By Ray Williams

May 3, 2021

Lying and deception are common human behaviors. Until relatively recently, there has been little actual research into just how often people lie.

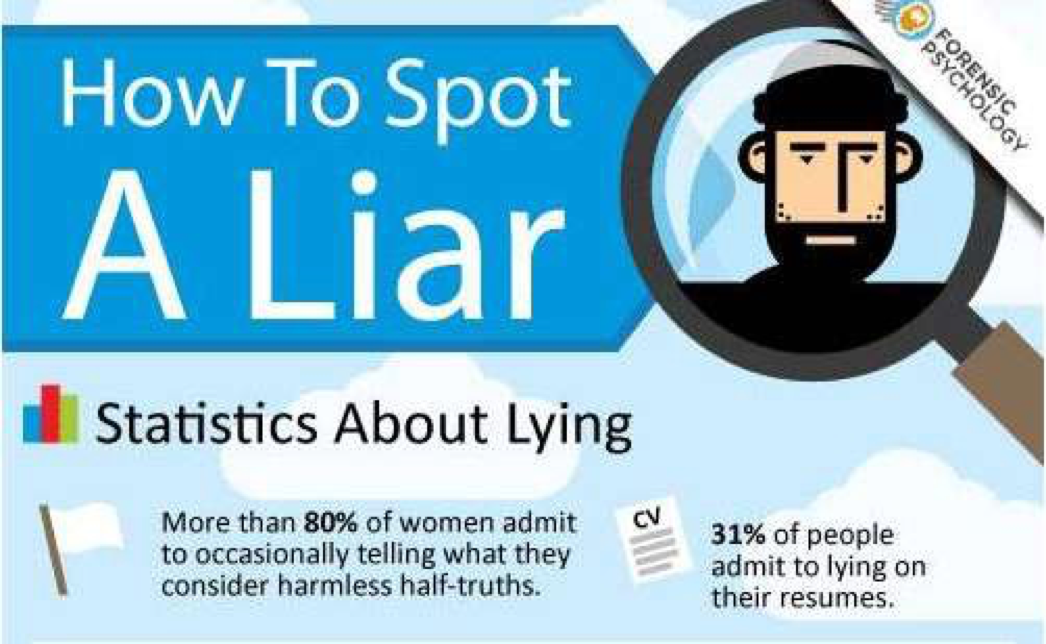

A 2004 Reader’s Digest poll found that as many as 96% of people admit to lying at least sometimes. Researchers also found that about half of all lies were told by just 5% of all the subjects. The study suggests that while prevalence rates may vary, there likely exists a small group of very prolific liars. The average person hears between 10 and 200 lies per day. Strangers lie to each other three times within the first 10 minutes of meeting, on average. College students lie to their mothers in one-fifth of all interactions.

Those little white lies are slipping out more often than you realize: One study found that Americans, on average, tell about 11 lies per week. Other research shows that number is on the conservative side. A study published in the Journal of Basic and Applied Social Psychology found that 60 percent of people can’t go 10 minutes without lying at least once. And it gets worse: Those that did lie actually told an average of three lies during that short conversation.

Why do we do it?

In surveying more than 100 psychology graduate students currently or previously in therapy, Leslie Martin, PhD, of Wake Forest University’s counseling center, found that of the 37 percent who reported lying, most did so “to protect themselves in some way — mostly to avoid shame or embarrassment, to avoid painful emotions and to avoid being judged,”and 60 percent of people can’t go 10 minutes without lying at least once.

A study published in the journal Nature Neuroscience found that lying is a slippery slope: When people tell small lies, the brain becomes desensitized to the pang of guilt that dishonesty usually causes. Basically, the more you lie, the easier it is to do it, and the bigger the lies get.

A large meta-analysis revealed overall accuracy of distinguishing truths from lies was just 53 percent — not much better than flipping a coin, note the authors, psychologists Charles Bond, PhD, of Texas Christian University, and Bella DePaulo, PhD, of the University of California, Santa Barbara.

The reality is that most people will probably lie from time to time. Some of these lies are little white lies intended to protect someone else’s feelings (“No, that skirt does not make you look fat!”). In other cases, these lies can be much more serious (like lying on a resume) or even sinister (covering up a crime).

More Lies Told on Email and Telephone Than in Person

It’s hard to look someone straight in the eye and tell them a blatant lie. Those who can are marked out for more nefarious occupations. Like politics. This is well-illustrated by a study published recently in the Journal of Applied Psychology which examines how much people lie in emails compared with good old pen and paper (Naquin et al., 2010). Lies increased 50%

In their first experiment 48 participants were told they had to split $89 between themselves and a partner who they hadn’t met. The trick was that the partner didn’t know the exact size of the pot, only that it was somewhere between $5 and $100. Participants then either sent an email or wrote a pen and paper note to their partner telling them the size of the pot and the allocation. Actually there was no blind partner, it was a test to see what participants would do in the two mediums. In the event, over email 24 out of 26 people lied about the pot’s size, while in a different group of 26 participants using pen and paper, only 14 lied. What’s important is the difference between the two conditions: that lying increased by 50% from pen and paper to email.

In some ways a more damning indictment of email from Naquin et al.’s study was that people reported feeling more justified in lying over email than they did when writing with pen and paper. Across a further two experiments people consistently lied more over email and felt more justified in doing so, even when they were lying to someone they knew and when that person would find out. Participants seemed relatively unconcerned about the damage to their reputation caused by lying over email.

What is it, then, about email that is so different from a handwritten message?

To understand this Naquin et al. call upon a theory first put forward by eminent social psychologist Albert Bandura. Called moral disengagement theory, it tries to predict how people release themselves from their normal ethical standards, whether it’s playing fair, respecting others or telling the truth. Two of these are (1) by changing how the offending actions are viewed and (2) by creating psychological distance from the harmful consequences of the action. Both of these are encouraged by three characteristics of email:

- Less permanent: people think of it as a substitute for conversation rather than a letter. People feel they are “chatting” more over email, rather than writing to each other. The impermanence of email is emphasized by a Gmail feature which allows users to ‘unsend’ a message within 5 seconds of sending.

- Less restrained: people behave in a more disinhibited way online. Online exchanges show less conformity to social norms, people display much less restraint and are less worried about what others think of them.

- Lower personal connection: studies show that online, people feel less trust and rapport with others, leaving them with a sense of disconnection.

All of these may lead people to feel low levels of accountability for their emails. Hence more fibs.

Examining online communications, Jeffrey Hancock at Cornell University found that liars on average wrote 28% more words than truth tellers and also used fewer self-oriented words, but that participants were unable to use this to work out when they were being deceived

Although email seems almost old-fashioned given that web years, like dog years, are so compressed, our culture is still adapting to what is an incredibly useful tool. Indeed some research has suggested that people lie less over email than they do face-to-face or over the telephone.

Some Necessary Definitions

A lie is an assertion that is believed to be false, typically used with the purpose of deceiving someone but it can also mean other things and have different characteristics. For example:

- A barefaced, bald-faced or bold-faced lie is an impudent, brazen, shameless, flagrant, or audacious lie that is sometimes but not always undisguised and that it is even then not always obvious to those hearing it.

- A big lie is one that attempts to trick the victim into believing something major, which will likely be contradicted by some information the victim already possesses, or by their common sense. When the lie is of sufficient magnitude it may succeed, due to the victim’s reluctance to believe that an untruth on such a grand scale would indeed be concocted.

- A black lie is about simple and callous selfishness. We tell black lies when others gain nothing and the sole purpose is either to get ourselves out of trouble (reducing harm against ourselves) or to gain something we desire (increasing benefits for ourselves). The worst black lies are very harmful for others. Perhaps the very worst gain us a little yet harm others a great deal.

- A blue lie is a form of lying that is told purportedly to benefit a collective or “in the name of the collective good”. The origin of the term “blue lie” is possibly from cases where police officers made false statements to protect the police force or to ensure the success of a legal case against an accused. This differs from the blue wall of silence in that a blue lie is not an omission but a stated falsehood.

- Bluffing is to pretend to have a capability or intention one does not possess. Bluffing is an act of deception that is rarely seen as immoral when it takes place in the context of a game, such as poker, where this kind of deception is consented to in advance by the players. For instance, gamblerswho deceive other players into thinking they have different cards to those they really hold, or athletes who hint that they will move left and then dodge right are not considered to be lying (also known as a feintor juke). In these situations, deception is acceptable and is commonly expected as a tactic.

- Bullshitting (also B.S., bullcrap, bull) does not necessarily have to be a complete fabrication. While a lie is related by a speaker who believes what is said is false, bullshit is offered by a speaker who does not care whether what is said is true because the speaker is more concerned with giving the hearer some impression. Thus bullshit may be either true or false, but demonstrates a lack of concern for the truth that is likely to lead to falsehoods

- A cover-up may be used to deny, defend, or obfuscate a lie, errors, embarrassing actions, or lifestyle, and/or lie(s) made previously. One may deny a lie made on a previous occasion, or alternatively, one may claim that a previous lie was not as egregious as it was. For example, to claim that a premeditated lie was really “only” an emergency lie, or to claim that a self-serving lie was really “only” a white lie or noble lie. This should not be confused with confirmation biasin which the deceiver is deceiving themselves.

- Defamation is the communication of a false statement that harms the reputation of an individual person, business, product, group, government, religion, or nation.

- To deflect is to avoid the subject that the lie is about, not giving attention to the lie. When attention is given to the subject the lie is based around, deflectors ignore or refuse to respond. Skillful deflectors are passive-aggressive, who when confronted with the subject choose to ignore and not respond.

- Disinformation is intentionally falseor misleading informationthat is spread in a calculated way to deceive target audiences.

- An exaggeration occurs when the most fundamental aspects of a statement are true, but only to a certain degree. It also is seen as “stretching the truth” or making something appear more powerful, meaningful, or real than it is. Saying that someone devoured most of something when they only ate half would be considered an exaggeration. An exaggeration might be easily found to be ahyperbole where a person’s statement (i.e. in informal speech, such as “He did this one million times already!”) is meant not to be understood literally.

- Fake news is supposed to be a type of yellow journalism that consists of deliberate misinformation, conspiracies or hoaxes spread via traditional print and broadcast news media or online social media. Sometimes the term is applied as a deceptive device to deflect attention from uncomfortable truths and facts, however.

- A fib is a lie that is easy to forgive due to its subject being a trivial matter; for example, a child may tell a fib by claiming that the family dog broke a household vase, when the child was the one who broke it.

- Fraud refers to the act of inducing another person or people to believe a lie in order to secure material or financial gain for the liar. Depending on the context, fraud may subject the liar to civil or criminal penalties.

- A gray lie is told partly to help others and partly to help ourselves. It may vary in the shade of gray, depending on the balance of help and harm. Gray lies are, almost by definition, hard to clarify. For example, you can lie to help a friend out of trouble but then gain the reciprocal benefit of them lying for you while those they have harmed in some way lose out.

- A half-truth is a deceptive statement that includes some element of truth. The statement might be partly true, the statement may be totally true, but only part of the whole truth, or it may employ some deceptive element, such as improper punctuation or double meaning, especially if the intent is to deceive, evade, blame, or misrepresent the truth.

- An honest lie (or confabulation) may be identified by verbal statements or actions that inaccurately describe the history, background, and present situations. There is generally no intent to misinform and the individual is unaware that their information is false. Because of this, it is not technically a lie at all since, by definition, there must be an intent to deceive for the statement to be considered a lie. Some would say this is a contradiction.

- Jocose lies are lies meant in jest, intended to be understood as such by all present parties. Teasing and irony are examples. A more elaborate instance is seen in some storytelling traditions, where the storyteller’s insistence that the story is the absolute truth, despite all evidence to the contrary (i.e., tall tale), is considered humorous. There is debate about whether these are “real” lies, and different philosophers hold different views. The Crick Crack Club in London arranges a yearly “Grand Lying Contest” with the winner being awarded the coveted “Hodja Cup” (named for the Mulla Nasredd in: “The truth is something I have never spoken.”). In the United States, the Burlington Liars’ Club awards an annual title to the “World Champion Liar.”

- Lying by omission, also known as a continuing misrepresentation or quote mining, occurs when an important fact is left out in order to foster a misconception. Lying by omission includes the failure to correct pre-existing misconceptions. For example, when the seller of a car declares it has been serviced regularly, but does not mention that a fault was reported during the last service, the seller lies by omission. It may be compared to dissimulation. An omission is when a person tells most of the truth, but leaves out a few key facts that therefore, completely obscures the truth.

- Lying in trade occurs when the seller of a product or service may advertise untrue facts about the product or service in order to gain sales, especially by competitive advantage. Many countries and states have enacted consumer protection laws intended to combat such fraud.

- A memory hole is a mechanism for the alteration or disappearance of inconvenient or embarrassing documents, photographs, transcripts, or other records, such as from a website or other archive, particularly as part of an attempt to give the impression that something never happened. Fears currently exist that the Trump administration may be guilty of this.

- A noble lie, which also could be called a strategic untruth, is one that normally would cause discord if uncovered, but offers some benefit to the liar and assists in an orderly society, therefore, potentially being beneficial to others. It is often told to maintain law, order, and safety.

- In psychiatry, pathological lying (also called compulsive lying, pseudologia fantastica, and mythomania) is a behavior of habitual or compulsive lying. It was first described in the medical literature in 1891 by Anton Delbrueck. Although it is a controversial topic, pathological lying has been defined as “falsification entirely disproportionate to any discernible end in view, may be extensive and very complicated, and may manifest over a period of years or even a lifetime”. The individual may be aware they are lying, or may believe they are telling the truth, being unaware that they are relating fantasies.

- Perjury is the act of lying or making verifiably false statements on a material matter under oath or affirmation in a court of law, or in any of various sworn statements in writing. Perjury is a crime, because the witness has sworn to tell the truth and, for the credibility of the court to remain intact, witness testimony must be relied on as truthful.

- Puffery is an exaggerated claim typically found in advertising and publicity announcements, such as “the highest quality at the lowest price”, or “always votes in the best interest of all the people”. Such statements are unlikely to be true — but cannot be proven false and so, do not violate trade laws, especially as the consumer is expected to be able to determine that it is not the absolute truth.

- The phrase “speaking with a forked tongue” means to deliberately say one thing and mean another or, to be hypocritical, or act in a duplicitous manner. This phrase was adopted by Americans around the time of the Revolution, and may be found in abundant references from the early nineteenth century — often reporting on American officers who sought to convince the Indigenous peoples of the Americas with whom they negotiated that they “spoke with a straight and not with a forked tongue” (as for example, President Andrew Jackson told members of the Creek Nation in 1829). According to one 1859 account, the proverb that the “white man spoke with a forked tongue” originated in the 1690s, in the descriptions by the indigenous peoples of French colonials in America inviting members of the Iroquois Confederacy to attend a peace conference, but when the Iroquois arrived, the French had set an ambush and proceeded to slaughter and capture the Iroquois.

- Weasel word is an informal termfor words and phrases aimed at creating an impression that a specific or meaningful statement has been made, when in fact only a vague or ambiguous claim has been communicated, enabling the specific meaning to be denied if the statement is challenged. A more formal term is equivocation.

- A white lie is a harmless or trivial lie, especially one told in order to be polite or to avoid hurting someone’s feelings or stopping them from being upset by the truth. A white lie also is considered a lie to be used for greater good (pro-social behavior). It sometimes is used to shield someone from a hurtful or emotionally-damaging truth, especially when not knowing the truth is deemed by the liar as completely harmless.

Cultural References

Throughout western history, writers, philosophers and the media have pined on the issue of honesty and lies:

Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio was a wooden puppet often led into trouble by his propensity to lie. His nose grew with every lie; hence, long noses have become a caricature of liars. The Boy Who Cried Wolf, a fable attributed to Aesop about a boy who continually lies that a wolf is coming. When a wolf does appear, nobody believes him anymore.

A famous anecdote by Parson Weems claims that George Washington once cut at a cherry tree with a hatchet when he was a small child. His father asked him who cut the cherry tree and Washington confessed his crime with the words: “I’m sorry, father, I cannot tell a lie.”

To Tell the Truth was the originator of a genre of game shows with three contestants claiming to be a person only one of them is.

Glenn Kessler, a journalist at The Washington Post, awards one to four Pinocchios to politicians in his Washington Post Fact Checker blog.

The cliché “All is fair in love and war”, asserts justification for lies used to gain advantage in these situations. Sun Tzu declared that “All warfare is based on deception.” Machiavelli advised in The Prince that a prince must hide his behaviors and become a “great liar and deceiver”, and Thomas Hobbes wrote in Leviathan: “In war, force and fraud are the two cardinal virtues.”

The concept of a memory hole was first popularized by George Orwell’s dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four, where the Party’s Ministry of Truth systematically re-created all potential historical documents, in effect re-writing all of history to match the often-changing state propaganda. These changes were complete and undetectable.

In the film Big Fat Liar, the story producer Marty Wolf (a notorious and proud liar) steals a story from student Jason Shepard, telling of a character whose lies become out of control to the point where each lie he tells causes him to grow in size.

In the film Liar Liar, the lawyer Fletcher Reede (Jim Carrey) cannot lie for 24 hours, due to a wish of his son that magically came true.

In the 1985 film Max Headroom, the title character comments that one can always tell when a politician lies because “their lips move”. The joke has been widely repeated and rephrased.

Larry-Boy! And the Fib from Outer Space! was a Veggie Tales story of a crime-fighting super-hero with super-suction ears, having to stop an alien, calling himself “Fib”, from destroying the town of Bumblyburg due to the lies that caused Fib to grow. Telling the truth is the moral to this story.

Lie to Me is a television series based on behavior analysts who read lies through facial expressions and body language. The protagonists, Dr. Cal Lightman and Dr. Gillian Foster are based on the above-mentioned Dr. Paul Ekman and Dr. Maureen O’Sullivan.

The Invention of Lying is a 2009 movie depicting the fictitious invention of the first lie, starring Ricky Gervais, Jennifer Garner, Rob Lowe, and Tina Fey.

The Adventures of Baron Munchausen tell the story about an eighteenth-century baron who tells outrageous, unbelievable stories, all of which he claims are true.

In the games Grand Theft Auto IV and Grand Theft Auto V, there’s an agency named FIB, a parody of the FBI, which is known to cover up stories, cooperate with criminals, and extract information with the use of lying.

Why Do People Lie?

The Ethics of Lying

Aristotle believed no general rule on lying was possible, because anyone who advocated lying could never be believed, he said. Although the philosophers, St. Augustine, St. Thomas Aquinas, and Immanuel Kant, condemned all lying, Thomas Aquinas did advance an argument for lying, however. According to all three, there are no circumstances in which, ethically, one may lie. Even if the onlyway to protect oneself is to lie, it is never ethically permissible to lie even in the face of murder, torture, or any other hardship. Each of these philosophers gave several arguments for the ethical basis against lying, all compatible with each other. Among the more important arguments are:

- Lying is a perversion of the natural faculty of speech, the natural end of which is to communicate the thoughts of the speaker.

- When one lies, one undermines trust in society.

Meanwhile, utilitarian philosophers have supported lies that achieve good outcomes — white lies. In his 2008 book, How to Make Good Decisions and Be Right All the Time, Iain King suggested a credible rule on lying was possible, and he defined it as: “Deceive only if you can change behavior in a way worth more than the trust you would lose, were the deception discovered (whether the deception actually is exposed or not).”

In the book Lying, neuroscientist Sam Harris argues that lying is negative for the liar and the person who’s being lied to. To say lies is to deny others access to reality, and often we cannot anticipate how harmful lies can be. The ones we lie to may fail to solve problems they could have solved only on a basis of good information. To lie also harms oneself, makes the liar distrust the person who’s being lied to. Liars generally feel badly about their lies and sense a loss of sincerity, authenticity, and integrity. Harris asserts that honesty allows one to have deeper relationships and to bring all dysfunction in one’s life to the surface.

In his famous treatise, Human, All Too Human, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche suggested that those who refrain from lying may do so only because of the difficulty involved in maintaining lies. This is consistent with his general philosophy that divides (or ranks) people according to strength and ability; thus, some people tell the truth only out of weakness.

The Consequences of Lying

The potential consequences of lying are manifold; some in particular are worth considering. Typically lies aim to deceive, when deception is successful, the hearer ends up acquiring a false belief (or at least something that the speaker believes to be false). When deception is unsuccessful, a lie may be discovered. The discovery of a lie may discredit other statements by the same speaker, staining his reputation. In some circumstances, it may also negatively affect the social or legal standing of the speaker. Lying in a court of law, for instance, is a criminal offense (perjury).

Both Hannah Arendt and George Orwell spoke about extraordinary cases in which an entire society is being lied to consistently. She said that the consequences of such lying are “not that you believe the lies, but rather that nobody believes anything any longer. This is because lies, by their very nature, have to be changed, and a lying government has constantly to rewrite its own history. On the receiving end you get not only one lie — a lie which you could go on for the rest of your days — but you get a great number of lies, depending on how the political wind blows.”And of course, we’ve witnessed how a large percentage of the American public have been lied to by GOP politicians (including former President Trump) by falsely claiming that Trump had won the election and Joe Biden had illegally stolen it.

The Psychology of Lying

It is asserted by some scholars that the capacity to lie is a talent human beings possess universally.

The evolutionary theory proposed by Darwin states that only the fittest will survive and by lying, we aim to improve other’s perception of our social image and status, capability, and desirability in general. Studies have shown that humans begin lying at a mere age of six months, through crying and laughing, to gain attention.

Scientific studies have shown differences in forms of lying across gender. Although men and women lie at equal frequencies, men are more likely to lie in order to please themselves while women are more likely to lie to please others. The presumption is that humans are individuals living in a world of competition and strict social norms, where they are able to use lies and deception to enhance chances of survival and reproduction.

Stereotypically speaking, researchers assert that men like to exaggerate about their sexual expertise, but shy away from topics that degrade them while women understate their sexual expertise to make themselves more respectable and loyal in the eyes of men and avoid being labelled as a “scarlet woman”.

Those with Parkinson’s disease show difficulties in deceiving others, difficulties that link to prefrontal hypometabolism. This suggests a link between the capacity for dishonesty and integrity of prefrontal functioning.

Pseudologia fantastica is a term applied by psychiatrists to the behavior of habitual or compulsive lying. Mythomania is the condition where there is an excessive or abnormal propensity for lying and exaggerating.

A recent study found that composing a lie takes longer than telling the truth. Or, as First Nations Chief Joseph succinctly put it, “It does not require many words to speak the truth.”

Lying and Self-Esteem

A study, published in the Journal of Basic and Applied Psychology, found that 60 percent of people had lied at least once during the 10-minute conversation, saying an average of 2.92 inaccurate things.

“People almost lie reflexively,” author of the study Robert Feldman says. “They don’t think about it as part of their normal social discourse.” But it is, the research showed.

“We’re trying not so much to impress other people but to maintain a view of ourselves that is consistent with the way they would like us to be,” Feldman said. We want to be agreeable, to make the social situation smoother or easier, and to avoid insulting others through disagreement or discord.

Workplace lies

Other research has delved into prevarication in the workplace.

Self-esteem and threats to our sense of self are also drivers when it comes to lying to co-workers, rather than strangers, says Jennifer Argo of the University of Alberta.

A recent study she co-authored showed that people are even more willing to lie to coworkers than they are to strangers.

“We want to both look good when we are in the company of others (especially people we care about), and we want to protect our self-worth,” Argo told LiveScience.

The experiment involved reading a scenario to a subject, telling them they had paid more than a coworker for the same new car. When the coworker, in the scenario, mentioned what they had paid, $200 or $2,000 more in different versions of the experiment, the subject was asked to report how they would respond.

Argo found that her subjects were more willing to lie when the price difference was small and when they were talking to a coworker rather than to a stranger.

Consumers lie to protect their public and private selves, she wrote in the Journal of Consumer Research with her colleagues from the University of Calgary and University of British Columbia.

Argo said she was surprised that people are so willing to lie to someone they know even over a small price discrepancy.

“I guess closely tied to this is that people appear to be short-term focused when they decide to deceive someone — save my self-image and self-worth now, but later on if the deceived individual finds out it can have long-term consequences,” she said.

Feldman says people should become more aware of the extent to which we tend to lie and that honesty yields more genuine relationships and trust. “The default ought to be to be honest and accurate … We’re better off if honesty is the norm. It’s like the old saying: honesty is the best policy.”

The Gut Connection

Lying really gets the juice flowing, according to a new study that suggests changes in gastric physiology perform better than standard polygraph methods in distinguishing between lying and telling the truth.

The upshot: mental stress does indeed affect your stomach.

The University of Texas study, announced yesterday at a meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology, shows a clear link between the act of lying and a significant increase in gastric arrhythmia, researchers said.

They tested 16 volunteers using electrogastrogram (EGG) and electrocardiogram (EKG) recordings.

Both lying and truth telling affected cardiac symptoms, while lying was also associated with gastric symptoms. The EGG showed a significant decrease in the percentage of normal gastric “slow waves” when the subject was lying that corresponded to a significant increase in the average heart rate during the same situation, the scientists report.

“We concluded that the addition of the EGG to standard polygraph methods has clear value in improving the accuracy of current lie detectors,” said study leader Pankaj Pasricha. “The communication between the big brain and the little brain in the stomach can be complex and merits further study.”

Lying Can Be Hard to Detect

According to Pamela Meyer, author of the book Liespotting and presenter of a TED Talk with more than 16 million views, if we’re being lied to that often, how can we do a better job of catching the prevaricators we interact with?

People are surprisingly bad at detecting lies. One study, for example, found that people were only able to accurately detect lying 54% of the time in a lab setting — hardly impressive when factoring in a 50% detection rate by pure chance alone.

Clearly, behavioral differences between honest and lying individuals are difficult to discriminate and measure. Researchers have attempted to uncover different ways of detecting lies and found there may not be a simple, tell-tale sign that someone is dishonest (like Pinocchio’s nose).

The Famous Polygraph Lie Detector

Are Polygraphs (Lie Detector Machine)Tests Accurate?

A polygraph is not a lie detector, as LiveScience’s Bad Medicine Columnist Christopher Wanjek has explained. A polygraph detects physiological expressions associated with lying in some people, such as a racing heart and sweaty fingers. The determination of truth vs. falsehood is subjective, and polygraph examiners are often wrong.

Doug Williams might be the world’s loudest critic of the polygraph machine. A former cop who now refers to himself as a “crusader,” he sells manuals that teach people the ins and outs of the test for $15.57.

“It is time to put to a stop this government sponsored sadism perpetrated by those who use this insidious Orwellian instrument of torture called the lie detector!” the author writes on his site, which also explains his life goal of proving the test is “bullshit” that ruins lives and careers. He doesn’t talk about cheating the test, but, instead, passing it. Ostensibly, his goal is keep innocent people from incriminating themselves.

Lie detectors have been under fire since they were invented in the early 1920s. The same year that the polygraph hit the scene in 1921, a 19-year-old named James Frye was arrested for the murder of a physician. The Washington, DC resident was given a crude blood pressure exam that supposedly proved his innocence, but a judge prevented the test administrator from testifying in court. Many states still adhere to the so-called Frye Standard, which says scientific evidence can’t be admitted in court unless its gained “general acceptance” in the research community.

That still hasn’t happened for the lie detector test. Len Saxe, a researcher at Brandeis University who put together a report on the polygraph for Congress in 2003, says the test is still pseudoscience. Most often it’s used by law enforcement to coerce confessions. If someone claims to be a polygraph expert and sits a suspect down to take a test, maybe one out of 20 times, the interviewee will decide not to even bother trying. But the test doesn’t work the way it’s supposed to, and the idea that an increased heart rate proves a subject is lying is a long-propagated myth.

“There’s no such thing as Pinocchio,” Saxe says. “But there is a thing called stage fright or being concerned when getting questioned about something that could lead to your arrest.”

The scientific community largely agrees. Psychology Today published a skeptical take on the lie detector test that read in part, “The lie detector can be considered a modern variant of the old technique of trial by ordeal. A suspected witch was thrown into a raging river on the premise that if she floated she was harnessing demonic powers.”

Although private-sector employers haven’t been able to give polygraphs to applicants since 1988, federal judges have discretion in whether or not to admit lie detector results as evidence. People convicted of sex crimes are continually required to take them to make sure they haven’t re-offended. And what’s almost scarier is that while a lie detector can produce a false negative, the opposite can happen as well.

Research on How to Tell if Someone is Lying

One of the most common misconceptions is the belief in universal signs of deception — consistent, reliable indicators that a person is lying. There are some signs that appear more frequently among liars than truth tellers; however, there has been no universal sign of lying identified. This is because not all liars demonstrate the same behaviors. One liar may decrease eye contact, while a second person may increase eye contact in response to the same question.

This is complicated by the fact that the same person can respond differently in the same situation — interpersonal differences — and also in different contexts — intrapersonal differences.

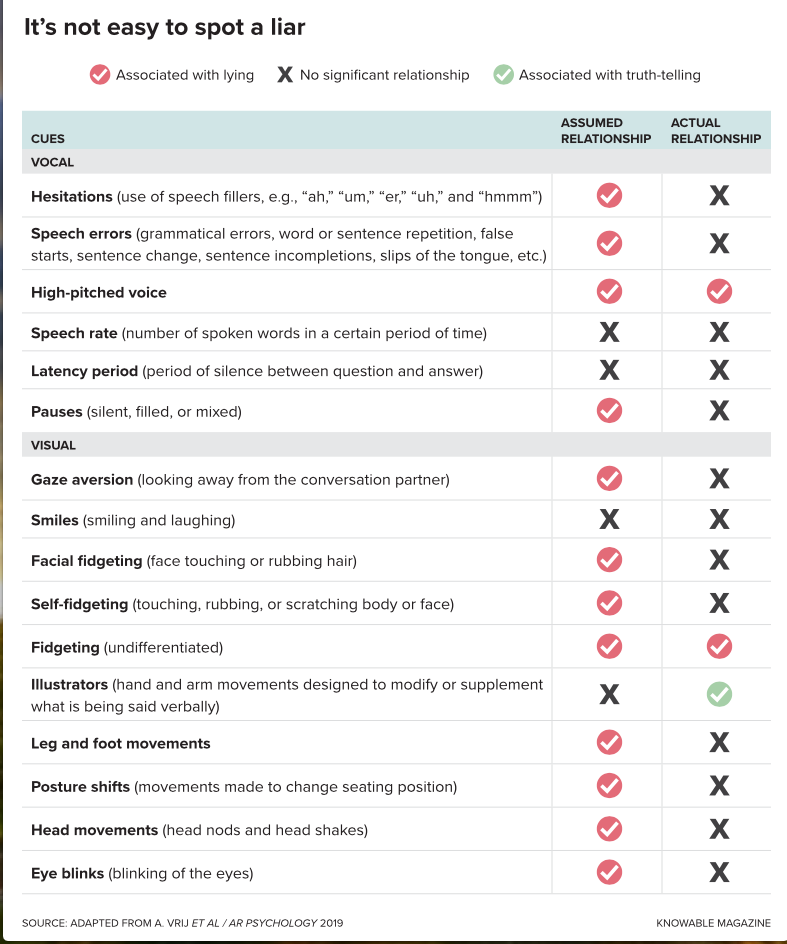

Across cultures, people believe that behaviors such as averted gaze, fidgeting and stuttering betray deceivers.

In fact, researchers have found little evidence to support this belief despite decades of searching. “One of the problems we face as scholars of lying is that everybody thinks they know how lying works,” says Hartwig, who coauthored a study of nonverbal cues to lying in the Annual Review of Psychology. Such overconfidence has led to serious miscarriages of justice, as Tankleff and Deskovic know all too well. “The mistakes of lie detection are costly to society and people victimized by misjudgments,” says Hartwig. “The stakes are really high.”It is likely that anyone who interviews criminals for a living will be lied to on a regular basis. In a study involving 509 people from a variety of career fields and agencies, only the U.S. Secret Service agents performed better than chance (50 percent). A number of other studies have provided similar results.

Another myth is the belief that only guilty people appear nervous. This idea assumes that a person who has nothing to hide has no reason to be nervous or to demonstrate fidgeting and anxiety often associated with deceit.

Psychologists have long known how hard it is to spot a liar. In 2003, psychologist Bella DePaulo, now affiliated with the University of California, Santa Barbara, and her colleagues combed through the scientific literature, gathering 116 experiments that compared people’s behavior when lying and when telling the truth. The studies assessed 102 possible nonverbal cues, including averted gaze, blinking, talking louder (a nonverbal cue because it does not depend on the words used), shrugging, shifting posture and movements of the head, hands, arms or legs. None proved reliable indicators of a liar, though a few were weakly correlated, such as dilated pupils and a tiny increase — undetectable to the human ear — in the pitch of the voice.

Three years later, DePaulo and psychologist Charles Bond of Texas Christian University reviewed 206 studies involving 24,483 observers judging the veracity of 6,651 communications by 4,435 individuals. Neither law enforcement experts nor student volunteers were able to pick true from false statements better than 54 percent of the time — just slightly above chance. In individual experiments, accuracy ranged from 31 to 73 percent, with the smaller studies varying more widely. “The impact of luck is apparent in small studies,” Bond says. “In studies of sufficient size, luck evens out.”

This size effect suggests that the greater accuracy reported in some of the experiments may just boil down to chance, says psychologist and applied data analyst Timothy Luke at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. “If we haven’t found large effects by now,” he says, “it’s probably because they don’t exist.”Psychologists have utilized research on body language and deception to help members of law enforcement distinguish between the truth and lies. Researchers at UCLA conducted studies on the subject in addition to analyzing 60 studies on deception in order to develop recommendations and training for law enforcement. Some of the results of their research were published in the American Journal of Forensic Psychiatry.

The research by Dr. Leanne ten Brinke, a forensic psychologist at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley, and her collaborators, suggests that our instincts for judging liars are actually fairly strong — but our conscious minds sometimes fail us.

Leanne ten Brinke and her colleagues have also published a study in Psychological Science in which they conclude that conscious awareness may hinder our ability to detect whether someone is lying, perhaps because we tend to seek out behaviors that are supposedly stereotypical of liars, like averted eyes or fidgeting. But those behaviors may not be all that indicative of an untrustworthy person.

“Our research was prompted by the puzzling but consistent finding that humans are very poor lie detectors, performing at only about 54 percent accuracy in traditional lie detection tasks,” explains ten Brinke. That’s hardly better than if participants simply guessed whether a person was lying. And it’s a finding that seems at odds with the fact that humans are typically quite sensitive to how others are feeling, what they’re thinking, and what their personalities are like.

The authors concluded that seemingly paradoxical findings may be accounted for by unconscious processes: “We set out to test whether the unconscious mind could catch a liar — even when the conscious mind failed,” she says. The results of their study showed that participants were more likely to unconsciously associate deception-related words (untruthful, dishonest, deceitful) with suspects who were actually lying. At the same time, participants were more likely to associate truthful words (honest, valid) with suspects who were actually telling the truth.

A second experiment confirmed these findings, providing evidence that people may indeed have some intuitive sense, outside of our conscious awareness, that detects when someone is lying. “These results provide a new lens through which to examine social perception, and suggest that — at least in terms of detection of lies — unconscious measures may provide additional insight into interpersonal accuracy,” according to ten Brinke.

Another study, conducted by ten Brinke and Stephen Porter of the University of British Columbia, analyzed films of liars and truth tellers from high-profile press conferences in which people appealed for missing relatives or claimed to have been the victims of crimes. “Our previous research with these films suggests that there are significant differences in the behavior of liars and truth tellers,” ten Brinke noted. “However, the alleged telltale pattern of eye movements failed to emerge.”

The results of their study showed that participants were more likely to unconsciously associate deception-related words (e.g. “untruthful,” dishonest,” and “deceitful”) with the suspects who were actually lying. At the same time, participants were more likely to associate truthful words (e.g. “honest” or “valid”) with the suspects who were actually telling the truth. A second experiment confirmed these findings, providing evidence that people may have some intuitive sense, outside of conscious awareness, that detects when someone is lying.

Dr. Lillian Glass, behavioral analyst, body language expert, and The Body Language of Liars author, said when trying to figure out if someone is lying, you first need to understand how the person normally acts. Certain habits, like pointing or over-sharing, might be perfectly within character for an individual.

In a study published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Aldert Vrij of the University of Portsmouth, Anders Granhag ofthe University of Gothenburg, and Stephen Porter of the University of British Columbia suggest verbalmethods of deception detection are more useful than nonverbal methods commonly believed to be effective, and that there are psychological differences between liars and truth-tellers that can be exploited in the search for the truth.

Trapping a liar is not always easy, the authors argue. Lies are often embedded in truths and the behavioral differences between liars and truth-tellers are usually very small. In addition, some people are just very good at lying. Lie detectors routinely make the common mistakes of overemphasizing nonverbal cues, neglecting intrapersonal variations (i.e., how a person acts when they are telling the truth versus when they are lying), and being overly confident in their lie-detection skills.

This research has important implications in a variety of settings, the authors write, including the courtroom, police interviews, and screening and identifying individuals with criminal intent — such as potential terrorists.

Former CIA officers Philip Houston, Michael Floyd, and Susan Carnicero distilled their professional deception-detecting skills into a fascinating book, Spy the Lie, also reveal how to tell if someone is lying.

In a comprehensive review of the literature on lying, published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Aldert Vrij (University of Portsmouth) and colleagues give an example of this. Participants in one study were supposed to detect lies in a statement from a convicted murder. The more visual cues the participants reported, the worse their ability to distinguish between truths and lies. Those who mentioned nonverbal behaviors, like gaze aversion or fidgeting, as “tells” for lying had the lowest accuracy at spotting lies. Instead, the study showed that listening carefully to what was being said was the best way to accurately discern the truth from a lie.

To find out more about verbal “tells” for lying, a team of researchers led by Judee Burgoon of the University of Arizona analyzed the speech of corporate fraudsters. Burgoon and colleagues analyzed over 1,000 statements made by the CEO and CFO of one company during six quarterly earnings conference calls. These two company executives were eventually convicted of fraud in multiple securities class action lawsuits.

The corporate earnings conference calls allowed the researchers to accurately compare lying during both scripted, as well as unscripted, speech. These calls are publicly broadcast, and follow a typical pattern; executives give an hour-long presentation on the company’s earnings, followed by an unscripted Q&A with financial analysts.

The research team hypothesized that lying would be more cognitive taxing than telling the truth. Compared to making a truthful statement, it might be easier to use simpler language during a lie.

“Because of the increased cognitive load and the human mind’s finite processing capacity, liars will have difficulty simultaneously maintaining a false story and producing linguistically complex utterances,” Burgoon and colleagues write. “In other words, the more difficult it is for deceivers to concoct a believable response, the more they must resort to simpler language.”

Previous experiments indicate that liars enlist specific strategies to try to distance themselves from their lies. They try to keep statements short and use vague or hedging language (e.g., “I guess” and “maybe” or “could,” “might”). Liars also tend to avoid first-person singular pronouns (e.g., “I,” “me,” “myself”), which are usually a clear signal that the speaker is taking ownership of a statement.

Using special software, the researchers analyzed sound recordings from these calls at a granular level. In order to differentiate between lies and true statements in the recordings, a financial expert was recruited to code the overstatements and lies related to financial fraud.

The analysis confirmed that there were certain speech patterns the executives fell into while lying. Fraud-related speech tended to be more “fuzzy” than non-fraudulent statements; the executives used more hedge words, more distancing language, and more uncertain statements.

Contrary to their expectations, the researchers also found that fraudulent statements tended to be longer and more detailed than honest ones.

Executives also used more positive and fewer negative emotional words during fraudulent statements, “suggesting a desire to put a positive spin on what was being reported.”

The researchers caution that the results of this study are limited because this study was based on only two people from one company. However, as different types of data become increasingly available — including call transcripts, online chat logs, social media — researchers will have a bigger pool of materials to draw from.

“For better or worse, new frauds are exposed on a regular basis leading to an expansion of available data. As additional candidate scenarios and features become available, richer analysis is possible,” the researchers conclude.

Has technology advanced sufficiently to assist in the detection of lies? Yes, according to a study by Ifeoma Nwogu, a research assistant professor at the University of Buffalo’s Center for Unified Biometrics and Sensors (CUBS); colleagues Nisha Bhaskaran and Venu Govindaraju; and University of Buffalo communications professor Mark G. Frank, who presented their findings at the IEEE Conference on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition.

In their study of 40 videotaped conversations, an automated system analyzing eye movements correctly identified whether subjects were lying or telling the truth 82.5 percent of the time. That’s a better accuracy rate than expert human interrogators typically achieve in lie-detection judgment experiments. (Experienced interrogators average closer to 65 percent.) “What we wanted to understand,” Nwogu said, “was whether there are signal changes emitted by people when they are lying, and can machines detect them?”

In the past, attempts to automate deceit detection have used systems that analyze changes in body heat or examine a slew of involuntary facial expressions. The automated system used by Nwogu’s team tracked a different trait — eye movement — and employed a statistical technique to model how people moved their eyes in two distinct situations: during regular conversation, and while fielding a question designed to prompt a lie.

People whose pattern of eye movements changed between the first and second scenario were assumed to be lying, while those who maintained consistent eye movement were assumed to be telling the truth. In other words, when the critical question was asked, a strong deviation from normal eye movement patterns suggested a lie. Previous experiments in which human judges coded facial movements found documentable differences in eye contact at times when subjects told a high-stakes lie.

Guilty? The length of your answer may give it away.

Researchers have developed a new approach to spot liars based on interviewing technique and psychological manipulation, with results published in the Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. The technique is part of a new generation of cognitive-based lie-detection methods that are beingincreasingly researched and developed.

One such approach is the Asymmetric Information Management (AIM) technique. At its core, it is designed to provide suspects with a clear means to demonstrate their innocence or guilt to investigators by providing detailed information. Small details are the lifeblood of forensic investigations and can provide investigators with facts to check and witnesses to question. Importantly, longer, more detailed statements typically contain more clues to a deception than short statements.

Essentially, the AIM method involves informing suspects of these facts. Specifically, interviewers make it clear to interviewees that if they provide longer, more detailed statements about the event of interest, then the investigator will be better able to detect if they are telling the truth or lying. For truth-tellers, this is good news. For liars, this is less good news.

Indeed, research shows that when suspects are provided with these instructions, they behave differently depending on whether they are telling the truth or not. Truth-tellers typically seek to demonstrate their innocence and commonly provide more detailed information in response to such instructions.

In contrast, liars wish to conceal their guilt. This means they are more likely to strategically withhold information in response to the AIM instructions. Their (totally correct) assumption here is that providing more information will make it easier for the investigator to detect their lie, so instead, they provide less information.

This asymmetry in responses from liars and truth-tellers — from which the AIM technique derives its name — suggests two conclusions. When using the AIM instructions, if the investigator is presented with a potential suspect who is providing lots of detailed information, they are likely to be telling the truth. In contrast, if the potential suspect is lying then the investigator would typically be presented with shorter statements.

Participants in an experiment were interviewed, and the AIM technique was used in half of the cases. We found that when the AIM technique was used, it was easier for the interviewer to spot liars. In fact, lie-detection accuracy rates increased from 48% (no AIM) to 81% — with truth-tellers providing more information. Research is also exploring methods for enhancing the AIM technique using cues which may support truth-tellers to provide even more information. Recalling information can be difficult, and truth-tellers often struggle with their recall.

Another recent study found that although liars can reduce telltale facial actions when under scrutiny, they can’t suppress them all, and micro expressions in the face may indicate a person is being deceptive. The study by Mark Frank and Carolyn Hurley, which was published in the Journal of Nonverbal Behavior examined whether subjects couldsuppress facial actions like eyebrow movements or smiles on command while under scrutiny by a liecatcher. It turns out that the subjects could, to a degree, but not completely and not always.

The results were derived from frame-by-frame coding of facial movements filmed during interrogations in which participants — some lying and some telling the truth — were asked to suppress specific parts of facial expressions. Hurley and Frank found that these actions could be reduced, but not eliminated, and that instructions to subjects to suppress one element of expression resulted in reduction of all facial movement, regardless of their implications for veracity. “Behavioral countermeasures,” according to Frank, “are the strategies engaged by liars to deliberately control face or body behavior to fool lie catchers.” Until this study, research had not shown whether or not liars could suppress elements of their facial expression as a countermeasure. “As a security strategy,” he says, “there is great significance in observing and interpreting nonverbal behavior during an investigative interview, especially when the interviewee is trying to suppress certain expressions.

“Although these facial movements are not necessarily guaranteed signs of deception,” says Frank, “expression suppression — regardless of its validity as a clue to deception — is clearly one of the more popular strategies used by liars to fool others. What we didn’t know was how well individuals can do this when they are lying or when they are telling the truth. “We correctly predicted that in interrogations in which deception is a possibility, individuals would be able to significantly reduce their rate and intensity of smiling and brow movements when requested to do so, but would be able to do so to a lesser degree when telling a lie. And since the lower face (and smile in particular) is easier to control than the upper face, we predicted that our subjects would more greatly reduce their rate of smiling, compared to their rate of brow movement, when requested to suppress these actions,” he says. “That turned out to be the case as well. We can reduce facial movements when trying to suppress them but we can’t eliminate them completely.”

Key linguistic cues can help reveal dishonesty as well, whether it’s a deliberate omission of information, or a complete lie, according to research by Lyn M. Van Swol, Michael T. Braun of the University of Wisconsin and Deepak Malhotra of Harvard University, published in the journal Discourse Processes.”Most people admit to having lied in negotiations, and everyone believes they’ve been lied to in these contexts,” Malhotra says. “We may be able to improve the situation if we can equip people to detect and deter the unethical behavior of others.”

Previous studies examined the linguistic differences between lies and truthful statements. But this one went a step further, considering the differences between flat-out lies and deception by omission — the willful avoidance of divulging important information, either by changing the subject or saying as little as possible.

The researchers recruited 104 participants to play “the ultimatum game,” a popular tool among experimental economists. They discovered that liars tended to use many more words than truth tellers, presumably in an attempt to win over suspicious receivers. The researchers called this “the Pinocchio effect.” In contrast, individuals who engaged in deception by omission used fewer words and shorter sentences than truth tellers. Liars used more swear words than truth tellers, and more third-person pronouns than truth tellers or omitters. Finally, liars spoke in more complex sentences than truth tellers.

DECEPTION

Lie detection is a difficult task, and some techniques work part of the time and only with some people. No single technique is effective all of the time under all conditions. There is no approach or question that enables you to separate lying from truthfulness in every situation. In fact, some methods may decrease the accuracy.

Deception is a fact of life that people seldom think about. There are two primary ways that people lie — concealment and falsification. Concealment occurs when a person evades the question or omits relevant details. Liars often prefer this because it can be difficult to reveal. Without evidence it can be challenging or nearly impossible to validate the truth or falsity of a person’s statement. Concealment is easier than falsification because the liar does not have to remember what was said previously, and it provides numerous built-in excuses. For example, the liar can claim ignorance or a faulty memory.

Concealment often is all that is necessary to mislead another person; however, there are times when falsification is necessary. For example, lying about one’s whereabouts during the time a crime was committed cannot be accomplished by concealment alone. The subject must fabricate a story.

Regardless of the type of lie, the goal is the same — to intentionally mislead another person into believing something the liar knows is false. People who unknowingly provide false information do not demonstrate emotional arousal or other cues associated with deception. It is only when a lie is told knowingly and intentionally that the liar can be expected to display signs.

There is no universal sign of deception. Good investigators avoid focusing on any one behavior and look for clusters (e.g., a subject rubbing the face, shifting posture, and shrugging shoulders). Although none of these behaviors indicate that a person is lying, they often reveal signs of emotional arousal, discomfort, or Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) activation, especially if they break with the subject’s normal baseline demeanor.

The timing and location of a person’s behavior are critical. For example, if a subject shifts posture, smiles, pauses, and touches the face during a break in small-talk conversation, the behaviors probably are of little value. Conversely, if the individual demonstrates the same pattern immediately following a material question, it may indicate emotional arousal or deceit and would require further questioning.

Keep in mind that these signs are just possible indicators of dishonesty. Plus, some liars are so seasoned that they might get away with not exhibiting any of these signs.

“Liars have a dilemma,” says Ray Bull, PhD, a professor of criminal investigation at the University of Derby, in the United Kingdom. “They have to make up a story to account for the time of wrongdoing, but they can’t be sure what evidence the interviewer has against them.”

Both Bull and Hartwig conduct research on criminal investigative interview techniques that encourage interviewees to talk while interviewers slowly reveal evidence.

Their research consistently shows that being strategic about revealing evidence of criminal acts to suspects increases deception detection accuracy rates above chance levels (Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling; Law and Human Behavior). For example, Hartwig and colleagues conducted a series of studies to show that withholding evidence until late in the interview leaves room for guilty suspects to blatantly lie, for instance by denying being in the area of the crime. When the interviewer reveals evidence showing the suspect was there — such as surveillance footage — the suspect has to scramble to make up another lie, or tell the truth. The suspect may admit to being in the area, but still deny the crime. If the interviewer then presents more evidence, such as matching fingerprints from the crime scene, the liar will find it increasingly difficult to keep up the deception (Credibility Assessment: Scientific Research and Applications).

Encouraging interviewees to say more during their interviews also helps to identify liars. “Truth tellers do not immediately say everything they need to say, so when the interviewer encourages them to say more, they give additional information,” says Hartwig. “Liars typically have a prepared story with little more to say. They might not have the imagination to come up with more or they may be reluctant to say more for fear they will get caught.”

Other avenues of research are examining how liars and nonliars talk. Judee K. Burgoon studies sentence complexity, phrase redundancy, statement context and other factors that can distinguish truth tellers from liars (Journal of Language and Social Psychology).

“If liars plan what they are going to say, they will have a larger quantity of words,” she says. “But, if liars have to answer on the spot, they say less relative to truth tellers.” That’s because trying to control what they say uses up cognitive resources. They may use more single-syllable words, repeat particular words or use words that convey uncertainty, such as “might” rather than “will,” she says.

Examining word count and word choice works well for analysis of text, such as interview transcripts, 911 call transcripts, witness and suspect written statements, and in analysis of written evidence such as emails and social media posts. Research is still needed to understand how well investigators can pick up these cues in real time, says Burgoon.

Research is also examining the communication between co-conspirators by exploring how two or more people interact as they try to deceive interviewers (Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society). “In field situations, such as checkpoints and street corners, people conspire and collude to get away with crime and terrorist acts,” says psychologist James Driskell, PhD, president of the Florida Maxima Corporation, a company that conducts research in behavioral and social science. “If two people are lying, they have to concoct a story that is consistent with their co-conspirator so they don’t arouse suspicion,” says Driskell. “If an officer needs to engage them on the street, it would be useful to know what indicators to look for in their responses.”

Compared with truth tellers, when liars tell their story together they tend to not interact with each other and they are less likely to elaborate on each other’s responses, he says. “Truthful dyads are much more interactive as they reconstruct a shared event from memory,” he says.

Who Are the Best Lie Detectors?

Research has consistently shown that people’s ability to detect lies is no more accurate than chance, or flipping a coin. This finding holds across all types of people — students, psychologists, judges, job interviewers and law enforcement personnel (Personality and Social Psychology Review. Particularly when investigating crime, the need for accurate deception detection is critical for police officers who must get criminals off the streets without detaining innocent suspects.

Are certain kinds of people or personality better at spotting lies? That’s a question that Nancy Carter and Mark Weber of the Rotman School of at the University of Toronto asked in their study, published in Social Psychological and Personality Science.

Trusting others may not make you a sucker, they found; it might actually be a sign of your intelligence. The researchers found that people high in trust were more accurate at detecting the liars — the more people showed trust in others, the abler they were to distinguish a lie from the truth. The more faith in their fellow humans they had, the more they wanted to hire the most honest interviewees and avoid liars. Contrary to the stereotype, people low in trust were more willing to hire liars — and less likely to be aware that those people were liars.

“Although people seem to believe that low trusters are better lie detectors and less gullible than high trusters, these results suggest that the reverse is true,” Carter and Weber wrote. “High trusters were better lie detectors than were low trusters; they also formed more appropriate impressions and hiring intentions. People who trust others are not pie-in-the-sky Pollyannas; their interpersonal accuracy may make them particularly good at hiring, recruitment, and identifying good friends and worthy business partners.”

Politicians and Donald Trump, the Master Liar

We learn on a daily basis of a scandal involving politicians, and the situation often includes a litany of lies and deceit.

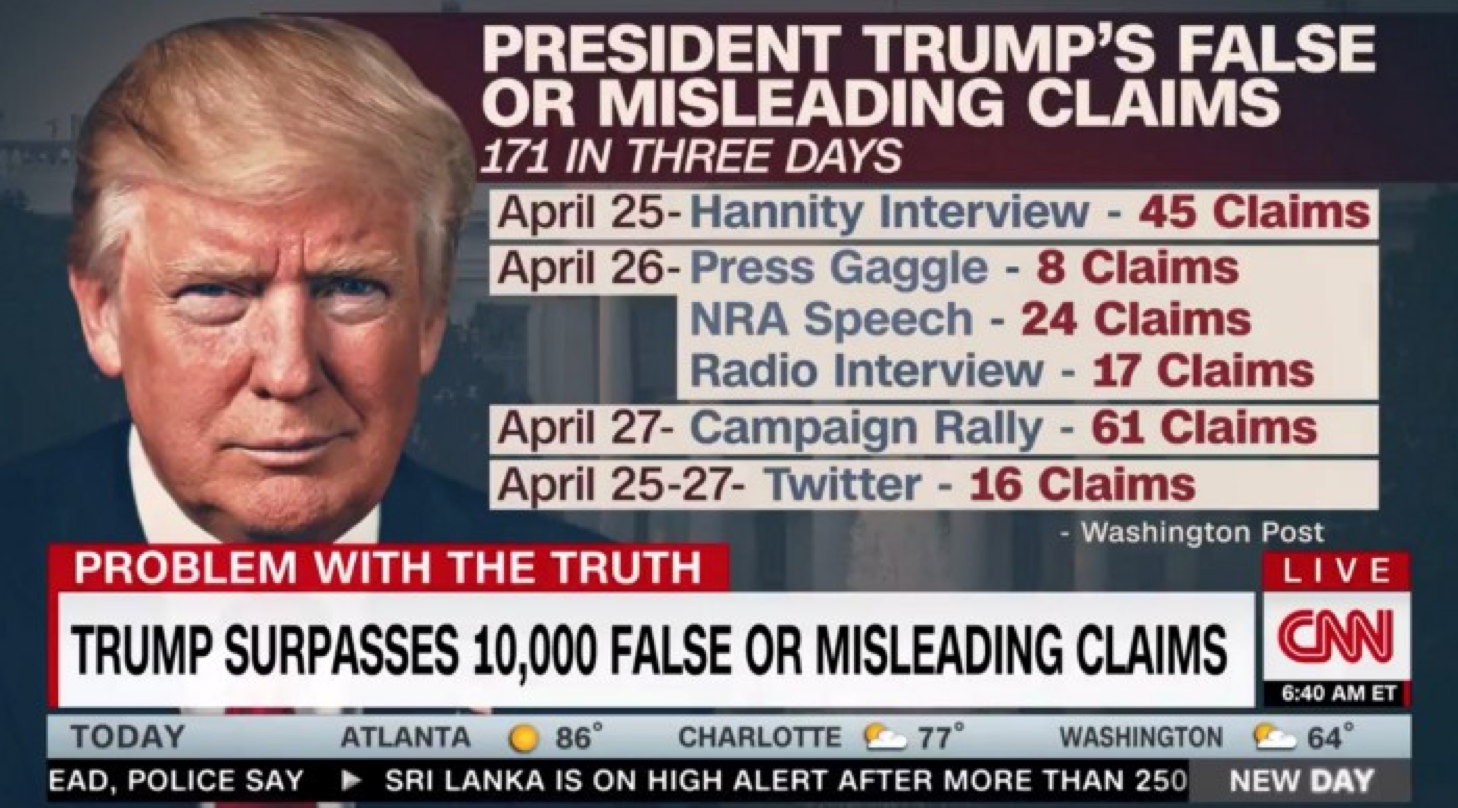

Former President Donald Trump made steady news during his presidency for the sheer and often overwhelming number of lies he told daily. A Washington Post Fact Checker analysis shows that he made 30,573 false or misleading claims during his four years in office, with nearly half of them during his final year in office. Some of Trump’s most infamous liars include his declaration that the coronavirus would disappear like a miracle and various lies about the 2020 election.

The Chicago Tribute reported“Not only does Trump regularly exaggerate the truth, he frequently denies facts that can be observed directly from video or audio tapes. This has led some professionals to diagnose his lying as compulsive or pathological, and many psychologists have pointed out that he is constantly gaslighting his base — a term that refers to a strategic attempt to get others to question their direct experience of reality.”

Trump’s Lying “Tells”

There are a handful of phrases and body language signs that Donald Trump uses that should raise immediate red flags. When the outgoing Republican president tells a story about large, crying men, overcome with emotion because of some amazing thing Trump claims to have accomplished, it’s a telltale sign he’s brazenly lying.

When he tells a story in which unnamed officials keep calling him “sir,” that’s a dead giveaway, too. Likewise, anytime Trump uses the phrase “ahead of schedule,” he’s obviously trying to deceive people.

The former president used another one, which often gets overlooked. Consider this tweet from, in which Trump peddled obvious nonsense about President-elect Joe Biden’s victory: “He didn’t win the Election. He lost all 6 Swing States, by a lot. They then dumped hundreds of thousands of votes in each one, and got caught. Now Republican politicians have to fight so that their great victory is not stolen. Don’t be weak fools!”

Trump falsely claimed more than 100 times that Democrats had “rigged” or “stolen” the 2020 election ahead of January’s deadly insurrectionist attack on the U.S. Capitol,” a Huffington Post analysis found.

As anyone with an even passing familiarity with reality knows, all of this is ridiculous. Trump didn’t win the states he lost; the GOP ticket didn’t achieve a “great victory”; nothing is being “stolen”. Yet the lies continue even until today.

But the phrase that stood out was “got caught.” In other words, as far as the hapless Republican is concerned, nefarious forces not only conspired against him, these rascals and their scheme have since been exposed for all the world to see.

For those uncomfortable with this nonsense, it’s obvious that Trump’s perceived foes were not, in fact, “caught” doing anything except winning a free and fair presidential election by a rather wide margin.

And therein lies the problem: when the outgoing president uses the phrase “got caught,” Trump is nearly always referring to circumstances in which no one has been caught doing anything of the kind.

Trump’s argued, for example, that Biden “got caught” engaging in corruption. That never happened. The Republican also believes that Twitter was “caught” working against conservatives, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) “got caught” cheating, and former FBI Director James Comey “got caught” doing something (it wasn’t clear what). None of this was true.

Similarly, Trump believes that Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton “got caught” committing treason by spying on his 2016 campaign, and “radical left” Democrats “got caught” engaging in some kind of “coup.”

Again, none of these things happened in reality. But the outgoing president not only seems eager to play make-believe, he also seems to believe that by asserting that these ne’er-do-wells “got caught,” people are supposed to assume that his lies have been proven true.They haven’t. “Got caught” is just another telltale sign that the Republican is pushing a line he made up.

Here are more Trump tells:

- If Trump begins any sentence with, “I can tell you this…,” the words that follow will be categorically untrue.

- When he finishes a sentence with “…everyone knows that,” the statement preceding it was a lie.

- Frequent sips of water during White House briefings, public speeches, and official announcements are sure signs that an approaching lie has made its way to his lips, caused his mouth go dry.

- His most flagrant “tell” is capitalization in tweets. He almost always capitalizes words or groups of words that are shameless lies. For example, “FAKE NEWS” appears in almost every tweet, so whatever drove him to Twitter to gripe about is unassailably true.

- Trump, like any sociopath, is incapable of love, kindness, or caring. So when he says, “I love (fill in the blank),” don’t believe it. He actually hates whatever is in the blank.

- Trump frequently engages insniffling when he speaks. But this is not due to a cold or allergies, it’s his telltale “sniffle of misinformation.

- If Trump flashes his famous triangle hand gesture, peaking his fingertips in a downward prayer position, he is cooking up a fantastic fable.

Summary:

Lies, misinformation, disinformation, deception and fraud seem to be far more prevalent than a healthy society should tolerate. It’s important for individuals and organizations to maintain both a positive frame of mind, but healthy skepticism at the same time.

Read my latest book available on Amazon:Toxic Bosses: Practical Wisdom for Developing Wise, Moral and Ethical Leaders,