By Ray Williams

May 17, 2021

In my 40 years of training, mentoring and coaching leaders I’ve found overconfidence, a critical component of a lack of self-awareness, accounts for a significant percentage of leader failures.

Overconfidence is the mother of all psychological biases. First, overconfidence is one of the largest and most ubiquitous of the many biases to which human judgment is vulnerable. For example, according to Ola Svenson’s study 93 percent of American drivers claim to be better than the median, which is statistically impossible. Similarly, a study by psychologists Patrick R. Heck and colleagues showed that 65% of Americans believe they are above average in intelligence.

In his book Investment Titans, Jonathan Burton invited readers to ask themselves the following questions: Am I better than average in getting along with people, and am I a better-than-average driver?

Burton noted that if you are like the average person, you probably answered yes to both questions. In fact, studies typically find that about 90 percent of respondents answer positively to those types of questions. Obviously, 90 percent of the population cannot be better than average in getting along with others, and 90 percent of the population cannot be better-than-average drivers.

While, by definition, only half the people can be better than average at getting along with people and only half the people can be better-than-average drivers, most people believe they are above average. The logical conclusion we can draw is that a high percentage of those self-described “above average” individuals are in fact below average in those areas. And they are blissfully unaware of their incompetence.

Another way in which people can indicate their overconfidenceabout something is by providing a 90 percent confidence interval around some estimate; when they do so, the truth often falls inside their confidence intervals less than 50 percent of the time, suggesting they did not deserve to be 90 percent confident of their accuracy. In his 2011 book, Thinking Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman called overconfidence “the most significant of the cognitive biases.” In his New York Times article, he said: “Overconfident professionals sincerely believe they have expertise, act as experts and look like experts. You will have to struggle to remind yourself that they may be in the grip of an illusion.”

The overconfidence effect is a well-established bias in which a person’s subjective confidence in his or her judgments is reliably greater than the objective accuracy of those judgments, especially when confidence is relatively high.Overconfidence is one example of a miscalibration of subjective probabilities. Throughout the research literature, overconfidence has been defined in three distinct ways: (1) overestimation of one’s actual performance; (2) overplacement of one’s performance relative to others; and (3) overprecision in expressing unwarranted certainty in the accuracy of one’s beliefs.

Overconfidence has been called the most “pervasive and potentially catastrophic” of all the cognitive biases to which human beings fall victim. It has been blamed for lawsuits, strikes, wars, and stock market bubbles and crashes.

Strikes, lawsuits, and wars could arise from overplacement. If plaintiffs and defendants were prone to believe that they were more deserving, fair, and righteous than their legal opponents, that could help account for the persistence of inefficient enduring legal disputes. If corporations and unions were prone to believe that they were stronger and more justified than the other side, that could contribute to their willingness to endure labor strikes. If nations were prone to believe that their militaries were stronger than were those of other nations, that could explain their willingness to go to war.

Overconfidence in an Organizational or Institutional Setting

Researchers A. Peter McGraw, Barbara A. Mellers and Ilan Ritov published a study “The Affective Costs of Overconfidence,” in the Journal of Behavioral Decision-Making, and concluded: “Most people view themselves through rose-colored glasses. They believe their future holds more favorable outcomes and fewer unfavorable outcomes than those of their peers. They believe they are superior to others on most socially desirable dimensions. They believe they can influence and even control situations governed largely by chance, and they believe their successes and failures are due to skill and bad luck, respectively.”

Positive illusions can have advantages, the authors argue, such as increasing motivation, raising aspiration levels, and strengthening coping mechanisms in the face of negative feedback. However, a growing literature questions the generality of the beneficial association between positive illusions and mental health. Others claim that positive illusions are disadvantageous, and even harmful, when they lead to poor judgment, disengagement, the pursuit of unreasonable goals, and suboptimal negotiations. We add to this literature by demonstrating the emotional costs of positive illusions; overly optimistic beliefs can diminish the pleasure of outcomes.

Using 10 years of quarterly CFO surveys conducted at Duke, Itzhak Ben-David, associate professor of finance at Ohio State, and professors John R. Graham and Campbell R. Harvey of Duke looked at more than 13,300 forecasts of the S&P 500 made by finance professionals. They found the range of possible outcomes that CFOs provide for where the stock market will be in one year to be unrealistically narrow.

“These executives are too sure of their ability to predict the future,” Ben-David said. “And we found this overconfidence was linked to decision-making at their firms, so there is a real-world impact.”

Confidence is arguably one of the most highly rated leadership virtues. But too much of it can be catastrophic, particularly when it comes to judgment and decision-making. Research has found that overconfident leaders can have a negative impact on organizational performance, leading to everything from introducing risky products that are unlikely to be successful to poor decisions about mergers and acquisitions.

Despite these findings, overconfident people attain higher social status and are viewed as more competent, allowing them to reap the reputational benefits. “Confidence makes individuals appear more competent in the eyes of others, even when that confidence is unjustified and unwarranted,” says Cameron Anderson from the Haas School of Management at the University of California, Berkeley. Overconfidence undeniably wields a great deal of influence.

Guts before glory may well be the mantra for some overconfident, risk-taking chief executives. The approach can bring with it innovation and drive, but it is an attitude that could also have negative consequences for their organizations.

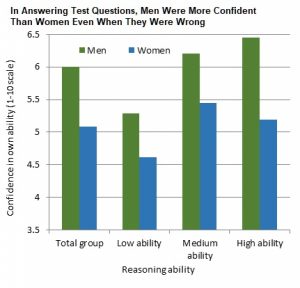

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, argues both in his book Why Do So Many Incompetent Men Become Leaders?: (And How to Fix It) and his Harvard Business Review article “How to Spot an Incompetent Leader, contends,“To start, those responsible for judging leadership candidates need to improve their ability to distinguish between confidence and competence. The one main advantage men have over women when it comes to being picked for these roles is our human tendency to equate hubris and arrogance to talent. Although it is true that all of us are generally overconfident, men tend to be more overconfident (and arrogant) than women.”

He goes on to say, “Overconfidence is the natural result of privilege. If the future of leadership were more meritocratic, and managers selected leaders on the basis of their talent and potential rather than Machiavellian self-promotion, reckless risk taking, or narcissistic delusions, we would not just end up with more women leaders, but also with better leaders. Many competent men are also overlooked for leadership roles because they don’t match our flawed leadership archetypes — meaning, they are perceived as ‘not masculine enough,’ or fail to display the very attributes that make leaders less effective.”

Across four studies, a team of Georgia-based psychological scientists Lee A. Macenczak, Stacy Campbell, Amy B. Henley, and W. Keith Campbell found a relationship between narcissism and overconfidence: Higher narcissism went hand-in-hand with overconfidence. When highly narcissistic people were primed with feelings of power, they became even more overconfident in their abilities.

“Narcissists are especially prone to errors of overconfidence because they possess the following qualities: they think they are special and unique, that they are entitled to more positive outcomes in life than are others, and that they are more intelligent and physically attractive than they are in reality,” Macenczak and colleagues explain in the journal Personality and Individual Differences.

Grandiose narcissism is characterized by an inflated sense of self-importance and entitlement, feelings of superiority over others, and a readiness to exploit others. People with these characteristics tend to make their way up the hierarchy within organizations, often ending up in positions of power.

In an international study — “Executive Overconfidence and Securities Class Actions ” — UNSW Business School senior lecturer Mark Humphery-Jenner , along with Suman Banerjee, Vikram Nanda and Mandy Tham, analyzes how CEO overconfidence can have an impact on the likelihood of a securities class action (SCA) being taken against a company.

“[During the research], executive overconfidence was routinely remarked on as being an issue of concern in relation to financial misconduct and poor financial performance,” Humphery-Jenner says. “That appears to date back to corporate scandals such as Enron [in 2001] which were, at least in part, attributed to overconfidence in addition to fraud.”

Humphery-Jenner notes that more recently, in the global financial crisis of the late 2000s, there was also a degree of audacity about the types of assets in which companies invested, leading to poor corporate performance. “Certainly when companies are failing there’s increased risk of litigation — the real issue is that to get litigation going you would have to be able to show some form of misconduct that warrants litigation and you would want the companies to have enough financing so that if you sued you could actually get the money,” he says.

Clearly, however, the repercussions for companies and executives in the face of an SCA can be serious. As the paper states: “Firms that are sued often suffer in the product market and have worse access to capital. Given the large potential cost of SCAs, it follows that executives will tend to risk SCAs only if they believe the benefits to be large or believe that their actions are unlikely to be detected and punished.”

“Results of the research show that overconfident CEOs’ firms are about 25% more likely to be subject to a securities class action than are other firms.”Mark Humphrey-Jenner argues.

Overconfidence and the Brain

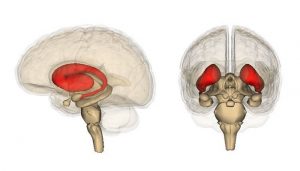

The question is, Why? According to psychologist and author, Maria Konnikova, “Human beings don’t like to exist in a state of uncertainty and ambiguity.” Confident people give off an air of assurance and certitude and are perceived as being competent which makes us an easy target to influence. In fact, emerging research has identified a particular area in the brain that responds to confidence, the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), an area involved in emotional regulation.

The link between overconfidence and poor decision making is under the spotlight in an international study by scientists from Monash University and the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig.

People vary widely in their awareness of what they do and don’t know, or metacognitive ability, and in general are too confident when evaluating their performance. This often leads to poor decision making with potentially disastrous consequences, according to the report’s authors.

The team has published a study in the journal Social,Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience which provides some insight into how overconfidence can lead to poor decision making.

The authors include an international group of scientists at the Department of Social Neuroscience at the Max Planck Institute headed by Professor Tania Singer in collaboration with Dr Pascal Molenberghs from the Monash Institute of Cognitive and Clinical Neurosciences and Fynn-Mathis Trautwein, Anne Böckler and Philipp Kanske from the Max Planck institute team.

They analyzed data from the ReSource Project, which is a unique, large scale study on Eastern and Western methods of mental training performed at the Max Planck Institute. In the context of a social cognition task performed in the brain scanner, the volunteers watched a video of a person telling a story and then had to answer a difficult question about what the person said.

Subsequently, people indicated how confident they felt their response was correct. The researchers then measured how good people were in evaluating their own accuracy; a process called metacognition.

“The more confident people were about their performance, the higher the activation in brain areas such as the striatum, an area often associated with reward processing,” first author Dr Molenberghs said.

“However, too much confidence was associated with lower metacognitive ability,”co-first author Trautwein added.

When combined, the results indicate that although being confident entails a reward-like component, it can lead to overconfidence which in turn can undermine decision making.

Read new book, available on Amazon:Toxic Bosses: Practical Wisdom for Developing Wise, Moral and Ethical Leaders, where I examine in detail the impact that toxic bosses have on employee well-being.