By Ray Williams

June 20, 202

Father’s Day provides an opportunity to reflect on the importance and state of fatherhood in our society, and assess how far we’ve come in valuing that critical parenting role.In Western countries, particularly the U.S., fatherhood is undergoing a traumatic experience that exposes conflicts in the male identity.

An Unanticipated Benefit from the COVID-19 Pandemic

“Men are torn between the breadwinning role and parenting,” said Daniel L. Carlson, assistant professor of family and consumer studies at the University of Utah.

“We know that most women say they won’t marry a man who won’t be a breadwinner. But then the men also want to be involved dads. Then at the workplace, they’re expected to be only the breadwinner with no other responsibilities and, when push comes to shove, work wins.”

Sometimes, big shifts require an external tipping point, and Carlson and other experts believed Covid-19 might provide just that when it comes to men reconciling their work and family lives.

A recent survey conducted by Carlson and colleagues found that, according to both men and women, men are doing more child care and housework during the pandemic than they did before.

A later study from the Council on Contemporary Families, released in May, reports that housework and child care have become more equal. “Prior to the start of the pandemic, 26 percent of parents reported sharing routine housework relatively equally with their partner, 41 percent reported sharing care for young children relatively equally … and 45 percent reported sharing care of older children,” according to the report. “A little more than a month after the start of the pandemic, 41 percent of parents reported sharing housework with their partners — a significant 58 percent increase — while the percentage of partnered parents reporting equal sharing care of young and older children also increased significantly, to 52 percent and 56 percent respectively.”

This research is consistent with findings from Harvard University as well as internatinal studies from Canada, Turkey, the Netherlands and elsewhere. According to the Harvard study, 68% of dads said they report feeling closer or much closer to their children since the pandemic, and 57% percent said they are appreciating their children more.

Also, a recent study from New America based on data collected before the pandemic found that fathers today want to be emotionally connected to their children. In the survey, more fathers rated “showing love and affection” and “teaching the child about life” as “very important” rather than being the breadwinner.

Titan Alon, assistant professor of economics at University of California, San Diego, said that the pandemic will also likely lead to structural changes at work that will make dads’ deeper engagement with family life possible.

“What we expect culturally, and what the economics of the day require, are linked,” Alon said. “The old norms and models [of work] don’t work in the modern economic environment.”

The pandemic will lead to a rise in flexible work arrangements, which are more common in other countries, Alon believed. While businesses have been slowly moving in this direction for a long time, the pandemic has forced them to both smooth out the kinks and fine-tune the technology to make it functional. Just as importantly, employees and bosses are getting used to it, and Alon suspected that this newfound comfort with working from home will change how we work moving forward.

For Stephen Dypiangco, co-founder of Dadventures, the pandemic has led to opportunities for men to share their feelings about fatherhood. Dypiangco believed that male isolation, and men’s inability to be vulnerable with one another, is one of the reasons dads do less parenting.

Dads don’t feel as comfortable as women admitting that they are exhausted or scared, and therefore aren’t able to work through the complicated feelings that come with parenting. He said dads need more opportunities to explore themselves as parents, which will give them permission to let go.

“There’s been so much out there for moms, Facebook groups and more to talk about parenting … and basically nothing for dads,” he said. It’s a problem he hopes to help fix, one pandemic dad group text at a time.

It remains to be seen whether this increase in men’s active involvement in fatherhood and sharing of parental and home duties will continue after the pandemic subsides, or will there be a return to previous times when fathers were less involved in parenting their children.

A Brief Look at the History of Fatherhood

In an article by Joel Christensen, he describes the importance of fathers to Greek culture and myths: “Fathers occupy an outsized place in Greek myth. They are kings and models, and too often challenges to be overcome. In Greek epic, fathers are markers of absence and dislocation.”

The Roman concept of familia described the people in a household subject to the authority of the master of the household, the paterfamilias. Members of a household shared a common subjection to the father first and blood or other ties second. Fathers, as patresfamilias, had complete power over the household. This included sexual rights to the slaves and freedmen or women who comprised his household. The ultimate power, in fact, lay in a Roman father’s hands: patria potestas, the power of life and death.

Roman fatherhood was volitional, legal, and social, rather than biological, and Adoption was common. Adoption also solved problems of inheritance and could be enacted posthumously in a deceased father’s will.

The power of fathers in ancient Rome reverberated beyond the family to affect Roman public life in myriad ways. The father-son relationship was a model for political relationships between men of different rank. Fathers represented their entire household politically, including their sons. Members of the Roman senate addressed one another as patres conscripti (“assembled fathers”), indicating that they served as leaders of households and ruled as fathers of Rome. Sons received citizenship through their fathers, albeit a second-class one. Responsible for raising and educating their sons as future full citizens, fathers went about the city and their political duties accompanied by their sons.

Citizenship, military service, and fatherhood were men’s responsibilities to Rome. Men divorced and remarried if a wife was barren and quickly remarried should their wives die in childbirth. Leaving behind many children was a civic duty, a necessary rite of citizenship.

Under Roman law paternal authority was complete. The law permitted fathers to disinherit sons and theoretically, it also permitted them to kill their sons, although in the few cases where fathers exercised this right it was for high crimes such as treason.

The conjugal family was the basic family unit quite early in European family history–most certainly by 1000 AD. While this truncated family did not much alter a father’s authority in law, it would seem to improve his wife’s place in the home slightly, now that marriage was seen as a lifelong bond, and it meant that fathers would expect to see their sons leave their household upon marriage. Fathers took charge of sons’ upbringing as they grew less dependent on their mothers for full-time care, a pattern that would persist in later centuries. Inheritance practices tended to heighten the emotional and economic dynamics of fathers’ relationships with their oldest son.

Yet, medieval Christianity moderated paternal power and altered the view of fatherly responsibility. Children were no longer seen as the property of the fathers; instead they were a responsibility entrusted to their fathers’ safekeeping by God. Fathers were now expected to support and protect their offspring, even their illegitimate children.

Fathers were responsible for the education of sons, once they reached the age of seven, and focused on guiding them into a suitable occupation. Among the aristocracy, fathers might decide upon the education of their sons, but would not carry out this education themselves. Instead boys were trained for knighthood in another noble house, perhaps that of a maternal or paternal uncle. Urban fathers of means apprenticed their sons, placing them under the authority of another father. Peasant fathers were those fathers most likely in medieval times to rear their children through adolescence in their own households. By the medieval period, all the components of modern fatherhood were present: breadwinner, educator, and at least in imagery, playmate. However the weight and meaning assigned to these roles shifted over time.

Protestantism also demanded a new role of men in the home: that of religious educator. The Reformation has been described as the “heyday” of the patriarchal nuclear family. The Protestant Reformation and ensuing Counter-Reformation in the Catholic Church resulted in a reform of family life, often in ways that cemented fathers’ authority.

Patriarchy received a boost when English colonists constructed communities in the New World. English colonists expanded on the English laws and practices of family government, creating fathers who were among the most powerful household heads in the Western world, largely because of their control of the labor of subordinate household members, children, servants, and slaves. English fathers, or any in Western Europe, had the ability that fathers in the New World had to force marriage, sell servants, or the authority to take a life. Chattel slavery and indentured servitude granted household heads control of their labor force and concentrated tremendous patriarchal power in the hands of wealthy men.

The Victorian patriarch, the mythically autocratic and stern father largely removed from the affairs of the household, is more a construction of the present than the past. While it may not have absented fathers from the home completely, the Industrial Revolution changed the days and duties of men and families dramatically, affecting the location and meaning of work, leisure, and parenting.

The Victorian father was, contrary to popular belief, quite domestic, and according to historian John Tosh, in England, Victorian fathers were more domestic than fathers either before or since. Home was a place where men ruled, but also a place that ministered to men’s emotional needs. The family in the home was to make up for the dramatic social and economic changes of industrialization that threatened to turn men into mere drones. Home life and fatherhood was expected to rejuvenate men and provide meaning in an increasingly “heartless” world. In addition, domestic life was expected to replace the more homosocial leisure distractions outside the home of the English male middle class.

Fathers’ legal powers were winnowed quite significantly in the Victorian era. In the United States coverture, the common-law system in which males represented the household to the public, diminished with the passage of married women’s property acts, laws that gave women control of their earnings, and those that provided custody to mothers in the case of divorce. In addition, public education systems took over the education of youth in nearly every state by 1880. Many of the nineteenth-century reform movements, including temperance and abolition, at heart, dealt with the problem of the corrupt or out-of-control patriarch.

During the 1930s when the global economic crisis prevented many men from performing as family breadwinners and as the psychological community embraced the theories of Sigmund Freud, advisors elaborated a new role for fathers beyond that of playful companions. Father was a role model for the proper sex role development of both sons and daughters. This attention reflected anxieties about masculinity in the home as massive unemployment reduced the power of fathers to provide for their families. Men and women saw male authority as derived from their breadwinning role

Three twentieth-century developments challenged this division of labor which has proven, not surprisingly, quite resistant to change. The postwar Baby Boom (1946–1964) ushered the ideal of fatherly participation further into the mainstream. Experts, mothers, and fathers themselves insisted, “Fathers are parents, too!”

The postwar years brought another change to American families and those in Western Europe as well: the increased participation of married women in the labor force. With fathers as primary breadwinners, the occasional child-care chore was all that most families demanded of men, but as women increasingly shared the breadwinning role while shouldering the lions’ share of the child-care and household work, their demands and persuasive power escalated.

Continued economic inequality between men and women was present and the volitional quality of participatory fatherhood in the new millennium as well as the strong association of fatherhood with power. Breadwinning remains father’s principle responsibility and the workplace remains family unfriendly, while more and more, mothers must balance their commitments to work and family. Fathers are no longer patriarchs, but they strive to be more than breadwinners and pals. The twenty-first-century father looks for self-identity, meaning, and satisfaction in his relationships with his children.

“I think the key change for the invention of the modern father is in the 1920s,” says historian Robert L. Griswold, author of Fatherhood in America: A History. “The advent of the automobile” is part of the broader growth of consumer society, heaping on the pressure on breadwinners to “earn more bread,” as Griswold puts it, just as families were also realizing just how much a father’s non-economic role in the family mattered.

The next major shift is one that continues to this day. Since the women’s liberation movement took off in the late ’60s, leading to more opportunities for women pursue a wider range of job and education opportunities, the image of the family breadwinner changed. The rise of no-fault divorces also led to more kids splitting time between homes. Though there had always been women who supported their families, and families that didn’t conform to the mom-dad-kids model, in the late 20th century American society began to recognize that truth in a new way. And as Americans in families of all types struggled to figure out what it meant to be a “good” parent, fatherhood was part of the battle.

In keeping with the spirit of the times, the “New Fatherhood” movement came back in full force, with renewed concern about the role fathers would now be expected to play in the family as it evolved.

“More children will go to sleep tonight in a fatherless home than ever in the nation’s history,” TIME declared in a cover story on fatherhood that hit newsstands for Father’s Day 1993, amid increased public awareness of this situation. “Talk to the experts in crime, drug abuse, depression, school failure, and they can point to some study somewhere blaming those problems on the disappearance of fathers from the American family. But talk to the fathers who do stay with their families, and the story grows more complicated. What they are hearing, from their bosses, from institutions, from the culture around them, even from their own wives, very often comes down to a devastating message: We don’t really trust men to be parents, and we don’t really need them to be.”

The idea that fathers get the message that they’re not needed — especially now that social media has increased the platforms by which ideas about good parenting can be offered — is still an issue. For example, a study that recently appeared in The Journal of Child and Family Studies suggests that such as “maternal gate-closing,” the idea that mothers still know the most about childcare, could be overwhelming fathers and negatively affecting their confidence in their own ability to parent.

Research on the Benefits of Engaged Fatherhood

A committee assembled by the Board of Children and Families of the National Research Council, concluded “children learn critical lessons about how to recognize and deal with highly charged emotions in the content of playing with their fathers. Fathers, in effect, give children practice in regulating their own emotions and recognizing others’ emotional clues.” At play and in other realms, fathers tend to stress competition, challenge, initiative, risk taking and independence. Mothers, as caretakers, stress emotional security and personal safety. Father’s involvement seems to be linked to improved quantitative and verbal skills, improved problem-solving ability and higher academic achievement for children.

Men also have a vital role to play in promoting cooperation and other “soft” virtues. Involved fathers, it turns out according to one 26 year longitudinal research study may be of special importance for the development of empathy in children. Family life-marriage and child rearing-is a civilizing force for men. It encourages them to develop prudence, cooperativeness, honesty, trust, self-sacrifice and other habits that can lead to success as an economic provider by setting a good example.

Beyond that, fathers—men—bring an array of unique and irreplaceable qualities that women do not ordinarily bring. Some of these are familiar, if sometimes overlooked or taken for granted. The father as protector, for example, has by no means outlived his usefulness. And he is important as a role model. Teenage boys without fathers are notoriously prone to trouble. The pathway to adulthood for daughters is somewhat easier, but they still must learn from their fathers, as they cannot from their mothers, how to relate to men. They learn from their fathers about heterosexual trust, intimacy, and difference. They learn to appreciate their own femininity from the one male who is most special in their lives (assuming that they love and respect their fathers). Most important, through loving and being loved by their fathers, they learn that they are worthy of love.

Recent research has given us much deeper—and more surprising—insights into the father’s role in child rearing. It shows that in almost all of their interactions with children, fathers do things a little differently from mothers. What fathers do—their special parenting style—is not only highly complementary to what mothers do but is by all indications important in its own right.

For example, an often-overlooked dimension of fathering is play. From their children’s birth through adolescence, fathers tend to emphasize play more than caretaking. This may be troubling to egalitarian feminists, and it would indeed be wise for most fathers to spend more time in caretaking. Yet the fathers’ style of play seems to have unusual significance. It is likely to be both physically stimulating and exciting. With older children it involves more physical games and teamwork that require the competitive testing of physical and mental skills. It frequently resembles an apprenticeship or teaching relationship: “Come on, let me show you how.” The way fathers play affects everything from the management of emotions to intelligence and academic achievement. It is particularly important in promoting the essential virtue of self-control. According to one expert, “Children who roughhouse with their fathers . . . usually quickly learn that biting, kicking, and other forms of physical violence are not acceptable.” They learn when enough is enough.

Other research also provides insight into the various and unique benefits a dad can bring into their home and children’s lives. The following examples describe studies demonstrating the potential results from a father’s positive effective parenting.

- According to one study, playing with fathers, including roughhousing, helps children develop self-control, problem-solving skills, and self-regulation skills.

- Further, children who are well-bonded and loved by involved fathers, tend to have less behavioral problems, and are somewhat inoculated against alcohol and drug abuse. Yet when fathers are less engaged, children are more likely to drop out of school earlier, and to exhibit more problems in behavior and substance abuse.

- Research indicates that fathers are as important as mothers in their respective roles as caregivers, protectors, financial supporters, and most importantly, models for social and emotional behavior.

- In a 2002 review of various studies on the father’s role in child development, researchers found consistent evidence that children of involved fathers were more likely to show cognitive competence and educational success than those whose fathers weren’t engaged, and were also more likely to enjoy school and take part in more extracurricular activities.

- Over the years, research has shown that kids with good fathers are more likely to grow up without aggression, low self-esteem, or behavioral issues. Involved fatherhood has been linked with greater resilience to stress and frustration, as well as better abilities to solve problems and adapt. Kids who grow up with a dad present are less likely to develop substance abuse problems or to become incarcerated as adults. Perhaps most importantly, kids who grew up with involved fathers have been shown to have a lower risk of depression.

- . According to a 2009 study using data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, children without their biological fathers were more likely to be abused or neglected, oftentimes by the non-biological father or the man dating their mother. When a biological dad is around, kids are more likely to be protected.

- In an analysis of over 100 studies on parent-child relationships, it was found that having a loving and nurturing father was as important for a child’s happiness, well-being, and social and academic success as having a loving and nurturing mother.

- According to child psychiatrist Kyle Pruett, a father’s more active play style and comparatively slower response to a toddler or infant experiencing frustration serve to promote problem-solving competencies and independence in the child.Kyle D. Pruett, Fatherneed: Why Father Care is as Essential as Mother Care for Your Child.

- “We’re now finding that not only are fathers influential, sometimes they have more influence on kids’ development than moms,” said Ronald Rohner, the director of the Center for the Study of Interpersonal Acceptance and Rejection at the University of Connecticut. Behavior problems, delinquency, depression, substance abuse and overall psychological adjustment are all more closely linked to dad’s rejection than mom’s, Rohner said.

- Research from the University of Pennsylvania indicates that children who feel a closeness and warmth with their father are twice as likely to enter college, 75 percent less likely to have a child in their teen years, 80 percent less likely to be incarcerated and half as likely to show various signs of depression according to Frank Furstenberg and Kathleen Harris, “When and Why Fathers Matter: Impacts of Father Involvement on Children of Adolescent Mothers,” in Young Unwed Fathers: Changing Roles and Emerging Policie.

- Children’s values, beliefs, emotional expression and social development are strongly associated with fathering. Kids are better regulated emotionally, more resilient and more open-minded when their fathers are involved in their education and socialization.

- Fortunately for dads, biology is there to back up good parenting. Hormonal studies have revealed that dads show increased levels of oxytocin during the first weeks of their babies’ lives. This hormone, sometimes called the “love hormone,” increases feelings of bonding among groups. Dads get oxytocin boosts by playing with their babies, according to a 2010 study published in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

- Mothers and other parenting partners are healthier and happier when fathers are highly engaged with their kids. Men who care for and support their kids benefit too – with improved self-image, life purpose and relationships. And communities gain increased trust and safety from the relationships built when fathers positively participate in their kids’ activities, schooling and social networks.

The Bad News on the State of Fatherhood in the U.S. Prior to the Pandemic

Some would argue that America is rapidly becoming a fatherless society, or perhaps more accurately, an absentee father society. The importance and influence of fathers in families has been in significant decline since the Industrial Revolution and is now reaching critical proportions. The near-total absence of male role models has ripped a hole the size of half the population in many urban areas. For example, in Baltimore, only 38 percent of families have two parents, and in St. Louis the portion is 40 percent.

America is the only developed country in the world that doesn’t mandate some form of paid maternity leave. It doesn’t offer paid leave for new fathers, either.

Across time and cultures, fathers have always been considered essential—and not just for their sperm. Indeed, no known society ever thought of fathers as potentially unnecessary. Marriage and the nuclear family—mother, father, and children—are the most universal social institutions in existence. In no society has the birth of children out of wedlock been the cultural norm. To the contrary, concern for the legitimacy of children is nearly universal.

As Alexander Mitscherlich argues in Society Without A Father, there has been a “progressive loss of the father’s authority and diminution of his power in the family and over the family.”

“If present trends continue, writes David Popenoe , a professor of sociology at Rutgers University and author of Families Without Fathers, says , “the percentage of American children living apart from their biological fathers will reach 50% by the next century.” He argues “this massive erosion of fatherhood contributes mightily to many of the major social problems of our time…Fatherless children have a risk factor of two to three times that of fathered children for a wide range of negative outcomes, including dropping out of high school, giving birth as a teenager and becoming a juvenile delinquent.”

In the 2019 report, “Father and Child Well Being: A Scan of Current Research,” by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the National Responsible Fatherhood Clearinghouse, concluded there is a growing percentage of single custodial parents are fathers.

Extensive research has been conducted on the topic by David Blankenhorn, author of Fatherless America, chair of the National Fatherhood Initiative and founder/president of the Institute for American Values, organization, and by Popenoe and scores of other researchers. A sample of their findings follows.

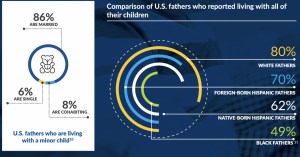

- Approximately 30% of all American children are born into single-parent homes, and for the black community, that figure is 68%;

- Among the 49 countries, the U.S. is tied with Colombia for the second highest rate of children growing up in single parent homes. Only South Africa has a higher rate. To put this in perspective, the U.S. trails not only every developed country (Western and Eastern) but nearly every developing one.

- Fatherless children are at a dramatically greater risk of drug and alcohol abuse, mental illness, suicide, poor educational performance, teen pregnancy, and criminality, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics.

- 72% of adolescent murderers grew up without fathers. 60% of America’s rapists grew up the same way.

- 63% of 1500 CEOs and human resource directors said it was not reasonable for a father to take a leave after the birth of a child.

- 71% of all high school dropouts come from fatherless homes according to the National Principals Association Report on the State of High Schools.

- 90% of all homeless and runaway children are from fatherless homes.

- 85% of all children that exhibit behavioral disorders come from fatherless homes according to a study by the Center for Disease Control.

- A large survey conducted in the late 1980s found that about 20% of divorced fathers had not seen his children in the past year, and that fewer than 50% saw their children more than a few times a year.

- In a longitudinal study of 1,197 fourth-grade students, researchers observed “greater levels of aggression in boys from mother-only households than from boys in mother-father households,” according to a study published in the Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology.

- The Scholastic Aptitude Test scores have declined more than 70 points in the past two decades; children in single-parent families tend to score lower on standardized tests and to receive lower grades in school according to a Congressional Research Service Report.

Blankenhorn argues that America is facing not just the loss of fathers, but also the erosion of the ideal of fatherhood. Few people doubt the fundamental importance of mothers, Popenoe comments, but increasingly the question of whether fathers are really necessary is being raised and said by many to be a merely a social role that others-mothers, partners, stepfathers, uncles and aunts, and grandparents can play.

“The scale of marital breakdowns in the West since 1960 has no historical precedent that I know of,” says Lawrence Stone, a noted Princeton University family historian, “There has been nothing like it for the last 2,000 years, and probably longer.” Consider what has happened to children. Most estimates are that only about 50% of the children born during the 1970-84 “baby bust” period will still live with their natural parents by age 17-a staggering drop from nearly 80%.

Despite current interest in father involvement in families, an extremely large proportion of family research focuses on mothers and children. Health care agencies and other organizations exclude fathers, often unwittingly. Starting with pregnancy and labor and delivery most appointments are set up for mothers and held at times when fathers work.

The same is true for most pediatric visits. School records and files in family service organizations often have the child’s and mother’s name on the label, and not the father’s. In most family agency buildings, the walls are typically pastel colors, the pictures on the wall are of mothers, flowers and babies, the magazines in the waiting room are for women and the staff is predominantly female. In most welfare offices, fathers are not invited to case planning meetings, and when a home visitor is greeted at the door by a man, she often asks to speak with the mother. Given these scenarios, fathers are likely to get the message that they are invisible or irrelevant to their children’s welfare, unless it involves financial support.

Popenoe and others have examined the role of fathers in raising children and found there are significant differences than that for mothers. For example, an often-overlooked dimension of fathering is play. From their children’s birth through adolescence, fathers tend to emphasize play more than caretaking. The play is both physically stimulating and exciting. It frequently resembles an apprenticeship or teaching relationships, and emphasizes often teamwork and competitive testing of abilities. The way fathers play affects everything from the management of emotions to intelligence and academic achievement. It is particularly important in promoting the essential virtue of self-control.

Mark Finn and Karen Henwood, writing about the issue of masculinity and fatherhood, in the British Journal of Social Psychology, argue that the traditional view of masculinity, with its focus on power, aggression, economic security, and “maleness”, and the emerging new view of fatherhood, which incorporates many aspects of motherhood is a source of struggle for many men who become fathers.

In a study of fatherhood in popular TV sitcoms, Timothy Allen Pehlke and his colleagues concluded that fathers are generally shown to be relatively immature, unhelpful and incapable of taking care of themselves in comparison with other family members. In addition, the researchers found that fathers often served as the butt of family members’ jokes. All of these characterizations, while the intention may be humor, depicted fathers as being socially incompetent and objects of derision.

In a study of depictions of fathers in the best-selling children’s picture books, researcher Suzanne M. Flannery Quinn concluded that of the 200 books analyzed, there were only 24 books where the father appears alone, and only 35 books where mother and father appear together. The author concludes, “because fathers are not present or prominent in a large number of these books, readers are given only a narrow set of images and ideas from which they can construct an understanding of the cultural expectations of fatherhood and what I means to be a father.”

Guy Garcia, author of The Decline of Men: How The American Male is Tuning Out, Giving Up and Flipping Off His Future, argues that many men bemoan a “fragmentation of male identity,” in which husbands are asked to take on unaccustomed familial roles such as child care and housework, while wives bring in the bigger paychecks. “Women really have become the dominant gender,” says Garcia, “what concerns me is that guys are rapidly falling behind. Women are becoming better educated than men, earning more than men, and, generally speaking, not needing men at all. Meanwhile, as a group, men are losing their way.”

“The crisis of fatherhood, then is ultimately a cultural crisis, a sharp decline in the traditional sense of communal responsibly, ” contends Popenoe; “It therefore follows that to rescue the rescue the endangered institution of fatherhood, we must regain our sense of community. There is still a wide gap between research results and the true acceptance of the value of fathers, with many fathers expressing the feeling that they continue to be second-class citizens in the world of their children. Books, magazines, and morning television shows are filled with information about and for mothers and mothering. How many comparable ones have you seen about fathers? It’s only recently that domestic courts, recognizing the research on parenting and fathers, have moved to greater equal child custody decrees. Fathers who want to become more actively involved in their children’s lives often hit barriers from employers, the media, and even their wives, who may feel threatened by a child calling for “Daddy” instead of “Mommy.” I’ll deal with these barriers in greater depth in forthcoming blogs, as well as issues relating to the absent father, the alienated father, and the divorced father.

What Can Be Done to Strengthen Fatherhood?

In recent decades, the changing economic role of women has greatly impacted the role of fathers. Between 1948 and 2001, the percentage of working age women employed or looking for work nearly doubled–from less than 33 percent to more than 60 percent. Their increase in financial power made paternal financial support less necessary for some families. In tandem with the growing autonomy of women, related trends such as declining fertility, increasing rates of divorce and remarriage, and childbirth outside of marriage have resulted in a transition from traditional to multiple undefined roles for many fathers. Today’s fathers have started to take on roles vastly different from fathers of previous generations.

The Scandinavian Example

Of all the evolutionary and cultural shifts in fatherhood, some of the most interesting social experiments have been conducted in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden Their laws are designed to foster dual earner/caregiver families and involved fathering. The relatively firm national and individual financial footing in these countries has made some of these policies viable. Childcare is subsidized, and a small proportion of adults live below the poverty line. While formal marriage has waned, resulting in about half of children born into marital unions, around 90 percent of children are initially raised in households containing both parents.

In 1974, Sweden was the first country to allow fathers to use parental leave. By 1993, Norway had granted four weeks of paternal leave, and by 2011 that had jumped to twelve weeks. Paternal leave is more likely to be used by better educated, wealthier, native-born men. Other kinds of parental buffers are provided. As an example, fathers or mothers can stay home with a sick child, with a limited number of such days paid for in Sweden and Norway and the public sector in Denmark. In the event of parents’ splitting, rules govern custody and visitation. The law is designed to privilege the child’s interests rather than, as had been the case, the mother’s; the law provides for normative joint custody.

In the past several decades, Scandinavian fathers have increased the amount of time they spend in childcare, even if the amount of time is lower than mothers. In Sweden, but not Norway, men take on a greater proportion of childcare duties when the child’s mother works full-time.

Our children can’t continue to grow up in a world where only women raise them, either at home or in early learning and care. Countries like Canada can support this needed change by providing quality universal child care while nurturing a more stable early childhood profession and intentionally creating a more gender-balanced early childhood workforce.

Through better wages and work conditions for all early childhood educators and mentoring for men entering the early childhood education profession, the world of early learning and care could become enriched as a whole and children would experience a greater diversity of caregivers.

At the same time, governments and society could gain economically by investing more in quality early learning and care: for every dollar invested, the return ranges from 1.5 to almost three dollars with the benefit ratio for children in lower socio-economic environments being higher. This investment would boost children’s long-term developmental outcomes.

How can American society ensure that healthy competition, emotional openness and respect for women are widespread among future generations of men and fathers? Part of the answer is by valuing loving, supportive fathering.

That means more support for fathers in workplaces, public policy and institutions. Paid family leave, flexible work arrangements and integration of fathers into prenatal and postnatal care are all effective ways to encourage fathers to be more involved.

Many fathers increased their share of child care tasks during the COVID-19 pandemic. These shifts may become permanent, ultimately changing cultural values around parenting and gender roles.

Read my new book, available on Amazon:Toxic Bosses: Practical Wisdom for Developing Wise, Moral and Ethical Leaders, where I examine in detail the impact that toxic bosses have on employee well-being.