Mindless and Chaotic Workplaces

By Ray Williams, January 30, 2019

The following is an excerpt from my book, Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces.

Of the book, Top 50 Management Guru Marshall Goldsmith says: “Any leader, especially those who are striving to implement change at work, will benefit from this provocative and pragmatic book. The book will be especially helpful to those working in a broken environment.”

Mindless working is this century’s cocaine, a problem with no name.

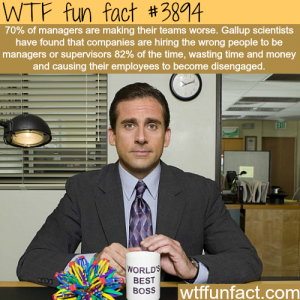

Mindlessness can be defined as “having no intelligent purpose, meaning, or direction; giving or showing little attention or care; heedless.” Mindlessness at work has become a global touchstone of mockery, and entertainers have enchanted audiences worldwide with comedies featuring mindless managers.

In the TV series ‘The Office,” Steve Carrell, playing the role of Michael Scott as Regional Manager of a Dunder-Mifflin branch in Scranton, Pennsylvania, epitomizes mindless behavior, which is characterized by a reliance on old, often outdated management practices and a reduced awareness of one’s social and physical world.

While some argue that mindlessness is a necessity in the work environment, a closer examination reveals that mindlessness is rarely, if ever, beneficial because it closes us off to creative possibilities, freezes our responses, and prevents needed change. Mindlessness can be part of the cultural makeup of an organization.

The movie “Office Space” highlights the mindless business culture many people experience as employees. In such a workplace, categories of thinking are rarely revisited, context rarely matters, and individual differences and strengths are irrelevant to the job. The character Milton in the movie exemplifies such a mindless bureaucrat, who can only function in a culture that values mindless behavior. The main character, Peter, ultimately gets fed up by this mindless culture after several bosses ask him whether he had read an irrelevant office memo. This story highlights how a culture of mindlessness can lead employees to unhappiness and active disengagement. Active disengagement occurs when employees start undermining the company by sabotaging its operations. Peter and two of his co-workers in the film take revenge by developing a plot to tweak the payment system so that small sums of customer payments will be transferred to their account.

Mindless individuals are much like robots. Their thoughts, emotions, and behaviours are determined by programmed routines based on things they have learned in the past. It is theorized by some researchers that mindlessness is often a consequence of the tendency to apply previously formed mindsets to current situations This locks these individuals into a repetitive and often unconscious approach to daily life.

When people are mindless, they are trapped in a rigid perspective, insensitive to how situations can change even subtly. The past dominates, and they behave much like automatons without knowing it, where rules and routines govern their behaviour. Essentially, they freeze their understanding and become oblivious to subtle changes that would have led them to act differently, if only they were aware of the changes. Mindlessness is pervasive and costly and operates in all aspects of people’s lives. Although people can see it and feel it in other people, they can be blind to it in themselves.

Cognitive Overload

The average American reads or absorbs 34 gigabytes of data every single day, according to the 2008 report from University of California, San Diego. To put these numbers in an analogy, one gigabyte is equivalent to a symphony in high-fidelity sound or a broadcast quality movie. According to the researchers, the main effect of information overload is our attention or focus is continually interrupted all too often, which in turn interferes with our ability for reflection and deeper thinking.

Our colossal consuming data habits are not only crowding out essential neurological downtime, but they’re creating a chemical addiction according to the researchers When we consume media — from watching TV to surfing the Net, and from playing videogames to using social media — we’re triggering the brain chemical dopamine. Dopamine creates a “high,” and pleasure response and thus we are wired to do what it takes to maintain this elevated state. When the dopamine levels decrease, we begin to look for diversions that will restore the high levels of pleasure.

In the absence of stimulation, and the corresponding dopamine high, we’re likely to feel bored. As a result, many of us become stimulation junkies and incessant multitaskers. In the New York Time sarticle, “Attached to Technology and Paying the Price,” Matt Richtel wrote, “While many people say multitasking makes them more productive, research shows otherwise. Heavy multitaskers actually have more trouble focusing and shutting out irrelevant information, scientists say, and they experience more stress. And scientists are discovering that even after the multitasking ends, fractured thinking and lack of focus persist.”

A study of 2,250 adults by two Harvard University psychologists found that peoples’ minds wander an astounding 47% of the time. They concluded that a “human mind is a wandering mind, and a wandering mind is a unhappy mind.” Our minds naturally wander. We wander into regrets about the past and worries about the future. We replay scenarios over and over again, not because we want to, but because we can’t seem to stop. Wandering minds also compromise the quality of peoples’ work. “High quality attention is the productive basis for knowledge workers and we do very little to cultivate that essential resource,” says Jeremy Hunter a professor at the Peter F. Drucker School of Management in Los Angeles.

Mindless workers are disconnected from themselves and see work as a haven for an emotionally unpredictable world; they are on automatic pilot, allowing work to engulf them; they seek an emotional and neuro-physiological payoff from frantic working; get an adrenaline rush from meeting impossible deadlines; and they are preoccupied with work no matter where they are.

Teresa Amabie and her colleagues at Harvard Business School evaluated the daily work patterns of more than 9,000 individuals working on projects that required creativity and innovation. They found that the likelihood of creative thinking is higher when people focused on one activity for a significant part of the day and collaborate with only one person. Conversely, when people had fragmented days with many activities and meetings and discussions with lots of people, their creative thinking declined significantly.

CEOs and senior executives calendars are often booked back to back all day based on the proposition that it is both necessary and leads to greater productivity, despite the evidence that it doesn’t. CEOs have to learn how to delegate most matters to subordinates, and return contacts from others when convenient. They need to edit or shut off the flow of incoming information and completely unplug for blocks of time, and give up the need to be on top of everything.

Research on multitasking, which often incorrectly, is associated with greater productivity and shows each additional task you undertake concurrently with others reduces performance in them all and it can take up to 15 minutes to restore concentration following a distraction due to a “resetting” process in the brain. While the brain’s basal ganglia operates by distributed association and can draw on almost unlimited capacity, the prefrontal cortex operates via serial processing, has limited daily capacity, and struggles constantly with what to prioritize and bring to conscious thought.

Requiring a serial processor to multitask is a tall order. Studies of multitaskers show that performance deteriorates significantly as soon as they attempt more than one cognitive task at a time. Even though we can comfortably undertake several programmed tasks simultaneously, this is not true of tasks requiring conscious thinking. Try reading an article while watching the news, or adding a list of numbers while someone is speaking to you. Comprehension and retention on both tasks will be compromised. Recent studies into multitasking specifically show deficits in memory and learning when juggling cognitive load.

Research at Duke University underscores why. Researchers found that more than 40 % of our actions are based on habits, not conscious decisions. Unconscious habits and assumptions aren’t written in stone, but if we don’t bring them into focus then the force of these habits will continue to chart our course. When negative external events occur, internally the mind ruminates and anxiety and stress increase. We become hijacked by internal suffering. When we practice mindful working, we use our minds to navigate workplace woes with clarity, self-compassion, courage and creativity.

Much of contemporary management and leadership literature emphasizes mere tinkering with a paradigm established in the 19th and 20th centuries. The focus of much of the literature has been on planning, analysis, problem-solving and a singular focus on results, with little attention being made to the internal world of leaders—their thoughts and emotions. In this paradigm leaders run on autopilot and can be “mindless.”

There’s a price to pay for our breakneck speed to continuously improve, and produce. Professors Cyril Bouquet and Ben Bryant, cite in Forbes magazine the disastrous collision of two Boeing 747’s in the Canary Islands in 1977, killing 583 people, as a case of poor attention management. They argue that two kinds of attention disorders exacerbate the difficulties companies face in economic downturns–fixation and relaxation. In the case of fixation, leaders can be too preoccupied with a few central signals or information; they ignore everything else. With respect to relaxation, Bouquet and Bryant contend that excessive relaxation follows sustained periods of high concentration. They argue that mindfulness can lessen the attention problems of fixation and relaxation.

The demands of leadership can produce what is known as “power stress,” a side effect of being in a position of power and influence that often leaves even the best leaders physically and emotionally drained. As a result, leaders can easily find themselves moving from an “approach” orientation to their work characterized by being emotionally open, engaged and innovative, to an “avoidance” orientation that is characterized by aversion, irritability, aggression, fear and close-mindedness. If leaders believe they don’t have the time to work through all aspects of a problem they are inclined to be narrow in perspective and take cognitive shortcuts, and become more impulsive and reactive. Their actions, in effect become “mindless” and automatic.

Daniel Siegel, a neuroscientist and author of The Mindful Brain: Reflection and Attunement in the Cultivation of Well-Being,contends that a corporate culture ofcognitive shortcuts result in oversimplication, curtailed curiosity, relianceon ingrained beliefs and the development of perceptional blind spots. Heargues that mindfulness practices enable individuals to jettison judgmentand develop more flexible feelings toward what before may have beenmental events they tried to avoid, or towards which they had intense averse reactions.

David Rock, writing in Psychology Today, argues “busy people who run our companies and institutions tend to spend little time thinking about themselves and other people, but a lot of time thinking about strategy, data and systems. As a result the circuits involved in thinking about oneself and other people, the medial prefrontal cortex, tends to be not too well developed.” Rock says “speaking to an executive about mindfulness can be a bit like speaking to a classical musician about jazz.”

I can relate two stories here from my experience in working with senior executives. The first involves a large non-profit organization in which the CEO had been with the organization for two decades. When I was engaged by the organization, it was having financial difficulties due to declining a declining membership and declining revenues from other sources. Services and programs to members had not substantially changed for over a decade, it was apparent the organization was not keeping up with the times. In meeting with employees and leaders in the organization, I was struck with how limiting discussions were regarding planning for change. Rarely were new ideas presented, or discussed fully when they were presented.

Rather, discussions and plans revolved around the assumption that things would be done the way they always were done, expecting that results would be different. The meetings and discussions had a “mindless” quality to them, where memories of things past drove decisions, and an automatic agreement with things “the way they are,” pervaded relationships. In thatkind of culture, new ideas were not incubated.

The second example was an organization where the leader was a command-and-control leader, of long standing whom employees feared. Rarely did employees have the courage to suggest new ideas or to provide critical feedback on the way things were being done, even though the organization was experiencing difficult times competing with a more progressive organization. The leader of the organization considered any constructive feedback or new ideas to be questioning his authority and he reacted aggressively. He often would respond to challenges by reminding people how successful he had been in the past, and that all his ideas had always worked. Again, a mindlessness had crept into the leader’s behavior and infected employees in the organization.

There’s an irony here. The very structures and systems created by the industrial era and the corporate paradigm, with their focus on set procedures, rules, manuals and automated human behavior are the very things that contribute to people in organizations acting in a mindless, “autopilot” way, often devoid of creativity, passion, joy and happiness—and eventually at the expense of productivity.

To read how leaders can institute mindfulness practices and behaviors as a cost effective, and highly impactful strategy to combat mindlessness, be sure to read my book which goes into detail on what to do.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.