By Ray Williams

August 1, 2020

Incivility is on the rise in America. Why? Because of the recent recession and growing economic inequality? Because the undercurrent of racism and anti-immigrant beliefs are now more in the open? Because of the increased polarization of political parties and views? Because of the cancerous spread of misogynistic, homophobic and racist activity on social media? Or the example set by prominent political and business leaders and media? The result is increasing incidences of racism, vitriolic personal and online incendiary rhetoric and violence.

The lack of civility is a more insidious destructive force than civil war, and it is producing disastrous consequences, including gridlock, ineffective dispute resolution, polarization, and a decline in the quality of American life. Despite the legitimacy of contrary points of view on a variety of subjects, the vitriolic expression of those ideas as a persistent trend in American society has led to near absolute polarization in many legislative chambers, especially notable in the U.S. Congress.

As a consequence, the resolution of many of our most vexing problems has virtually ceased in favor of political one-upmanship. The net result is diminished productivity and the avoidance of responsive decision making.

In the place of productive dialogue leading to solutions, we observe political figures, members of the media, and others talking past each other as opposed to speaking with each other. Often their statements and attitudes are so rigid and antagonistic that future compromise becomes impossible. This leads to political inertia.

This crisis of incivility has become a chronic condition of public life. Consequently, incivility is compromising the success of American society and especially the viability of the democracy. Blame should not be assigned exclusively to political leaders however. The American people have become highly desensitized to behaviors that would have been outrageous not so many years ago. Indeed, in some circles this misconduct is cheered on and rewarded.

The following excerpt from the July 2016 Psychology Today article Is Civility Dead in America,seems particularly appropriate to this discussion: “Additionally, observational learning theory suggests that when leaders and those held in high esteem in our culture behave in uncivil ways, their behavior is modeled and repeated by others. For example, when celebrity CEOs, presidential candidates and other high ranking politicians, sportsstars, and Hollywood celebrities behave in uncivil ways (and get away with it) it gets modeled and thus repeated by others.”

Civility and Incivility Defined

Civility is defined as formal politeness and courtesy in behavior or speech. Synonyms are courtesy, good manners, consideration, respect, graciousness. It is a Latin word that originated in 509 BCE when Romans founded their republic, and kings were driven from the city. Civility appeared over time from the word civis, which means citizen, that is, only men with property. It matured into civitas, meaning the rights and duties of citizenship, and then civilitas appeared, meaning the art and science of citizenship.

The rights of citizenship meant that citizens met in an assembly where they voted for their leaders. It also meant the right to be governed under laws that they voted for and not subject to the whims of despots. Their duties were clear–serving with other citizens in centuries, cohorts, and legions, and providing for their own equipment–shields, swords, javelins, and helmets.

The Romans, in creating an empire that expanded around the world put great emphasis on civil virtue. The Romans believed in honest debate, civility in the streets and treating adversaries with respect, even if defeating them in battle. Historians looking at the fall of the Roman Empire have tried to find reasons why the great Empire failed. Many see the loss of the civil society as a major reason for the fall of the Romans. People stopped treating each other with respect. The Empire itself stopped treating those they conquered with respect. What was once a society of mutual respect for all became a society of overconfidence of complacency. The very values that made the Roman Empire great were the very values that were left behind.

The English word civility comes from the French word civilité. The Norman and Plantagenet kings were French. The time period was the twelfth to the fifteenth century. Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry II’s wife and mother of Richard the Lion Heart and King John, brought civility to the English. But the word had changed. Citizens and the Republic were missing and Europe now had lords and vassals. Civility became the proper conduct between lords and free men who served them– deference, cooperation, service, reciprocal rights and duties, and proper speech and dress. Civility became a social, political, that is, courtly word.

Magna Carta was an agreement between the king and his vassals. Then during the Renaissance, the Age of Science, and the Enlightenment–a period of three hundred years–the understanding of civility reached new levels. The Renaissance was an age of humanism where society focused on broad human and humanistic concerns. Being human and human hearted, creating an elevated sense of humanity, and celebrating human achievements became the central focus of communities in both a social and civil way. Republican civility reappeared and flourished in the Italian city-states and republics. The communes throughout Europe had special civic and economical privileges. The educated gentleman was characterized as:

- Having polished manners, courtly etiquette, fine speech,

- Having a nobility of bearing and attitude,

- Having a love of beauty, and being sensitive, and respectful to their class and to others,

- Being sophisticated and international (European), educated in the humanities,

- Being inspired by honor and duty, deliberate and liberal in thought, a gentleman.

At this time, a wisdom developed over the importance of civility. A Latin phrase was used–civilitas. The phrase meant that the culture of civility was the anchor of our humanity. The practice of civility holds us to our human heartedness, the essence of our humanity. It meant humans acting their best, their most noble selves, acting civilized. The late eighteenth century experienced the American Revolution and the French Revolution, the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. All of these were part of a wider movement that demanded rights for everyone grounded in the rights of citizenship.

Presidential democracy and parliamentary democracy appeared in the nineteenth century and the franchise for women was won in the twentieth. The greatest achievement of the twentieth century was the UN’s adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Add to these magnificent achievements The Discovery of the Child, and the idea of civility seemed complete:

- All the human family are citizens of the Earth.

- Civility is the art of citizenship; it is the recognition of the reciprocal rights and duties of those who govern and are governed.

- It is the proper understanding of the human condition, of human relationships, and the power of human heartedness.

- It recognizes the qualities of humanness that bond us together in the human household and the human family.

- It recognizes the universal human rights of others.

- It is formed in the proper study of the humanities– those studies that explore and honor the human struggle and the human condition.

Characteristics of Civility and Incivility

Here are some examples of uncivil and civil behavior:

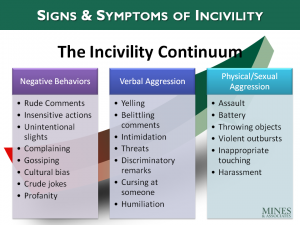

Incivility:

- Interrupting and talking over others who have the floor.

- Overgeneralizing and offering dispositional character criticisms and attributions.

- Using language that is perceived as being aggressive, sarcastic, or demeaning

- Speaking too often or for too long.

- Engaging in disrespectful non-verbal behaviors (e.g., eye rolling, loud sighs).

- Offering false praise or disingenuous comments (e.g., “With all due respect but…”).

- Losing one’s temper or yelling at someone in public.

- Rude or obnoxious behaviour.

- Badgering or back-stabbing.

- Withholding important information.

- Sabotaging a project or damaging someone’s reputation.

- Arriving late to a meeting.

- Checking email or texting during a meeting.

- Ignoring or interrupting someone.

- Physically “cutting off”or jostling someone (as a pedestrian, cyclist or car driver).

- making rude, misogynistic, homophobic and personally insulting remarks (verbally or in writing).

- making verbal or physical threats of violence.

Civility

- Thinking before speaking.

- Using respectful and “non-violent” language.

- Focus on facts rather than beliefs and opinions.

- Focus on the common good rather than individual agendas.

- Disagreeing with others respectfully.

- An openness to others without hostility.

- Respectfulness of diverse views and groups.

- A spirit of collegiality.

- Offering productive and corrective feedback to those who behave in demeaning, insulting, disrespectful, and discriminatory ways.

- Being physical courteous and helpful to others.

- Giving positive feedback to others regarding their civil behaviours.

Why is Civility So Important?

Jim Taylor, a psychologist at the University of San Francisco, writing in the Huffington Post contends that “Civility is about something far more important than how people comport themselves with others. Rather, civility is an expression of a fundamental understanding and respect for the laws, rules, and norms (written and implicit) that guide its citizens in understanding what is acceptable and unacceptable behavior. For a society to function, people must be willing to accept those strictures. Though still in the distance, the loss of civility is a step toward anarchy, where anything goes; you can say or do anything, regardless of the consequences.”

Civility is the action of working together productively to reach a common goal, and often with beneficent purposes. Some definitions conflate civility with politeness, which suggests disengaging with others so as not to offend (“roll over and play dead”. The notion of positively constructive civility suggests robust, even passionate, engagement framed in respect of differing views.

Community, choices, conscience, character are all elements directly related to civility. Civility is more than just having manners, because it involves developing a civil attitude and civil responsibility. Civility often forms more meaningful friendships and relationships, with an underlying tone of civic duty to help more than the sum of its whole.

The Causes of Incivility

There are a number of interrelated social, economic and psychological causes for incivility. Here are a few:

- External threats (real or imagined) creating fear. The most obvious example is COVID-19 pandemic, but could include the perceived threats of immigrants, criminals/terrorists, and natural disasters.

- Economic uncertainty. Many Americans are stressed these days, given the economic situation and uncertainties about the future. They’re concerned about their jobs and families; they’re working longer and harder than ever or not at all, and they are not sure when things will get better.

- The example set by political and business leaders. When our leaders exhibit uncivil behavior, it gives license for others to do the same.

- Economic inequality. Inequality is increasing in the U.S. to unheard of levels, where the 1% are accruing most of the benefits of the booming economy, at the expense of the poor and middle classes.

- The cult of individualism and lack of restraint—“I’ll do it my way.” When we care little about what others think of us, we think little of them. We feel less bound by respect and restraint. The cult of individualism, more prominent in the U.S. than anywhere else, has reinforced the beliefs that an individual’s misfortune is their fault, and that society doesn’t have an obligation to ensure basic social welfare for all its citizens.

- Inflated self-worth: People who are self-absorbed don’t value others except as a means to fulfill needs and desires.

- Low self-worth. People who are insecure may become defensive and hostile.

- Materialism—The quest for money and possessions to be happier often is futile and frustrating, resulting in less kindness to others.

- Injustice—People who perceive they have been treated unfairly can become demoralized, depressed, indignant or outraged. The injustice may be a feeling of envy—it’s unfair that you are smarter, better looking, wealthier than I am.

- Anonymity of social media, where people feel they have license to be uncivil and hide behind the curtain of anonymity.

- Disintegration of community and increase in isolation. Add to that the increasing phenomena of loneliness and depression in the US and you have a double whammy.

Incivility Online

There is growing evidence that “online incivility” is spreading across social networking sites (SNS) making them a potentially hostile environment for users. The Pew Research Center (PRC) has documented the rising incidence of incivility in SNS-based interactions: for example, 73% of online adults have seen someone being harassed in some way in SNS, and 40% have personally experienced it. Also, 92% of Internet users agreed that SNS-mediated interaction allows people to be more rude and aggressive, compared with their offline experiences.

“Trolls are portrayed as aberrational and antithetical to how normal people converse with each other. And that could not be further from the truth,” says Whitney Phillips, a literature professor at Mercer University and the author of This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship Between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. “These are mostly normal people who do things that seem fun at the time that have huge implications. You want to say this is the bad guys,but it’s a problem of us.”

Cellphones are another target for incivility researchers. While most users no longer feel the need to shout into their phones, they may be so wrapped up “in their own little bubbles” that they don’t realize they’re blocking a sidewalk or holding up a line, says psychologist Veronica V. Galván.

The Facebook “Pages” and the Twitter accounts of actors of public interest such as political parties, magazines, and celebrities provide a typical setting for online incivility.

A Pew Research Centre survey published two years ago found that 70% of 18-to-24-year-olds who use the Internet had experienced harassment, and 26% of women that age said they’d been stalked online. This is exactly what trolls want. A 2014 study published in the psychology journal Personality and Individual Differences found that the approximately 25% Internet users who self-identified as trolls scored extremely high in the dark tetrad of personality narcissism.

The News Media Fans the Flames of Incivility

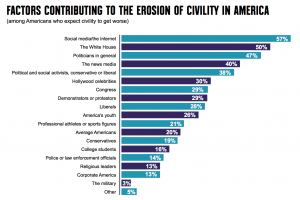

Many mainstream media outlets have changed from reporting the factual news and honest commentary to either tools of the government or political parties, reporting lies and false information. FOX News has been an example. Add to that the fact that a large percentage of the American public receives their news from unverified reports on Facebook, and the results can fuel incivility.

Research Evidence for Increasing Incivility

A Google Scholar search of the term workplace incivility returned 23 works published from the years 1996 through 2000. Contrast that with the last half decade (2011 through 2015), which saw 1,700 articles published on this topic.

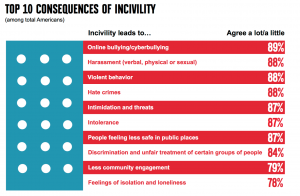

Here is some other data to illustrate the increasing incidents of incivility:

- Research has linked political incivility to reduced trust in the legitimacy of political candidates, political polarization, and policy gridlock.

- The most recent poll by Weber Shandwick, reported nearly 50% of those surveyed said they were withdrawing from the basic tenants of democracy—government and politics—because of incivility and bullying.

- Half of American parents (50%) report that their children have experienced incivility at school and nearly half of Americans twenty years and older (45%) say that they’d be afraid to be teenagers) today because of incivility’s frequent occurrence.

- Approximately seven in 10 Americans (69%) have either stopped buying from a company or have re-evaluated their opinions of a company because someone from that company was uncivil in their interaction. Further, nearly six in 10 (58%) have advised friends, family or co-workers not to buy certain products because of uncivil, rude or disrespectful behavior from the company or its representatives.

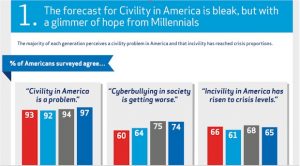

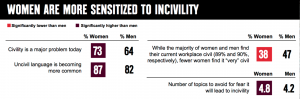

- Three-fourths of Americans believe incivility today has risen to crisis level, and 70% think civility has worsened since President Trump’s election.

- Recent survey results from the National Institute for Civil Discoursepoints out that 75 percent of Americans believe incivility is a major problem in society today.

- Not too long ago the fifth annual Civility in Americasurvey found over 90% of Americans feel civility is a problem in this country, and nearly two thirds believe incivility is at a crisis level.The survey also found that when it comes to the 83 million Millennials in this country: 74% believe the internet encourages uncivil behavior; 50% believe politicians are the main driver of incivility

- In a survey,Civility in Americaconducted by Weber Shandwick and Powell Tate with KRC Research, they revealed there is a severe civility deficit in our country. Sixty-nine percent of Americans blame the Internet and social media as the cause – not surprising given that one in four have experienced cyberbullying or incivility online.

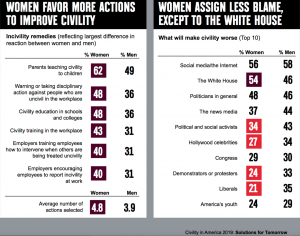

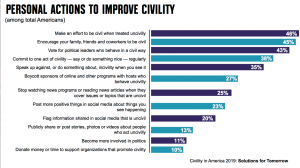

- In 2019, Weber Shandwick and Powell Tate, in partnership with KRC Research, released the results of their ninth Civility in America survey to assess America’s attitudes of and experiences with incivility. According to Andy Polansky, Weber Shandwick CEO, “It has never been more important to understand the sources and impact of America’s eroding state of public discourse.”

- According to the Gallup 2019 Confidence in Institutions Poll, 48 percent of people have either “very little” or no confidence in television news, compared to 18 percent in 1993. Confidence in newspapers has also dipped, as 39 percent said they had “very little” or no confidence in newspapers in 2019 compared to only 17 percent as recently as 2003. Overall, TV News (18%), Newspapers (23%), and the US Congress (11%) had the lowest positive rankings of all institutions.

Being respectful lto people is not only about online, it’s has to do with our way of life and how we treat people offline too. In this 2019 Pew poll of Americans surveyed:

- 84 percent have personally experienced incivility.

- 59 percent quit paying attention to politics because of incivility.

- 53 percent have stopped buying from a company because of uncivil representatives.

- 34 percent have experienced incivility at work.

- 25 percent have experienced cyberbullying or incivility online, upnearly three times from 2011.

- 25 percent of parents have transferred children to different schools because of incivility.

Incivility in the Workplace

According to a survey by Zogby International, almost 50% of the U.S. workers report they have experienced or witnessed some kind of bullying—verbal abuse insults, threats, screaming, sarcasm or ostracism. One study by John Medina showed that workers stressed by bullying performed 50% worse on cognitive tests. Other studies estimate the financial costs of bullying in the workplace at more than $200 billion per year. The consequences of such bullying have spread to families and other institutions and cost organizations reduced creativity, low morale and increased turnover. According to the Workplace Bullying Institute, 40% of the targets of bullying never told their employers, and of those that did, 62% reported that they were ignored.

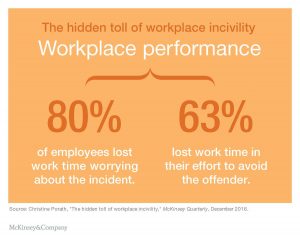

“Workplace incivility has doubled over the past two decades and has an average annual impact on companies of $14,000 per employee due to loss of production and work time,” according to a new study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology.

Uncivil behaviors at work — put-downs, sarcasm and other condescending comments — tend to have a contagious effect, according to a new studyby a management professor at the University of Arkansas and several colleagues. According to the U.S.Department of Labor, there are about 1.8 million acts of physical violence in the American workplace in any given year.

Rudeness at work is contagious, says a studyby three psychologists at Lund University in Sweden. They surveyed nearly 6,000 people on the social climate in the workplace. Their studies show that being subjected to rudeness is a major reason for dissatisfaction at work and that unpleasant behaviour spreads if nothing is done about it.

Russell Johnson, an associate professor of management at the Eli Broad College of Business at Michigan State University, explainsthe subtlety of incivility, noting that it “does not involve openly hostile behavior, threats, or sabotage. As such, incivility is more benign and does not warrant the same legal attention or formal sanctions as other forms of mistreatment. Yet, it is a relatively frequent, low-intensity negative behavior that has a substantial impact on employees”.

It could be as simple as a sarcastic reply to a co-worker’s comment during a meeting. Or a rude sentence in a poorly thought-out e-mail. Johnson believes our increasing dependence on e-mail contributes to the rise in incivility. “I think our communication is less direct,” he said. “A lot of our communication is done over phone or e-mail. It’s hard to understand the intent of an e-mail without any additional language or social or facial cues to go along with it. That creates more ambiguity. And it makes it easier to be uncivil when you’re not face-to-face with someone.”

And one of the big problems is that incivility is sneaky. It’s not in-your-face, like harassment or bullying. Johnson’s study notes that “because incivility (a) reflects a mild form of mistreatment that is likely to go unpunished, (b) is not limited to interactions with those in authority positions, and (c) is easily denied and therefore excused, it occurs more frequently than other forms of mistreatment and, thus, has the potential to create a noxious social environment.”

This comes into particular focus with a new study in the Journal of Management. A research teamled by Sandy Lim from the National University of Singapore finds that when people have hostile experiences at work, they’re more likely to be angry or withdrawn when they get home. “Our findings show that the experience of incivility was positively related to feelings of hostility, which was in turn associated with increased angry family behaviors, as rated by spouses,” Lim and her colleagues write.

“This suggests that individual emotions do fluctuate on a day-to-day basis in response to incivility at work, and these emotional responses can have consequences even in the home environment.” The research reinforces the link between between how being in a hostile environment at work can transfer to hostility at home.

The Prevailing Business Model Business Leaders Contribute to the Problem

A graphic example of incivility is Trump ’s Apprentice TV show, where people eagerly used to await Trump’s now famous edict—“you’re fired”—as some kind of pleasure.

Witness smack-talking Oracle co-founder and CEO Larry Ellison calling the HP board “idiots” for firing Mark Hurd, and ridiculing SAP co-founder Hass Plattner’s “wild Einstein hair” in an email to the Wall Street Journal or even dissing Bill Gates as not being so smart, as reported by Brad Stone and Aaron Ricadela, writing in Bloomsberg BusinessWeek.

Or the legendary stories of Silicon Valley’s success stories like Travis Kalalnick who was forced to resign as CEO because he damaged Uber’s reputation with revelations of sexual harassment in its offices, allegations of trade secrets theft and a federal investigation into efforts to mislead local government regulators. And Kalanick is not an exception in Silicon Valley’s tech industry.

Stanley Bing wrote in the early 1990s: “So it is today, where bullying behavior is encouraged and rewarded in range of business enterprises. The style itself is applauded in boardrooms and in business publications like Business Week, as “tough,” “no nonsense,” “hard as nails.” When you see these code words, you know you’re dealing with the bully boss…thanks to the admiration in which bully management is held in American business and academic gurus who perpetuate the techniques.”

Little is said in the U.S. media or public discussion about how the continuing obsession with short-term profits and the awarding of exorbitant executive pay lay the foundation for a surge in abusive behavior in the workplace to begin with, let alone how the introduction of best-practices of flexible employment, outsourcing of traditional company tasks, and the recourse to workers reclassified as “independent contractors” have opened the door to “management by terror” Reid contends. These changes compounded worker vulnerability in those workplaces already left to the tender mercies of “at-will employment,” a workplace regime dating from the19th century and unique to the U.S.

The Bystander Problem

When an act of incivility occurs, whether it’s road rage, uncivil behavior on a subway or street or in the workplace or school, there’s increasing evidence that people witnessing those events are increasingly less willing to intervene. This is often referred to as the bystander effect.

What separates those who speak up from those who stay silent? On the one hand, you might hypothesize that people who are more aggressive or hostile by nature are more likely to openly challenge a stranger. On the other hand, speaking out against injustice could be seen in a more positive light, as an act of maturity. Emerging research supports the latter idea — that people who stand up to incivility have a strong sense of altruism, combined with self-confidence. Understanding what motivates these heroic individuals could lead to more effective ways of curbing everyday immoral behavior.

Psychologist Alexandrina Moisuc and her colleagues recently published findings from three studies looking at the personality profile possessed by people who say they would intervene in the face of bad behavior. Although there has been extensive research on how situational factors can impact people’s motivation to intervene (i.e. research on the bystander effect), there have been fewer studies looking at the role of personality.

The researchers tested two competing and equally plausible theories about who stands up: the “bitter complainer” versus the “well-adjusted leader.” The “bitter complainer” theory suggests that hostile, aggressive, and insecure people are more likely to become vigilantes out of a desire to unleash displaced frustration onto an unsuspecting target. In contrast, the “well-adjusted leader” theory takes the view that people who intervene are more likely to be confident, stable, and mature.

Overall, the findings seemed to support the “well-adjusted leader” theory rather than the “bitter complainer” hypothesis. People who said they would react to the behaviors depicted in the videos felt more moral outrage (i.e. stronger feelings of anger and disgust), but they did not appear to be inherently more aggressive than other people, as measured by a personality scale. Instead, they scored higher on a measure of altruism, suggesting that their motivation to act was coming from a place of wanting to help others rather than harm the person engaging in the bad behavior.

If anything, Moisuc and her colleagues seem to have found that people who stand up in the face of uncivil behaviors are the opposite of complainers. Instead they seem to possess traits that characterize upstanding citizens: a strong desire to help others, self-confidence, security in one’s place in society, and maturity in handling their own emotions. Other research has supported the idea that people who intervene, have a more positive outlook on others. Psychologists Aneeta Rattan and Carol Dweck found that people who believe that others have the capacity to change are more likely to confront prejudice.

The Experts Weigh In

Pier M. Forni, an award-winning professor of Italian Literature and founder of The Civility Initiative at Johns Hopkins University and author of The Civility Solution: What to Do When People are Rude says Incivility and bullying behavior is also often a precursor to physical violence. Forni says feelings of insecurity only exacerbate the problem. “When we are insecure or not sure of ourselves for whatever the reason because the economy is bad, or we think we are going to lose our jobs … very often we shift the burden of that insecurity upon others in the form of hostility,” he says. “It is the kick-the-dog syndrome. You make an innocent pay for how badly you feel in order to find some kind of relief.”

“How in the world can we stop bullying in schools, in the workplace, in politics, when it is so close to our national character right now?” asks Dr. Gary Namie, a psychologist and cofounder of the Workplace Bullying Institute.

Writing in the Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies, Roddey Reid, a professor of cultural studies at the University of California contends, “Although a universal problem, bullying enjoys a virulence and prevalence in contemporary U.S. culture virtually unmatched anywhere else in terms of its reach, depth, and legitimacy. Unlike in many European nations and Canada it is not illegal in the U.S.” Reid argues that Americans should not be surprised at the levels of incivility. It’s not like there wasn’t ample warning. “There’s so much macho bluster, strutting around, talking tough, he says.

But following close behind came the actions: fire-bombings of abortion clinics, serial capital executions, gay bashings—not to mention “three-strikes” laws and mandatory sentencing that send citizens off to long prison terms for petty drug offenses, tripling the U.S. prison population within twenty years. Next to come in for brutal treatment were the schools and workplaces: from the presence of police in hallways and zero tolerance drug tests to factory closings and the downsizing of middle-management, to the cutting and privatization of public services and government programs. Even the Post Office became a ‘profit centre of excellence’ meant to compete with private sector enterprises; it also became a center of workplace violence and shootings,” Reid says.

In the The Case for Civility: And Why Our Future Depends On It well-known author Os Guinness argues that civility needs to be rebuilt in the US if it is to survive as a democracy: “Civility must truly be restored. It is not to be confused with niceness and mere etiquette or dismissed as squeamishness about differences. It is a tough, robust, substantive concept… and a manner of conduct that will be decisive for the future of the American republic”.

But to dismiss signs of courtesy as mere symbols and to argue that what matters is not the outward trappings misses the point, said Richard Boyd, an associate professor of government at Georgetown University. “To fail to be civil to someone — to treat them harshly, rudely or condescendingly — is not only to be guilty of bad manners,” he wrote in a 2006 article, “The Value of Civility?” for the journal Urban Studies. “It also, and more ominously, signals a disdain or contempt for them as moral beings. Treating someone rudely, brusquely or condescendingly says loudly and clearly that you do not regard her as your equal.”

A series of 2016 studies conducted by the Journal of Applied Psychologyfound that, like the common cold, rudeness is easily contracted, and exposure to one episode can have long-lasting effects. Not only can anyone be a carrier, but also “rudeness activates a semantic network of related concepts in individuals’ minds, and that this activation influences individuals’ hostile behaviors.” When we’re around rudeness, we may even misinterpret ambiguous behavior as hostile, exhibit negative facial expressions and body language, and then exact revenge.

“When you experience rudeness, it makes rudeness more noticeable,” said lead researcher Trevor Foulk. “You’ll see more rudeness even if it’s not there.”

Incivility in Political Life

“Crude, rude and obnoxious behavior has replaced good manners and it hurts our politics and culture.” A U.S. News & World Report came out with an article on “The American Uncivil Wars” that confronts the amazingly rude state of affairs in which young Americans are in today and concluded incivility is one of the greatest problems that America is faced with.

Nowhere is the problem of incivility more prominent than in politics with political discourse between candidates degenerating into attack ads and worse. The NAACP published a report called “Tea Party Nationalism,” exposing what it calls links between various Tea Party organizations and racist hate groups in the United States, such as white-supremacist groups, anti-immigrant organizations and militias. The NAACP report, which counts among its authors, Leonard Zeskind, one of the country’s foremost scholars of white nationalism, says the right wing portion of the Republican Party has become a site for recruitment by white supremacists and others. There has been a significant increase in the number of people becoming active members of racist white nationalist or neo-Nazi groups, which make little effort to suppress their incivility.

Incivility sneaks into your subconscious. Research experiments at the University of Florida show that those simply around incivility are more likely to have dysfunctional and aggressive thoughts, although they may be unaware of the connection. As a mathematical modeldeveloped by Yale psychologists Adam Bear and David Rand showed, people who are typically surrounded by jerks learn intuitively to be selfish and not to deliberate over their actions. They wind up acting selfishly even when cooperating would pay off, precisely because they do not stop to think. Our environment rubs off on us, and if our environment is toxic, we can expect to stay somewhat sick and to pass it on to others.

None of this bodes well for the problem solving America needs to address the daunting economic, health care, human, and international relations issues we face. Will incivility jeopardize deals that would help America and its people?

Politicians’ and other leaders’ uncivil behavior spreads. In several research studies over 25% blame their bad behavior on their leaders. They are simply role modeling what they have learned.

A campaign that reeks of rudeness rubs off on more than the candidates and their inner circles though. We each have a much bigger effect on one another’s emotions than we might think—for better and for worse. In their book Connected, Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler show how happiness spreads not only among pairs of people but also between a person and his friends, his friends’ friends, and their friends. Civility and incivility spread the same way. A seemingly small act of kindness or rudeness ripples across communities, affecting people in our network with whom we may or may not interact directly.

They say: “We are primed to be more uncivil after this election—even if we do not realize it. Those that feel disrespected may be frustrated, disappointed or fearful of where we stand in the pecking order. Tens of millions may feel belittled based on race, religion, culture or gender. We may have a chip on our shoulder, and carry those feelings into interactions with others. We are not poised to pitch in. We are primed to hold back.”

In a series of experiments by Diana Mutz and Byron Reeves, incivility in political discourse had adverse effects on the public’s regard for politics. Not only were attitudes toward politicians and Congress influenced, support for the institutions of government also were affected.

Incivility is a highly infective and invasive, a pathogen that can quickly and silently sicken a team, political party, organization and country. Most people may not realize just how susceptible they are and the extent to which they are carriers of it.

Donald Trump has used incivility to support his presidential campaign and political agenda, which warrant far more alarm than suggested by terms such as “ill-mannered.” More than other candidates, Trump not only showcased and appropriated “incivility” in his public appearances as a mark of solidarity with many of his white male followers, he tapped into their resentment and transformed their misery into a racist, bigoted, misogynist and ultra-nationalist appeal to the darkest forces of authoritarianism. Yet millions of Americans decided to live in Trumpland, as David Remnick observed in the New Yorker immediately upon Trump’s election, this represents more than a tragedy in the making.

Clearly, Trump’s embrace of “incivility” was a winning strategy, one that not only signaled the degree to which the politics of extremism has moved from the fringes to the center of American life, but also one that turned politics into a spectacle that feeds the ratings of the mainstream media. Trump has turned politics into what Guy Debord once called a “perpetual motion machine” built on fear, anxiety, the war on terror, and a full-fledged attack on women, the welfare state, and poor minorities.

Tom Engelhardt has persuasively argued that Trump’s election may in time be viewed as a wholesale “regime change,” one that will alter the political and economic trajectory of the country, or what might otherwise be described as a paradigm shift toward an anti-democratic or authoritarian mode of governance. This is a change that points to a democracy spiraling out of control and a prescription for the unfolding of what Hannah Arendt once called the “dark times” associated with totalitarianism. Engelhardt writes: “Donald Trump’s administration, now filling up with racists, Islamophobes, Iranophobes, and assorted fellow billionaires, already has the feel of an increasingly militarized, autocratic government-in-the-making, favoring short-tempered, militaristic white guys who don’t take criticism lightly or react to speed bumps well. In addition, on January 20th, they will find themselves with immense repressive powers of every sort at their fingertips, powers ranging from torture to surveillance that were institutionalized in remarkable ways in the post-9/11 years with the rise of the national security state as a fourth branch of government, powers which some of them are clearly eager to test out.”

America has become a country motivated less by indignation, which can be used to address the underlying social, political and economic causes of social discontent, than by a galloping culture of individualized resentment, which personalizes problems and tends to seek vengeance on those individuals and groups viewed as a threat to American society.

Echoes of scapegoat-driven animosity can be heard in Trump’s “rhetorical cluster bombs,”in which he states publicly that he would like to punch protesters in the face, punish women who have abortions, bring back state-sanctioned torture and, of course, much more. Genuine civic attachments are now canceled out in the bombast of vileness and shame, which has been made into a national pastime and the central feature of a spectacularized politics.

The not-so-subtle signs of the culture of seething resentment and cruelty are everywhere, and not just in the proliferation of extremist commentators, belligerent nihilists and right-wing conspiracy types blathering over the airways, on talk radio and across various registers of screen culture. Young children, especially those whose parents are being targeted by Trump’s rhetoric, report being bullied more. Hate crimes are on the rise. And state-sanctioned violence is accelerating against Native Americans, black youth, and others now deemed unworthy or dangerous in Trump’s America. In the mainstream media, the endless and unapologetic peddling of lies becomes fodder for higher ratings, informed by a suffocating pastiche of talking heads, all of whom surrender to “the incontestable demands of quiet acceptance.”Politics has been reduced to the cult of the spectacle and a performative register of shock, but not merely,” as Neil Gabler observes, “in the name of entertainment. The framing mechanism that drives the mainstream media is a shark-like notion of competition that accentuates and accelerates hostility, insults and the politics of humiliation.”

It gets worse. In the age of a bullying Internet culture, the trolling community has now elected one of its own as president of the United States. As the apostle of publicity for publicity’s sake, Trump has adopted the practices of reality TV, building his reputation on insults, humiliation and a discourse of provocation and hate. According to the New York Times, even before the 2016 election Trump had used Twitter to insult at least 282 people, places and things. Not only has he honed the technique of trolling, he has also made it a crucial resource in upping the ratings for the mainstream media which, it seems, are insatiable when it comes to covering Trump’s insults.

Jared Keller captures perfectly the essence of Trump’s politics of trolling. He writes: “From the start, the Trump campaign has offered a tsunami of trolling, waves of provocative tweets and soundbites – from “build the wall” to ‘lock her up’ – designed to provoke maximum outrage, followed, when the resulting heat felt a bit too hot, by the classic schoolyard bully’s excuse: that it was merely ‘sarcasm’ or a ‘joke.’ In a way, it is. It’s just a joke with victims and consequences…. “

Historians of fascism such as Timothy Snyder and Robert O. Paxton have argued that Trump is not comparable to Hitler, but that there are sufficient similarities between them to warrant some concerns about surviving elements of a totalitarian past crystalizing into new forms in the United States. Paxton, in particular, argues that the Trump regime is closer to a plutocracy than to fascism. If Trump has his way, traditional state power will be replaced by the rule of major corporations and the financial elite, particularly ones that are loyal to him personally. We have already seen that the social cleansing and state violence inherent in totalitarianism has been amplified under Trump.

Both Hannah Arendt and Sheldon Wolin, the great historians of totalitarianism, argued that the dangerous conditions that produce totalitarianism are still with us. Wolin, in particular, insisted (in his book Democracy Incorporated) that the United States was evolving into an authoritarian society.

What’s To Be Done

We certainly appear to be living in terribly divisive and stressfultimes. Civility is hard to come by and it appears that everyone is angry, bitter, and frustrated being apparently free to share their upset with others in person and online. And it seems to be getting worse by the day.

While there are no easy answers to turning this trend around there are several psychological theories that are evidence based and adequately researched to help us better understand this phenomenon. And maybe if we can understand these theories a little bit better then we can be more thoughtful and strategic about our efforts to push back and work toward a more civil society.

First, we need to be mindful of observational learning. The well-known psychologist and Stanford Professor, Al Bandura, conducted numerous pioneering research studies that well demonstrate the power and influence of observing models and then acting as models do. So, when models who are high ranking politicians, Hollywood celebrities, sports stars, news leaders, and others who have the bullypulpit act in an uncivil, crude, demeaning, and hostile manner (and get away with it or are even rewarded for it), then others will feel free to act in a similar manner. Bad behavior is like a virus. If it is not contained, treated, or minimized then it will spread and infect others. Social media helps to spread these problematic behavioral viruses much more easily. So, when you have the interaction of social media with many awful models of terrible behavior to select from you ultimately have a perfect storm to spread the virus of bad behavior that you observe.

Second, we also need to be attentive to the frustration-aggression hypothesis. It suggests that ongoing frustration that is not resolved or settled can ignite into aggression when given an opportunity to do so. For example, this is why road rage incidents are more common in high traffic congested areas than in low traffic locations. Seething frustration can easily turn violent when sparked by a frustrating last straw incident.

A Consortium of university social scientists launched the Civility Project, at first just to study the problem. With the Beacon Journal’s involvement, their efforts have evolved to propose a set of standards which will soon become a public civility metric, inspired by Politifact’s Truth-o-meter.

The Consortium believes that to move away from incivility, we must:

- Set standards for civility in public discourse.

- Use these standards to identify and publicize moments of incivility in public discourse.

- From this perspective, the Consortium suggests there are pillars of civility: the ability to express an opinion while respecting other people; the ability to acknowledge the fact that opinions differ among people; and the ability to engage in constructive dialogue with other people.

- Civility disagrees with other opinions without disparaging other people or their opinions.

“A national public education campaign endorsed by political leaders, schools, PTAs and corporate America and distributed through the media might be an important first step towards bringing civility back to our shores,” argues Jack Leslie, Chairman of Weber Shandwick.

A second step may have to be legislation that proscribes incivility. In the U.S., 20 states are exploring legislation that would put bullying on the legal radar screen. In Canada, several provinces have passed legislation that addresses workplace bullying, although both countries are far behind some European nations and New Zealand.

How Else Can the Tide Be Changed?

Take the “civility challenge.” Americans can collectively recognize they have a civility problem, even a crisis, on their hands. Yet, while Americans can agree on what civility means, they don’t see themselves or even the people close to them as part of the problem. Each person should take a closer look at actions on a daily basis and evaluate if our own their behavior may be having a deleterious impact on others.

Refrain from posting or sharing uncivil material online. While this is intuitive and perhaps simplistic, half of all incivility is encountered in search engines and on social media. What may seem civil to the poster/sharer, may be considered very uncivil to others. Through sharing and liking, our content often gets seen by people who aren’t our direct social media contacts.

Allow the other person to speak and listen empathetically while he or she is speaking.Stephen Covey said “Seek first to understand, then to be understood.” This continues to be great advice decades after the publication ofThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.

Refrain from immediately blaming the other side or your opponent for everything that goes wrong.Assigning blame to someone else is a defense mechanism at times and on other occasions is used to denigrate others.

Even assigning blame puts people on the defensive and rarely leads to effective problem solving or progress. Author Steve Maraboli offered great insight on the blame game with this statement: “It’s time to care; it’s time to take responsibility; it’s time to lead; it’s time for a change; it’s time to be true to our greatest self; it’s time to stop blaming others.”

Recognize that people aren’t always morally bankrupt or mentally defective if they disagree with you. We are all subject to a number of influences and biases. Everyone has a tendency to define reality in accordance with their personal beliefs. Be objective and acknowledge other opinions.

Speak in measured tones and avoid shouting people down to win arguments. Such victories are short-lived and produce lingering resentment. Displays of anger rarely inspire confidence and well-reasoned counterpoints will likely foster greater support. In Leadership Jazz, author Max DePree wrote that “Leaders exemplify personal restraint in their behavior.” This statement applies to so much that public leaders do, including how they express themselves.

Avoid social media diatribes. Thoroughly consider the impact of your words before hitting send. Have a respected advisor review your statements if you have any doubts. The practice of engaging your brain first obviously applies to speech as well.

Quoted in Forbes magazine on July 8, 2013, social media authority Steve Olenski made this great suggestion: “Pause to put emotions in check. Never post a comment when you’re feeling emotionally triggered. Never! If you wait four hours you¹re likely to respond differently.”

Speak the truth and avoid lying or exaggerating to convince people.When in doubt about the facts, it is reasonable to say, I don’t know but, I will check into it. Benjamin Franklin once said, “Half the truth is a whole lie.” Although it is often tempting to manipulate the facts to our advantage, doing so ultimately compromises an individual’s integrity.

Seek the common ground.Most of the greatest triumphs of humanity were the result of collaboration and, yes, even compromise. In reference to interactions between couples, the Gottman Institute relates the following: “Remember, you can only be influential if you accept influence. Compromise never feels perfect. Everyone gains something and everyone loses something.”

Genuinely apologize when we are wrong. ditors at Oxford Dictionaries recently added an entry for “non-apology,” defining it as a statement that takes the form of an apology but doesn’t sufficiently acknowledge responsibility or regret. Oxford also added an entry for “apology tour,” a series of public appearances by a well-known figure to express regret over a wrongdoing.

“I want to apologize is not an apology.” It’s no more an apology than “I want to lose weight” is a loss of weight. “I’m sorry if you were offended,” or “I’m sorry I hurt your feelings” are not apologies. These imply that the inured party may be too sensitive, and the problem is their perception of what happened. “I’ve really been upset over what I did,” or “I’m losing sleep over this,” are not apologies.

They put the focus on the transgressor’s well being and ask the offended party to show compassion and caring for the transgressor. “Everybody makes mistakes, and I’m not perfect,” is not an apology. It avoids personal responsibility by projecting the responsibility onto others. “I hope you won’t hold this against me,” is not an apology. It’s passive aggressive at best and aggressive at the worst because it implies some retribution or punishment of the injured party. For example, someone says “I called you an idiot but I’ve been under a lot of stress/have too much going on.” This is not an apology but a rationalization or excuse. The give away is often the word “but.”

The non-apology often puts the blame on the critics of the perpetrator, because the message is “If anyone is stupid or too insensitive to be offended by what I did, then I guess I apologize, but only because their unreasonableness forces me to do so to make the problem go away.” This illustrates a lack of empathy, insincerity and a refusal to accept personal responsibility for their own acts. Language is also manipulated in a non-apology to give the appearance of an apology.

Hold elected officials politically accountable for incivility. Many citizens would assume that holding politicians accountable for their actions isn’t too difficult in a representative democracy that values civic engagement. Citizens have a right to hold their representatives accountable for the words and actions they take.

Hold the media accountable.Vote with your viewership and let advertisers know you will not support incivility.

When applying for jobs, look for civil trustworthy employers, perhaps those who contribute to civilization as well as their own profitability. Never put yourself in the position of working for an organization that is dishonest or abusive just for the sake of having a job.

Do not tolerate bad behavior, bullying, management by intimidation, or a generally abusive workplace, once hired. Report those who engage in abuse, and don’t tolerate any directed at you or others.

Incivility is an open door to the degradation of democracy and a civil society. The time to take action is now.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself and Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.