinational corporations has been a topic of concern among the aforementioned scholars, intellectuals and activists, who see the large corporation as leading to deep, structural erosion of such basic human rights and civil rights as equitable wealth and income distribution, equitable democratic political and socio-economic power representation and many other human rights and needs. They have pointed out that in their view large corporations create false needs in consumers and—they contend—have had a long history of interference in and distortion of the policies of sovereign nation states through high-priced legal lobbying and other almost always legal, powerful forms of influence peddling.

Anti-corporate-activists express the view that large corporations answer only to large shareholders, giving human rights issues, social justice issues, environmental issues and other issues of high significance to the bottom 99% of the global human population virtually no consideration. American political philosopher Jodi Dean says that contemporary economic and financial calamities have dispelled the notion that capitalism is a viable economic system, adding that “the fantasy that democracy exerts a force for economic justice has dissolved as the US government funnels trillions of dollars to banks and European central banks rig national governments and cut social programs to keep themselves afloat.”

People want health care and education to be social goods, not market commodities, so we can choose to put public goods back in public hands. People want the fruits of production and the yields of our generous planet to benefit everyone, rather than being siphoned up by the super-rich, so we can change tax laws and introduce potentially transformative measures like a universal basic income. People want to live in balance with the environment on which we all depend for our survival; so we can adopt regenerative agricultural solutions and even choose, as Ecuador did in 2008, to recognize in law, at the level of the nation’s constitution, that nature has “the right to exist, persist, maintain, and regenerate its vital cycles.”

Some critics cite capitalism’s inefficiency. They note a shift from pre-industrial reuse and thriftiness before capitalism to a consumer-based economy that pushes “ready-made” materials. It is argued that a sanitation industry arose under capitalism that deemed trash valueless—a significant break from the past when much “waste” was used and reused almost indefinitely. In the process, critics say, capitalism has created a profit driven system based on selling as many products as possible. Critics relate the “ready-made” trend to a growing garbage problem in which 4.5 pounds of trash are generated per person each day (compared to 2.7 pounds in 1960). Anti-capitalist groups with an emphasis on conservation include eco-socialists and social ecologists.

Planned obsolescence has been criticized as a wasteful practice under capitalism. By designing products to wear out faster than need be, new consumption is generated. This would benefit corporations by increasing sales while at the same time generating excessive waste. A well-known example is the charge that Apple designed its iPod to fail after 18 months. Critics view planned obsolescence as wasteful and an inefficient use of resources. Other authors such as Naomi Klein have criticized brand-based marketing for putting more emphasis on the company’s name-brand than on manufacturing products.

Market failure is a term used by economists to describe the condition where the allocation of goods and services by a market is not efficient. Keynesian economist Paul Krugman views this scenario in which individuals’ pursuit of self-interest leads to bad results for society as a whole. John Maynard Keynes preferred economic intervention by government to free markets. Some believe that the lack of perfect information and perfect competition in a free market is grounds for government intervention.

Economic Inequality Linked to Capitalism

In the United States, the shares of earnings and wealth of the households in the top 1 percent of the population in terms of income are 21 percent (in 2006) and 37 percent (in 2009), and 46% (2017) respectively. Critics, such as Ravi Batra, argue that the capitalist system has inherent biases favoring those who already possess greater resources. The inequality may be propagated through inheritance and economic policy. Rich people are in a position to give their children a better education and inherited wealth and that this can create or increase large differences in wealth between people who do not differ in ability or effort.

One study shows that in the United States 43.35% of the people in the Forbesmagazine “400 richest individuals” list were already rich enough at birth to qualify. Another study indicated that in the United States wealth, race and schooling are important to the inheritance of economic status, but that IQ is not a major contributor and the genetic transmission of IQ is even less important. Batra has argued that the tax and benefit legislation in the United States since the Reagan presidency has contributed greatly to the inequalities and economic problems and should be repealed.

The rich are getting a lot richer, while most of the rest of the population in the US is losing ground. Now the top 1% of Americans in terms of income receive the largest share of national income-the greatest since 1928. At the same time the share by the middle class is declining and the number of poor people is growing. Some hedge fund mangers made $4 billion annually, enough to pay the salaries of every public school teacher in New York City, according to Paul Buchheit of DePaul University. Today the average CEO’s pay is more than 350 times the average worker’s, whereas in 1965, it was only 25 times. According to the Wall Street Journal analysis of CEO compensation, the average CEO was paid $15 million in 2005 and the figure has increased dramatically. Goldman Sachs, one of the largest investment banks, just announced a new round of bumper bonus payments that will pay an average of $450,000 per person.

Linda McQuaig and Neil Brooks, authors of The Trouble with Billionaires,argue that increasing poverty due to economic inequality in the U.S. has detrimental effects on health and social conditions and undermines democracy. They cite the fact that while the U.S. has the most billionaires in the world, it ranks poorly in the Western world in terms of infant mortality, life expectancy, crime levels-particularly violent crime-and electoral participation.

Psychologists Ed Diener and Martin Seligman, in their article “Beyond Money: Toward An Economy of Well-Being,” published by the American Psychological Society, concluded “although economic output has risen steeply over the last decades, there has been no rise in life satisfaction during this period, and there has been a substantial increase in depression and distrust.” Diener and Seligman propose the creation of a national well-being index that includes such things as positive and negative emotions, engagement, purpose and meaning, optimism and trust, and a broad construct of life satisfaction as an equally important source for governments and leaders to develop economic and social policies.This contrasts significantly with the current popular measurement of financial wealth.

In their book, The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger, Professors Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, present data taken from multiple credible sources that show the gap between the poor and rich is the greatest in the U.S. among all developed nations; child well-being is the worst in the U.S. among all developed nations; and levels of trust among people in the U.S. among the worst of all developed nations.

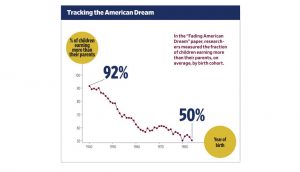

The Pew Foundation’s study, reported in the New York Times,concluded, “The chance that children of the poor or middle class will climb up the income ladder, has not changed significantly over the last three decades.” The Economist’sspecial report, “Inequality in America,” concluded, “The fruits of productivity gains have been skewed towards the highest earners and towards companies whose profits have reached record levels as a share of GDP.” I addressed the issue of income inequality in two previous articles in The Financial Post “How Income Inequality is Damaging Our Social Structure,” and “Will Income Inequality Cause Class Warfare?”

Kentaro Toyama, writing in The Atlantic, argues, “inequality grows naturally from unfettered capitalism…If free market capitalism works so well for every income level, why have so many people seen income pass them by with capitalism working more efficiently than ever before?”

Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz’s book, The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future,provides an insightful analysis of the problem of income inequality. Stiglitz argues free market capitalism isn’t working the way it was supposed to, for it is neither efficient nor stable. He also says that political systems are unfair, which compounds the problem. Stiglitz contends “We are no longer country of opportunity and that even our long-vaunted rule of law and system of justice have been compromised.”

Stiglitz echoes Toyama’s perspective: “America has always thought of itself as a land of equal opportunity…[it is] now a myth reinforced by anecdotes and stories, but not supported by the data. The chances of an American citizen making his way from the bottom to the top are less than those of citizens in other industrialized countries.” Stiglitz says there is a corresponding myth—rags to riches in three generations—that once a person reaches the top they have to continue to work hard to stay there or their descendants will move down. The reality is that children of wealthy people usually remain at the top.

One oftThe best selling books in the world currently is French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital In The 21st Century,which is a deep and thorough examination of economic inequality. Piety outlines at great length the growth of capital (ie., wealth) and its concentration in the hands of the 1% and how increasingly wealth is inherited, not created or distributed anew. The big idea of Capital in the Twenty-First Centuryis that we haven’t just gone back to nineteenth century levels of income inequality, we’re also on a path back to “patrimonial capitalism,” in which the commanding heights of the economy are controlled not by talented individuals but by family dynasties. His proposal to solve the income inequality issue is a progressive global wealth tax.

Public Perceptions of Capitalism and the Alternative–Socialism

A study by Harvard University showing that 51% of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 no longer support the system of capitalism, and asked whether the Democrats could embrace this fast-changing reality and stake out a clearer contrast to right-wing economics. It’s not only young voters who feel this way. A YouGov poll in 2015 found that 64% of Britons believe that capitalism is unfair, that it makes inequality worse. Even in the U.S., it’s as high as 55%. In Germany, a solid 77% are skeptical of capitalism. Meanwhile, a full three-quarters of people in major capitalist economies believe that big businesses are basically corrupt.

“For the first time in Gallup’s measurement over the past decade, Democrats have a more positive image of socialism than they do of capitalism,” Gallup notedin a summary of its findings, which come as socialist candidates continue to surpass expectations, garner widespread enthusiasm, and win elections across the nation.

“Attitudes toward socialism among Democrats have not changed materially since 2010, with 57 percent today having a positive view. The major change among Democrats has been a less upbeat attitude toward capitalism, dropping to 47 percent positive this year—lower than in any of the three previous measures.”

While Gallup’s latest survey was met with the typical and expected fear-mongering from right-wing defenders of capitalism—a system that has delivered immense wealth to the very top in the U.S. while leaving tens of millions of Americans impoverished and unable to afford basic necessities—progressives viewed the new numbers as a good sign but noted that they also show there is still tremendous work ahead.

As Common Dreams reported, a survey conducted by the progressive policy shop Data for Progress (DFP) last month showed that American voters are overwhelmingly supportive of “unabashedly left” policies like a federal jobs guarantee and ending cash bail.

Echoing Jones, DFP concluded that converting “favorable impressions into durable support will require activists and politicians to put these issues on the national agenda and make a forceful case for them over time.”

People want health care and education to be social goods, not market commodities, so we can choose to put public goods back in public hands. People want the fruits of production and the yields of our generous planet to benefit everyone, rather than being siphoned up by the super-rich, so we can change tax laws and introduce potentially transformative measures like a universal basic income. People want to live in balance with the environment on which we all depend for our survival; so we can adopt regenerative agricultural solutions and even choose, as Ecuador did in 2008, to recognize in law, at the level of the nation’s constitution, that nature has “the right to exist, persist, maintain, and regenerate its vital cycles.”

“Without us noticing, we are entering the post-capitalist era,” writes Paul Mason in the Guardian in an article entitled “The End of Capitalism Has Begun.” “At the heart of further change to come,” he continues, “is information technology, new ways of working and the sharing economy. The old ways will take a long while to disappear, but it’s time to be utopian.”

Former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis has claimed capitalism is coming to an end because it is making itself obsolete. The former economics professor told an audience at University College London that the rise of giant technology corporations and artificial intelligence will cause the current economic system to undermine itself. “So now there is no doubt capital is being socially produced, and the returns are being privatized. This with artificial intelligence is going to be the end of capitalism.”

Benjamin Freedman, of Harvard University, and author of The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth,describes how throughout American history, most people didn’t object to rich people getting richer as long as the middle class also benefitted, and that is not longer happening. According to a new study of CEOs by Jianyun Tang, Mary Crossan and W. Glenn Rowe, published in the Journal of Management Studies, dominant CEOs drive companies to extremes of performance and that boards of directors now rarely control those individuals.

America’s prevailing paradigm about its economy and business has been that money is a system of power and the more our lives depend on money, the greater our subservience to those who control the creation and allocation of money, argues, David Korten, author of the best seller When Corporations Rule the World. Korten raises legitimate questions such as “why do we assume that maximizing financial return maximizes the creation of real value?” and “what about the many fortunes built through financial speculation, fraud, government subsidies, the sale of harmful products and the abuse of monopoly power?”

Korten argues that there is a difference between real wealth which has intrinsic value (for example, land, food, knowledge, labor, water, the value of which is beyond price compared to phantom financial wealth, which exists on paper, that has no intrinsic value. Increasingly people are becoming wealthy through phantom financial means. He concludes that Wall Street and its international extensions have “generated total phantom wealth claims far in excess of the value of the real world’s wealth, thus creating expectations of future security and comfort that can never be fulfilled.”

Chris Meyer and Julia Kirby, writing in the Harvard Business Review Blogand authors of a book, Standing On The Sun, argue that “exclusive reliance on economic measurement has aligned Western Capitalism around managing the financial resources that don’t create value.”

That perspective was echoed in a research report entitled, Competition and Illicit Quality, by Victor Bennett of the USC Marshall School of Business, Lamar Pierce of Washington University’s Olin Business School, Jason Snyder of the UCLA Anderson School and Michael Toffel of Harvard Business School. They contend many companies in highly competitive industries are likely to bend the rules and cheat to keep their customers.

What Can Be Done?

In my National Post article, I said that the business world is fundamentally a community of people working together to create value for everyone in society, and that the pursuit by leaders of corporate and individual self-interest is a paradigm that has outlived its usefulness. That means a triple bottom line of profitability; social responsibility (both internally and externally) and sustainability must drive the capitalist engine.

In my Financial Postarticle, I described some of the commentary at the World Economic Forum, whichfocused on the need to restrict narrow self-interest at the cost of collective good, and greater social responsibility. At the crux of both the articles is the issue of a sustainable and equitable economy, and the fallacy that unrestrained economic growth, particularly growth that benefits the wealthiest individuals and corporations, can lead to improved human welfare–or basically, growth at all costs.

It is clear now that we have to not just recover from an economic recession, and now a pandemic but also reorganize the economy based on the quality of life rather than the quantity of life. The old model of business was based on a world with a small population, and a market economy as measured by GDP. But the world has changed dramatically. We live in a world with a large population and extensive capital infrastructures.

As part of the old business paradigm, we continue to perpetrate the myth, particularly in the U.S., of individualism. That every individual and company has to struggle to make it on its own. So we’re taught to embrace the notion of man being a Lone Ranger, coming together with others only to accomplish self-interest purpose. Yet, as we know from brain science, our brains have evolved over millions of years in a social context of interdependence. We are “wired” to be social and seek out and develop social connections.

What’s the difference? Steven Pressman says one thing: Government. All the handouts, tax benefits, subsidies and rebates that transfer money into middle-class pockets. Without government help, Canada’s and Europe’s middle class would be endangered. Pressman, in his book, The Decline of the Middle Class: An International Perspective says says that in a modern global economy, the middle class can only be self-sustaining with active government programs, because the free market produces great inequalities of income. He says that contrary to popular belief, the countries that are doing well are the ones that have robust tax-and-spend programs. And an interesting caveat to Pressman’s assertion is that the countries that are helping their middle class the most are not doing so at the expense of the wealthy but at the expense of the poor.

Scandinavian or Nordic Socialism/Capitalism

The Nordic model (also called Nordic capitalism or Nordic social democracy) refers to the economic and social policies common to the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Sweden). This includes an underlying social foundation of a comprehensive welfare state and collective bargaining at the national level with a high percentage of workers belonging to labor unions combined with the tenets of free market capitalism; and state provision of free education and free healthcare as well as generous, guaranteed pension payments for retirees funded by taxation. The Nordic model began to earn attention after World War II.

Canada, New Zealand and the U.K. have some elements similar to Nordic capitalism. Although there are significant differences among the Nordic countries, they all share some common traits. These include support for a “universalist” welfare state aimed specifically at enhancing individual autonomy and promoting social mobility; a corporatist system involving a tripartite arrangement where representatives of labor and employers negotiate wages and labor market policy mediated by the government; and a commitment to widespread private ownership, free markets and free trade.

Each of the Nordic countries has its own economic and social models, sometimes with large differences from its neighbors. According to sociologist Lane Kenworthy, in the context of the Nordic model “social democracy” refers to a set of policies for promoting economic security and opportunity within the framework of capitalism rather than a replacement for capitalism. In the case of Norway, being the state owner of key industrial sectors, it has been described as XXI century socialism.

Post-Capitalism and Work

Paul Mason in his book Post-Capitalism: A Guide to our Future, Mason argues that “work” is becoming redundant. He sees the battle between the hierarchy and horizontal forms of organization as ending in favor of the latter (the Internet), arguing further than labor in the form of machinic procedural or digital automation reduces the amount of living labor required for social progress, so the need for work of any sort diminishes. This creates a crisis for capitalism, Mason says, as the rate of profit steeply declines and goods and services rapidly become cheaper. Mason cites network theoreticians like Yochai Benkler and management guru Peter Drucker to argue that the generation of rich data is something that can be tuned towards an alternative to capitalism. Markets and states will slowly dissolve he says.

Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, in their book, Inventing the Future: Post-Capitalism and a World Without Work argue that a workless future is only something that can be the result of intense political struggle and emancipatory technological advances. They argue that rather than resist automation and the destruction of jobs it entails, we must instead demand more automation and more machines, and instead of demanding more work for people, we should be demanding less, and aim for a “synthetic” freedom which seeks to secure our material needs and challenge social constraints and norms. Pivotal ot this is the need for a universal basic income.

While the likelihood of a complete abandonment of capitalism in not likely in the short term, particularly in the US, critics and experts have suggested taking bold steps to redefine the paradigm of economic life as reflected in the purpose of business enterprises.

Alternatives to Our Current Form of Capitalism

The alternatives to consumeristic predatory capitalism are not mysterious, nebulous, or theoretical. They are already operating and established in many ways, on both large and small scales. Some examples include:

- Dozens of countries (including most European countries, but also Canada and Japan) operate more or less as social democracies, and manage to provide healthcare, education, public safety, and other benefits to all of their citizens. Taxes are higher, but income and social inequality are lower. Social trust and happiness tend to be higher in functioning social democracies, which has a lot to do with more income equality.

- Large-scale cooperatives such as the Mondragon Corporation provides models for how to simultaneously achieve business excellence and social responsibility.

- Open-Source Ecology and their audacious Global Village Construction Set project provide a window into the future of open-source production and distribution methods (beyond information products and into the realm of functioning machines).

A new model of business, and indeed free market capitalism, is necessary because the old one is broken and out of date.In a white paper, “The Game Has Changed: A New Paradigm for Stakeholder Engagement,”produced for the Cornell University Center for Hospitality Research, author Mary Beth McEuen, Vice President of The Maritz Institute, says “In the ‘new normal’ environment, businesses must do more than merely offer a good product or serve to create value…customers, sales partners, or employees, all are looking for relationships with organizations they can trust…organizations that care…organizations that align with their own values. Instead of viewing people as a means to profit contemporary businesses must see their customers and clients as stakeholders in creating shared value.”

McEuen argues that traditional business beliefs that brought success in the past will not bring success in the future. People are very skeptical about businesses and a new approach is needed.Despite the rapid significant changes that have occurred in the world of business, the management philosophy has been anchored in the classical economics view of the company merely as a economic entity that has a goal of appropriating the greatest possible value from all its constituencies. In this view, McEuen contends, management’s core challenge has been to tighten the company’s hold over its stakeholders, find ways to keep competitors at bay, protect the firm’s strategic advantage and allow it to benefit maximally particularly for shareholders. The problem with this philosophy is that it is based on industrial-era paradigms that simply will not work in the new business and social environments.

In my National Post article, I said that the business world is fundamentally a community of people working together to create value for everyone in society, and that the pursuit by leaders of corporate and individual self-interest is a paradigm that has outlived its usefulness. That means a triple bottom line of profitability; social responsibility (both internally and externally) and sustainabililty must drive the capitalist engine. In my Financial Post article, I described some of the commentary at the World Economic Forum, which focused on the need to restrict narrow self-interest at the cost of collective good, and greater social responsibility. At the crux of both the articles is the issue of a sustainable and equitable economy, and the fallacy that unrestrained economic growth, particularly growth that benefits the wealthiest individuals and corporations, can lead to improved human welfare–or basically, growth at all costs.

It is clear now that we have to not just recover from an economic recession, and pandemic, but also reorganize the economy based on the quality of life rather than the quantity of life. The old model of business was based on a world with a small population, and a market economy as measured by GDP. But the world has changed dramatically. We live in a world with a large population and extensive capital infrastructures. Material consumption and GDP are merely means to the end of improving our well being, not ends in themselves. Material consumption beyond mere need actually can reduce our well being. From a management perspective, predominant theories of human behavior contained in business strategy and management are still mired in century old theories of transactional exchange and simple Skinnerian behavioral theories, ignoring the considerable neuroscience and human behavior research in the last decade.

For example, many business leaders still believe that people make decisions on the basis of rationality and logic, when we know from brain science that emotions always play a pivotal role.A new model of economy based on the goal of sustainable human well being for all people, not just a few, is needed, measured by factors that show sustainability, social equality and economic efficiency.This presents a real challenge for the proponents of the current free market system, which would mean implementing economic policy on the basis of issues such as social fairness—something that is often attacked by business leaders and politicians being either socialistic or communistic. Yet, it is clear that the market economy has actually contributed to declining levels of social fairness in our society and increasing numbers of employees and customers are disengaging from businesses.

A new form of capitalism and business would move away from a zero-sum game to one where every stakeholder benefits without trade-offs and where there is a higher purpose that serves as a motivational beacon for the leaders and culture. The new business norm, MCEuen argues, calls for a new set of capabilities within organizations, including social networks as a means of getting work done, deeply engaging knowledge workers in meaningful work and relating to customers in ways that are more personal. McEuen describes the new business norm, which has, as it’s conceptual foundation, “shared value”—where the total pool of economic and social value is expanded.

A recent World Economic Forum produced the “Davis Manifesto” for a better kind of capitalism, which proposed some fundamental changes, although critics say it’s still based on the current paradigm of economic life. Here are the principles:

- A company serves its customers by providing a value proposition that best meets their needs. It accepts and supports fair competition and a level playing field. It has zero tolerance for corruption. It keeps the digital ecosystem in which it operates reliable and trustworthy. It makes customers fully aware of the functionality of its products and services, including adverse implications or negative externalities.

- A company treats its people with dignity and respect. It honors diversity and strives for continuous improvements in working conditions and employee well-being. In a world of rapid change, a company fosters continued employability through ongoing upskilling and reskilling.

- A company considers its suppliers as true partners in value creation. It provides a fair chance to new market entrants. It integrates respect for human rights into the entire supply chain.

- A company serves society at large through its activities, supports the communities in which it works, and pays its fair share of taxes. It ensures the safe, ethical and efficient use of data. It acts as a steward of the environmental and material universe for future generations. It consciously protects our biosphere and champions a circular, shared and regenerative economy. It continuously expands the frontiers of knowledge, innovation and technology to improve people’s well-being.

- A company provides its shareholders with a return on investment that takes into account the incurred entrepreneurial risks and the need for continuous innovation and sustained investments. It responsibly manages near-term, medium-term and long-term value creation in pursuit of sustainable shareholder returns that do not sacrifice the future for the present.

- A company is more than an economic unit generating wealth. It fulfils human and societal aspirations as part of the broader social system. Performance must be measured not only on the return to shareholders, but also on how it achieves its environmental, social and good governance objectives. Executive remuneration should reflect stakeholder responsibility.

- A company that has a multinational scope of activities not only serves all those stakeholders who are directly engaged, but acts itself as a stakeholder – together with governments and civil society – of our global future. Corporate global citizenship requires a company to harness its core competencies, its entrepreneurship, skills and relevant resources in collaborative efforts with other companies and stakeholders to improve the state of the world.

Conclusion:

Capitalism, in the form that exists currently in the US is not sustainable, and the flaws and destructive qualities of it are becoming more apparent. It not longer serves the greater good nor does it sustain our environment for future generations. A change must come.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You WhereYou Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.