By Ray Williams

August 2, 2019

Like many others I was shocked and dismayed to see and read the news about yet two more mass shootings with many dead and wounded in El Paso Texas and Dayton Ohio. These instances of domestic terrorism are added to a long list of shootings throughout the U.S. in 2019.

But what struck me was the balance in the news coverage. While they were positive stories about the positive and caring responses of people and communities, and commentaries about the need to take proactive action to unite people and bring safety and security to communities, the vast majority of the news coverage focused on the negative aspects of the tragic events—images of the scene of the carnage, police, weapons, and experts providing endless detail about the events. The negative stories far outweighed the positive.

While many of us frequently complain about “bad” or negative news in the media or stories we hear of daily, the evidence would suggest we continue to be attracted to it. Shouldn’t we prefer to hear positive and happy news?

A closer examination of this question may shed some light upon the current state of public affairs and personal experiences.

The Impact of the Media

Every day we watch, hear or read about another tragedy or national disaster occurring, desensitizing us to gun violence, corruption, human suffering and natural disasters. Most often, the pubic unites for moments or days to mourn or express other emotions and then resumes their daily lives after tweeting out a trending hashtag to shock, dismay or support. Are we becoming overexposed to negativity and heartbreak?

This lends itself to the question: Is there really more bad news than good news?

A study by the Pew Research Center for People & Press that examined the news stories from over 165 surveys shows that patterns in American news coverage has remained consistent and unchanging for the past 20 years. The study concluded that war and terrorism related stories have consistently remained the most interest-generating and therefore most extensively covered stories since 1986.

What accounts media’s acute focus on negative events over positive events? A simple answer is that “bad news sells.” Yet, despite the fact that this trend has been in place for the past two decades, patterns in viewership have altered significantly during this time. While in the 1980s, about 30 percent of Americans followed the news “very closely,” this number decreased by seven percent in the 1990s before rising to 30 percent again at the start of the 21st century.

Regardless of these fluctuations, Americans show the greatest interest in media reports about war and terrorism, with bad weather and natural disasters closely following, politics, crime and health falling in a middle-ground, and entertainment and science yielding the fewest viewers.

The fact that about 90 percent of news Americans hear is negative, the study concludes that there is not necessarily more bad news than good news occurring in the world. Rather, American audiences are simply more compelled toward negative news than positive news.

The City Reporter conducted an experiment to test this explanation. After changing the perspective of their stories to appear more positive and covering generally more uplifting stories for one day, the news audience viewing decreased by two thirds. Even small changes made to focus on the positives, such as saying that there is no disruption in traffic despite bad weather, changed viewer behavior.

Some media experts have argued that the media’s focus on negativity is not found in the ratio of bad news to good news, but instead in the psychological human tendency remember negative memories more clearly than positive ones. As neuroscientist Rick Hansen has said,“The brain is like Velcro for negative experiences and Teflon for positives ones.”

This tendency may not only be the cause of the media’s bias toward negative stories but also an effect of this bias. While news outlets do have to ensure that their stories are audience-generating to attract sponsor revenue, the stories they choose to cover also play an important role in shaping their audience’s outlook on the world and opinions on current events.

Author of the Pew Research Center’s media study, Michael J. Robinson, argues the media’s choice in stories plays more of a role on the audience’s preferences than the other way around:“The national news audience does not shift its news diet nearly so quickly as news organizations shift their news menu.”

By focusing primarily on negative news, Robinson contends, the media suggests that there is primarily negative things and people in the world which provides a dark or despairing outlook on the world. This can fuel a rather pessimistic society and dissuade people from seeking the good in the world, or restraining the potential actions society can to remedy the negative issues that people face (climate change?).

Also, news outlets can exaggerate minor negative stories in a fast news cycle, when there are no “big stories” to report, in order to increase viewership. And technology has aided the rapid- fire negative news cycle by including “ticker-tape” message banners scrolling across the TV screens as though the main screen was insufficient to sustain the viewers’ attention.

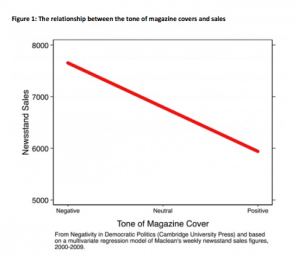

News agencies seek audiences, therefore advertising sales, which is attracted by negative stories. For example, as the figure below illustrates, based on a study by Cambridge University of the Canadian news magazine, Macleans, newsstand magazine sales increased by roughly 30 per cent when the cover was negative rather than positive. Other research by Mark Trussler and Stuart Soroka, published in the International Journal of Press/Politics, suggests that even when participants say that they would like more positive news, they still select online news stories that are predominantly negative.

Echoing Rick Hanson’s quotation on the brain’s preferences, Stuart Soroka and Stephen McAdams, writing in the journal Political Communication, argue that humans’ predisposition to be neurologically or physiologically towards focusing on negative has its roots in an evolutionary-biological account of how humans decide what to pay attention to. They contend: “It is evolutionarily advantageous to prioritise negative information, because the potential costs of negative information far outweigh the potential benefits of positive information.”

Is Social Media Different?

In a Huffington Post article by Arianna Huffington, which contrasts social media from mainstream media, she argues for the importance – and popularity – of positive news. Huffington draws in part on recent work published in the New York Times, suggesting that positive stories are more likely to be shared on social networks. This trend in sharing, she suggests, provides evidence that the “if it bleeds, it leads” approach to gaining audiences is misguided. News readers, she argues, want more positive news content.

Some experts would disagree with Huffington. Sharing news content on social media, they say,is a fundamentally different thing from selecting and reading articles; even as we may tend to forward positive material via social media, our news-reading habits may still prioritise negative information.

Sorokin says that future research might consider the implications that social media have on the tone of the news content that we receive. If we increasingly receive news content through social media, as a Pew Center research study suggests, and if social media users tend to forward positive rather than negative information, as John Tiernay argues in the New York Times, then we might expect the tone of our news stream to become more positive overall. Whether this leads to a more informed or attentive electorate is another matter, however. We may be better informed about successful policy initiatives. We may alternatively lose (even more) interest in politics.

What Does the Research Say?

Economics correspondent Paul Solmon did an interesting piece on the cascading effect that consumer pessimism has on our willingness to spend. He said that we are in a state of “learned helplessness”. At the worst, continual bad news can even stimulate a state of depression, and people who concentrate on all the bad news work themselves up emotionally and become much more likely to make unwise decisions, like selling all their investments at a huge loss or halting their consumer spending entirely. Even people who don’t watch television or read newspapers are getting hit with nuggets of negativity through social networking and informal conversations.

When everyone was talking about the recent recession, “we all feel like something has to change, even if nothing has changed,” says Dan Ariely, author of Predictably Irrational, People may be scared to spend money, scared about losing their jobs and in doing so will restrain their spending. Yet look closely. Consumer sales in entertainment, and drugs like Viagra have increased. Viacom’s sales were down from last year but still profitable. Best practice companies with a long-term view are weathering the recession quite well. Social networking in many forms is expanding rapidly.

Media studies show that bad news far outweighs good news by as much as seventeen negative news reports for every one good news report. Why? The answer may lie in the work of evolutionary psychologists and neuroscientists. Humans seek out news of dramatic, negative events. These experts say that our brains evolved in a hunter-gatherer environment where anything novel or dramatic had to be attended to immediately for survival. So while we no longer defend ourselves against saber-toothed tigers, our brains have not caught up.

Many studies have shown that we care more about the threat of bad things than we do about the prospect of good things. Our negative brain tripwires are far more sensitive than our positive triggers. We tend to get more fearful than happy. And each time we experience fear we turn on our stress hormones.

Another explanation comes from probability theory. In essence, negative and unusual things happen all the time in the world. In his book, Innumeracy,John Allen Paulos explains that if the news is about a small neighborhood of 500 or 5,000, then the possibility that something unusual has happened is low. Unusual things don’t happen to individual people very often.

That’s why very local news like a neighborhood newsletters tends to have less bad news. But in a large city of 1 million, dramatic and negative incidents happen all the time. But most people watch national or worldwide media where news reports come in from large cities at a large scale, so the prevalence of negative stories increase. Add the size of social networking communication, and we expand geometrically bad news. So from evolutionary and neuro-scientific and probability perspectives, our brains, from an evolutionary perspective, are “hard-wired” to look for negative. And it’s part of human nature to share that news.

Researchers Marc Trussler and Stuart Soroka, set up an experiment, at McGill Universityfor “a study of eye tracking”. The volunteers were first asked to read political stories from a news website so that a camera could make some baseline eye-tracking measures. It was important, they were told, that they actually read the articles, so the right measurements could be prepared, but it didn’t matter what they read.

After this ‘preparation’ phase, they watched a short video, and then they answered questions on the kind of political news they would like to read.

Trussler and Soroka reported participants often chose stories with a negative tone rather than neutral or positive stories. People who were more interested in current affairs and politics were particularly likely to choose the bad news.

Here’s the interesting part. When the researchers asked what kind of news the participants preferred, they said they preferred good news. And yet, they also said that the media was too focussed on negative stories.

Trussler and Soroka say their experiment is evidence of a so called “negativity bias“, or “schadenfreude,” apsychologists’ term for our collective desire to hear, and remember bad news. It isn’t just schadenfreude, they contend, but that peoples’ brains have evolved to react quickly to potential threats. Bad news could be a signal that they need to change what they’re doing to avoid danger.

Trussler and Soroka argue there’s some evidence that people respond quicker to negative words. In their experiments, they flashed the word “cancer”, “bomb” or “war” up at someone and they hit a button in response quicker than if that word is “baby”, “smile” or “fun” (despite these pleasant words being slightly more common). Participants were also able to recognize negative words faster than positive words, and even tell that a word is going to be unpleasant before they can tell exactly what the word is going to be.

There’s another interpretation that Trussler and Soroka advanced: people pay attention to bad news, because they think the world is better or more positive than it actually is. This pleasant view of the world makes bad news all the more surprising and salient. It is only against a light background that the dark spots are highlighted. So peoples’ attraction to bad news may be more complex than just journalistic cynicism or a hunger springing from the darkness within, Trussler and Soroka argued.

They argue that “negative network news content, in comparison with positive news content, tends to increase both arousal and attentiveness. In contrast, positive news content has an imperceptible impact on the physiological measures we focus on. Indeed, physiologically speaking, a positive news story is not very different from the gray screen we show participants between news stories.”

What about our personal lives?

Psychologist John Gottman at the University of Washington, found that there is kind of thermostat operating in healthy marriages that regulates the balance between positive and negative. He found that relationships run into serious problems when the negative to positive ratio becomes seriously imbalanced. If a couple is unable to maintain the 5:1 ratio of positivity to negativity conflict is likely to increase while relationship satisfaction will likely decrease.

He also found that the magic ratio is five positive to one negative.If you want to learn how to stay positive in a negative world you must expose yourself to as many positive experiences as you can while minimizing exposure to the negative, Gottman says.

Do you want the good news or the bad news first?

An opening like that will send a chill through your veins, no matter what the topic. It’s especially worrying when coming from a significant other or a doctor. And the statement is often followed by a question: Which do you want first, the good news or the bad news? A new study says that you probably want the bad news first. But it also finds that, if the decision is left to the news deliverer, you can’t always get what you want.

Psychologists Angela Legg and Kate Sweeny from the University of California, Riverside decided to answer this age-old question, and to see whether the person giving the news wanted to give the good news or the bad news first. Finally, they looked at how the order that the information is delivered might change how people feel about the news. Their results were published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

The scientists had 121 college students come into the lab in pairs. The researchers assigned each pair a news-giver and a news-recipient. The students did not know their partner beforehand. All students took a personality test designed to assess the Big Five personality dimensions: conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism and openness. A few minutes later, an experimenter came in and told the students that their tests were scored, and that there was both good news and bad news. For example, a student might have tested really high on leadership but turned out to look very selfish indeed.

In reality, the tests had not been scored, and the students wouldn’t end up getting the real good news or bad news. They just had to pick which one they wanted first. For the news-receivers, the experimenter asked which they would like to receive first, and why. Their only job was to receive news. For the news-givers, the experimenter told them they would have to deliver the results of a personality test, and news-givers were asked which they would like to give first, and why.

Using separate groups of students in a new test, the experimenters then actually gave people the results of their personality tests with good news or bad news first, and asked how worried they were as the test went on. They also tested whether telling the news-givers to think of the other person’s feelings altered the order which in they wanted to give the news.

And we really do like to get the bad news first. A whopping 78 percent of students tested said that they wanted the bad news first, thanks. This is consistent with previous studies, which also showed that people would rather get bad news first. But however much you want it, you might not get it: 54 to 68 percent of news-givers preferred to give good news first. When the news-givers were prompted to feel empathy for the receiver with statements like “put yourself in the receiver’s shoes,” the percentage who wanted to give the bad news first increased, but the effects weren’t very large (though they were statistically significant). You want the bad news first, but they don’t want to give it to you.

But does getting the bad news first make a difference Legg and Sweeney asked. To answer that question, they had a third group of students get either good news first or bad news first, and assessed how worried they were before and after they’d gotten the news. Both groups displayed increased worry, no matter what order the news came in. However, But it students who received the bad news first ended up less worried than those who received the good news first.

Legg and Sweeney, also wanted to determine if it made a difference if the person was the giver or receiver of the bad news and ifthe information will be used to modify behavior. They found if participants were on the receiving end, more than 75 percent of them wanted the bad news first. “If people know they are going to get bad news, they would rather get it over with,” Legg says. Then, if there is good news to follow, “you end on a high note.”

Conversely Legg and Sweeney found that news givers—65 and 70 percent—chose to give good news first, then the bad news. “When news givers go into a conversation, they are anxious. No one enjoys giving bad news. They don’t understand that having to wait for bad news makes the recipient more anxious.”

But good news first, then bad could be a useful strategy if the goal is to get someone to change a behavior—when, for example, Legg says, “you are giving feedback to a patient needing to lose weight, who has to take action. The recipient doesn’t feel good about the news, but may do something about it.”

The Sandwich Approach

Then there is what Legg calls the good news, bad news, good news sandwich—when the bad news comes between piece of good news on either side. Example: “Your cholesterol is down. By the way, your blood pressure is morbidly high. Your blood sugar levels are good.” That’s fine if you want someone to feel good, she says. “But hiding the bad news in the sandwich is generally not a good strategy. It downplays the bad news, and the recipient gets confused.”

The person who delivers a bad news sandwich is engaging in what Legg calls conversational acrobatics. “They believe they are making the conversation easier, but the message gets garbled.” There’s even an acronym in psychological jargon for people who delay giving out bad news or avoid it altogether—MUM (mum about undesirable messages). “The best news-giving strategies take into account that sometimes we want to make people feel good and sometimes we need them to act,” she says.

Legg’s advice to doctors is that when relaying a diagnosis or prognosis, it’s better to give the bad news first, and then the positive information to help the patient accept it. “Many physicians prefer not to have to give bad news until it’s obvious,” says Thomas J. Smith, director of palliative medicine at the Johns Hopkins Institutions in Baltimore.

According to one study Smith cites, “If we look at the charts of people with lung cancer, only 22 percent of the charts have any notation that the doctor and patient talked about the fact that the patient is going to die,” he says. ” Most of the time the conversation goes along the lines of ‘it’s incurable, but treatable.’ Many times it doesn’t get mentioned again.” Yet, Smith says that 90 percent of people say they want truthful and honest information, even if it’s negative.

The “bad news” conversation, Smith stresses, needs to be more than one conversation. “When you give a bad diagnosis, they don’t hear anything [anyone says] for the next three weeks anyway. They are stunned. ” The situation is improving according to Smith. “Forty years ago when I started, palliative care wasn’t the norm,” he says. Now, at Johns Hopkins, medical students practice breaking bad news to a trained actor “patient.” “Many [other] countries are changing, as well. Japan has shifted from no one being told to everyone being told” the truth, even if it’s bad news, he says.

In Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, Boston College psychologist, Elizabeth Kensinger and colleagues, explain when emotion is likely to reduce our memory inconsistencies. Her research shows that whether an event is pleasurable or aversive seems to be a critical determinant of the accuracy with which the event is remembered, with negative events being remembered in greater detail than positive ones.

For example, after seeing a man on a street holding a gun, people remember the gun vividly, but they forget the details of the street. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), studies have shown increased cellular activity in emotion-processing regions at the time that a negative event is experienced.

The more activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and the amygdala, two emotion-processing regions of the brain, the more likely an individual is to remember details intrinsically linked to the emotional aspect of the event, such as the exact appearance of the gun.

Kensinger argues that recognizing the effects of negative emotion on memory for detail may, at some point, save our lives by guiding our actions and allowing us to plan for similar future occurrences. “These benefits make sense within an evolutionary framework,” writes Kensinger. “It is logical that attention would be focused on potentially threatening information.”

This line of research has far-reaching implications in understanding autobiographical memory and assessing the validity of eyewitness testimony. Kensinger also believes that this research may provide insight into the symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Is there any good news in all this?

There will always be bad news somewhere in the world or in your own life, but understanding your natural bias toward negativity can help you to consciously direct your focus toward the encouraging, motivating and positive influences around you.

According to positive psychologists we can change our habits, and we can focus on the glass being half-full. When we acquire new habits, our brains acquire “mirror neurons” and develop a positive perspective that can spread to other people like a virus. This is not about being a Pollyanna or “goody-two-shoes,” is about being able to reprogram our brains. To apply this positive psychology and brain research knowledge to our attitudes and behaviors with relation to our current economic, social or environmental conditions, we can encourage our news deliverers to present a more balanced and multi-dimensional point of view. Giving us the bad news, so that our brains are hard-wired into a negative state, will just reinforce the negativity. You also might want to consider that the best thing you can do is watch and read less news, and search for more positive stories.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself and Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go,available in paperback and ebook on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.