By Ray Williams, February 6, 2019

Leaders today must understand and apply the knowledge of neuroscience to manage organizational change successfully. In the past, efforts at organizational change which have focused on the structural aspects of organizations have systematically failed because they have neglected the reality that change doesn’t happen without individual people changing their thinking, beliefs and behaviour. In the past, efforts at organizational change focused on the structural aspects of organizations have systematically failed because they have neglected the reality that change doesn’t happen without individual people changing their thinking, beliefs and behavior.

What Is Neuroscience?

Neuroscience is a discipline that studies the development, the physical structures, and the chemical functions of the nervous system. One important question that neuroscience seeks to answer is how the human brain responds chemically to certain thoughts or events. Research has been made possible by advances in technology, including the development of functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI. Using fMRI, scientists can actually see which parts of a subject’s brain have been activated or deactivated.

Questions and Issues That Neuroscience Raises in Relation to Leadership and Organizations

- How does brain function affect leadership behavior?

- What are some conventional and traditional leadership practices and behaviors that are not supported by neuroscience research?

- How should neuroscience research evidence influence or change the recruitment, training and evaluation of leaders in organizations?

The Research

A challenge for the examination of neuroscience and leadership is how to technologically examine the topic. The technology associated with neurological assessment and research has advanced greatly in recent years. A number of techniques are now available to investigate brain activity that may be relevant to effective leadership behavior. For research purposes, two of the more popular ones are functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and quantitative electroencephalogram (qEEG). These techniques vary in terms of their precision and exact capabilities, but nevertheless represent a large improvement over past techniques in their ability to detect and quantify key aspects of brain activity. A key challenge for researchers is to attempt to make theoretical connections between brain activity and overt leadership behavior and qualities. Without such theory, research endeavors might simply involve searches for relationships between vaguely conceived neurological variables on the one hand and traditional, psychometrically based measures of leadership on the other.

Evian Gordon, a neuroscientist at the University of Sydney Medical School, outlines how the brain works in his book The Brain Revolution: Know and Train New Brain Habits. He calls it the 1-2-4 brain model:

- Our brain has a key organizing principle: minimize danger and pain and maximize reward. When our brain judges something to be threatening our perception of reality is affected because there are five times more neural networks for processing threats than rewards.

- Our brain has two operational modes: conscious and non-conscious. Most of our brain’s operations function at the level of the non-conscious.

- Our brain has four highly-integrated ways to process information: emotion, thinking, feeling, and self-regulation.

Research from Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky published in their book, Thinking, Fast and Slow identifies the brains quick or “hot” cognition involving instinct, quick reactions, and automatic responses, and the brain’s slow or “cool” system of careful reflection and analysis. Slow thinking can be seen as a sort of autopilot according to the authors. It’s helpful in certain situations involving obvious and straightforward decisions. But in more complicated decision-making contexts, it can cause more harm than good. Kahneman says Western business culture puts a premium on individualism and fast decision making, puttying a premium on quick action.

Various authors have proposed a specific neurological basis for emotional intelligence or skills. Daniel Goleman and his associates noted that emotional intelligence has a basis in brain circuitry and further suggested that it derives from cortical regions of the brain interpret and manage neurotransmitter signals from the brain’s limbic system. Morse (2006) suggested that a leader’s use of emotions and reasoning for the purpose of formulating and espousing a vision has a basis in the limbic system. Naqvi, Shiv, and Bechara (2006) further suggested that parts of the brain, such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, may help a person to balance emotions in decision making, especially in situations in which outcomes are ambiguous or uncertain. There is also recent research showing that regions of the cortex may help to assess risk and guide behaviors in anticipation of emotional consequences, including such negative consequences as fear and despair.

John Medina, a molecular biologist, author of Brain Rules: 12 Principles For Surviving and Thriving at Work, Home and School, argues “the brain is so sensitive to external experiences that you can literally rewire it through exposure to environmental influences.” For example, he says, we know that stress hurts the brain and that has a huge impact on productivity

Medina says there is no such thing as a perfect memory because the brain’s prime purpose is survival. So it will change the perception of reality to survive. The brain is not a perfect recording device.Medina also argues that long-term memory doesn’t happen instantly, but occurs over a long period of time.

David Rock and Jeffrey Schwartz, in their article for Strategy+ Business that ” the traditional command-and-control style of management doesn’t lead to permanent changes in behavior. Ordering people to change and them telling them how to do it fires the prefrontal cortex’s hair trigger connection to the amygdala. The more you try to convince people that you’re right and they’re wrong, the more they push back. The brain will try to defend itself from threats. Our brains are so complex that it is rare for us to be able to see any situation in exactly the same way as someone else. The way to get past the prefrontal cortex’s defenses is to help people come to their own resolution regarding the concepts causing through their prefrontal cortex to bristle.” Rock and Jeffrey Schwartz argue that by emphasizing mindful, focused attention on new management practices, rather than fixing old habits that don’t work, leaders can actually rewire their brains. McKinsey and Company is now incorporating their ideas into client workshops.

Dr. Robert Cooper, of Stanford Business School writing in Strategy and Leadership Journal, points out that “we actually have three brains–the one in our head, the one in our gut and the one in our heart, all of which have massive number of neurons. He claims that the highest reasoning involves all three brains working together. Traditional change in management tactics in organizations are based more on animal training than on human psychology and neuroscience.”

Cooper also says “Up to 96 percent of success in life and work depends on the brains in the gut and heart, not just the head.” We now know that intelligence is distributed throughout the body, Cooper contends. The brain in the gut is independent of, but also interconnected with the brain in the cranium. Scientists who study the elaborate systems of nerve cells and neurochemicals found in the intestinal tract now tell us that there are more neurons in the intestinal tract than in the entire spinal column–100 million of them. That complex circuitry enables this system to act independently, learn, remember, and influence our perceptions and behaviors. Whether or not you acknowledge your “gut reactions,” they are shaping everything you do, just as they shape everything that everyone around you does, all the time.

Cooper also says there is a brain in the heart. After each experience has been digested by the enteric nervous system, it’s the heart’s turn to ponder it. In the 1990s, scientists in the emerging field of neurocardiology discovered the true brain in the heart, which acts independently of the head. Comprising a distinctive set of more than 40,000 nerve cells called baroreceptors, along with a complex network of neurotransmitters, proteins, and support cells, this heart brain is as large as many key areas of the brain in your head. It has powerful, highly sophisticated, computational abilities.

The Center for Creative Leadership recently concluded that the only statistically significant factor differentiating the very best leaders from the mediocre ones is caring. It turns out that the oft-heard call to “keep emotions out of it” can result in bad decision-making.

A new field of leadership development is emerging, known as mBIT (multiple brain integration techniques) and it provides organizational leaders with practical methods for aligning and integrating their head, heart and gut brains for increased levels of emergent wisdom in their decision-making, and for developing an expanded core identity as an authentic leader.

Charles Jacobs, author of Management Rewired: Why Feedback Doesn’t Work and Other Supervisory Lessons From The Latest Brain Science, says the brain is wired to resist what is commonly termed constructive feedback, but is usually negative. When people encounter information that is in conflict with their self-image their tendency is to change the information, rather than changing themselves. So when mangers give critical feedback to employees, the employees’ brain defense mechanism is activated because that information conflicts with what the brain remembers and knows.

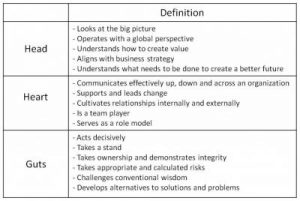

Jacobs’ views are supported by management guru Aubrey C. Daniels, writing in his book, Oops! 13 Management Practices That Waste Time and Money. He cites a study by the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) which found that 90% of performance appraisals are both painful and don’t work and further, and produce an extremely low percentage of top performers.In their popular leadership book, Head, Heart & Guts – How the World’s Best Companies Develop Complete Leaders,leadership experts David Dotlich, Peter Cairo and Stephen Rhinesmith make the case that leaders who operate only from the head are what they consider ‘incomplete leaders’. To truly thrive and lead successfully in today’s complex social and business environments, ‘whole leaders’ must learn to tap into the innate intelligence of their head, heart and guts.

Daniel Goleman and Richard Boyatzis conducted and published research on social intelligence and the biology of leadership. They argue that certain things leaders do—specifically, exhibit empathy and become attuned to others’ moods—literally affect both their own brain chemistry and that of their followers. Indeed, researchers have found that the leader-follower dynamic is not a case of two (or more) independent brains reacting consciously or unconsciously to each other. Rather, the individual minds become, in a sense, fused into a single system.

They argue great leaders are those whose behavior powerfully leverages the system of brain interconnectedness. Leading effectively is less about mastering situations—or even mastering social skill sets—than about developing a genuine interest in and talent for fostering positive feelings in the people whose cooperation and support you need. The notion that effective leadership is about having powerful social circuits in the brain has prompted us to extend our concept of emotional intelligence, which we had grounded in theories of individual psychology. A more relationship-based construct for assessing leadership is social intelligence, which we define as a set of interpersonal competencies built on specific neural circuits (and related endocrine systems) that inspire others to be effective.

A study by Christina Boedker from the Australian School of Business of more than 5600 people across 77 organizations, found that the single greatest influence on profitability and productivity was the ability of a leader to be compassionate. As Boedker observed, “It’s about valuing people and being receptive and responsive”, and finding ways “to create the right support mechanisms to allow people to be as good as they can be.” It’s important to note that compassion is not about pity, sympathy or niceness. It’s about deeply supporting and nurturing people to be the best they can be; to guide and coach them to bring the most calmness, creativity and courage to solving their issues and to flourishing within their organizational environment. As Geoff Aigner, director of Social Leadership Australia maintains in his thought-provoking book, Leadership Beyond Good Intentions: What It Takes To Really Make a Difference, good management is ultimately an act of compassion, and requires leaders to take responsibility for the growth and development of others.

Neuroscientist David Rock developed the SCARF Model.The SCARF model targets the top five social rewards and threats identified so far that are deeply important to the brain and these have relevance to leadership behaviors:

- Status

- Certainty

- Autonomy

- Relatedness

- Fairness

Status relates to a person’s relative importance to others. Certainty is about being able to predict the future. Autonomy provides a sense of control over events. Relatedness is the sense of connection and safety with others (the brain perceives a friend versus a foe). Fairness is the perception of being treated justly. These domains in the brain activate either a “primary reward” or “primary threat” response in the brain. For example, a perceived threat to one’s status will trigger a primary threat response in the brain because, as discussed earlier, the brain’s primary goal is survival. A perceived increase in fairness (an open discussion of a company’s compensation practices to assure all employees perceive that their compensation is fair and equitable, for example) will activate the same “primary reward” response as when receiving a monetary reward.

Fairness is core not only to humans but hard wired in primates as well. Primatologist Frans de Waal found that capuchin monkeys can discern unfairness, particularly when it comes to pay inequity. As he explains in a YouTube clip, when one capuchin monkey is rewarded with a cucumber for a completed task, she accepts it willingly—the first time. When she sees another capuchin monkey rewarded with a more desired grape for the same completed task and she is rewarded again with the less-desired cucumber, she throws the cucumber at the researcher.

Rock identifies status as one of the most significant drivers in the brain. A person will avoid a decrease in status in much the same way he or she would avoid pain, because the perceived threat of diminished status triggers the same area in the brain as pain. This is an important consideration, as previously discussed, when presenting change because change to the brain means a threat to social status.

The brain also craves certainty and predictability. When presented with any change, the brain will activate the limbic system and put it on alert, putting the recipient of the potential change into the “fight or flight” mode to survive. The brain also prefers autonomy, the ability to predict and have input into the future, so when presenting issues that may trigger uncertainty, HR and talent managers should consider how to calm those triggers by allowing employee discussion and participation into resolving the issues.

The brain also seeks connection with others—this is relatedness. Employees will respond better to bosses and peers whom they find to be “resonant.” Dissonant managers trigger a negative response in the brain, which then categorizes them as a foe, leading to distrust and disconnection. As mentioned, the brain is also a big proponent of fairness. A study conducted by Jamil Zaki of Stanford University and Jason Mitchell of Harvard University found that when people were allowed to divide up small amounts of money among themselves, the brain’s reward network responded much more when the participants made generous, equitable choices.

This model can be used as a guide to assess existing and proposed management practices and whether they trigger a “primary reward” or “primary threat” response in the brain.

The Implications for Leaders and Leadership Development

Given the rich data on neuroscience and the related fields of emotional and social intelligence, what do they provide as guidance for current and aspiring leaders, the structures for recruitment, selection and training of leaders?

- Educate leaders about the link between the brain and the importance of building positive relationships with employees. Neuroscience shows us that resonant leaders open pathways in their employees’ brains that can encourage engagement and positive working relationships.

- Pay attention to trust levels among managers and employees. HR and talent managers can emphasize trust development in leadership development activities, and highlight the neuroscience behind why trust is so important.

- Encourage leaders to use all three of their brains—the brain, the gut and the heart—in making decisions, and knowing the right sequence in specific situations.

- Understand that when a brain is put into a state of threat, our ability to think and perform is compromised. Leaders consequently want to create consistency and certainty for themselves and those around them. This will enhance a sense of security and predictability.

- Enable others’ autonomy. Exerting too much control or micromanagement can push others’ brains into a perceived threat mode which in turn makes them reactive, and subsequently their cognitive functioning declines.

- Create a just and equitable environment. Our brain also finds fairness highly rewarding. A sense of fairness begins in childhood and develops as we become adults. If employees believe they have been treated unfairly, their reaction can create more problems for managers

- Be masters of introspection and reflection.Leaders must be aware of their biases and blind spots and take appropriate action based on that reflection.

- Lead with greater empathy and compassion. Research on emotional intelligence points to empathy and compassion as both states of mind as well as behavioral competencies. And they can be enhanced and developed even if they are not initially a strong suite for leaders

- Understand that change can cause physical pain in the brains of people. When leaders introduce significant (and even sometimes less significant) changes in the organization that affect people, that can cause pain. So leaders should not deceive themselves into thinking even positive changes, let alone the negative ones, will be welcomed by all, and therefore, leaders should consider ways in which the pain can be lessened.

- Learn how to positively regulate emotions.This means, among other things, accepting that emotions are a legitimate and necessary part of leadership behavior; acquiring greater insight and sensitivity to one’s own and others’ emotions; and positively regulating one’s emotional responses (rather than being reactive, or repressing emotions). In this regard, mindfulness practices can be a tremendous help.

- Review and revise as necessary current organizational structures, processes and HR practices that are not supported by neuroscience research. It’s one thing to be acquainted with the research as an interesting exercise in reading, and quite another in intimating changes in leaders and organizations based on substantial scientific evidence.

Summary: The evidence from neuroscience (and related research) is substantial and significant, as it relates to the need to have great leaders and organizations where employees thrive. Doing things the way they’ve always been done is sure recipe for failure, one that we can’t afford today.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.