By Ray Williams

October 21, 2020

“I’ll never get that promotion/job. I screwed up again. I should/shouldn’t have…(fill in the blanks).

We frequently hear people verbalize these types of self-critiques to their friends, families and even strangers online. Or you may do it too.

We can define self-criticism as “an intense and persistent relationship with the self, characterized by (1) an uncompromising demand for high standards in performance, and (2) an expression of hostility and derogation toward the self when these high standards are – inevitably – not met.”

Many of us believe that being self-critical is the best way to improve and achieve success or happiness. Sometimes that can appear as perfectionism, and when the perfect result doesn’t materialize we criticize ourselves. And sometimes it can appear as guilt, shame or depression.

In such a hyper-connected, self-obsessed society, this tendency toward self-judgment can be hard to escape — especially for women. In fact, a new national online survey by TODAY and AOL found that 60 percent of adult women have negative thoughts about themselves on a weekly basis.

Under distress, this self-criticism heightens. The TODAY/AOL survey also found that as times get tough and people become upset, women are far more likely than men to respond with self-criticism.

As the chart shows, a majority of women — 52 percent — admit that they are hard on themselves when they are upset. Yet, women are also more likely than men to share their pain with others, an act that vulnerability researcher Dr. Brené Brown says takes true courage.

What Does Research Tell Us About Self-Criticism

Researcher Dr. Kelly McGonigal at Stamford University has found that self-criticism is actually far more destructive than it is helpful. For example, in one set of studies that followed hundreds of people trying to meet a wide range of goals – from losing to weight to pursuing academic goals, improving social relationships or their performance – the researchers found that the more people criticized themselves, the slower their progress over time and the less likely they were to achieve the goal they’d set.

In fact, neuroscientists suggest self-criticism actually shifts the brain into a state of self-inhibition and self-punishment that causes us to disengage from our goals. Leaving us feeling threatened and demoralized, it seems to put the brakes on us taking action, and leaves us stuck in a cycle of rumination, procrastination and self-loathing.

Research by psychologists Ricks Warren, Elke Smeets and Kristin Neff published in Current Psychiatry, shows that “although most people engage in self-criticism when they believe they have failed or engaged in behavior for which they have regrets, research has shown that self-compassion is a robust resilience factor when faced with feelings of personal inadequacy. ”Although self-criticism is destructive across clinical disorders and interpersonal relationships, self-compassion is associated with healthy relationships, emotional well-being, and better treatment outcomes,” the researchers argue.

Self-critical individuals experience feelings of unworthiness, inferiority, failure, and guilt. They engage in constant and harsh self- scrutiny and evaluation, and fear being disapproved and criticized and losing the approval and acceptance of others. Although self-criticism is the aspect of perfectionism most associated with maladjustment,one can be harshly self-critical without being a perfectionist. Most studies of self-criticism have not measured shame. However, this self-conscious emotion has been implicated in diverse forms of psychopathology.In contrast to guilt, which results from acknowledging bad behavior, shame results from seeing oneself as a bad or inadequate person.

Several studies have found that self- criticism predicts depression. Self-criticism has been shown to predict depressive relapse and residual self-devaluative symptoms in recovered depressed patients.In one study, currently depressed and remitted depressed patients had higher self-criticism and lower self- compassion compared with healthy controls.

Self-criticism is common across psychiatric disorders. In a study of 5,877 respondents in the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), self-criticism was associated with social phobia, findings that were significant after controlling for current emotional distress, neuroticism, and lifetime history of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders.Further, in a CBT treatment study, baseline self-criticism was associated with severity of social phobia and changes in self- criticism predicted treatment outcome.Self-criticism might be an important core psychological process in the development, maintenance, and course of social phobia. Patients with social anxiety disorder have less self-compassion than healthy controls and greater fear of negative evaluation.

Self-criticism is correlated with eating disorder severity.In a study of patients with binge eating disorder, researchers found that self-criticism was associated with the over-evaluation of shape and weight independently of self-esteem and depression. Self-criticism also is associated with body dissatisfaction, independent of self-esteem and depression. Numerous studies have shown that shame is associated with more severe eating disorder pathology.

Several studies have shown that self- criticism has negative effects on interpersonal relationships throughout life:

- Self-criticism at age 12 predicted less involvement in high school activities and, at age 31, personal and social maladjustment.

- High school students with high self- criticism reported more interpersonal problems.

- Self-criticism was associated with loneliness, depression, and lack of intimacy with opposite sex friends or partners during the transition to college.

- In a study of college roommates,self- criticism was associated with increased likelihood of rejection.

- Self- criticism was associated with marital dissatisfaction and depression.

- Self-critical mothers with postpartum depression were less satisfied with social support and were more vulnerable to depression.

Research suggests that self-critics approach goals based on motivation to avoid failure and disapproval, rather than on intrinsic interest and personal meaning. In studies of college students pursuing academic, social, or weight loss goals, self-criticism was associated with less progress to that goal. Self-criticism was associated with rumination and procrastination, which the researchers suggest might have focused the self-critic on potential failure, negative evaluation from others, and loss of self-esteem. Additional studies showed the deleterious effects of self-criticism on college students’ progress on obtaining academic or music performance goals and on community residents’ weight loss goals.

Studies have explored the impact of early relationships with parents and development of self-criticism. Parental overcontrol and restrictiveness and lack of warmth consistently have been identified as parenting styles associated with development of self-criticism in children.One study found that self-criticism fully mediated the relationship between childhood verbal abuse from parents and depression and anxiety in adulthood.Reports from parents on their current parenting styles are consistent with these studies.One research study concluded: “[s]elf-critics’ negative childhood experiences thus seem to contribute to a pattern of entering, creating, or manipulating subsequent interpersonal environments in ways that perpetuate their negative self-image and increase vulnerability to depression.” Not surprisingly, self-criticism is associated with a fearful avoidant attachment style. Review of the developmental origins of self-criticism confirms these factors and presents findings that peer relationships also are important factors in the development of self-criticism.

The Critical Inner Voice (or Gremlin)

We all have a “critical inner voice,” which acts like a cruel coach inside our heads that tells us we are worthless or undeserving of happiness. This coach is shaped from painful childhood experiences and critical attitudes we were exposed to early in life as well as feelings our parents had about themselves. While these attitudes can be hurtful,and over time, they can become engrained in us. As adults, we may fail to see them as an enemy, instead accepting their destructive point of view as our own.

We can self-sabotage in order to remain in familiar psychological territory. Over many years, feelings of rejection, self-deprivation and oppression can become like an old, comfortable pair of shoes. Negativity becomes an emotional default of sorts and is quite difficult to escape. Worse, most often the familiar inner negativity is repressed and seeks expression on autopilot. Thus, the compulsion to self-criticize or perform any number of self-sabotaging acts. Overcoming self-sabotage requires expanded self-awareness, as well as the mental vocabulary required to define just what’s really going on.

There are countless quotes, mantras and entire philosophies dedicated to telling us to find and follow our “inner voice.” However, the inner voice can be tricky. Like pretty much everything and everyone in our lives, it has two sides. In fact, it’s almost as if we’re in possession of two inner voices: a positive life-affirming voice one that represents our real self (our true wants, desires and goals) and a critical, coaxing and destructive inner voice.

Getting to know and challenge this “voice” is one of the most essential psychological hurdles we can overcome in striving to live our version of our best life. For our real self to win out over our anti-self, we have to understand how our inner voices operate. Where do they come from? What’s their purpose? How can we tap into our real, positive sense of self, while quieting our critical inner voice?

We can start by understanding one major concept: we are, in many ways, ruled by our past. From the moment we’re born, we absorb the world around us. The early attitudes, beliefs and behaviors we were exposed to can become an inner dialogue, affecting how we see ourselves and others. For example, the positive behavior and qualities our parents or early caretakers had helped us form a positive sense of self as well as many of our values. If we felt love, acceptance or compassion directed toward us, this nurtured our real self and the positive feelings we have about who we are in the world. However, the critical attitudes and negative experiences we withstood formed and fueled our anti-self. Early rejections and harmful ways of relating affect a child’s budding self-perception, not to mention their point of view toward other people and relationships in general. These impressions become the voices in our heads.

No parent, or person for that matter, is perfect. We have inevitably been influenced by both the strengths and weaknesses our primary caretakers brought to the table. However, we’re not doomed to repeat their mistakes or blindly accept the beliefs we have about ourselves based on our early lives. In fact, we can constantly find ways to differentiate ourselves, connecting with the good but separating ourselves from the attitudes and beliefs that no longer serve us in the present. An important first step in this process is to take on the critical inner voice. When we come to know how this voice is harmfully shaping our present perceptions, emotions and actions, we can learn to regard it as more of an external enemy than our true point of view.

The Hazards of Self-Criticism

Many think self-criticism is a good thing and helpful. We view this traitas a strong testimony for scrupulousness, honesty, responsibility, and integrity, four highly coveted moral virtues. We also deem self-criticism as a pre-condition for self-improvement and growth. “It is only when we courageously look inside and identify our flaw and own them, that we can begin the journey of correcting – or at least minimizing – them, thereby becoming better persons”, is what many of us tell ourselves.

However, research suggests that self-criticism is highly likely to involve a quality of self-bashing, and when it does, its adverse effects on our physical and mental health are formidable. Most of the research is summarized in the book “Erosion: The Psychopathology of Self-criticism” .

Signs You Are Too Self-Critical

Most of us consciously aspire to be the best we can and to do the right thing, and self-analysis can serve us as a tool for measuring our efforts and achievements.

While analysis is a healthy way to observe our own behavior and learn how to overcome weaknesses and bad habits, it often transforms into self-devaluation.

- You blame yourself for every negative situation.You feel you are personally responsible when bad things happen, too quick to take all the blame, while ignoring legitimate outside factors. Some people can take this tendency to an extreme. For example, blaming yourself for planning an event on a day it happens to rain.

- You’re down on yourself as a whole person, as opposed to specific mistakes you may make. Instead of saying: “This was the wrong way to do that, next time I might try…” You tend to diminish yourself with: I am a failure. This way you do not focus on the behavior that caused the problem and what can be improved. Rather, you apply negative thoughts to your personality and undermine your confidence in general.

- You often avoid taking risks.You tell yourself are going to fail, because it happens every time, right? Therefore, you end up convinced that the safest course of action is no action at all.

- You often avoid expressing your own opinion.What if you say something stupid? Perhaps you think you are boring, or not informed enough to debate with certain company. It’s smart not to stand out as informed when you know very little about a specific subject, but if you behave the same way in the company of people who are of equal or even lesser knowledge, then you are probably engaged in self-criticism when you force yourself to hold back.

- You often compare yourself to someone else – and typically come up short. In this case your self-esteem depends on how (you believe) other people stack up against you, which may be beneficial if they are less informed or less skilled. Yet, when you are the less informed or less skilled, your self-criticism amplifies. You may also have a tendency to see others as globally better than you. If this is the case, you’re going to end up feeling less than, guaranteed.

- You are never satisfied with achievements. Whatever you do, you find nagging flaws. You may believe that if you can’t do something right, you shouldn’t do it at all. However, you are prone to harp on inevitable flaws even when your results are positive.

- You have impossibly-high standards. Do you believe you cannot be happy if you are not highly intelligent, highly attractive, wealthy and super creative? Yet, are your standards impossible to satisfy? This is a variation on #6 above, where we position ourselves to be dissatisfied. You can know if your standards are too high if the results you produce rarely, if ever, match the image in your head. If they don’t you are likely to self-criticize.

- Worry and ‘what if’ scenarios…You foresee the worst scenario of what may happen and obsess about it. Yes, worry can be a form of self-doubt and self-criticism, especially when you worry incessantly about personal failure and the humiliation hat you foresee.

- You never ask for help.If asking for help is a major ordeal for you, then you may be self-critical, afraid of appearing weak or inept. Why would you be afraid of appearing less than just because you need help? Chances are, under the surface, you’re criticizing yourself.

- You do not assert your needs and desires.Self-critical people often fears elf-assertion, as it may lead to rejection. If you speak your mind, state your needs or ask for what you want, there is always a chance you will be denied. And that can hurt. This is just life. An overly self-critical person, however, is so convinced of the pending rejection that they often accept it ahead of time and skip the self-assertion.

- You had chronically criticizing parents or caregivers or teachers. Have you been treated with negative criticism by one or both of your parents? Or your elementary school teacher? If so, you may have assimilated those messages and developed your own inner critic.

- You persist in analyzing mistakes. How often and how long do you think about the mistakes you’ve made? Do you invest enormous time and energy in analyzing what went wrong and how you are responsible for it? If you analyze mistakes past the point of learning something valuable, then you’re probably punishing yourself unnecessarily.

- You don’t forgive easily. Forgiving self and others requires letting go of criticism. If you’re bogged down in self-criticism, it will be that much more difficult to let go. Even when you’re blaming yourself, you’ll find it much more difficult to forgive others their part in life’s mishaps and misunderstandings.

- You don’t give yourself compliments.You don’t see a reason to boost your self esteem with positive messages like: I am good. I can do it. I can handle this. For some of us, talking to ourselves positively may even seem strange or ridiculous. This is a sign of chronic self-criticism.

- You get defensive in the face of feedback.Do you tend to get hurt and angry when people give you justified or constructive criticism? If you’re harboring deep self-criticism, you might overreact to others’ feedback and take things personally.

- You can’t accept compliments.When someone says something nice about you, do you feel you deserve it? Do tend you deflect compliments with self-deprecation? If so, you may be favoring a self-critical view of yourself. Hint: When someone compliments you, it’s OK to reply with simple “thank you”.

- You think within a system of black & white values.If you do not accept that there are many values between the extremes, everything is either good or bad. Setting absolute ideals leads you to ignore partial successes and give yourself credit for smaller accomplishments.

- Your achievements in life have chronically fallen beneath your capabilities.A classic sign of chronic self-criticism is under performance. After years of doing less than your best, you may look around and be disappointed at how far you’ve gotten in life. If this isn’t a call to deal with your tendency to self-criticize, nothing is!

Challenging the Inner Critic Voice

We can challenge the inner critic and begin to see ourselves for who we really are, rather than taking on its negative point of view about ourselves. We can differentiate from the ways we were seen in our family of origin and begin to understand and appreciate our own feelings, thoughts, desires and values.

There are several steps to this process:

- Notice this voice –People often listen to their critical inner voice without realizing it. It comes through almost as background noise, so they just accept much of its commentary as reality. It’s important to become more conscious of the moments when your critical inner voice starts nagging at you. Try to notice when its undermining insults and instructions chime in throughout the day. “You look so tired/fat/ugly/stupid.” “You’re annoying people.” “You can’t do this.” “You’re such a mess.” “What’s the matter with you?” It’s worth noting that this voice can be really mean, but it can also sometimes sound almost friendly and soothing. “Just stay home. You don’t need to worry about seeing anyone tonight.” Then, the minute you listen to its instructions, it starts to take the upper hand. “Alone again? You’re such a loser.” Don’t be fooled by the voice. Whether it sounds gentle or harsh, its main objective is to bring you down, to take you back to an old, familiar sense of your identity that continues to limit you.

- Write your “voices” down in the second person. A powerful exercise you can do on your own is to write down the negative thoughts you have toward yourself. First, write them down in the first person as “I” statements, i.e. “I’m not fun. No one finds me ” Then, next to each of these “voices,” write the same thoughts as “you” statements. “You’re not fun. No one finds you interesting.” This process helps you start to separate your critical inner voice from your real point of view, so you can see it as the enemy it actually is.

- Think about what or who these voices sound like. Usually when you start to list your negative thoughts, more and more tend to spill out. As this happens, especially when you switch these thoughts to the second person, these voices can start to sound familiar, like they actually come from someone else. Almost every person I’ve ever worked with has made a connection between their voices and someone from their past. They often remark, “I felt like it was my mother talking to me” or “that expression is exactly what my father used to say.” When you make these connections, you can start to piece together where your voices originated and separate them from your current sense of self.

- Challenge your critical inner voice. It’s very important when you write down your voices not to let your self-hating or self-shaming thoughts take over. The fourth and perhaps most essential step is, therefore, to respond to these statements from a realistic and compassionate perspective. Write down a more caring and honest response to each of your critical inner voice attacks. This time, use “I” statements. “I am a worthy person with many fun-loving qualities. I have a lot to offer.” As you do this exercise, be diligent in shutting out any rebuttals your inner critic tries to sneak in. Make a commitment to keep writing about yourself with the respect and regard you would have for a friend.

- Connect your voices to your actions. Your critical inner voice has plenty of bad advice to dish out. “Don’t ask her out. She’ll just reject you.” “Don’t speak up. No one wants to hear what you have to say.” “Forget about relationships. He doesn’t really love you.” “Have another piece of cake. Who cares if you’re healthy?” These statements can come through loud and clear, or they can be more subtle and suggestive. As you get better at recognizing your critical inner voice, you can start to catch on when it’s starting to influence your behavior. Did you all of a sudden shut down emotionally? Get quiet? Push away a loved one? Lash out at a friend? Try to think of the events that trigger your voices and how these voices, in turn, affect your actions. Try to identify patterns and recognize self-limiting behaviors you engage in based on these voices.

- Alter your behavior. Once you see how your inner critic can throw you off course and change your behavior, you can start to consciously act against its directives. This will likely make you uncomfortable at first. The process of tuning out your inner critic and tapping into your real self can be uplifting, but it can also cause you a lot of anxiety. These are deep-seated beliefs you’re challenging, and at first, the critical inner voice will often get louder. However, the more you actively ignore it, the weaker it will ultimately become.

Throughout the entire process of disempowering this internal enemy, there is one thing we need to practice as an opposite action that will strengthen our real self, and that is self-compassion. As researcher Dr. Kristin Neff emphasizes, unlike, self-esteem, which still lends itself to comparisons and evaluation, self-compassion focuses on self-kindness and acceptance over self-judgment. It offers a gentle way to guide ourselves back to who we really are and what we seek to be. By challenging our self-shame and cultivating our self-compassion, we establish a much stronger, more reliable view of ourselves. This point of view is not shaped by the limitations of our past but the true essence of who we are in the present and what we want for our future.

Self-Compassion

Research has shown that humans’ capacity for compassion, empathy and kindness is hardwired into our biological system, going back thousands of years.

Compassion can be defined as “a sensitivity to suffering in ourselves and others with desires to alleviate and prevent suffering.” Psychologist Kirsten Neff describes self-compassion as “an emotionally positive self attitude that [can] protect against the negative consequences of self-judgment, isolation, and rumination (such as depression).

Self-compassion has been considered to resemble Carl Rogers’ notion of “unconditional positive regard” applied both towards clients and oneself; Albert Ellis’ “unconditional self-acceptance”; Maryhelen Snyder’s notion of an “internal empathizer” that explored one’s own experience with “curiosity and compassion”; Ann Weiser Cornell’s notion of a gentle, allowing relationship with all parts of one’s being; and Judith Jordan’s concept of self-empathy, which implies acceptance, care and empathy towards the self.

Self-compassion is different from self-pity, a state of mind or emotional response of a person believing to be a victim and lacking the confidence and competence to cope with an adverse situation.

Self-compassion involves acting the same way towards yourself when you are having a difficult time, fail, or notice something you don’t like about yourself. Instead of just ignoring your pain with a “stiff upper lip” mentality, you stop to tell yourself “this is really difficult right now,” how can I comfort and care for myself in this moment? Instead of mercilessly judging and criticizing yourself for various inadequacies or shortcomings, self-compassion means you are kind and understanding when confronted with personal failings – after all, who ever said you were supposed to be perfect?

Self-compassion also requires taking a balanced approach to our negative emotions so that feelings are neither suppressed nor exaggerated. This equilibrated stance stems from the process of relating personal experiences to those of others who are also suffering, thus putting our own situation into a larger perspective.

Self-compassionate people recognize that being imperfect, failing, and experiencing life difficulties is inevitable, so they tend to be gentle with themselves when confronted with painful experiences rather than getting angry when life falls short of set ideals. People cannot always be or get exactly what they want. When this reality is denied or fought against suffering increases in the form of stress, frustration and self-criticism. When this reality is accepted with sympathy and kindness, greater emotional equanimity is experienced.

Self-compassion also requires taking a balanced approach to our negative emotions so that feelings are neither suppressed nor exaggerated. This equilibrated stance stems from the process of relating personal experiences to those of others who are also suffering, thus putting our own situation into a larger perspective. It also stems from the willingness to observe our negative thoughts and emotions with openness and clarity, so that they are held in mindful awareness.

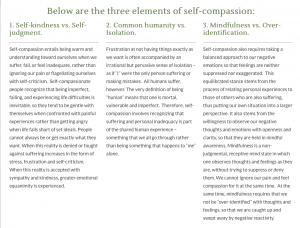

According to researcher and expert on the topic of self-compassion, Kristen Neff, there are three elements of self-compassion:

- Self-kindness. Self-compassion entails being warm and understanding toward ourselves when we suffer, fail, or feel inadequate, rather than ignoring our pain or flagellating ourselves with self-criticism. Self-compassionate people recognize that being imperfect, failing, and experiencing life difficulties is inevitable, so they tend to be gentle with themselves when confronted with painful experiences rather than getting angry when life falls short of set ideals. People cannot always be or get exactly what they want. When this reality is denied or resisted, suffering increases in the form of stress, frustration and self-criticism. When this reality is accepted with sympathy and kindness, greater emotional equanimity is experienced.

- Common humanity.Frustration at not having things exactly as we want is often accompanied by an irrational but pervasive sense of isolation – as if “I” were the only person suffering or making mistakes. All humans suffer, however. The very definition of being “human” means that one is mortal, vulnerable and imperfect. Therefore, self-compassion involves recognizing that suffering and personal inadequacy is part of the shared human experience – something that we all go through rather than being something that happens to “me” alone. It also means recognizing that personal thoughts, feelings and actions are impacted by “external” factors such as parenting history, culture, genetic and environmental conditions, as well as the behavior and expectations of others. Thich Nhat Hahn calls the intricate web of reciprocal cause and effect in which we are all imbedded “interbeing.” Recognizing our essential interbeing allows us to be less judgmental about our personal failings. After all, if we had full control over our behavior, how many people would consciously choose to have anger issues, addiction issues, debilitating social anxiety, eating disorders, and so on? Many aspects of ourselves and the circumstances of our lives are not of our choosing, but instead stem from innumerable factors (genetic and/or environmental) that we have little control over. By recognizing our essential interdependence, therefore, failings and life difficulties do not have to be taken so personally, but can be acknowledged with non-judgmental compassion and understanding.

- Mindfulness.Self-compassion also requires taking a balanced approach to our negative emotions so that feelings are neither suppressed nor exaggerated. This equilibrated stance stems from the process of relating personal experiences to those of others who are also suffering, thus putting our own situation into a larger perspective. It also stems from the willingness to observe our negative thoughts and emotions with openness and clarity, so that they are held in mindful awareness. Mindfulness is a non-judgmental, receptive mind state in which one observes thoughts and feelings as they are, without trying to suppress or deny them. We cannot ignore our pain and feel compassion for it at the same time. At the same time, mindfulness requires that we not be “over-identified” with thoughts and feelings, so that we are caught up and swept away by negative reactivity.

Self-compassion also requires taking a balanced approach to our negative emotions so that feelings are neither suppressed nor exaggerated. This equilibrated stance stems from the process of relating personal experiences to those of others who are also suffering, thus putting our own situation into a larger perspective. It also stems from the willingness to observe our negative thoughts and emotions with openness and clarity, so that they are held in mindful awareness. Mindfulness is a non-judgmental, receptive mind state in which one observes thoughts and feelings as they are, without trying to suppress or deny them. We cannot ignore our pain and feel compassion for it at the same time. At the same time, mindfulness requires that we not be “over-identified” with thoughts and feelings, so that we are caught up and swept away by negative reactivity.

Research on Self-Compassion

Self-compassion appears to enhance interpersonal relationships. In a study of heterosexual couples,self-compassionate individuals were described by their partners as being more emotionally connected, as well as accepting and supporting autonomy, while being less detached, controlling, and verbally or physically aggressive than those lacking self-compassion. Because self-compassionate people give themselves care and support, they seem to have more emotional resources available to give to others.

Self-compassion is a robust resilience factor when faced with feelings of personal inadequacy. Self-critical individuals experience feelings of unworthiness, inferiority, failure, and guilt. They engage in constant and harsh self- scrutiny and evaluation, and fear being disapproved and criticized and losing the approval and acceptance of others.Self-compassion involves treating oneself with care and concern when confronted with personal inadequacies, mistakes, failures, and painful life situations.

Self-compassion could be a protective factor for post traumatic syndrome disorder. Combat veterans with higher levels of self-compassion showed lower levels of psychopathology, better functioning in daily life, and fewer symptoms of post traumatic stress.In fact, self-compassion has been found to be a stronger predictor of PTSD than level of combat exposur

Researchers found that self-compassion was lower in generalized anxiety disorder patients compared with healthy controls with elevated stress. Low self-compassion has been associated with severity of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Self-compassion seems to buffer against body image concerns. It is associated with less body dissatisfaction, body preoccupation, and weight worries,greater body appreciation and less disordered eating.Early decreases in shame during eating disorder treatment was associated with more rapid reduction in eating disorder symptoms.

Self-compassion also is associated with intrinsic motivation, goals based on mastery rather than performance, and less fear of academic failure.

Early positive relationships with care-givers are associated with self-compassion. Recollections of maternal support are correlated with self-compassion and secure attachment styles in adolescents and adults. Researchers found that retrospective reports of parental rejection, over- protection, and low parental warmth was associated with low self-compassion.

A growing body of research suggests that self-compassion is strongly linked to mental health. Greater self-compassion consistently has been associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety,with a large effect size. Of course, central to self- compassion is the lack of self-criticism, but self-compassion still protects against anxiety and depression when controlling for self-criticism and negative affect.Self-compassion is a strong predictor of symptom severity and quality of life among individuals with anxious distress.

The benefits of self-compassion stem partly from a greater ability to cope with negative emotions. Self-compassionate people are less likely to ruminate on their negative thoughts and emotions or suppress them,which helps to explain why self-compassion is a negative predictor of depression.

Self-compassion also enhances positive mind states. A number of studies have found links between self-compassion and positive psychological qualities, such as happiness, optimism, wisdom, curiosity, and exploration, and personal initiative.By embracing one’s suffering with compassion, negative states are ameliorated when positive emotions of kindness, connectedness, and mindful presence are generated.

Self-compassion appears to provide emotional resilience over and above that attributable to self-esteem. For example, when controlling for self-esteem, self-compassion is still a robust (negative) predictor of depression and anxiety, and of happiness, optimism and positive affect. And while high self-esteem depends on successful performances and positive self-evaluations, self-compassion is relevant precisely when self-esteem tends to falter – when one fails or feels inadequate.

One study suggests that self-compassion enables people to admit and accept that there are negative as well as positive aspects of their personality.The maintenance of high self-esteem is more dependent on positive self-evaluations, and therefore may lead to cognitive distortions in order to preserve positive self-views.

In a survey involving a large community sample in the Netherlands, self-compassion was shown to be a stronger predictor of healthy functioning than self-esteem. Self-compassion was associated with more stability in feelings of self-worth over an eight-month period (assessed 12 different times) than trait self-esteem. This may be related to the fact that self-compassion was also found to be less contingent on things like physical attractiveness or successful performances than self-esteem. Results indicated that self-compassion was associated with lower levels of social comparison, public self-consciousness, self-rumination, anger and need for cognitive closure than self-esteem. In sum, self-compassion is a healthier way of feeling good about oneself than self-esteem that is based on the need to feel better than others

Misconceptions about self-compassion

A common misconception is that abandoning self-criticism in favor of self-compassion will undermine motivation. Research indicates the opposite. Although self-compassion is negatively associated with maladaptive perfectionism, it is not correlated with self-adopted performance standards.Self-compassionate people have less fear of failure and, when they do fail, they are more likely to try again.Researchersfound in a series of experimental studies that engendering feelings of self-compassion for personal weaknesses, failures, and past transgressions resulted in more motivation to change, to try harder to learn, and to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Another common misunderstanding is that self-compassion is a weakness. In fact, research suggests that self-compassion is a powerful way to cope with life challenges.There may be physiological processes underlying the buffering effects of self-compassion. Researchers found that an exercise designed to increase feelings of self-compassion reduced levels of the stress hormone cortisol and increased heart-rate variability, which is associated with a greater ability to regulate emotions (e.g., self-soothing when stressed). Interestingly, although self-compassionate people are less likely to be overwhelmed by negative emotions, they’re also more willing to experience difficult feelings and to acknowledge them as valid and important. The beauty of self-compassion is that instead of replacing negative feelings with positive ones, new positive emotions of care and connectedness are generated by embracing the negative ones, so that both are experienced simultaneously. Not surprisingly, then, self-compassion is also strongly linked to positive emotions like happiness, satisfaction with life, optimism, curiosity, enthusiasm, interest, inspiration and excitement.

Self-compassion is not self-pity. When individuals feel self-pity, they become immersed in their own problems and forget that others have similar problems. They ignore their interconnections with others, and instead feel that they are the only ones in the world who are suffering. Self-pity tends to emphasize egocentric feelings of separation from others and exaggerate the extent of personal suffering. Self-compassion, on the other hand, allows one to see the related experiences of self and other without these feelings of isolation and disconnection.

Also, self-pitying individuals often become carried away with and wrapped up in their own emotional drama. They cannot step back from their situation and adopt a more balanced or objective perspective. In contrast, by taking the perspective of a compassionate other towards oneself, “mental space” is provided to recognize the broader human context of one’s experience and to put things in greater perspective. (“Yes it is very difficult what I’m going through right now, but there are many other people who are experiencing much greater suffering. Perhaps this isn’t worth getting quite so upset about…”).

Self-compassion versus self-esteem

Although self-compassion may seem similar to self-esteem, they are different in many ways. Self-esteem refers to our sense of self-worth, perceived value, or how much we like ourselves. While there is little doubt that low self-esteem is problematic and often leads to depression and lack of motivation, trying to have higher self-esteem can also be problematic. In modern Western culture, self-esteem is often based on how much we are different from others, how much we stand out or are special. It is not okay to be average, we have to feel above average to feel good about ourselves.

This means that attempts to raise self-esteem may result in narcissistic, self-absorbed behavior, or lead us to put others down in order to feel better about ourselves. We also tend to get angry and aggressive towards those who have said or done anything that potentially makes us feel bad about ourselves. The need for high self-esteem may encourage us to ignore, distort or hide personal shortcomings so that we can’t see ourselves clearly and accurately. Finally, our self-esteem is often contingent on our latest success or failure, meaning that our self-esteem fluctuates depending on ever-changing circumstances.

In contrast to self-esteem, self-compassion is not based on self-evaluations. People feel compassion for themselves because all human beings deserve compassion and understanding, not because they possess some particular set of traits (pretty, smart, talented, and so on).

This means that with self-compassion, you don’t have to feel better than others to feel good about yourself. Self-compassion also allows for greater self-clarity, because personal failings can be acknowledged with kindness and do not need to be hidden. Moreover, self-compassion isn’t dependent on external circumstances, it’s always available – especially when you fall flat on your face! Research indicates that in comparison to self-esteem, self-compassion is associated with greater emotional resilience, more accurate self-concepts, more caring relationship behavior, as well as less narcissism and reactive anger.

The Art of Emotional Balance

When you think of models of compassion throughout time, what emotional state do you picture them in? Do you picture Mahatma Gandhi, Mother Theresa or Jesus Christ in a fiery rage, deep shame or uncontrollable sorrow over all the suffering in the world? Do you picture them with excessive warm and fuzzy feelings towards oppressors or persecutors to whom they still offer compassion? Or do you picture them with some measure of equanimity and emotional balance, even while taking action in the face of great suffering?

As its Latin root movere (to move) suggests, emotion can serve as a powerful motivator, propelling individuals towards certain action tendencies. Fear motivates organisms to run from threats, anger to attack and defend oneself, pleasure to approach. In fact, much of the literature on emotion and motivation is based on the assumption that emotions are motivating, and as a corollary to this, that more intense emotions are more strongly motivating. Intriguingly, the link between emotion and compassion appears to operate differently.

That is, research is increasingly pointing towards a Goldilocks relationship: compassion flourishes in emotional conditions characterized by not too much and not too little, not too hot and not too cold, but a temperature just right, à la emotional balance. In this chapter, we discuss the theoretical and empirical basis for understanding compassion as a motivation rather than an emotion, and subsequently discuss the ways in which specific emotions can impede or facilitate this motivational drive. From this, we discuss ways in which training in mindfulness and emotion regulation can increase the drive to be compassionate.

Here Are Some Examples of When to Use Self-Compassion

- When you’re trying hard but what you’re producing isn’t as good as you’d like it to be. Try giving yourself compassion for the feelings of frustration and disappointment.

- When you’re comparing yourself unfavorably to someone else/other people.

- When you’ve made a mistake and you’re feeling guilt or shame.

- When you’re perceiving yourself to have a big weakness, flaw, inadequacy, or as unlovable.

- When you’re having a recurring problem and feel lost, confused, or overwhelmed about how to solve it. Try giving yourself compassion, understanding, and kindness for the lost, confused, overwhelmed feelings.

- When you find yourself trying to use self-criticism to motivate yourself to change your behavior even though you’ve read the research showing it’s ineffective and usually has the opposite effect.

- When you’re feeling angry, jealous, envious, entitled, or selfish and you’re criticizing yourself for having those feelings.

- When you’re thinking “should” thoughts e.g., “I should be over this problem already” or “I should have made more progress” Tip: You can try changing “should” to “could” or “prefer” e.g., I would prefer to have made more progress.

How to Reduce Self-Criticism and Be More Self-Compassionate

Individuals can develop self-compassion. Resarchersfound that adults who wrote a compassionate letter to themselves once a day for a week about the distressing events they were experiencing showed significant reductions in depression up to 3 months and significant increases in happiness up to 6 months compared with a control group who wrote about early memories.

Researchersfound that 3 weeks of self-compassion meditation training improved body dissatisfaction, body shame, and body appreciation among women with body image concerns.

A Mindful self-compassion (MSC), program, developed by Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer,is an 8-week group intervention designed to teach people how to be more self-compassionate through meditation and informal practices in daily life. Results of a randomized controlled trial found that, compared with a wait-list control group, participants using MSC reported significantly greater increases in self-compassion, compassion for others, mindfulness, and life satisfaction, and greater decreases in depression, anxiety, stress, and emotional avoidance, with large effect sizes indicated. These results were maintained up to 1 year.

Compassion-focused therapy (CFT) is designed to enhance self-compassion in clinical populations. The approach uses a number of imagery and experiential exercises to enhance patients’ abilities to extend feelings of reassurance, safeness, and understanding toward themselves. CFT has shown promise in treating a diverse group of clinical disorders such as depression and shame,social anxiety and shame,eating disorders,psychosis,and patients with acquired brain injury.A group-based CFT intervention with a heterogeneous group of community mental health patients led to significant reductions in depression, anxiety, stress, and self-criticism. Kristin Neff also suggests that self-compassion is a teachable skill that is “dose dependent.” The more you practice it the better you get. She suggested trying:

- Identifying what you really want by thinking about the ways that you use self-criticism as a motivator (I’m too overweight, I’m too lazy, I’m too impulsive) because you think being hard on yourself will help you change. What language would a wise and nurturing mentor or friend use to gently point out how your behavior is unproductive, whilst encouraging you to do something different? What’s the most supportive message you can think of that’s in line with your underlying wish to be healthy and happy when it comes to creating these changes? Then write this down and put it somewhere you can see it each day.

- Keeping a self-compassion journal for a week (or longer if you like) and write down anything you’ve felt bad about, anything you judged yourself for, or any difficult experience that have caused you pain. For each event, practice using your kindness, sense of connectedness to humanity and mindfulness to process the event in a more self-compassionate way.

- Creating a self-compassion mantra. I found my self-critical voice was quick to remind me that “I wasn’t really good enough”, so I started gently countering this with my self-compassionate voice who reminded me that “Actually in most situations you’re better than you think you are.” This kind reminder was enough to slow down the negative spiral of fear and self-doubt, so I could mindfully attend to what was actually unfolding and make more informed choices about what I wanted to be doing. Try to create your own self-compassion mantra by thinking about what a wise mentor or kind friend would say in these moments, and try to focus on these in moments of self-doubt.

- Practice Mindfulness Meditation, a practice that allows us to sit with our thoughts and feelings without judgment. As Dr. Neff put it, “Mindfulness in the context of self-compassion involves being aware of one’s painful experiences in a balanced way that neither ignores nor ruminates on disliked aspects of oneself or one’s life.” Many forms of mindfulness meditation practices have been shown to reduce psychological distress and help stop rumination. In addition, practicing yoga with meditation has been shown to lead to less self-criticism. Most of us get into trouble when we start blindly believing or focusing in on our flaws. We lose ourselves to self-evaluation, self-criticism, and even self-hatred. This leads to self-limiting or self-destructive behavior. Mindful meditation helps us to get a grasp on these thoughts before they take over.

You’ll find many more resources on self-compassion including extra exercises and meditations. You can try at Neff’s website www.self-compassion.org. There is also some promising emerging research around the eight-week Mindful Self-Compassion courses you can find in many countries that incorporates formal meditation practices, interpersonal exercises and home practices.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.

.

.