By Ray Williams

June 15, 2021

Mindfulness practices have moved into the workplace and become a key leadership and organizational development strategy.

Mindfulness has developed through thousands of years of cultural evolution as an antidote to the natural habits of our hearts and minds that make life difficult. Mindfulness holds the promise not only for reducing stress and enhancing well-being in personal lives and improving productivity and relationships in the workplace.

In the East, mindfulness developed in Hindu, Buddhist, Taoist and other traditions as a component of yoga and meditation practice, designed to free the mind of unwholesome habits. In the West mindfulness is an element of many Jewish, Christian, Muslim and North American aboriginal practices designed for spiritual growth.

Over the past two decades, researchers and mental health professionals have been discovering that both ancient and modern mindfulness practices hold great promise for ameliorating virtually every kind of psychological suffering–from everyday worry, dissatisfaction and neuroticnhabits to more serious problems with anxiety, depression, substance abuse and related conditions.

Neuroscience research on mindfulness has given us another perspective. When we are mindful, the sympathetic nervous system (stress response) is kept in check and dampened, and the parasympathetic nervous system is activated, which helps us keep calm.

Mindful awareness can be developed through traditional activities such as yoga, tai chi, qigong, and prayer, all of which widens one’s awareness by focusing on body sensations or breathing. Mindfulness also focuses on expanding one’s inner awareness of experiences, emotions and thoughts, all of which contribute to greater self-awareness. With greater self-awareness comes greater objectivity. Mindfuleness focuses on the present moment rather than past or future thoughts.

What is Mindfulness?

Jon Kabat-Zinn, founder of the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, describes mindfulness as “paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment and nonjudgmentally.” Other definitions includes the qualities of compassion, acceptance and lovingkindness.”

Jon-Kabat-Zinn and others have described these elements of mindfulness:

- Paying attention: Focusing 100% of your attention on whatever you are doing at the moment.

- Non-judgment: observing impartially your experiences, without concluding they are good or bad.

- Patience: not rushing to conclusions or actions, but patiently waiting and observing things as they develop.

- Being in the present moment. Being aware of how things are right now in the present moment, not as they were in the past, or how they might be in the future.

- Non-reactivity. Our brains are built to have you react automatically, without thinking. Mindfulness encourages you to respond to your experience rather than react to your thoughts. Mindfulness is a deliberate and intentional choice.

- Beginner’s mind: observing your experiences both externally and internally as they it was the first time.

- Non-striving: not trying to force things to happened, but rather accepting whatever happens in the moment as just “is.” This is a state of non-doing.

- Acceptance: unconditionally accepting your feelings, emotions, thoughts and beliefs. Also this means understanding that these things are not facts.

- Open-mindedness-and-open-heartedness. Mindfulness is not just about the head or brain, it’s about the heart and spirit as well. To be open-hearted is to bring a quality of kindness, compassion, warmth and friendliness to our experience.

- Non-attachment: avoidance of attaching meaning to thoughts and feelings, or connecting a given thought to a feeling. Instead, let a thought or feeling come in and pass without connecting it to anything, observing them exactly as they are.

Mindfulness meditation comes in 2 distinct forms:

1. Formal meditation: This is a meditation when you intentionally take time out of your day to embark on a meditative practice.

2. Informal meditation: This is where you go into a focused and meditative state of mind as you go about your daily activities. You train your mind to stay in the present moment rather than habitually straying into the past or future. And you train your mind to notice in detail what’s going on about you.

The Benefits of Mindfulness According to Research

The National Institute of Health has funded more than 50 studies testing the potential health benefits of mindfulness techniques.

The key research findings of a number of recent significant studies have shown that regular meditation physically alters the brains of participants, and the effect lasts long after meditation periods. Research studies have shown that mindfulness meditation reduced the level of depression; reduced negative ruminative thinking; reduces stress; reduces pain intensity; reduces the body’s inflammation response; improves memory and executive brain functioning ; improves the skills of attention and focus;increases one’s capacity for creative thinking; increases one’s brain matter in the area associated with emotional regulation and response control; after taking a 9 week mindfulness training course resulted in increased compassion,and decreased worry and emotional suppression; increased subjects’ capacity for self-refection; increases emotional intelligence;enhances positive emotions, life satisfaction, increases social interconnectedness and decreases social isolation.

Mindfulness in the Workplace

Mindfulness research activity is surging within organizational science. Emerging evidence across multiple fields suggests that mindfulness is fundamentally connected to many aspects of workplace functioning and leadership behavior.

Initiatives to introduce mindfulness into the workplace, holds a promise for a cost effective way to improve employee productivity and well-being, while reducing health care costs, most of which are stress related. In my work with CEOs, senior executives, business owners and professionals, mindfulness is a key part of their leadership training and coaching experience.

Many companies such as Raytheon, Proctor and Gamble, Google, eBay, Apple, General Mills, Raytheon, Unilever, Comcast, Yahoo, Google, eBay, and professional athletic teams, the U.S. Military and scores of others have implemented mindfulness meditation programs for employees and the participants have reported a positive change in work capacity, stress management, relationships, reduced absenteeism and reduced health costs.

Green Mountain Coffee Roasters (GMCR) offers a Mindfulness Center at their facilities where employees can take year round retreats and workshops. GMCR returned roughly 3,400% in the stock market in the last decade, making it one of the best performing stocks during that period.

Research on Mindfulness Practices in the Workplace

Researchers Darren J. Good et al. considered 4,000 scientific papers on mindfulness, which documents the impact mindfulness has on workplace behaviors. Their findings, “Contemplating Mindfulness at Work(An Integrative Review)”, are published in the Journal of Management. Here are some of the conclusions and results of this research on mindfulness practices in the workplace:

1. Mindfulness has a positive impact on interpersonal behavior and the quality of work in groups, improved communication quality , including increased awareness and less evaluative judgment of others as well as better client-rated relationships.

2. Mindfulness by employees in one research study reduced rumination, and negative emotions.

3. Mindfulness improves emotional communication among workers.

4. Mindfulness improves relationships through by increasing workers’ empathy and compassion.

5. In one case study, the researchers observed improvements in team meetings, including more active listening, more collaboration, and greater respect among team members.

6. In another study in groups without formal leaders, showed better collective performance.

7. In another case study, mindfulness training of workers reduced aggressive communication among employees.

8. Mindfulness training has been found to bolster perspective-taking, which has been found helpful for negotiation.

Mindful Leadership

Most leadership books and training programs focus on how leaders can achieve more, do more, better, faster, with spectacular results. Most leadership development programs focus on how to become better at time management, goal setting, performance measures, team schedules and complex systems. All these efforts have been shown to result in incremental success at best. That’s because they are all external strategies to address the issues that are essentially internal.

Image is Open Source

The demands of leadership can produce what is known as “power stress,” which often leaves even the best leaders physically and emotionally drained. Leaders can easily find themselves moving from an “approach” orientation, where they are emotionally open, engaged and innovative, to one of “avoidance” characterized by aversion, irritability, aggression, fear and close-mindedness.

The point here is simple. Work and personal lives that build greater, resilience, well-being, success, fulfillment and happiness are not constructed from grandiose theories or plans, but through mastering internal capacity — self-awareness, self-management, constructing meaning and becoming more mindful.

While it is true that the effectiveness of leaders is determined by the results they achieve, those results are an outcome of the impact the leaders have on others. Behavior is driven by thinking and emotions. Thinking and emotions can be a result of mindfulness or mindlessness.

Neuroscience research clearly established that we act, decide and choose as a result of inner forces, often unconscious, and the brain’s reactive and protective mechanisms often rule us. Research also points to the existence of emotions being contagious and viral in the workplaces, often initiated by the emotional states of leaders.

In an article in Forbes magazine, professors Cyril Bouquet and Ben Bryant, citing the disastrous collision of two Boeing 747’s in the Canary Islands in 1977, killing 583 people, was a case of poor attention management. They argue that two kinds of attention disorders exacerbate the difficulties companies face in economic downturns. The leaders were too preoccupied with a few central signals or information; they ignore everything else.

Bouquet and Bryant contend that excessive relaxation follows sustained periods of high concentration. The authors argue that mindfulness can lessen the attention problems of fixation and relaxation.

The demands of leadership can produce what is known as “power stress,” a side effect of being in a position of power and influence that often leaves even the best leaders physically and emotionally drained. As a result, leaders can easily find themselves moving from an “approach” orientation to their work — emotionally open, engaged and innovative — to an “avoidance” orientation that is characterized by aversion, irritability, aggression, fear and close-mindedness.

If leaders believe they don’t have the time to work through all aspects of a problem they are inclined to be narrow in perspective and take cognitive shortcuts, and become more impulsive and reactive. Their actions, in effect become “mindless” and automatic.

Daniel Siegel, a neuroscientist and author of The Mindful Brain: Reflection and Attunement in the Cultivation of Well-Being, contends that a corporate culture of cognitive shortcuts results in oversimplication, curtailed curiosity, reliance on ingrained beliefs and the development of perceptional blind spots. He argues that mindfulness practices enable individuals to jettison judgment and develop more flexible feelings toward what before may have been mental events they tried to avoid, or towards which they had intense adverse reactions.

Daniel Goleman, author of Primal Leadership, and Richard Boyatzis and Ann McKee, authors of Resonant Leadership, argue that the first tasks of management have nothing to do with leading others, but in knowing deeply and managing oneself, which requires time for quiet refection.

Michael Carroll, author of The Mindful Leader, argues in his book that mindful leaders can be a powerful force in healing toxic workplace and reducing stress. In addition, in turbulent times a mindful leader can be more resilent and lead with calm and wisdom rather than impulsive ego-driven behavior.

Buddhist trained HR executive, Michael Carroll, argues that mindfulness in leaders and their organizations can:

- Heal toxic workplace cultures where anxiety and stress impede creativity and performance.

- Cultivate courage and confidence in spite of workplace di9culties in economic downturns.

- Pursue organizational goals without neglecting the here and now.

- Lead with wisdom and gentleness, not only with ambition, relentless drive and power.

- Develop innate leadership talents.

Daniel Goleman, writes in his book, Primal Leadership, “the first tasks of management has nothing to do with leading others; step one poses the challenge of knowing and managing oneself.” If leaders are constantly in the doing phase, without taking time for self-refection and mindfulness, this knowing of oneself presents a serious challenge.

There is no question that current times call for a new kind of leader, one who is a master of self rather than a controller of others; and it calls for a workplace where employees mindfully go about their work under less stress with greater productivity. Mindfulness can be a powerful force to accomplish both these ends.

Researchers have found that leaders who engage in mindfulness practices are positively associated with employees’ work-life balance, job satisfaction, citizenship behaviors, and job performance and negatively related to employee exhaustion and deviance; psychological need satisfaction mediated many of these associations.

In my book, Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces,I describe the benefits of leaders engaging in mindfulness practices.

Mindfulness practices can help leaders be more focused, observant and open to different perspectives. Paradoxically, becoming more present enables leaders to see reality more clearly and act more purposefully and with less of their own stuff getting in the way. This is one of a number of paradoxes which we often see operating in mindful leadership. It means being open to change, rather than trying to strive and force change, it means more listening and less talking. In essence, it means a balance of doing and being.

Among the reasons why many of these leaders seem to find mindfulness useful is that they can, very directly in a workshop setting or even better, over a couple of days, get an experience of being quieter and stiller, despite the chaos. Even briefly, this experience of observing their thoughts about the situation rather than being captured in them, opens up an option that wasn’t there before: that they can choose their reaction. Seemingly simple but also profound, in the short term there may be no change to what’s happening to us or around us. Mindfulness simply allows us to be with those happenings in a less reactive way.

Associated with mindfulness and its reduced reactivity, is the possibility of letting go of some things. Many leaders feel an obligation to always have the answers or obligation to shoulder the responsibilities alone, rather than admitting they don’t know or can’t do it. While these outmoded beliefs may reinforce a “hero” mentality, they are no longer useful. The thoughts of “should” an “shouldn’t” will not help a leader be more effective.

Mindfulness will help leader slow down, be more observant, and open to others’ ideas, perspectives and emotions. As the research has shown, mindfulness helps people not be victims of reactive responses, biases and stereotypes.

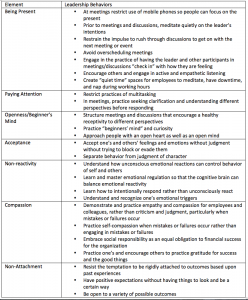

How Mindful Leaders Incorporate the Elements of Mindfulness

What Do Mindful Leaders Do Differently?

Based upon my experience in coaching senior executives in organizations combined with my examination of research, I’ve come to the following conclusions about how mindful leaders differ from other leaders. They:

- Personally engage in an in-depth process of self-awareness and self-management and encourage others to do the same.

- Learn and demonstrate a capacity for intentional response to external events rather than unconscious, “autopilot” reactivity

- Let go of their belief in themselves as technical and problem solving geniuses and embrace the notion of becoming mindful partners. This requires building an awareness of and becoming more open to nuance and subtlety

- Are open to the concept of an unknown future and uncertainty.

- Are flexible enough to make changes quickly without defending their territory or ego.

- Become skilled at leading through intuitive reflection rather than logical analysis.

- Understand what motivates other people, particularly those from different backgrounds.

- Practice attunement — listen empathetically and attentively and think about how others feel.

- Practice kindness, empathy and compassion towards others in the organization, and see these behaviors as strengths, not weaknesses.

- Develop a corporate culture that includes gratitude, and forgiveness for mistakes.

- Demonstrate a willingness to explore and express their own feelings and emotions.

- Demonstrate vulnerability as a strength.

- Are humble, rather than being driven by hubris or narcissism.

- Become more open-minded and open-hearted.

- Create a conversational space where all were welcome; all views were valued and people were free to explore.

- Are open to others’ emotions and venting without feeling threatened

- Are adept facilitators who help others gain self-awareness.

- Exhibit extraordinary curiosity and patience.

- Tolerate ambivalence, ambiguity and conflict, reduce frustration, and ward off unwholesome thoughts and feelings and resist the urge to force the situation.

- Incorporate into their working schedules substantial time for quiet reflection and a state of “being” in touch with their inner mental and emotional state, rather than the constant external state of “doing.”

- Embrace the beliefs that “less is more,” and that slowing down actually improves productivity, rather than the reverse.

- Organize workplace systems and structures to incorporate mindful practices for employees — such as meetings, “quiet time” communication systems, and conflict resolution.

- Model mindfulness practices for employees and customers to see.

Summary:

It is clear that mindfulness practices have a significant benefit for individuals in their personal lives, and there is a compelling case for the implementation of mindfulness practices and training in the workplace, and for leaders.

Read my new book, available on Amazon:Toxic Bosses: Practical Wisdom for Developing Wise, Moral and Ethical Leaders, where I examine in detail the impact that toxic bosses have on employee well-being.