Are you born being self-confident, or do you learn to be that way? This question is the classic nature vs. nurture inquiry. While conventional wisdom has been on the side of nurture, there’s research that indicates some people may be genetically predisposed to be self-confident.

Intelligent children tend usually do well in school. But there are a lot of exceptions to that rule. Some young people with high IQs don’t ever become academic superstars; while those identified as less intelligent can become super successful. Some psychologists have focused on things like self-esteem and self-confidence to explain these outcomes. The assumption has been that these psychological traits are shaped mostly by good parenting—by positive beliefs and expectations and parent modeling.

However, some recent research has rekindled the debate over nature vs. nurture, indicating there may be more of a genetic determinant than we commonly think.

Definition and History of Concept of Self-Confidence

The concept of self-confidence has been defined as “self-assurance in one’s personal judgment, ability, or power.” It is a positive belief that in the future one can generally accomplish what one wishes to do. Self-confidence is not the same as self-esteem, which is an evaluation of one’s own worth, whereas self-confidence is more specifically trust in one’s ability to achieve some goal, which one meta-analysis suggested is similar to the concept of self-efficacy.

Famous psychologist Abraham Maslow and many others after him have emphasized the need to distinguish between self-confidence as a generalized personality characteristic, and self-confidence with respect to a specific task, ability or challenge (i.e. self-efficacy). Self-confidence is different from self-efficacy, which psychologist Albert Bandura has defined as a “belief in one’s ability to succeed in specific situations or accomplish a task.” Psychologists have long noted that a person can possess self-confidence that he or she can complete a specific task (self-efficacy) (e.g. cook a good meal or write a good novel) even though they may lack general self-confidence, or conversely be self-confident though they lack the self-efficacy to achieve a particular task (e.g. write a novel).

In 1890, the philosopher William James in his Principles of Psychology wrote, “Believe what is in the line of your needs, for only by such belief is the need fulfilled … Have faith that you can successfully make it, and your feet are nerved to its accomplishment,” expressing how self-confidence could be a virtue. That same year, Dr. Frederick Needham in his presidential address to the opening of the British Medical Journal’s Section of Psychology praised a progressive new architecture of an asylum accommodation for insane patients as increasing their self-confidence by offering them greater “liberty of action, extended exercise, and occupation, thus generating self-confidence and becoming, not only excellent tests of the sanity of the patient, but operating powerfully in promoting recovery.” In doing so, he seemed to early on suggest that self-confidence may bear a scientific relation to mental health.

With the arrival of World War I, psychologists praised self-confidence as being able to decrease nervous tension, allay fear, and facing the horror of the battlefield; they argued that soldiers who cultivated a strong and healthy body would also acquire greater self-confidence while fighting. At the height of the Temperance social reform movement of the 1920s, psychologists associated self-confidence in men with remaining at home and taking care of the family when they were not working. During the Great Depression, psychologists Philip Eisenberg and Paul Lazerfeld noted how a sudden negative change in one’s circumstances, especially a loss of a job, could lead to decreased self-confidence, but more commonly if the jobless person believes the fault of his unemployment is his. They also noted how if individuals do not have a job long enough, they became apathetic and lost all self-confidence.

In 1943, Abraham Maslow in his paper “A Theory of Human Motivation” argued that individuals only were motivated to acquire self-confidence (one component of “esteem”) after they individual had achieved what they needed for physiological survival, safety, and love and belonging. He claimed positive self-esteem led to feelings of self-confidence that, once attained, led to a desire for “self-actualization.” As material standards of most people rapidly rose in developed countries after World War II and fulfilled their material needs, scores of widely cited academic research about-confidence and many related concepts like self-esteem and self-efficacy emerged.

Other Theories and Research of Self-Confidence

Some studies suggest various factors within and beyond an individual’s control that affect their self-confidence. William Hippel and Robert Trivers proposed that people will deceive themselves about their own positive qualities and negative qualities of others so that they can display greater self-confidence than they might otherwise feel, thereby enabling them to advance socially and materially.

Daniel Cervone and his colleagues found that new information about an individual’s performance interacts with an individual’s prior self-confidence about their ability to perform. If that particular information is negative feedback, this may interact with a negative affective state (low self-confidence) causing the individual to become demoralized, which in turn induces a self-defeating attitude that increases the likelihood of failure.G.A. Akerlof also found that self-confidence increases a person’s general well-being and one’s motivation and therefore often performance. He also argued that self-confidence increases one’s ability to deal with stress and mental health.

A meta-analysis of 12 articles on the subject by Bernard Weiner found that generally when individuals attribute their success to a stable cause (a matter under their control) they are less likely to be confident about being successful in the future. If an individual attributes their failure to an external cause (a factor beyond their control, like a sudden and unexpected storm) they are less likely to be confident about succeeding in the future. Therefore, if an individual believes he/she failed to achieve a goal (e.g. give up smoking) because of a factor that was beyond their control, he or she is more likely to be more self-confident that he or she can achieve the goal in the future. Whether a person in making a decision seeks out additional sources of information depends on their level of self-confidence specific to that area. As the complexity of a decision increases, a person is more likely to be influenced by another person and seek out additional information.

One’s self-confidence can vary in different environments, such as at home or in school, and with respect to different types of relationships and situations. Some researchers contend the more self-confident an individual is, the less likely they are to conform to the judgments of others. Leon Festinger found that self-confidence in an individual’s ability if the individual is able to compare themselves to others who are roughly similar in a competitive environment.

Jay Conger and colleagues and Robert House and colleagues found in their research people are more likely to choose leaders with greater self-confidence than those with less self-confidence.

Individuals low in power and thus in self-confidence are more likely to use coercive methods of influence and to become personally involved while those low in self-confidence are more likely to refer problem to someone else or resort to bureaucratic procedures to influence others (e.g. appeal to organizational policies or regulations).Evidence also has suggested that women who are more self-confident may receive high performance evaluations but not be as well liked as men who engage in the same behavior.

Behavioral geneticist Corina Greven of King’s College in London and her colleague, Robert Plomin, of the Institute of Psychiatry, argue that self-confidence is more than a state of mind–but rather, is a genetic predisposition. Their research, published in the journal, Psychological Science, was a rigorous analysis of the heritability of self-confidence—and its relationship to IQ and performance.

Contrary to accepted wisdom, the researchers found that children’s’ self-confidence is heavily influenced by heredity—at least as much as IQ is. Indeed, as-yet-unidentified self-confidence genes appear to influence school performance independent of IQ genes, with shared environment having only a negligible influence. Greven and Plomin also found that children with a greater belief in their own abilities often performed better at school, even if they were actually less intelligent. They also concluded the same held true for athletes, with ability playing a lesser role than confidence. Plomin’s findings suggest that the correlation between genes and confidence may be as high as 50%, and may be even more closely correlated than the link between genes and IQ.

Katty Kay and Claire Shipman, authors of“The Confidence Code: The Science and Art of Self-Assurance — What Women Should Know argue genetics had a strong influence on an individual’s self-confidence.

Not surprisingly, intelligence is the positive attribute that has received the most attention. Researchers around the world have already uncovered at least one intelligence gene by comparing DNA and IQ scores. A young Chinese researcher, Zhao Bowen, is looking for another one, his sequencing machine is on overdrive, going through DNA samples from the world’s smartest people.

The Arguments Against the Nature (Genetic) Perspective

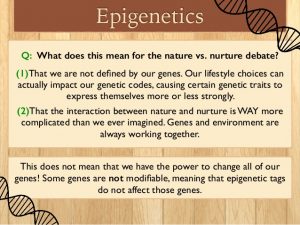

Some researchers would argue that our genes are not under the complete mercy of nurture. Enter the field of epigenetics. As we grow older, hereditary dominances start to decrease, according to researchers Daniel M. Dick and his colleagues. That is — over time, nurture takes over nature, including in shaping our self-worth.

In terms of numbers, per one longitudinal study on twins, genes contributed 62% to the levels of self-esteem in 14-year old boys and 40% in 17-year olds, while for girls these percentages were 40% and 29%. Later on in life, it gets even better. Another study by S. McGuire and colleagues discovered that the nature effect was 40%, but nurture was responsible for 60% of our overall confidence.

Despite popular views women, are not completely at a disadvantage when it comes to self-confidence. Men may be more positive in their self-opinions, but their genes influence these views to a much greater degree. For women, it tends to be a blend of nature and nurture that shapes their sense of worth.

Woman Looking at Reflection — Image by © Elisa Lazo de Valdez/Corbis

Self-Confidence and Leadership

Great leaders are not made, they’re born. At least, that’s what some people think.

Claims that the best leaders simply have brains that are “wired differently to most” are common, dismissing the notion that the skills can be taught. A studyby Jan-Emmanuel De Neve and colleagues at University College London, Harvard University, New York University and the University of California concluded that “leadership is partly hereditary,” and going on to say

“The results we report here suggest that what determines whether people occupy leadership positions may be a complex product of genetic and environmental influences.”

A recent studyby H. Hannah from Wake University found that there are neurological differences in the brains of people who had been identified as leaders. This type of research may make it possible to identify future leadership candidates through brain scans.

Richard D. Arvey, Maria Rotundo, Wendy Johnson, Zhen Zhang, Matt McGuev conducted a study to investigate the influence of genetic factors and personality on leadership role among a sample of 238 male twins. Results indicated that 30% of the variance in leadership role occupancy could be accounted for by genetic factor, while non-shared (or non-common) environmental factor accounted for the remaining variance in leadership role occupancy. Genetic influences also contributed to personality variables known to be associated with leadership (i.e., social potency and achievement).

So What Is the Answer?

In balance though, the vast majority of research studies support the notion that leadership is largely derived from nurture, from experience and situation, training and personal growth and development. Experts say the reality is much more complicated than newspaper headlines make out. UCL’s report itself acknowledges: “What determines whether an individual occupies a leadership position is the complex product of genetic and environmental influences.” And while papers claim that the study proves leaders such as Churchill or Thatcher were born great, the report’s lead author actually said: “The conventional wisdom – that leadership is a skill – remains largely true”.

For leaders themselves, the misconception that they are in their position because of their natural genetic code could be disastrous. Arrogant and over-confident managers may think they do not need training or experience to become a good leader.

As genetic research progresses and we understand more about brain functioning in the future, it will be interesting to see if any proactive measures are taken to screen potential leaders early in their lives, and subsequently provide extensive training (nurturing) for them. The big questions have now shifted away from whether certain personality traits are genetic or not, and toward figuring out how much exactly our specific environments influence our genes and vice versa.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.