By Ray Williams

February 3, 2020

How often have you been in a situation when someone else triggers you into an immediate emotional reaction, leaving you feeling out of control or regretful after? Many people at one time or another can remember such a time. You may even replay the event in your mind repeatedly, hoping to see yourself in a calm, thoughtful state, where you intentionally responded.

What accounts for the difference?

Reacting is fast, instinctual and automatic behavior, where your primitive brain takes over. In his book, Just One Thing: Developing a Buddha Brain, One Single Practice at a Time, neuroscientist Rick Hanson explains the difference between the responding brain and the reactive brain. He describes the reactive brain (amygdala and brain stem) as reptilian, which emphasizes avoiding harm and protecting you. The responding or mammalian brain (prefrontal cortex) focuses on rewards and rationality.

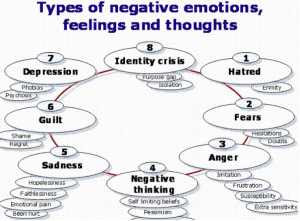

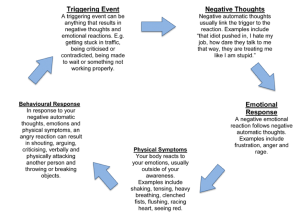

When anything happens to you to cause you to feel even the slightest bit threatened, whether it’s as simple as someone cutting you off in traffic, or a co-worker or boss being rude or abusive, your reptilian brain activates in a fight flight or freeze mode. These reactions were survival mechanisms in our distant past, but still happen in our modern world. Whenever you feel under stress, worried, irritated, frustrated, the primitive brain activates and if this is repeated often enough, it can lead to mental and physical health issues.

In a reactive mode your brain most strongly expresses fear and anger. In contrast, when you feel safe and not threatened, your brain’s reactive system is calm, soothed. Unfortunately, many people spend much of their time in the reactive mode. Remember, reacting is automatic and instinctual. Responding is a conscious and learned choice.

To be in a responsive state most of the time, you need to noticing how your body is reacting first and resist the urge to do something quickly. Rather, pausing and allowing your higher rational brain function to “catch up” is necessary.

There are several keys to being able to consistently respond rather than react. First, and perhaps more than importantly, pause before any action is taken. Second, identify and label the emotion you are feeling without judgment or anxiety to get rid of it. Next, reflecting on your inner state and what choices now lie in front of you. And last, make a choice and decision about how to respond.

How long should you pause? It depends on the severity of the need to react. Sometimes 10-20 minutes is sufficient, or longer if you need to reflect more.

Every time you pause and respond instead of automatically reacting, you are developing a good habit. Rick Hanson describes it in this way: “Each time you rest in your brain’s responsive mode, it gets easier to come to it again. That’s because neurons that fire together, wire together.

A fundamental aspect of reactivity is emotional regulation, which is the ability to respond to the demands of experience with a range of emotions in a flexible way, as well as an ability to delay spontaneous reactions. This in turn can also regulate others’ feelings in response. In addition, learning to respond rather than react is discovering what your emotional triggers, so that you immediately recognize them when they are set off. For example, you may get angry when someone is late for a meeting, or cuts in front of you in a lineup.

A key question arises: Now that you have identified and labeled your feelings when you are triggered to react, what do you do with them? The answer is nothing. Just being able to sit with them in a non-judgmental way, understanding that they are not permanent but will pass, is critical.

The Importance of Mindfully Labeling Your Feelings and Emotions

Why is putting our feelings into words beneficial? A brain imaging study by UCLA psychologists which appears in the journal Psychological Science, may give us the answer. Verbalizing our negative feelings makes excessive or persistent sadness, anger and pain less intense. In another study by these researchers they provided neural evidence for why “mindfulness” – defined as the ability to live in the present moment, without distraction – provides positive benefits as well.

According to one of the researchers, Matthew D. Lieberman, seeing an angry face and simply calling it an angry face changes our brain response. “When you attach the word ‘angry,’ you see a decreased response in the amygdala,” said Lieberman. His study showed that while the amygdala was less active when an individual labeled the feeling, another region of the brain was more active: the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex which has been associated with thinking in words about emotional experiences. This area of the brain is also known for inhibiting behavior and processing emotions. “What we’re suggesting is when you start thinking in words about your emotions –labeling emotions — that might be part of what the right ventrolateral region is responsible for,” Lieberman said.

In mindfulness noticing and labeling, the objective is to stand back, to observe our mental activity by using our attention to track our thoughts moment by moment, becoming interested in our thinking as well as feelings and sensations. We step back, we notice as an observer, without taking ownership of the content of our mind. Instead of being lost in thought, ruminating over past or future events, we wake up being present to what is here in the moment. We simply observe what is in our mind, noticing the wording of the thought(s), the intensity of the feeling(s), the location in our body of the sensation(s) without engaging with them.

When we turn our attention to our mind, we can begin to notice specific mental activity such as a specific thought, emotion or physical sensation saying something like: “I see you”, “Isn’t it interesting that this is coming up!”, without judgment and then return to the present moment, coming into our body, to some point of focus which can be the sensation of breathing or the feet touching the ground. We can also increase the noticing by giving the thought, emotion or sensation a label.

Labeling can be done formally as a part of a meditation sitting practice or informally throughout the day. Labeling can also be done at the beginning of a meditation to settle the mind and subsequently in any daily activity.

The aim here is to examine our habitual thought patterns, to take a step back, to get some perspective. In this way, we can break the cycle of rumination. It is simple and a great practice for the beginner as well as the advanced practitioner.

During a meditation, we choose a point of focus such as the awareness of the breath, or the footstep as in mindful walking and when our mind wanders, we kindly notice the “mental activity”, giving it a label and then coming back paying attention to being present with our chosen point of focus. We simply notice that the mind has wandered and that this was the content of the thought…with curiosity and kindness, without evaluating or analyzing the thought. We can use a general “action-verb” label, saying in our mind or aloud (if we are alone) “thinking” or specific label such as “planning”, “criticizing” or if we are distracted by a sound we can say “hearing” and then come back to whatever we had chosen to be an anchor for our attention. We can also name what we are observing using a general “noun” such “sensation” (tingling, aching, warm), “thought”( words, image, memory), “urge”( desire impulse) or “emotion” or “feeling” or “sound”. You can further increase the acceptance by saying something like “yes, I see you there”, “yes to whatever is here”.

It is also important not to spend too much time thinking about the kind of label you wish to use, remembering that the aim is simply to observe, to be aware, to be present. It is okay to use either vague or specific label, as long as you keep it simple and easy. You will become aware that the labeling is often after the fact or in hindsight. That is okay, that is just the nature of the mind. Also, you don’t have to label everything, just what you become aware of every so often. And it is okay to label the same thing over and over again if it is what is there for you. We encourage you to experiment with it and make it your own way.

We can also choose to specifically name the emotion such as “stress”, “anger”, “fear”, “joy”, “calm”. When we note and label, we can use a friendly and gentle tone which add a strengthening quality of compassion to our inner chatter. We can also choose to talk to ourself in the third person. You can talk to yourself as a friend saying: “Tom you are feeling angry today” or observing yourself as a detached observer: “Tom is feeling angry today” or “Marie is thinking that she is not doing enough practice”. As a friend, you can say: “Bev, you have a pain in your back” and further observer: “Bev is having a pain in the back”. Labeling as a friend in this way can give us a sense of being seen and understood. In addition, it creates a distance between what is happening and ourselves to reduce our reactivity. We don’t take it so personally. We don’t have to take ownership or authorship of it: “It is not your fault.” This often helps us to be more tolerating and accepting of our difficult feelings. We invite you to experiment, choosing whatever feels better for you.

The noticing and labeling practices assist in gaining clarity as to “what is” in the present moment. It helps us to gain some insight into our relationship with ourselves, with our experiences, with others and with our environment. Usually when we have “a thought”, we engage with it automatically, fusing with it. As we know, some thoughts can be very sticky, making it difficult to step back. With mindfulness, we practice gently pulling away from thoughts, again and again, pausing, observing, creating more and more space between the “mental event” and the response.

Each time, in the moment, when we are practicing noting and labeling, we are re-wiring the brain, because we are doing something different than what we would normally do. Each time we are noting and labeling, we are disengaging from the default mode network. Instead of automatically engaging with the thought, we are stepping out of thought, creating a space between ourself and our thought, allowing for choosing and responding rather than reacting, becoming the wise observer of our mind. In this way, we are less at the mercy of our default mode which can get stuck in unhelpful rumination and preoccupation. When we become more aware, we wake up and free ourselves from our conditioning, we begin to live in a more conscious and intentional way.

The benefits of this technique are numerous. We stay with what is there for us, easing the resistance. It helps us to manage our emotions by breaking the experience into different manageable parts such as a thought, emotion and physical sensation. It promotes acceptance and reduces reactivity. We notice without immediate identification, making space, cultivating equanimity.

Research in neuroscience has shown that the labeling of thought helps to regulate emotion and promote insight during times of stress and emotional upset. Labeling with kindness is very beneficial as it slows the thinking mind, creating a space in our mind, where we can step back and observe. This has the effect also of calming the stress reaction in our body and not getting caught in the intensity of the emotion.

Research has shown that mental noticing and labeling help us to improve the emotional wiring in our brains. It produces a relaxing effect in our body, which helps us detach from thoughts. We stop identifying so personally with our thoughts and reacting emotionally to them. Rather than getting caught up in our thoughts, we train our minds to notice and label. Then we have more choice in terms of which thoughts we can intentionally pay attention to. By riding the rumination or emotion with our attention, through noting and labeling, we can free ourselves from excessive preoccupation or reactivity, becoming calmer, being more able to turn to the good things in our lives.

A Habit System for Responding Rather Than Reacting

You can develop a good habit system for responding rather than reacting, so that it becomes automatic for you. Here are some of the elements of that habit system.

- Be aware and alert to your triggers. Recognize the events and people who can behave in ways that trigger you to be reactive.

- Focus on your breathing.By focusing on breathing evenly you can bring it under control. When we are triggered and in an immediate reactive state, our breathing often changes to become shallow, or we may even hold our breath. This can reduce the amount of oxygen going to our brains which in turn can negatively impact our rational abilities.

- Be awareness of your body.With each breath we can become more aware of our body. We can increase our attention by noticing if any part of your body has tension or pain, and focus on that.

- Release tension.If there is tension in your body, you can breathe into releasing it, so you don’t carry it or develop muscle or nerve issues.

- Increase focus and attentiveness. As you develop and maintain your calmness and non-reactivity, you can increase your capacity to notice and observe, which subsequently enables you to respond more thoughtfully.

- Label your feelings.Being able to identify and describe in words your feelings increases your ability to regulate your emotions and strengthens the value of the pause.

- Suspend judgment.This comes in two forms. First, suspend any self-judgment about the feelings or emotions that arise reactively. Rather, just notice them without criticizing yourself for having them. They are what they are.

- Practice acceptance.When feelings and emotions arise within you, accept them for what they are. Trying to block them or repress them will only make them stronger.

- Be more curious.Reflect on how and why you react to triggers.

- Try not to personalize things.Events and others’ behaviors are not always about you. Many times they have nothing to do with you but the causes lay elsewhere.

- Be an active and empathetic listener. If you are triggered to react, try to listen more and feel what the other person may be feeling.

- Practice compassion for others and yourself.Refrain from being self-critical and self-judgmental about your impulse to be reactive. No one or nothing can be perfect.

- Be the change you want to see in others.Ask yourself if you are modelling and demonstrating the behaviors you expect of other people.

- Intentionally respond.Choose what is the best response to a situation or person, once having taken the steps and actions described above.

Learning how to intentionally respond to people and events rather than instinctively react to them will give you a greater feeling of self-control and increase your self-mastery.

- I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.

- Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble world-wide..