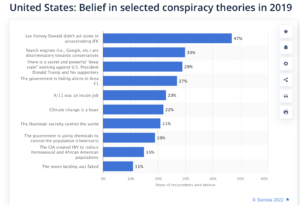

Particularly in American politics, conspiracy theories and the number of people who believe in them appear to be increasing daily. A 2019 poll from Insider found that nearly 80% of people in the United States follow at least one unproven theory, conspiracy or not.

The question is, Why do so many people believe in them? Why do even the most preposterous theories — the Nazis survived but they fled to the moon; the world is secretly being run by a reptilian elite — have fiercely loyal adherents? There are nearly as many explanations for conspiracy theories as there are theories themselves, but some patterns do appear again and again.

The most common theories are the ones that follow the eddies of politics. As a broad rule, a party or group that’s out of power will be more inclined to believe in conspiracies than a group that’s in power.

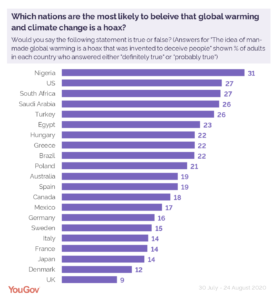

Conspiracy theories have been gaining traction since the coronavirus outbreak broke out, especially on social media. Opinion researchers from Germany’s Allensbach Institute polled 1,000 representative residents in each of the United States, Great Britain, France, and Germany in June 2020 to learn more about the diffusion and acceptance of such conspiracies. Up to 22% of Americans think that “there is more to them than the official explanations of the events” when it comes to purported conspiracy theories. Additionally, one in four Americans prefers to get their news from unbiased sources because they feel that the mainstream media “are not telling the truth about corona.”

For instance, a 2018 poll indicated that 60% of Britons held a conspiracy belief. The emergence of QAnon in America, meanwhile, has been extremely concerning.

Conspiracy theorists are simple to reject, but doing so is not the best course of action. Instead, scientists are trying to understand why people buy into such belief systems, even at the cost of interpersonal ties. This research can shed some light on how conspiracies spread and offer some helpful advice for approaching family members who might have bought into a conspiracy idea.

Why do People Believe in Conspiracies?

There are several reasons why someone might be drawn to a conspiracy theory, many of which are connected to unmet psychological needs.

The first of these wants, according to Karen M. Douglas, professor of social psychology at the University of Kent, “is epistemic, relating to the need to know the truth and have clarity and certainty.” The other wants include social, which are related to the desire to uphold our sense of self-worth and feel good about the organizations we are a part of, as well as existential, which are tied to the need to feel safe and to have some influence over the events taking place around us.

Thus, if someone is fearful of the pandemic and feels out of control, they can be lured to beliefs that contend it is untrue because they meet their existential demands. To satisfy their need for epistemic satisfaction in the face of a particularly frustrating political scenario, individuals may begin investigating seemingly simple answers to intractable problems.

There are a variety of other risk factors associated with conspiracy beliefs, such as political apathy and the desire to feel special, which can also be sources of conspiracy ideas. According to Stephan Lewandowsky, co-author of the Conspiracy Theory Handbook and Chair in Cognitive Psychology at the University of Bristol, those who are less critical thinkers are also more inclined to believe in conspiracies.

According to Lewandowsky, those who believe in conspiracies “often believe that intuition is a better method to know the truth than data — people who think their gut feeling is telling them what to believe and who don’t need or want proof to make a decision.” They lack a healthy dose of skepticism, Lewandowsky says.

One of the reasons conspiracy theories are so difficult to disprove is that they are “self-sealing” by nature, which means that evidence cannot be used to disprove them. Lewandowsky argues, “The absence of any proof is assumed to be evidence for the theory.” “As an illustration, somebody last year claimed on YouTube that Anthony Fauci was directly directing funding to a lab in Wuhan. he said, “See, that’s how good the cover-up is; when the interviewer stated that there was no evidence. Because they so effectively conceal it, there is no evidence.”

Adrian Furnham, a psychologist, examined the psychology and worldview of conspiracy theorists in two recent research studies, one in Current Psychology and the other in the International Journal of Social Psychiatry.

Most conspiracy theories believers also believe the world is unfair, and life is difficult.

“Conspiracy theorists are frequently illiterate and failing in their occupations. These people use conspiracy theories as a means of giving their struggles some sort of purpose, according to Furnham.

He explains in his research involving more than 400 participants that conspiracy theorists believe the world is unfair because they observe awful things occurring to nice people in a study. “This prompts some marginalized members of society to search for patterns in the injustice and pinpoint what they believe are hidden or covert causes for events. It is an illusion of power over an immovable object,” he says.

Personality Issues Frequently Contribute.

In his second study involving 500 participants, Furnham reports that conspiracy theorists may experience certain well-known personality disorders.

“They are usually strange or quirky individuals who are frequently self-centered. They think that rather than themselves, it is the world that is flawed or out of whack. In addition to having a general mistrust of society and authorities, they frequently exhibit social awkwardness and tend to isolate themselves,” according to Furnham.

Additionally, he says, they frequently have exaggerated emotions and dramatic thinking patterns. By accepting some truths while dismissing others, for instance.

According to a study by Joshua Hart and Molly Graether published in the journal Individual Differences, people who believe in conspiracy theories tend to show personality traits and characteristics such as:

- paranoid or suspicious thinking.

- low trust in others.

- stronger need to feel special.

- belief in the world as a dangerous place.

- seeing meaningful patterns where none exist.

According to the study, having a personality that falls into the “schizotypy” spectrum—a collection of personality traits that can range from magical thinking and dissociative states to disorganized thinking patterns and psychosis—is the biggest predictor of belief in conspiracy theories.

Research by A. Lantian and colleagues published in Social Psychology also suggests that belief in conspiracy theories is linked to people’s need for uniqueness. The higher the need to feel special and unique, the more likely a person is to believe a conspiracy theory.

Other personality traits commonly linked to the tendency to believe or follow conspiracy theories include narcissism, low agreeableness, Machiavellianism, and less openness to experience,

Professor of clinical psychiatry Richard A. Friedman, MD, writes in his viewpoint paper, “Why Humans Are Vulnerable to Conspiracy Theories”: “Having the capacity to imagine and anticipate that other people might form coalitions and conspire to harm one’s clan would confer a clear adaptive advantage: a suspicious stance toward others, even if mistaken, would be a safer strategy than carefree trust.”

In other words, from an evolutionary perspective, a conspiracy theory might help you stay safer if your rival attacks, as you have already anticipated their moves. “The paranoia that drives individuals to constantly scan the world for danger and suspect the worst of others probably once provided a similar survival edge,” Friedman adds.

Illusory patterns

Acceptance of conspiracy theories has been linked to processing problems in the brain.

Illusory pattern perception is the belief that unrelated events have meaningful or coherent links. In other words, you are more prone to perceive correlations between events that do not exist if your thinking is warped.

The political scientists Eric Oliver and Thomas Wood reveal some shocking results regarding how pervasive conspiracy theories are and what motivates people to believe them in their recently released study,“Conspiracy Theories and the Paranoid Style(s) of American Politics.”

In their investigation, they questioned participants in 8 nationally representative polls that were conducted starting in 2006 about 20 distinct conspiracy theories. In a few of their surveys, they tried to quantify the traits they thought would be correlated with conspiratorial thinking.

They found that each year, on average, about half of the population subscribes to at least one conspiracy theory. Some of the most popular theories include those that the FDA is purposefully withholding natural cancer treatments (supported by 40% of respondents), the “birther” conspiracy regarding Obama (supported by about 25% of respondents), the “truther” conspiracy regarding 9/11 (supported by about 19%), and the theory that the Federal Reserve purposefully stoked the 2008 recession (endorsed by 19 percent).

Contrary to popular opinion, conspiracy theorists are not always crazy or associated with conservatism, according to the authors. Those with less education do appear to be more likely to believe in conspiracies. It should not be surprising that conspiracy theorists experience more political alienation and worse levels of interpersonal trust.

Believers in the supernatural, the paranormal, or biblical prophecy are much more likely to be conspiracy theorists. However, if someone also holds other magical ideas is the biggest sign of whether they believe in conspiracy theories.

According to Joseph Uscinski, co-author of the 2014 book American Conspiracy Theories and associate professor of political science at the University of Miami, “conspiracy theories are for losers.” Uscinski emphasizes that he uses the phrase literally and not in a derogatory way.

“People look for something to justify that loss when they lose an election, money, or influence,” Uscinski says.

The most well-liked conspiracies practically shift as soon as a new president assumes office because of this tendency’s dependability and predictability, at least in the United States. The suspected murder of Vince Foster and claims that Clinton allies were trafficking cocaine in Arkansas were the two principal conspiracies that came to light while Bill Clinton was president. After George W. Bush was elected president, new conspiracies surfaced, this time claiming that Vice President Dick Cheney, Halliburton Energy, and the security company Blackwater planned the invasion of Iraq to seize control of the nation’s oil.

Not all disgruntled out-party participants believe in or participate in the prevailing conspiracies. Additionally, demographics are important because money and education are often adversely connected with the belief in the theories. A survey found that 23% of those with postgraduate degrees and 42% of people without a high school education believe in conspiracies. A 2017 survey found that the average household income for those who were inclined to believe in conspiracies was $47,193, compared to $63,824 for those who weren’t.

Political science professor at Notre Dame University and co-author Joseph Parent compare conspiracy theories to emotional poultices in this situation. “You choose to place the blame on unidentified forces rather than taking responsibility for what you may lack,” he says.

Sometimes the need to stand out or be different, which spans demographic lines, fuels conspiracy beliefs. Participants had the choice of taking a survey to determine their desire for individuality or writing an essay on the significance of free thought in a study with the provocative title “Too Special to Be Duped” that was published in May 2017 in the European Journal of Social Psychology. The inclination to believe in various conspiracies was significantly higher among those who scored highly on the need to stand out from the crowd or who were already inclined to feel that way by writing the essay. The need to stand out from the crowd, according to the researchers, “plays a modest role in increasing the adoption of…irrational views.”

This explains why conspiracy theorists rarely alter their beliefs despite evidence refuting their theories because doing so would require them to give up their uniqueness. The lengthier version was requested by the doubters after President Obama issued his short form birth certificate to allay questions about his place of birth. When he revealed that, they said it had to be a fake. According to Uscinski, “they just move the goalposts.”

Despite being complete nonsense, some conspiracy theories can be an attempt to make the world make more sense. After a significant national tragedy, such as the assassination of President Kennedy, something called the “proportionality bias” may develop where people become uncomfortable with the idea of minor causes having such significant effects. The fantasy of a CIA or Mafia plot has so replaced the reality of a lone gunman who succeeded to shoot the President. As more people join the group, the chance that any one of the believers will quit grows less likely. Group membership becomes important, claims Notre Dame professor Parent. “The beliefs are almost like gang tattoos.”

That indestructibility is the problem. Nobody is injured by talking continuously about the reptilian elite, other than maybe not getting asked to dinner parties. The fallacies about vaccines being dangerous will, however, make you less likely to immunize your children, which can be fatal.

QAnon: The Excitement of Living in “Fiction”

QAnon, a U.S. online conspiracy theory that includes well-known elected officials, has recently attracted the interest of a sizable portion of the general public.

The central tenet of QAnon is that during the tenure of former U.S. President Donald Trump, a cabal of Satanic, cannibalistic child sex abusers and traffickers worked against him. The internet conspiracy theory “Pizzagate,” which first surfaced a year earlier, has a direct influence on QAnon, and it also borrows ideas from numerous other theories.

Although QAnon isn’t the first conspiracy theory, it may be the most popular. QAnon encompasses the majority of other conspiracies you are aware of, like the phoney moon landing, 9/11, and the JFK assassination. That’s because “Q” asserts that everyone is playing along. You—the common citizen—are being taken advantage of by the government, the media, Hollywood, the education and healthcare industries, and perhaps even your grandmother.

The five core principles of QAnon are as follows:

- A bad cult controls the world (similar to the Illuminati).

- Donald Trump is a hero to Americans.

- Foreign, anti-American forces with evil motives run the Democratic party.

- QAnon members are united in their correct set of beliefs.

- The only real patriots are QAnon adherents.

This conspiracy theory holds that an unnamed government insider known only as “Q” frequently drops enigmatic hints and puzzles to reveal the “deep state” network.

The Danger in QAnon

It has been well-established that QAnon believers and followers were actively involved in the January 6 insurrection, and many were part of the domestic terrorist groups Oathkeepers and Proud Boys, which illustrates that QAnon supporters are prepared to take violent action.

How to Interact with Someone Who Believes Conspiracy Theories

In a perfect world, we would stop conspiracy ideas before they even start. Conspiracy theories can be “inoculated,” as Douglas and her colleague Daniel Jolley point out in their study on the anti-vaccination movement.

When provided before conspiracy beliefs, they discovered that the intention to vaccinate a child increased. Even with reasons that were factually sound and appeared reasonable, however, once these conspiracies were formed, they became extremely harder to disprove.

As a result, “prebunking,” as Lewandowsky and other authors call it, is the process of engaging someone before they become entrenched in the world of conspiracy theories. It’s important to encourage individuals to think critically and equip them with strategies to guard against false information, as David Robson noted in an article for The Psychologist. (The game “Bad News,” created by researchers at the University of Cambridge, is one instance of an intervention that emphasizes critical thinking.)

But it’s not simple to disprove a conspiracy idea after it’s become widespread. It’s challenging to convince someone to change their mind when they have such strong convictions, according to Douglas. People are particularly skilled at choosing and interpreting information that seems to support their existing views while rejecting or misinterpreting information that contradicts them.

However, according to scholar Jovan Byford in The Conversation, “conspiracies are based on feelings of hatred, outrage, and dissatisfaction about the world.” Therefore, it’s critical to comprehend and make an effort to understand the emotions that may be driving someone’s erroneous views.

Anxiety was linked to COVID-19 conspiracy theories, according to a study published in Personality and Individual Differences earlier this year. Another study indicated that many COVID-19 conspiracy theorists also felt powerless over their lives and the political positions they were in.

According to Douglas, those who believe in conspiracies could feel “confused, anxious, and isolated.” Therefore, behaving in a nasty or mocking manner toward them would be ineffective. According to her, “This ignores their viewpoints and can further alienate them and drive them into conspiracy theories.” It’s critical to remain composed and pay attention. Lewandowsky concurs, saying that empathy is the key to everything. “There is data to show that you shouldn’t do that. Insulting individuals doesn’t help.”

If you truly disagree with someone’s worldview, it can be difficult to avoid responding in a hostile manner, as anyone who has had a contentious family discussion over politics will attest. However, according to Harvard Business School research that was published in the journal Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, being receptive may be the better course of action.

The team, headed by Mike Yeomans, contends that “conversational receptiveness” is essential to de-escalating conflict: if you speak to someone in a way that conveys you’re open to their perspectives and beliefs, they’ll be more likely to be persuaded by yours.

Therefore, using simple words like “I get that” or “What you’re saying is” might help you communicate with people who have quite different opinions from your own. Even if this doesn’t mean they repudiate conspiracist beliefs, it can still help a relationship be cordial and non-hostile.

Power and Purpose

Lewandowsky notes that empowering individuals may also aid in thwarting conspiratorial thinking. As we’ve seen, having a sense of control can assist prevent conspiracist thinking because it’s well-known that believing in conspiracies is closely related to feeling helpless.

People can gain personal power through treatments that promote analytical thinking and serve as reminders of times when they were in charge. In one study, for instance, participants were asked to recollect a circumstance in which they were in control, and those who were asked to recall a situation in which they were out of control were less likely to believe in a conspiracy theory. These strategies could enable you to communicate effectively with a loved one.

Restoring people’s sense of control is one action that can be taken, according to Lewandowsky. “People who feel like they’ve lost control of their life and are terrified often turn to conspiracy theories,” says the author. “That’s one of the reasons why a pandemic will provoke more of this thinking because people have lost control of their lives.”

So that’s one deceptive approach: encourage someone to take command of their lives rather than trying to argue them out of it. They may eventually give up at that point because they are no longer in need of it.

This does not imply that it is always feasible to convince someone to change their mind. According to Lewandowsky, “the hard-core believers who are really down the rabbit hole… they are incredibly tough to approach.” When having conversations that could be difficult or upsetting, it’s equally critical to safeguarding your welfare. However, the first step to having a fruitful dialogue with someone who believes in conspiracy theories may be to treat them with understanding and composure.