By Ray Williams

August 5, 2020

The current virus pandemic, economic disruption and social distancing is understandably causing emotional turmoil for many people. As we do our best to deal with the accompanying stresses and anxieties, learning how to label our emotions when they occur can help us become grounded and calm.

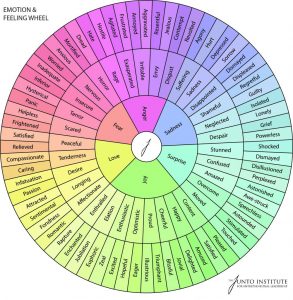

If I were to ask you “how are you feeling right now in this moment?” most people would pause and reflect or even have difficulty answering. If I then asked you which emotions have been strongest in the past few days, you might pause again, or come up with generic answers such as “okay,” “fine,” “not great,” which are not descriptions of emotions.

You are not alone if you had difficulty answering. Kim L. Gratz and Lizabeth Roemer, psychologists at the University of Massachusetts, published research showing that it is difficult to properly identify and label the myriad of emotions we experience on a regular basis.

Some people experience more difficulty labeling their emotions than others. Researchers Vera Vine and Amelia Aldao have shown, in their research people who have consistent difficulty also experience difficulties regulating their emotions.

An experiment on how labeling your emotion can help with emotional regulation

In a study by Michelle Craske at the University of California, Los Angeles the researchers recruited participants who had a spider phobiaand asked them to participate in a behavioral approach task (BAT). In this BAT, participants were told that they would have to take eight steps to get progressively closer to the feared spider. They could stop at any time. The researchers assigned each participant to one of four experimental conditions that differed in their instructions for what to do with the anxiety: 1) label the anxiety felt about the spider, 2) think differently of the spider so that it feels less threatening (reappraisal), 3) distract from the anxiety elicited by the spider, 4) no specific instruction (control condition). Participants then came back for a second BAT session so that the investigators could test the long-term effects of their emotion manipulation.

Interestingly, the investigators found that participants who had been assigned to labeling their emotions had lower physiological reactivity to the spiders, as indexed by fewer skin conductance responses. In addition, the authors found that within the affect labeling condition, participants who verbalized a larger number of fear and anxiety words had even fewer skin conductance responses! These findings suggest that having greater emotional clarity about one’s fear can help reduce the physiological manifestation of this emotion.

According to Matthew D. Lieberman, UCLA associate professor of psychology, seeing an angry face and simply calling it an angry face changes our brain responserecently published in the journal Emotion Review, . Lieberman refers to this as “affect labeling” and his fMRI brain scan research shows that this labeling of emotion appears to decrease activity in the brain’s emotional centers, including the amygdala. This dampening of the emotional brain allows its frontal lobe (reasoning and thinking center) to have greater sway over solving the problem du jour.

His study showed that while the amygdala was less active when an individual labeled the feeling, another region of the brain was more active: the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex which has been associated with thinking in words about emotional experiences. This area of the brain has also known for inhibiting behavior and processing emotions.

“What we’re suggesting is when you start thinking in words about your emotions –labeling emotions — that might be part of what the right ventrolateral region is responsible for,” Lieberman said.Lieberman explains it this way: “When you put feelings into words, you’re activating this prefrontal region and seeing a reduced response in the amygdala. In the same way you hit the brake when you’re driving when you see a yellow light — when you put feelings into words you seem to be hitting the brakes on your emotional responses. As a result, a person may feel less angry or less sad.”

Many people are not likely to realize why putting their feelings into words is helpful.

“If you ask people who are really sad why they are writing in a journal, they are not likely to say it’s because they think this is a way to make themselves feel better,” Lieberman said. “People don’t do this to intentionally overcome their negative feelings; it just seems to have that effect. Popular psychology says when you’re feeling down, just pick yourself up, but the world doesn’t work that way. If you know you’re trying to pick yourself up, it usually doesn’t work — self-deception is difficult. Because labeling your feelings doesn’t require you to want to feel better, it doesn’t have this problem.

Mindfulness and Labeling Emotions

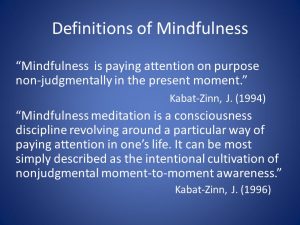

Mindfulness meditation, which originates in Buddhist practice, is now very popular in the west. Mindfulness meditation is an activity during which one pays attention to his or her present emotions, thoughts and body sensations, such as breathing, without passing judgment or reacting. Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn, one of the earliest researchers and promoters of mindfulness mediation describes the process as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.”

“One way to practice mindfulness meditation and pay attention to present-moment experiences is to label your emotions by saying, for example, ‘I’m feeling angry right now’ or ‘I’m feeling a lot of stress right now’ or ‘this is joy’ or whatever the emotion is,” said David Creswell, a research scientist with the Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA. He undertook a study to examine the effects of mindfulness meditation on the brain and emotions and published his results in Psychosomatic Medicine,a leading international medical journal for health psychology research.

Previous research has shown mindfulness meditation is effective in reducing a variety of chronic pain conditions, skin disease, stress-related health conditions and a variety of other ailments. Creswell and his UCLA colleagues concluded that when individuals label emotions, the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex was activated, which seems to turn down activity in the amygdala.

Cresswell and colleagues then compared participants’ responses on the mindfulness questionnaire with the results of the labeling study. “We found the more mindful you are, the more activation you have in the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the less activation you have in the amygdala,” Creswell said. “We also saw activation in widespread centers of the prefrontal cortex for people who are high in mindfulness and an increased capacity to turn down the amygdala.”

“We found the more mindful you are, the more activation you have in the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the less activation you have in the amygdala,” Creswell said. “We also saw activation in widespread centers of the prefrontal cortex for people who are high in mindfulness. This suggests people who are more mindful bring all sorts of prefrontal resources to turn down the amygdala. These findings may help explain the beneficial health effects of mindfulness meditation, he says, and suggest, for the first time, an underlying reason why mindfulness meditation programs improve mood and health.

Creswell says “Now, for the first time since those teachings, we have shown there is actually a neurological reason for doing mindfulness meditation. Our findings are consistent with what mindfulness meditation teachers have taught for thousands of years.”

In mindfulness noticing and labeling, the objective is to stand back, to observe our mental activity by using our attention to track our thoughts moment by moment, becoming interested in our thinking as well as feelings and sensations. We step back, we notice as an observer, without taking ownership of the content of our mind. Instead of being lost in thought, ruminating over past or future events, we wake up being present to what is here in the moment. We simply observe what is in our mind, noticing the wording of the thought(s), the intensity of the feeling(s), the location in our body of the sensation(s) without engaging with it.

When we turn our attention to our mind, we can begin to notice specific mental activity such as a specific thought, emotion or physical sensation saying something like: “I see you”, “Isn’t interesting that this is coming up!”, without judgment and then return to the present moment, coming into our body, to some point of focus which can be the sensation of breathing or the feet touching the ground. We can also increase the noticing by giving the thought, emotion or sensation a label.

Labeling can be done formally as a part of a meditation sitting practice or informally throughout the day. Labeling can also be done at the beginning of a meditation to settle the mind and subsequently in daily activities.

The aim here is to examine our habitual thought patterns, to take a step back, to get some perspective. In this way, we can break the cycle of rumination. It is simple and a great practice for the beginner as well as the advanced practitioner.

During a meditation, we choose a point of focus such as the awareness of the breath, or the footstep as in mindful walking and when our mind wanders, we kindly notice the “mental activity”, giving it a label and then coming back paying attention to being present with our chosen point of focus. We simply notice that the mind has wandered and that this was the content of the thought…with curiosity and kindness, without evaluating or analysing the thought.

We can use a general “action-verb” label, saying in our mind or aloud(if we are alone) “thinking” or specific label such as “planning”, “criticizing” or if we are distracted by a sound we can say “hearing” and then come back to whatever we had chosen to be an anchor for our attention. We can also name what we are observing using a general “noun” such “sensation” (tingling, aching, warm), “thought”( words, image, memory), “urge”( desire impulse) or “emotion” or “feeling” or “sound”. You can further increase the acceptance by saying something like “yes, I see you there”, “yes to whatever is here”.

It is also important not to spend too much time thinking about the kind of label you wish to use, remembering that the aim is simply to observe, to be aware, to be present. It is okay to use either vague or specific label, as long as you keep it simple and easy. You will become aware that the labeling is often after the fact or in hindsight. That is okay, that is just the nature of the mind. Also, you don’t have to label everything, just what you become aware of every so often. And it is okay to label the same thing over and over again if it is what is there for you. We encourage you to experiment with it and make it your own way.

We can also choose to specifically name the emotion such as “stress”, “anger”, “fear”, “joy”, “calm”. When we note and label, we can use a friendly and gentle tone which add a strengthening quality of compassion to our inner chatter. We can also choose to talk to our self in the third person. You can talk to yourself as a friend saying: “Tom you are feeling angry today” or observing yourself as a detached observer: “Tom is feeling angry today” or “Marie is thinking that she is not doing enough practice”.

As a friend, you can say: “Bev, you have a pain in your back” and further observer: “Bev is having a pain in the back”. Labeling as a friend in this way can give us a sense of being seen and understood. In addition, it creates a distance between what is happening and ourselves to reduce our reactivity. We don’t take it so personally. We don’t have to take ownership or authorship of it: “it is not your fault”, “you are not your fault”. This often helps to be more tolerating and accepting of our difficult feelings. We invite you to experiment, choosing whatever feels better for you.

Here’s a possible domino effect of reactive thoughts that might show up for you:

- Event occurs

- Your body stiffens, clenches

- You think, “I can’t believe this!” / “They are so wrong!” / “This shouldn’t be!”

- You feel, “I am angry / sad / frustrated / humiliated / etc.”

- Your body stiffens and clenches even more

- You decide, “I’m going to let them have it!”

And now, naming the emotion right AFTER the body first stiffens, surges, or in some way alerts you that upset is here:

- You think, “My body is telling me I’m angry, sad, etc.” (deep, slow breath in)

- You recognize, “I’m having thoughts that this is upsetting.” (slow exhale out)

- You feel, “Anger . . . anger . . . anger . . .” (deep, slow breath in)

- Your body slows down (slow exhale out)

- You feel, “Sad . . . sad . . . sad . . .” (deep, slow breath in)

You may notice a “distance” that develops as you label your thoughts and emotions after the initial event. Instead of reacting and either lashing out or shutting down, you (in a matter of seconds) can ignite your frontal lobe, slow your body and mind, and choose your response. You can connect with your experience, as well as the possibilities around you. Instead of digging a deeper hole, you can climb out of the episode.

The noticing and labeling practices assist in gaining clarity as to “what is” in the present moment. It helps us to gain some insight into our relationship with ourselves, with our experiences, with others and with our environment. Usually when we have “a thought”, we engage with it automatically, fusing with it. As we know, some thoughts can be very sticky, making it difficult to step back. With mindfulness, we practice gently pulling away from thoughts, again and again, pausing, observing, creating more and more space between the “mental event” and the response.

Another interesting finding was the difference between the immediate and longer-term effects of emotion labeling. This difference is important when considering how to practice this skill in our lives.

It turns out that, in the heat of the moment, when the emotion is activated, having a list of words accessible to choose from works best. But when left on your own, to figure out what you’re feeling, there’s likely to be a brief increase as you sift through your internal experience. The benefits of figuring out your own emotional state comes later, and lasts longer.

What this means is that there is a moment where the emotion has just been triggered and a choice to be made: Do I want to regulate it now (for the quick win) or regulate it over time, for the longer-term benefits?

So the first step in regulating your emotions is to stop trying to ignore your emotions – explicitly start building your emotion vocabulary and labeling your emotions.

The studies showed that the effects of emotion labeling can be attained by either speaking or writing about your feelings. Choosing from a list of words seemed to work best for regulating in the heat of a moment.

Each time, in the moment, when we are practicing noting and labeling, we are re-wiring the brain, because we are doing something different than what we would normally do. Each time we are noting and labeling, we are disengaging from the default mode network. Instead of automatically engaging with the thought, we are stepping out of thought, creating a space between our self and our thought, allowing for choosing and responding rather than reacting, becoming the wise observer of our mind. In this way, we are less at the mercy of our default mode which can get stuck in unhelpful rumination and preoccupation. When we become more aware, we wake up and free ourselves from our conditioning, we begin to live in a more conscious and intentional way.

The benefits of this technique are numerous. We stay with what is there for us, easing the resistance. It helps us to manage our emotions by breaking the experience into different manageable parts such as a thought, emotion and physical sensation. It promotes acceptance and reduces reactivity. We notice without immediate identification, making space, cultivating equanimity.

Research in neuroscience has shown that the labeling of thought helps to regulate emotion and promote insight during times of stress and emotional upset. Labeling with kindness is very beneficial as it slows the thinking mind, creating a space in our mind, where we can step back and observe. This has the effect also of calming the stress reaction in our body and not getting caught in the intensity of the emotion.

Research has shown that mental noticing and labeling help us to improve the emotional wiring in our brains. It produces a relaxing effect in our body, which helps us detach from thoughts. We stop identifying so personally with our thoughts and reacting emotionally to them. Rather than getting caught up in our thoughts, we train our minds to notice and label. Then we have more choice in terms of which thoughts we can intentionally pay attention to. By riding the rumination or emotion with our attention, through noting and labeling, we can free ourselves from excessive preoccupation or reactivity, becoming calmer, being more able to turn to the good things in our lives.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself and Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.