By Ray Williams

June 11, 2020

In 1967, Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote, “I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective – the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.”

The economic destruction brought on by the COVID-19 global pandemic has brought up many comparisons to the Great Recession of 2008-09. While that crisis started in the financial sector and bled through the entire economy, this one was brought on by a global health crisis that caused the worldwide economy to come to a sudden stop, dislocating supply chains, industries, enterprises, small businesses, and consumers in unprecedented ways.

The government and central bank response to this crisis, like that of 2008-09, has also been swift and unprecedented. But there are already signs that the relief and policy measures will be handed out unevenly, as they were in the last crisis, creating even more income inequality in America.

Nobel laureate, professor and best-selling author Joseph Stiglitz was among leading economists decrying the rise in income inequality and the bailout of Wall Street in 2008 as Main Street slogged its way through years of a slow recovery. Just before the onset of the global pandemic, Stiglitz authored his latest book, People, Power, and Profits, which chronicles how the masses have lost economic leverage and lays out a path for a more progressive capitalism that shrinks income inequality.

Stiglitz says “ One of the marked aspects of American inequality is that health inequalities are even greater than our income and wealth inequalities. COVID-19 has brought out the magnitude of these inequalities. Republicans have taken the view in Congress that the states should be on their own, and the states are responsible for education, for health, for social welfare. The states all have balanced budget frameworks. They can’t borrow.The states don’t have the facility to print money like the federal government does. The states are about to be hit by a revenue shock that is surely greater than in 2008. That means if there is no assistance from the federal government, there will be significant cutbacks in education and health and so forth, and the inequalities that we’ll see in our society will be all the greater.”

Stiglitz argues “we learned that markets often don’t work well. The markets weren’t able to supply us with masks. They don’t respond in emergencies in the relevant timeframe. Of course, even before the crisis, dramatically in the 2008 crisis, we had seen that they were shortsighted. But this crisis has reinforced the point: We have created an economic system that is not resilient, and can leave us unprepared.”

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed some uncomfortable truths about the state of America today. First and foremost is the fragility of the American economy. After years of outsourcing manufacturing, the United States has constructed an economy where services industries comprise some 55 percent of overall economic activity. In the age of globalization, with interconnectivity functioning seamlessly, this model has been able to generate the appearance of prosperity, with a booming stock market and increased GDP.

American corporations have been shown to have little capacity to plan for “rainy day” contingencies, instead focusing all their economic resources on the generation of short-term profit. And the American working class has been likewise exposed as living on the edge of catastrophe, with few Americans able to fall back on savings that would enable them to ride out a period of sustained economic inactivity or, worse, to pay for emergency health care.

The other uncomfortable truth about America that has been exposed by the crisis is the overall fragility of American society. The medical emergency brought about by the need to treat this virus has shown that what passes for a national healthcare system is, in fact, a fragile construct of for-profit institutions susceptible to being rapidly overburdened and unable to function once the cash-stream of overpriced healthcare has been cut off. The coronavirus crisis has revealed the reality of the US healthcare system today – most Americans don’t have the wherewithal to get quality healthcare when needed – the cost of such care is prohibitive, as are the insurance premiums one must pay to cover it.

Economist Mariana Mazzucato, Professor of Economics of Innovation and Public Value, Founder and Director, Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, University College London, says the COVID-19 pandemic will shine light onto societal and economic systems all across the world, exposing some of the flaws of a capitalist society.

She contends Capitalism is facing at least three major crises. A pandemic-induced health crisis has rapidly ignited an economic crisis with yet unknown consequences for financial stability, and all of this is playing out against the backdrop of a climate crisis that cannot be addressed by “business as usual.” Until just two months ago, the news media were full of frightening images of overwhelmed firefighters, not overwhelmed health-care providers.

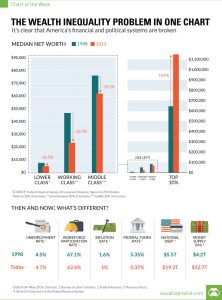

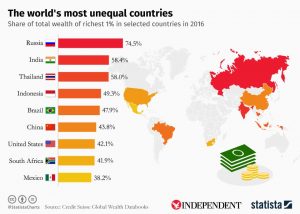

Inequality in America

On December 17,2017, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, issued a damning report on his visit to the United States. He cited data from the Stanford Center on Inequality and Poverty, which reports that “in terms of labor markets, poverty, safety net, wealth inequality, and economic mobility, the US comes in last of the top 10 most well-off countries, and 18th amongst the top 21.” Alston wrote that “the American Dream is rapidly becoming the American Illusion, as the US now has the lowest rate of social mobility of any of the rich countries.” Just a few days before, on December 11, The Boston Globe’s Spotlight team ran a story showing that the median net worth of nonimmigrant African American households in the Boston area is $18.00

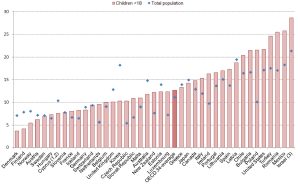

The Stanford report stated: “Over the last 30 years, wage inequality in the United States has increased substantially, with the overall level of inequality now approaching the extreme level that prevailed prior to the Great Depression.” In addition, “In the United States, 21 percent of all children are in poverty, a poverty rate higher than what prevails in virtually all other rich nations.”

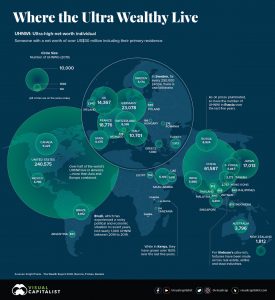

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, OECD and numerous other studies economic inequality is increasing in America, not getting better. In 2018, the top 20% of the population earned 52% of all U.S. income. Their average household income was $233,895. The richest of the rich, the top 5%, earned 23% of all income. Their average household income was $416,520.

The bottom 20% only earned 3.1% of the nation’s income. The lower earner’s average household income was $13,775. Most low-wage workers receive no health insurance, sick days, or pension plans from their employers. They can’t get ill and have no hope of retiring. That creates health care inequality, which increases the cost of medical care for everyone. Also, people who can’t afford preventive care will wind up in the hospital emergency room. In 2009, half of the people (46.3%) who used a hospital said they went because they had no other place to go.

Approximately 30% of American workers make less than $10.10 per hour. That creates an income below the federal poverty level. These are the people who wait on you every day. They include cashiers, fast food workers, and nurse’s aides.

The rich got richer through the recovery from the 2008 financial crisis. Between 1993 and 2015, the average family income grew by 25.7%. The top 1% of the population received 52% of that growth.

This worsening of income inequality had been ongoing even before the recession. Between 1979 and 2007, household income increased 275% for the wealthiest 1% of households. It rose 65% for the top fifth. The bottom fifth only increased by 18%.

That’s true even after “wealth redistribution,” which entails subtracting all taxes and adding all income from Social Security, welfare, and other payments.

Since the rich got richer faster, their piece of the pie grew larger. The wealthiest 1% of people increased their share of total income by 10%. Everyone else saw their piece of the pie shrink by 1%-2%. Even though the income going to the poor improved, they fell further behind when compared to the richest. As a result, economic mobility decreased.

During this same period, average wages remained flat. That’s despite an increase in worker productivity of 15%. Corporate profits increased by 13% per year.

The US has never had a properly funded public-health system. And the Trump administration has been persistently trying to cut funding and capacity for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, among other critical institutions.

Child Poverty By Country

On top of these self-inflicted wounds, an overly “financialized” business sector has been siphoning value out of the economy by rewarding shareholders through stock-buyback schemes, rather than shoring up long-run growth by investing in research and development, wages, and worker training. As a result, households have been depleted of financial cushions, making it harder to afford basic goods like housing and education.

The U.S.’s social safety net is more a loose patchwork unprepared to handle a crisis like the pandemic, relying on disconnected public programs and old technology. The federal government is relying on short-term measures directed to those affected

by the crisis, it does little to address the plight of those who were already economically vulnerable and those who will be long after this pandemic.

Disaster preparedness isn’t just the National Guard, personal protective equipment and bottled water anymore. This pandemic has shown that it is now also the ability to keep people economically afloat through a potentially prolonged and sudden financial crisis.

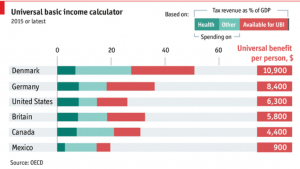

Amidst the debates about what can be done about the US economy, which appears to have less resiliency than Scandinavian countries with their strong social safety net, proposals for a Universal Basic Income (UBI) have surfaced.

The “Welfare Trap”

The modern welfare state emerged out of the ashes of the Great Depression and the Second World War. As governments across the Americas, Europe and Commonwealth tried to rebuild their economies, they began taking an active role in providing for the well-being of their poorer citizens through grants, services and money earmarked for purposes such as housing and food. Although such welfare systems have improved standards of living, most require an immense bureaucracy to administer benefits and to ensure that recipients meet strict qualification standards. Welfare critics have long argued that the administrative costs are huge and provide limited positive results; in some cases, they discourage people from finding jobs. The Universal Basic Income is seen as a viable alternative to the current welfare system is structured disincentive.

The welfare trap (or unemployment trap or poverty trap) asserts that taxation and welfare systems can jointly contribute to keep people on social insurance because the withdrawal of means-tested benefits that comes with entering low-paid work causes there to be no significant increase in total income.

An individual sees that the opportunity cost of returning to work is too great for too little a financial return, and this can create a perverse incentive to not work. In the United States, where government benefit payments are colloquially referred to as “welfare”, the welfare trap often indicates that a person is completely dependent on benefits, with little or no hope of self-sufficiency.

This concept may include other adverse effects of welfare such as on the family structure. It may encourage the increase in the numbers of single-mother families and divorce rates, as individuals see a distinct benefit in such a lifestyle.

If a person on welfare finds a part-time job that will pay the minimum wage of $5 per hour for eight hours per week (totaling $40), and, of the amount earned per week, $20 is deducted from welfare, there is a net gain of only $20. If the government imposes taxes on the $40, at say 15% ($6), and there may be extra child-care and commuting costs as well since that the person can no longer remain at home all day, the person is now worse off than before getting the job. This result occurs despite performing eight hours of work per week that is productive to society.

A welfare trap is an example of a perverse incentive. The welfare recipient, such as the one above, has an incentive to avoid raising productivity because the resulting income gain is not enough to compensate for the costs of increased work effort

A 2013 Cato Institute study claimed that workers could accumulate more wealth from the welfare system than they could from a minimum wage job in at least nine European countries. In three of them, namely Austria, Croatia and Denmark, the marginal tax rate was nearly 100%.

Proponents of universal basic income claim that it could eliminate welfare traps by removing conditions to receive such an income, but large-scale experiments have not yet produced clear results.

What is the Universal Basic Income (UBI)?

Basic income, also called Universal Basic Income (UBI), citizen’s income, citizen’s basic income, basic income guarantee, basic living stipend, guaranteed annual income, or “universal demogrant,|” is a theoretical governmental public program for a periodic payment delivered to all on an individual basis without a means test or work requirement.

Basic income can be implemented nationally, regionally, or locally. An unconditional income that is sufficient to meet a person’s basic needs (at or above the poverty line) is sometimes called a full basic income, while if it is less than that amount, it is sometimes called partial. A welfare system with some characteristics similar to those of a basic income is a negative income tax in which the government stipend is gradually reduced with higher labor income. Some welfare systems are sometimes regarded as steps on the way to a basic income, but because they have conditions attached, they are not basic incomes. One such system is a guaranteed minimum income system, which raises household incomes to a specified minimum. For example, Bolsa Família in Brazil was restricted to low-income families, and recipient families’ children are obligated to attend school.

History of the Universal Basic Income Idea

The idea of a state-run basic income dates back to the early 16th century when Sir Thomas More’s Utopia depicted a society in which every person receives a guaranteed income. In the late 18th century, English radical Thomas Spence and American revolutionary Thomas Paine both declared their support for a welfare system that guaranteed all citizens a certain income. Nineteenth-century debate on basic income was limited, but during the early part of the 20th century, a basic income called a “state bonus” was widely discussed. In 1946 the United Kingdom implemented unconditional family allowances for the second and subsequent children of every family. In the 1960s and 1970s, the United States and Canada conducted several experiments with negative income taxation, a related welfare system. Since the 1980s and onward, the debate in Europe took off more broadly, and since then, the debate has expanded to many countries around the world.

The first to develop the idea of social insurance was Marquis de Condorcet (1743–1794). After playing a prominent role in the French Revolution, he was imprisoned and sentenced to death. While in prison, he wrote the Esquisse d’un tableau historique des progrès de l’esprit humain(published posthumously by his widow in 1795), whose last chapter described his vision of a social insurance and how it could reduce inequality, insecurity, and poverty. Condorcet mentioned, very briefly, the idea of a benefit to all children old enough to start working by themselves and to start up a family of their own. He is not known to have said or written anything else on this proposal, but his close friend and fellow member of the Constitutional Convention Thomas Paine (1737–1809) developed the idea much further, a couple of years after Condorcet’s death.

The first social movement for basic income developed around 1920 in the United Kingdom. Its proponents included: philosopher Bertrand Russell who argued for a new social model that combined the advantages of socialism and anarchism, and that basic income should be a vital component in that new society; Dennis and Mabel Milner, a Quaker married couple in the Labour Party, published a short pamphlet entitled “Scheme for a State Bonus” that argued for the “introduction of an income paid unconditionally on a weekly basis to all citizens of the United Kingdom.” They considered it a moral right for everyone to have the means to subsistence, and thus it should not be conditional on work or willingness to work; C. H. Douglas was an engineer who became concerned that most British citizens could not afford to buy the goods that were produced, despite the rising productivity in British industry. His solution to this paradox was a new social system he called social credit, a combination of monetary reform and basic income.

In the UK, in 1944 and 1945, the Beveridge Committee, led by the British economist William Beveridge, developed a proposal for a comprehensive new welfare system of social insurance, means-tested benefits, and unconditional allowances for children. Committee member Lady Rhys-Williams argued that the incomes for adults should be more like a basic income. She was also the first to develop the negative income tax model.Her son Brandon Rhys Williams proposed a basic income to a parliamentary committee in 1982, and soon after that in 1984, the Basic Income Research Group, now the Citizen’s Basic Income Trust, began to conduct and disseminate research on basic income.

In the 1960s and 1970s, some welfare debates in the United States and Canada included discussions of basic income. Six pilot projects were also conducted with the negative income tax. President Richard Nixonproposed a massive overhaul of the federal welfare system, replacing many of the federal welfare programs with a negative income tax – a proposal favored by economist Milton Friedman. Nixon said, “The purpose of the negative income tax was to provide both a safety net for the poor and a financial incentive for welfare recipients to work.” Congress eventually approved a guaranteed minimum income for the elderly and the disabled, not for all citizens.

In the late 1970s and the 1980s, basic income was more or less forgotten in the United States, but it started to gain some traction in Europe. Basic Income European Network, later renamed to Basic Income Earth Network, was founded in 1986 and started to arrange international conferences every two years. From the 1980s, some people outside party politics and universities took an interest. In West Germany, groups of unemployed people took a stance for the reform.

Since 2010, basic income again became an active topic in many countries. Basic income is currently discussed from a variety of perspectives—including in the context of ongoing automation and robotization, often with the argument that these trends mean less paid work in the future, which would create a need for a new welfare model. Several countries have run pilot programs or are planning for local or regional experiments with basic income.

Here are examples in the United States and other countries

United States

Alaska has had a guaranteed income program since 1982. The Alaska Permanent Fund paid each resident an average of $1,606 in 2019, all out of oil revenues. Almost three-fourths of recipients save it for emergencies. In 2017, the Hawaii state legislature passed a bill declaring that everyone is entitled to basic financial security. It directed the government to develop a solution, which may include a guaranteed income. In Oakland, California, the seed accelerator Y Combinator will pay 100 families between $1,000 and $2,000 a month. In 2019, Stockton, California, began a two-year pilot program. It’s giving $500 a month to 125 local families. It hopes to keep families together, and away from payday lenders, pawn shops, and gangs. About 43% of the recipients are still working. Most of the others were taking care of relatives, disabled, retired, or students. Chicago, Illinois, is considering a pilot to give 1,000 low-income families $1,000 a month.

Canada

Canada was one of the first western countries to experiment with UBI. The province of Manitoba, Canada experimented with Mincome, a basic guaranteed income, in the 1970s. In the town of Dauphin, Manitoba, labor only decreased by 13%, much less than expected. A three-year basic income pilot that the Ontario provincial government, Canada, launched in the cities of Hamilton, Thunder Bay and Lindsay in July 2017. It gave 4,000 Ontario residents living in poverty C$17,000 a year or C$24,000/couple at a cost of C$50 million annually. Although called basic income, itwas only made available to those with a low income and funding would be removed if they obtained employment, making it more related to the current welfare system than actual basic income. The pilot project was cancelled on 31 July 2018 by the newly elected Progressive Conservative government under Ontario Premier Doug Ford.

Finland

Finland gave 2,000 unemployed people 560 euros a month for two years, beginning in January 2017. In April 2018, the Finnish government rejected a request for funds to extend and expand the program from Kela (Finland’s social security agency). Despite the decision to cancel the project, the recipients said it reduced stress. They said it gave them more incentive to find a good job or start their own business.

Scotland

Scotland has committed £250,000 to four pilot areas that pays every citizen for life. Retirees would receive 150 pounds a week. Working adults would get 100 pounds and children under 16 would be paid 50 pounds a week.

Taiwan

Taiwan may vote on a basic income. Younger people have left rural areas in search of decent wages. Some have even left the country to look for work. A guaranteed income might keep them from emigrating. It would also help the senior citizens left behind who live in poverty. The country only spends 5% of its gross domestic product on welfare programs. The average for developed countries is 22%. Under the proposal, the government would pay NT$6,304 per month for children under 18 and NT$12,608 per month for adults. It would cost NT$3.4 trillion, or 19% of GDP. To fund it, Taiwan would levy a 31% tax on earnings above NT$840,000 per year. As a result, the program would raise the incomes of two-thirds of the population. The richer third would lose NT$710 billion.

Brazil

Bolsa Famíliais a large social welfare program in Brazil that provides money to many poor families in the country. The system is related to basic income, but has more conditions, like asking the recipients to keep their children in school until graduation. Brazilian Senator Eduardo Suplicy championed a law that ultimately passed in 2004 that declared Bolsa Família a first step towards a national basic income. However, the program has not yet been expanded in that direction.

African Countries

Omitara, one of the two poor villages in Namibiawhere a local basic income was tested in 2008–2009 and ended in 2009. A project called Eight in a village in Fort Portal, Uganda, that a nonprofit organization launched in January 2017 which provides income for 56 adults and 88 children through mobile money.Social Income started paying out basic incomes in form of mobile money in 2020. The recipients are people in need in Sierra Leone. The international initiative is financed by contributions from people in the Global North, who continuously donate 1% of their monthly pay checks. A study of 63 Kenyan villages found that nine transfers of $45 a month improved local consumption and well-being. It increased consumption of food, medicine, education, and social events without increasing alcohol and tobacco use. The households were also able to increase investments in livestock, furniture, and home improvements. In 2011, GiveDirectly, Inc. began distributing cash to poor households in Kenya via mobile phones.

India

Basic income trials in several villages in India, whose government has proposed a guaranteed basic income for all citizens. In a study in several Indian villages, basic income in the region raised the education rate of young people by 25%.The Rythu Bandhu schemeis a welfare scheme started on 10 May 2018 aimed towards helping farmers that is being implemented by the state of Telanganain India, where each farmland owner gets a fixed amount of money ₹4,000 per acre twice a year for rabiand kharifharvests.

The Arguments for UBI

- Workers could afford to wait for a better job or better wages.

- People would have the freedom to return to school or stay home to care for a relative.

- Citizens could have simple, straightforward financial assistance that minimizes bureaucracy.

- The government would spend less to administer the program than with traditional welfare.

- Payments would help young couples start families in countries with low birth rates.

- The payments could help stabilize the economy during recessionary periods.

- An unconditional basic income would enable workers to wait for a better job or negotiate better wages. They could improve their marketability by going back to school. They could even quit their job to care for a relative.

- It would remove the problem with existing welfare programs that keep people “trapped in poverty.” If welfare recipients make too much, they lose food stamps, free medical care, and housing vouchers. This is a form of structural inequality that prevents the poor from getting enough wealth to better their lives.

- A simple cash payment would cut down on bureaucracy. Current welfare programs are also complicated for administrators and recipients. A universal income would replace housing vouchers, food stamps, and other programs.Cash payments that went to everyone would eliminate costly income-verification paperwork. Only applicants with low incomes qualify for means-tested programs. Conservative Utah Senator Mike Lee told the Heritage Foundation, “There’s no reason the federal government should maintain 79 different means-tested programs.”

- Some countries are concerned about falling birth rates. A guaranteed income would give young couples the confidence they need to start a family.

- It would also provide workers the confidence to bid up wages.

- From a macro viewpoint, it would give society a much-needed ballast during a recession or weathering the storm of disasters such as a pandemic.

Public Polls Show Increasing Support for UBI

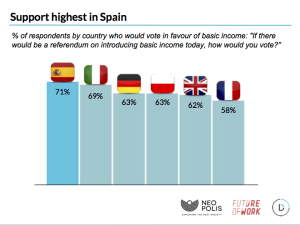

Support for a universal basic income varies widely across Europe, as shown by a recent wave of the European Social Survey. A high share of the population tends to support the scheme in southern and central eastern European Union countries, while support tends to be lower in western European countries such as France and Germany, and even lower in Scandinavian countries such as Norway and Sweden. Support for a UBI in the U.S. and Canada is increasing.

Individuals who face greater economic insecurity, for instance because of low income and unemployment tend to be more supportive of a basic income. Overall, support tends to be on average higher in countries where existing unemployment benefits are not generous and/or where the unemployed are activated in the sense that the receipt of benefits is conditional on certain job search behavior.

The poll from University of Chicago’s GenForward Survey Project indicates that 51 percent of Americans between the ages of 18-36 support a federally-funded basic income of $1,000 per month for all U.S residents, a plan touted by businessman Andrew Yang during his 2020 Democratic presidential campaign.

Younger Americans also want to see the current U.S. healthcare system expanded at the federal level, the poll finds, with 35 percent supporting the creation of a so-called “public option,” or a public healthcare plan that would compete with private insurers. Another 17 percent said that the U.S. healthcare system should be replaced with a single-payer “Medicare for All” system.

In comparison, just 21 percent said that they supported keeping the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, and building off it while 17 percent supported repealing that plan entirely.

Economic anxiety remains a serious concern for younger Americans, which may contribute to their support for expansions of the social safety net. According to the survey, 59 percent of young adults said that they were at least somewhat worried about their ability to afford a surprise $1,000 expense in their personal lives, while only 30 percent said they were not worried about such a possibility.

A POLITICO/Morning Consult poll conducted between the 14th and 17th September 2017 surveying 1,994 registered US voters, found that, of those asked whether they would support or oppose “a proposal in which the government would provide all Americans a regular, unconditional sum of money, sometimes referred to as universal basic income”, 43% either “strongly supported” or “somewhat supported” the idea.

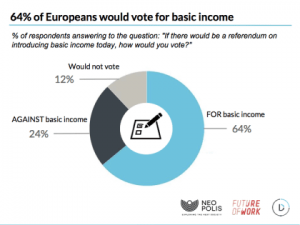

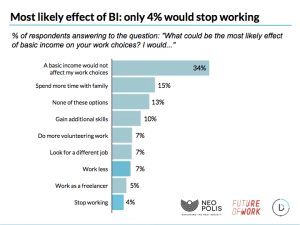

According to a European NeoPolis/Future of Work survey carried out in April 2016, about 58% of the people are aware of basic income, and 64% would vote in favor of the policy if there was a referendum about it.

Other Polls:

- A poll conducted by the University of Chicago indicates that 51% of Americans from the ages of 18–36 support a monthly basic income of $1,000.Support for universal basic income spans the political spectrum, with conservatives, progressives, and libertarians all having camps both for and against basic income.

- 2008: an official petition for basic income was started in Germany by Susanne Wiest.The petition was accepted and Susanne Wiest was invited for a hearing at the German parliament’s Commission of Petitions.

- 2013–2014: a European Citizens’ Initiative collected 280,000 signatures demanding that the European Commission study the concept of an unconditional basic income.

- 2015: a citizen’s initiative in Spain received 185,000 signatures, short of the required number to mandate that parliament discuss the proposal.

- 2016: the world’s first universal basic income referendum in Switzerland was rejected with a majority.

- Also in 2016, a poll showed that 58% of the EU’s population are aware of basic income, and 65% would vote in favor of the idea.

- 2019: in a September poll conducted by The Hilland HarrisX, 49% of U.S. registered voters support basic income, up 6% from a similar survey conducted six months prior.

- 2019: In November an Austrian initiative received approximately 70,000 signatures but failed to reach the 100,000 signatures needed for a parliamentary discussion. The initiative was started by Peter Hofer, his proposal suggested a basic income of 1200 € for every Austrian citizen.

- 2020: A public poll by YouGov in 2020 has found that the majority of the public in the United Kingdom support a universal basic income, with only 24% unsupportive. In March 2020, over 170 MPs and Lords from all political parties signed a letter calling on the government to introduce a basic income during the coronavirus pandemic.

Key Experts and Leaders Support UBI

In 2018, Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes outlined his plan in his book “Fair Shot.”5 He argued that U.S. workers, students, and caregivers making $50,000 or less a year should receive a guaranteed income of $500 a month.

“Cash is the best thing you can do to improve health outcomes, education outcomes and lift people out of poverty,” Facebook founder Chris Hughes said. Hughes’ guaranteed income plan is financed by taxes on the top 1%. It would work through a modernization of the earned income tax credit.

To Hughes, it’s the only solution to an economy where “a small group of people are getting very, very wealthy while everyone else is struggling to make ends meet.” Hughes said automation and globalization have destroyed the employment market. It’s created a lot of part-time, contract, and temporary jobs. But those positions aren’t enough to provide a decent standard of living.

Sir Richard Branson said a guaranteed income is inevitable.Automation has fundamentally changed the structure of the U.S. economy. Billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk told the National Governors Association that job disruption caused by technology was “the scariest problem to me,” admitting that he had no easy solution. Musk and other entrepreneurs see UBI as way to provide a cushion and a buffer to give humans time to retrain themselves to do what robots can’t do. Some believe that it might even spawn a new wave of entrepreneurs, giving those displaced workers a shot at the American Dream.

Prominent contemporary advocates include Economics Nobel Prize winners Peter Diamond and Christopher Pissarides,political philosopher Philippe Van Parijs,former finance minister of Greece Yanis Varoufakis, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, eBay founder Pierre Omidyar,and entrepreneur and non-profit founder Andrew Yang, who ran for the Democratic nomination for the 2020 United States presidential election on a platform of instituting a $1,000-a-month universal basic income.

In addition to Yang, Democratic politicians Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Tulsi Gabbard have advocated for universal basic income in response to the COVID-19 pandemic; the latter suggested that it be a temporary measure until the crisis subsides. On 13 March 2020, Democratic representatives Ro Khanna and Tim Ryan introduced legislation to provide payments to low-income citizens during the crisis via an earned income tax credit. On 16 March, Republican senators Mitt Romney and Tom Cotton stated their support for a $1,000 basic income, the former saying it should be a one-time payment to help with short-term costs.

Senator Bernie Sanders has called for $2,000 in monthly basic income to help “every person in the United States, including the undocumented, the homeless, the unbanked, and young adults excluded from the CARES Act”. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has also suggested that a basic income could be “worthy of attention”.

On 12 April 2020, Pope Francis called for the introduction of basic income in response to coronavirus.

Renowned economist Milton Friedman proposed a negative income tax. The poor would receive a tax credit if their income fell below a minimum level. It would be equivalent to the tax payment for the families earning above the minimum level.

Citizen Capitalism is a supplemental income program proposed by the legal scholar Lynn Stout and her co-authors Tamara Belinfanti and Sergio Gramitto in their book Citizen Capitalism: How A Universal Fund Can Provide Influence and Income to All which was published in 2019. In the book, Stout and her co-authors propose the building of a not-for-profit universal fund composed of shares donated by corporations and philanthropic individuals in which every American would receive one share.

These shares could not be sold, bequeathed, donated, or borrowed against, but each “citizen shareholder” would receive an even portion of the net dividends paid out by shares in the fund, therefore contributing to the amelioration of income inequality. Each shareholder would also receive additional influence in the form of a vote (corresponding to their shares in the fund), providing in theory for a significantly expanded degree of citizen engagement in the role that public corporations play in American society.

His new book Fair Shot: Rethinking Inequality and How We Earn outlines Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes provides his views on UBI . He says we can “provide every single American stability through cash” by providing a monthly $500 supplement to lower-middle income taxpayers through the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC. He would expand EITC to include child care, elder care, and education as types of work that would be eligible for EITC. (Currently if the jobs are unpaid jobs, they are not eligible.)

Hughes contends that this would cut poverty in America by half. According to his numbers, right now the EITC costs the US $70 billion a year, and his UBI proposal would tack on an additional $290 billion. Citing research by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman showing that less than 1 percent of Americans control as much wealth as 90 percent of Americans, Hughes’ plan to pay for that expansion involves increasing the income tax for the top 1 percent, or people earning more than $250,000 a year, to 50 percent from 35 percent, and treating capital gains as income—moving long-term capital gains from 20 percent to 50 percent, hitting the wealthiest the hardest.

Projected rates of urbanization, alongside increasing levels of urban povertyand inequality, are forcing more and more cities to invest in anti-poverty measures such as affordable housing and childcare. There is no doubt that these help individuals. However, more often than not, such programs are inadequately equipped to predict the full spectrum of human behavior. Ultimately, they are administratively incapable of catering to all the diverse wants and needs of citizens.

The freedom to make one’s own choices is an essential component of human dignity and autonomy. Some may even regard this freedom as a form of wealth. Conversely, poverty is the absence of choice. People who are living in poverty have fewer choices when it comes to controlling even the most basic areas of their lives, including their health, living conditions, employment and education.

As an unconditional money transfer, the advantage of Universal Basic Income (UBI) is its ability to change deep-rooted incentive structures. A true alleviation of poverty requires shifting the motivations that drive the rest of society. Our notions of work and welfare are informed by the deep-rooted norms and cultures of individuals who are often full-time, wage-earning, insured members of society – most of whom have never faced a lack of alternatives.

Consequently, the one-size-fits-all approach to work and income has done little to advance the overall choice architecture for individuals trapped in poverty. In short, UBI can maximize choice for those living in poverty by minimizing the choice-reducing behaviors of those who are not.

UBI encourages the “decommodification” of human labor by changing the way in which the majority conceives work. It does so by distinguishing the manner in which human labor manifests itself in our lives, i.e., through paid and unpaid work. We perceive hours spent in paid and unpaid work as competing with each other. However, the right to work for pay and the right not to work for pay should be entirely compatible with each other. In this regard, UBI has the power to reimagine our work culture and remove existing biases found in labor markets in four main ways.

From a human rights perspective, unconditionally providing income outside of employment allows the realization of a full right to work, since it gives people protection against unemployment, and consequently the ability to refuse precarious employment.

From a sociological perspective, providing people with a secure economic base revitalizes personal and societal relationships, by giving people who wish to work for pay the choice to seek a job they find meaningful.

From a gender lens, UBI supports those choosing to undertake unpaid work such as domestic work, caregiving for the vulnerable and volunteer work. Often, unpaid work sustains other types of socially useful work but goes undervalued and uncompensated.

From a free market perspective, UBI produces a more competitive labor market by reducing the monopoly that paid work has over unpaid work. This balances the playing field between employers and workers, since employers must compete to attract talent – for example, with better wages and more flexible hours.

It is no secret that cities are first and foremost poised to benefit from technological innovation. Investment in inclusive prosperity is a necessary goal in a future where paid work is scarce and people struggle to earn enough to meet their basic necessities. Millions of jobs will as the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) continues to disrupt labor markets. Indeed, today’s accelerated rates of technological innovation, globalization, climate change, demographic shifts and geopolitical transformations and now the threat of pandemics make the landscape of the 4IR unpredictable and ruthless in urban centers.

At the same time, there exist entire populations that have yet to benefit from the First (manufacturing), Second (technology), and Third (digital) Industrial Revolutions. We have already seen civic unrest in cities where rates of poverty and inequality are rising. In addition to reimagining the culture of work, cities must look to adopt UBI as a preventative strategy to assuage existing mass frustrations resulting from skills shortages, unemployment and systemic inequalities. Both cities and businesses must come together to create inclusive economic development.

Apart from lifting millions out of poverty, some UBI proposals promote efficiency and a shrinking of the federal bureaucracy, which currently in the US has 79 means tests. Creating a single point of access would also make many recipients’ lives easier. If they knew they had something to fall back on, workers could negotiate better wages and conditions, or go back to school, or quit a low-paying job to care for a child or aging relative. And with an unconditional basic income, workers wouldn’t have to worry about how making more money might lead to the loss of crucial benefits.

In the Financial Times, Martin Wolf has contemplated a guaranteed income’s ability to help society adjust to the disappearance of low-skill, low-wage jobs. Is it feasible? It depends on the size and scope of the program, but Danny Vinik crunched some numbers at Business Insider: “In 2012, there were 179 million Americans between the ages of 21 and 65 (when Social Security would kick in). The poverty line was $11,945. Thus, giving each working-age American a basic income equal to the poverty line would cost $2.14 trillion.”

Cutting all federal and state benefits for low-income Americans would save around a trillion dollars per year, so there would still be a significant gap to be closed by revenue increases like higher taxes on the 1% or corporations or closing existing tax loopholes.

Alternatively, a guaranteed income could be means-tested, or just offered at a lower level. InThe Atlantic, Matt Bruenig and Elizabeth Stoker argued policymakers could halve poverty by cutting a $3,000 check to Americans of all ages.

Proponents of guaranteed income schemes argue that poor people will benefit more from unrestricted funds than from current welfare systems, which tend to have stringent requirements that often leave recipients trapped in poverty. “Universal basic income is about giving people cash without question, and trusting that they know how to use it in the most-effective way they can,” says Luke Martinelli, an economist at the University of Bath, UK.

Much of the resurgent interest in UBI has come from Silicon Valley. Tech titans and the academics around them are concerned that the robots and artificial intelligence they’ve built will rapidly displace humans in the workforce, or at least push them into dead-end jobs. Some researchers say robots will replace the low-paying jobs people don’t want, while others maintain people will end up getting the worst jobs not worthy of robots.

Underpinning the Silicon Valley argument for UBI is the belief in exponential growth powered by science and technology, as described by Peter Diamandis in his book Abundance: The Future is Better Than You Think. Diamandis contends that technological progress, including gains in health, the power of computing, and the development of machine intelligence, among other things, will lead to a kind of technological transcendence that makes today’s society look like how we view the Dark Ages. He argues that the human mind is unable to intuitively grasp this idea, and so we constantly underestimate long-term effects. If you plot progress out a few decades, Diamandis writes, we end up with unimaginable abundance: “We will soon have the ability to meet and exceed the basic needs of every man, woman, and child on the planet. Abundance for all is within our grasp.”

Basic income in numbers in the U.S.

What tends to go unrealized about the idea of basic income, and this is true even of many economists – but not all – is that it represents a net transfer. In the same way it does not cost $20 to give someone $20 in exchange for $10, it does not cost $3 trillion to give every adult citizen $12,000 and every child $4,000, when every household will be paying varying amounts of taxes in exchange for their UBI. Instead it will cost around 30% of that, or about $900 billion, and that’s before the full or partial consolidation of other programmes and tax credits immediately made redundant by the new transfer. In other words, for someone whose taxes go up $4,000 to pay for $12,000 in UBI, the cost to give that person UBI is $8,000, not $12,000, and it’s coming from someone else whose taxes went up $20,000 to pay for their own $12,000. However, even that’s not entirely accurate, because the consolidation of the safety net and tax code UBI allows could drive the total price even lower.

Now, this idea of replacing existing programs can scare some just as it appeals to others, but the choice is not all or nothing: partial consolidation is possible. As an example of partial consolidation, because most seniors already effectively have a basic income through social security, they could either choose between the two, or a percentage of their social security could be converted into basic income. Either way, no senior would earn a penny less than now in total, and yet the UBI price tag could be reduced by about $220 billion. Meanwhile, just a few examples of existing revenue that could and arguably should be fully consolidated into UBI would likely be food and nutrition assistance ($108 billion), wage subsidies ($72 billion), child tax credits ($56 billion), temporary assistance for needy families ($17 billion), and the home mortgage interest deduction (which mostly benefits the wealthy anyway, at a cost of at least $70 billion per year). That’s $543 billion spent on UBI instead of all the above, which represents only a fraction of the full list, none of which need be healthcare or education.

So what’s the true cost?

The true net cost of UBI in the US is therefore closer to an additional tax revenue requirement of a few hundred billion dollars – or less – depending on the many design choices made, and there exists a variety of ideas out there for crossing such a funding gap in a way that many people might prefer, that would also treat citizens like the shareholders they are (virtually all basic research is taxpayer funded), and that could even reduce taxes on labour by focusing more on capital, consumption, and externalities instead of wages and salaries. Additionally, we could eliminate the $540 billion in tax expenditures currently being provided disproportionately to the wealthiest, and also some of the $850 billion spent on defense.

Universal basic income is thus entirely affordable. UBI does not exist outside the tax system unless it’s provided through pure monetary expansion or extra-governmental means. In other words, yes, Bill Gates will get $12,000 too but as one of the world’s wealthiest billionaires he will pay far more than $12,000 in new taxes to pay for it. That however is not similarly true for the bottom 80% of all US households, who will pay the same or less in total taxes.

The government sends the check, but plans differ on who funds the income. Some plans call for a tax increase on the wealthy, while others say corporations should be taxed.

What About the Impact on People’s Motivation to Work?

But what about people then choosing not to work? Isn’t that a huge burden too? Well that’s where things get really interesting. For one, conditional welfare assistance creates a disincentive to work through removal of benefits in response to paid work. If accepting any amount of paid work will leave someone on welfare barely better off, or even worse off, what’s the point? With basic income, all income from paid work (after taxes) is earned as additional income so that everyone is always better off in terms of total income through any amount of employment – whether full time, part time or gig. Thus basic income does not introduce a disincentive to work. It removes the existing disincentive to work that conditional welfare creates.

Fascinatingly, improved incentives are where basic income really shines. Studies of motivation reveal that rewarding activities with money is a good motivator for mechanistic work but a poor motivator for creative work. Combine that with the fact that creative work is to be what’s left after most mechanistic work is handed off to machines, and we’re looking at a future where increasingly the work that’s left for humans is not best motivated extrinsically with money, but intrinsically out of the pursuit of more important goals. It’s the difference between doing meaningless work for money, and using money to do meaningful work.

Basic income thus enables the future of work, and even recognizes all the unpaid intrinsically motivated work currently going on that could be amplified, for example in the form of the $700 billion in unpaid work performed by informal caregivers in the US every year, and all the work in the free/open source software movement (FOSSM) that’s absolutely integral to the internet.

There is also another way basic income could affect work incentives that is rarely mentioned and somewhat more theoretical. UBI has the potential to better match workers to jobs, dramatically increase engagement, and even transform jobs themselves through the power UBI provides to refuse them.

A truly free market for labor

How many people are unhappy with their jobs? According to Gallup, worldwide, only 13%of those with jobs feel engaged with them. In the US, 70% of workers are not engaged or actively disengaged, the cost of which is a productivity loss of around $500 billion per year. Poor engagement is even associated with a disinclination to donate money, volunteer or help others. It measurably erodes social cohesion.

At the same time, there are those among the unemployed who would like to be employed, but the jobs are taken by those who don’t really want to be there. This is an inevitable result of requiring jobs in order to live. With no real choice, people do work they don’t wish to do in exchange for money that may be insufficient – but that’s still better than nothing – and then cling to that paid work despite being the “working poor” and/or disengaged. It’s a mess.

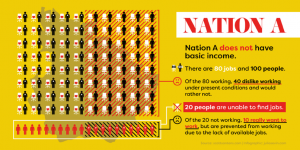

Take an economy without UBI. We’ll call it Nation A. For every 100 working-age adults there are 80 jobs. Half the work force is not engaged by their jobs, and half again as many are unemployed with half of them really wanting to be employed, but, as in a game of musical chairs, they’re left without a chair.

Basic income fundamentally alters this reality. By unconditionally providing income outside of employment, people can refuse to do the jobs that aren’t engaging them. This in turn opens up those jobs to the unemployed who would be engaged by them. It also creates the bargaining power for everyone to negotiate better terms. How many jobs would become more attractive if they paid more money or required fewer hours? How would this reorganizing of the labour supply affect productivity if the percentage of disengaged workers plummeted? How much more prosperity would that create?

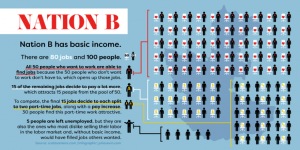

Consider now an economy with basic income. Let’s call it Nation B. For every 100 working age adults there are still 80 jobs, at least to begin with. The disengaged workforce says “no thanks” to the labour market as is, enabling all 50 people who want to work to do the jobs they want. To attract those who demand more compensation or shorter work weeks, some employers raise their wages. Others reduce the required hours. The result is a transformed labour market of more engaged, more employed, better paid, more productive workers. Fewer people are excluded, and there’s perhaps more scope for all workers to become self-employed entrepreneurs.

Simply put, a basic income improves the market for labor by making it optional. The transformation from a coercive market to a free market means that employers must attract employees with better pay and more flexible hours. It also means a more productive work force that potentially obviates the need for market-distorting minimum wage laws. Friction might even be reduced, so that people can move more easily from job to job, or from job to education/retraining to job, or even from job to entrepreneur, all thanks to more individual liquidity and the elimination of counter-productive bureaucracy and conditions.

Perhaps best of all, the automation of low-demand jobs becomes further incentivized through the rising of wages. The work that people refuse to do for less than a machine would cost to do it becomes a job for machines. And thanks to those replaced workers having a basic income, they aren’t just left standing in the cold in the job market’s ongoing game of musical chairs. They are instead better enabled to find new work, paid or unpaid, full-time or part-time, that works best for them.

Summary :The tip of a big iceberg

The idea of a Universal Basic Income is deceivingly simple sounding, but in reality it’s like an iceberg with far more to be revealed as you dive deeper. Its big picture price tag in the form of investing in human capital for far greater returns, and its effects on what truly motivates us are but glimpses of these depths. There are many more. Some are already known, like the positive effects on social cohesion and physical and mental health as seen in the 42% drop in crime in Namibia and the 8.5% reduction in hospitalizations in Dauphin, Manitoba. Debts tend to fall.

Entrepreneurship tends to grow. Other effects have yet to be discovered by further experiments. But the growing body of evidence behind cash transfers in general point to basic income as something far more transformative to the future of work than even its long history of consideration has imagined.

It’s like a game of Monopoly where the winning teams have rewritten the rules so players no longer collect money for passing Go. The rule change functions to exclude people from markets. Basic income corrects this. But it’s more than just a tool for improving markets by making them more inclusive; there’s something more fundamental going on.

Humans need security to thrive, and basic income is a secure economic base – the new foundation on which to transform the precarious present, and build a more solid future. That’s not to say it’s a silver bullet. It’s that our problems are not impossible to solve. Poverty is not a supernatural foe, nor is extreme inequality or the threat of mass income loss due to automation. They are all just choices. And at any point, we can choose to make new ones.

Based on the evidence we already have and will likely continue to build, I firmly believe one of those choices should be unconditional basic income as a new equal starting point for all.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.