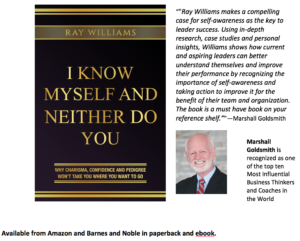

The following in an excerpt from my book, I Know Myself and Neither Do You, an examination of the importance of self-awareness for leaders.

“We do not serve the healthy development of young people when we convey that self-esteem may be achieved by reciting ‘I am special’ every day, or by stroking one’s own face while saying ‘I love me.’” — Nathaniel Branden, The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem

Accurate self-awareness and self-assessment become far more difficult if we have a distorted or exaggerated view of ourselves. Some experts blame the self-esteem movement of the last few decades for this development.

Self-esteem can be defined as an individual’s subjective evaluation of their own worth. Social psychologists and co-authors of Social Psychology (4th Edition), Eliot Smith and Diane Mackie have defined it: “The self-concept is what we think about the self; self-esteem, is the positive or negative evaluations of the self, as in how we feel about it.”

The American psychologist Albert Ellis criticized on numerous occasions the concept of self-esteem as essentially self-defeating and ultimately destructive. Although acknowledging the human propensity and tendency to ego rating as innate, he has critiqued the philosophy of self-esteem as unrealistic, illogical and destructive — often doing more harm than good.

These days, self-esteem has acquired a second meaning: “an unduly high opinion of oneself; vanity.” It is this definition that best fits Generation Y, according to Jean M. Twenge, professor of psychology at San Diego State University. She argues inflated egos leave many young people with unrealistic expectations, and their inability to achieve these can lead to depression. It is no coincidence, she says, that the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, reported that one in nine Americans over the age of 12 now takes antidepressants — a quadrupling of the rate since the late 1980s.

Twenge sees another sign of dangerously overblown self-esteem in rising levels of narcissism. She found that twice as many college students had high levels of narcissism in 2006 compared with the early 1980s. Narcissists tend to be intolerant of criticism and prone to cheating and aggression. “These are the people who wind up in your office arguing over a grade,” she says. In her book, The Narcissism Epidemic, written with co-author W. Keith Campbell, she recounts anecdotes of people hiring fake paparazzi to make themselves look famous, and buying “McMansions” on credit, as evidence of the Americans’ overblown ego.

“We have taken individualism too far,” says Twenge, and popular culture reflects this. She has worked with University of Kentucky social psychologist Nathan DeWall and others to chart an increase in the frequency of the word “I” in the lyrics of hit U.S. pop songs from 1980 to 2007.

Twenge blames four factors: Changes in parenting styles, the cult of celebrity, the internet and easy credit. “All of these things allow people to have an inflated sense of self in which the appearance of performance is more important than the actual performance,” she says.

Instagram is the most narcissistic social media platform on the planet, according to millennials.A survey of almost 10,000 students found the social media platform is more suited to the self-obsessed than Snapchat, Twitter and Facebook.

Most millennials know people who delete posts that don’t get enough likes.Tasha Eurich argues persuasively that we are “living in an age of focus on self and self- aggrandizement.” This corresponds to the rise of the age of self-esteem. Eurich goes on to say “an excessive self–focus obscures our vision of those around us and distorts our ability to see ourselves as we really are.” She quotes the research that shows an inverse relationship between how special we think we are and how self-aware we are.

Psychologist Roy Baumeister has studied the issue of self-esteem extensively. He reviewed 15,000 studies and found:

- The relationship between self-esteem and success was virtually nonexistent.

- People with high self-esteem are more violent and aggressive, and more likely to have relationship problems.

A new study published in the Journal of Personality, by Michael Kernis suggests that high self-esteem isn’t necessarily healthy self-esteem because there are different types of high self-esteem.

“There are many kinds of high self-esteem, and in this study we found that for those in which it is fragile and shallow it’s no better than having low self-esteem,” says researcher Kernis. “People with fragile high self-esteem compensate for their self-doubts by engaging in exaggerated tendencies to defend, protect and enhance their feelings of self-worth.”

Researchers say it was once thought that more self-esteem was necessarily better self-esteem. But in recent years, self-esteem has come under closer examination after discovering links to aggressive behavior.

For example, Kernis says high self-esteem can become harmful when it is accompanied by verbal defensiveness, such as lashing out at others when a person’s beliefs, statements, or values are threatened.

How Narcissism Negates Self-Awareness in Leaders

In its extreme form, exaggerated self-esteem in leaders can show up as narcissism. And narcissistic leaders in North America have been very successful from a financial perspective.

A research study completed by Charles A. O’Reilly III at Stanford’s business school surveyed employees in 32 large, publicly traded tech companies. He contends that bosses who exhibit narcissistic traits like dominance, self-confidence, a sense of entitlement, grandiosity and low empathy, tend to make more money than their less self-centered counterparts, even if the lower-paid CEOs exhibit plenty of confidence. O’Reilly says of the narcissists, “they don’t really care what other people think and depending on the nature of the narcissist, they are impulsive and manipulative.” O’Reilly goes on to argue the longer narcissistic leaders are at the helm, the higher their compensation in comparison with the rest of the leadership team, or in some cases the narcissistic bosses fire anyone who dares to question or challenge them.

There is a dark downside to this appearance of success, however, O’Reilly contends. Company morale often declines, and employees leave the company. And while the narcissistic or abusive leaders may bring in the bigger pay checks, O’Reilly says there is compelling evidence that they don’t perform any better than lower-paid, less narcissistic counterparts. This argument has been supported by Michael Maccoby in his book, The Productive Narcissist: The Promise and Peril of Visionary Leadership.

Maccoby points out that tech firms, particularly those in Silicon Valley, are where abusive leaders thrive. His article on the subject in the Harvard Business Review received an overwhelming response of affirmation. He says in business and sports it is assumed if you are a big winner, you can get away with being a jerk. Stanford University professor Robert Sutton argues such bosses and cultures drive good people out and claims bad bosses affect the bottom line through increased turnover, absenteeism, decreased commitment and performance. He says the time spent counselling or appeasing these people, consoling victimized employees, reorganizing departments or teams and arranging transfers produce significant hidden costs for the company. And he warns organizations that narcissistic behavior is contagious.

INSEAD business school Professors Gianpiero Petriglieri and Jennifer Petriglieri, authors of “Can Business Schools Humanize Leadership?” argue that we have experienced a “dehumanization of leadership” in which leadership is reduced from a cultural enterprise to a strict intellectual or commercial one, and in which leadership “distances aspiring leaders from their followers and institutions, resulting in a disconnect their inner and outer worlds.”

In my article “Why Do We Idolize the Narcissistic Boss, When We Know the Humble Ones Produce Better Results,” in The Financial Post, I argue “We all tend to be hypocritical about what makes a good leader — even management experts. We exalt and praise leaders who are nasty and abusive because they are financially successful; meanwhile, research shows that humble leaders whose focus is to serve others, are equally successful, and capture the hearts and loyalty of others.”

It’s my estimate that approximately 30% of the leaders I have coached over the past three decades had excessively high self-esteem and many of them displayed clear signs of narcissism. And in virtually all of these instances, the leaders lacked self-awareness.

So there may be limits to the value of high self-esteem, particularly when it comes to seeing yourself accurately.