By Ray Williams

December, 2021

Cruel jokes about the elderly are everywhere. We need to face our ageism tsunami and change our attitudes and policies about growing older.

If you watch Saturday Night Liveor other TV comedy shows, there’s been an increasing number and frequency of jokes about elderly people, depicting their declining cognitive functions, the “repulsiveness” of an elderly body (particularly female), or physical infirmities. If the same kind of cruel mocking took place with an ethnic or racial group, women or the LGBT community, network heads would roll. But it’s tolerated for the elderly.

The consequences of ageism influence how we are able to live the last third of our lives, and can even affect our life span.

The World’s Population is Aging

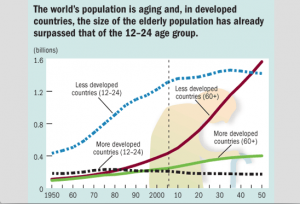

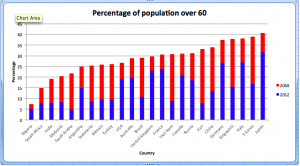

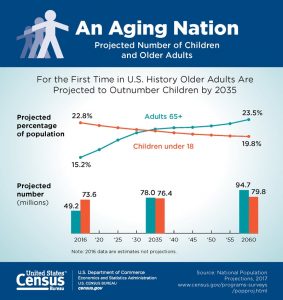

The world’s population is aging. By 2050, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates two billion people will be aged 60 years or older, up from 900 million in 2015. By 2030, Asia will be home to 60 per cent of the world’s over 65. A study by the Urban Institute, The Aging Baby Boom: Implications for Employment and Training Programs, concludes that by 2050, the median age of population in the following countries will be: Japan-52, Italy-52, U.K.-43, Finland-46, the U.S. and Canada-42. In the European Union in the next 10 years, the number of workers 50-65 will increase 25% while the percent aged 20-30 will decrease by 20%. Over 1 million people ages 90 to 100 will be working in Japan by 2030.

Currently, about 28% of the U.S. population is 50 or older. Projections show that by 2025, that figure will increase to more than 35%; the number of 35-44- year-olds who are normally expected to move into senior management ranks will actually decline by 10%; and the number of U.S. workers between the ages of 45 and 54 will grow by 21%, while the number of 55 to 64-year-olds will expand by 52%.

By 2021, for the first time in history, the number of older people will outnumber the number of children younger than 5 years of age. The average life expectancy is expected to rise to 110 by 2030 in Japan and Germany–officially termed “super aged.” Four more countries—Greece, Finland, Spain and Canada–are expected to enter the super aged category. According to the Global Age Watch Index, Norway has been nominated to be the most likely country to grow old out of 96 countries.

What is Ageism?

The term “ageism” was coined in 1969 by Robert N. Butler, M.D., then a 42-year-old psychiatrist who (among his other civic and age-focused advocacy responsibilities) headed the District of Columbia Advisory Committee on Aging. In partnership with the National Capital Housing Authority (NCHA), Butler used the term “age-ism” during a Washington Postinterview conducted by then cub reporter Carl Bernstein.

It has also been called by others names such as The Silver Tsunami (also known as Grey Tsunami, Gray Tsunami, Silver Wave, Gray Wave, or Grey Wave), a metaphor used to describe population aging. The silver tsunami metaphor has been used in popular media and in scholarly literature to refer to the late-twentieth century demographic phenomenon of population aging in major media platforms– including The Economist, Forbes, and multiple news outlets.

The phrase has also been used to refer more specifically to health and economic implications associated with population aging by major medical publications including The British Medical Journal, New England Journal of Medicine, and professional organizations including American Psychological Association. Scholars from a range of disciplines including humanities, health professions, and social science have argued that the silver tsunami does not constitute neutral language to describe population aging, calling it “dangerous” and “a nasty metaphor for older adults”.

Critics of the silver tsunami phrase (and its variants) have argued that it represents an important example of ageist language. For example, Andrea Charise writes that the prevalent use of this metaphor in popular and professional media “testifies to the barely conscious figurative language that serves to construct perceptions of an aging population.”

The Winter 2010 President’s Message from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research begins by invoking “the ‘grey tsunami’—the tide of chronic diseases rising from an ageing population which threatens to swamp our health-care system, economy, and quality of life.” Similarly, in 2010 the Alzheimer Society of Canada published a major commissioned report on the projected impact of dementia entitled “Rising Tide.” This ominous rhetoric of rising, swamping, tides, and disease—amplified by the authoritative tones of medical and health policy expertise—conceives of population aging as an imminent catastrophe”

In a 2013 editorial in the Journal of Gerontological Social Work entitled “The Aging Tsunami: Time for a New Metaphor?”, Amanda Barusch builds on this objection, by describing the “inaccurate, damaging perceptions” of older age. “The specter of millions of dependent elders sweeping over the land makes us shiver.”

In a content analysis (2009) of The Economist’s digital archive between 1997 and 2008, Ruth Martin, Caroline Williams, and Desmond O’Neill conclude that “There is a noticeable trend to ageism in one of the most influential economic and political magazines in the world. “In place of the silver tsunami’s “apocalyptic” imagery, critics have suggested abandoning the metaphor in favor of different, and ideally more neutral, terminology with less overtly ageist connotations. “Geriatricians and gerontologists who want to influence policy makers to improve services for older people will need to engage in a dialogue with journalists in areas other than the biomedical literature.”

Ageism, also spelled agism, is stereotyping and discrimination against individuals or groups on the basis of their age. This may be casual or systematic. The term was coined in 1969 by Robert Neil Butler to describe discrimination against seniors, and patterned on sexism and racism. Butler defined “ageism” as a combination of connected elements. Among them were prejudicial attitudes towards older people, old age, and the aging process; discriminatory practices against older people; and institutional practices and policies that perpetuate stereotypes about elderly people.

In his book Why Survive? Growing Old in America, Butler says “Ageism can be seen as a systematic stereotyping of and discrimination against people because they are old, just as racism and sexism accomplish this with skin color and gender . . . I see ageism manifested in a wide range of phenomena, on both individual and institutional levels—stereotypes and myths, outright disdain and dislike, simple subtle avoidance of contact, and discriminatory practices in housing, employment, and services of all kinds.”

Based on a conceptual analysis of ageism, a new definition of ageism was introduced by Iversen, Larsen, & Solem in 2009: “Ageism is defined as negative or positive stereotypes, prejudice and/or discrimination against (or to the advantage of) elderly people on the basis of their chronological age or on the basis of a perception of them as being ‘old’ or ‘elderly’. Ageism can be implicit or explicit.

Researchers have also found that ageism is surprisingly commonplace. In one study published in a 2013 issue of The Gerontologist, researchers looked at how older people were represented in Facebook groups. They found 84 groups devoted to the topic of older adults, but most of these groups had been created by people in their 20s. Nearly 75 percent of the groups existed to criticize older people and nearly 40 percent advocated banning them from activities such as driving and shopping.

In a survey of 84 people ages 60 and older, nearly 80 percent of respondents reported experiencing ageism–such as other people assuming they had memory or physical impairments due to their age. The 2001 survey by Duke University’s Erdman Palmore, PhD, also revealed that the most frequent type of ageism–reported by 58 percent of respondents–was being told a joke that pokes fun at older people. In an issue of The Gerontologist thirty-one percent reported being ignored or not taken seriously because of their age.

Margaret Morganroth Gullette’s 2017 book, Ending Ageism or How Not to Shoot Old People, provides multiple examples to illustrate the pervasiveness of ageism and delivers a call to action.

Changing Views of Aging Over Time

The Old Testament describes King David’s death: “. . . and he died at a good old age, full of dogs, riches and honor”. Among ancient Hebrews, “The wisdom of our fathers,” which was written sometime after the birth of Christ states that if one reaches the age of 80, it is a story of survival. In contrast, if one reaches the age of 90, one is frail and “bending over the grave”.

Among Greek philosophers, Plato sees successful aging through spirituality. He wrote: “The spiritual eyesight improves as the physical eyesight declines”. The Romans honor and even idealize old age. Cicero claimed: “Old age, especially an honored old age, has so great authority that this is of more value than all the pleasures of youth.”

In Shakespeare’s play, As You Like It, he portrays a very negative picture of aging: “last scene of all, that ends this strange eventful history, is second childishness and mere oblivion, sans teeth, sans eyes, sans everything” This dim medieval view speaks to the lack of prospects for successful aging.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe saw aging thus: “youth is drunkenness without wine; if old age can drink itself back to youth, that is a wonderful virtue.” Yet he also says, “So lively brisk old fellow doesn’t let age get you down. White hairs or not you can still be a lover.”

In the 20th century, historian Will Durant observed, “The individual succumbs but he does not die if he has left something to mankind.” To acknowledge an appreciation of the very subjective aspects of successful aging, we only need to consider Bernard Baruch’s view: “To me old age is always 15 years older than I am.”

It would be accurate to say that for the most part in Western society, aging is viewed in a negative way, where somehow older people are viewed as less than able and capable, and to some degree helpless. Which can account for how older people can be made the object of ridicule or humor, or at a minimum, a nuisance to be tolerated but kept out of sight.

Ageism Stereotypes

Pulitzer Prize winning author Robert Butler spoke at a Symposium on Geriatric Medicine in 1974: “Those who think of old people as boobies, crones, witches, old fogies, pains-in-the-neck, out-to-pasture, boring, garrulous, unproductive, and worthless, have accepted the stereotypes of aging, including the extreme mistake of believing that substantial numbers of old people are in or belong in institutions.” In the same talk, he condemned health professionals and academics for perpetuating these stereotypes: “Medicine and the behavioral sciences have mirrored social attitudes by presenting old age as a grim litany of physical and emotional ills.

Researcher Susan Fiske has suggested that stereotypes about older people often relate to how younger people expect them to behave. She argues:

- The first stereotype she described relates to succession. Younger people often assume that older individuals have “had their turn,” and should make way for the younger generations.

- The second stereotype relates to what Fiske refers to as consumption. Younger people frequently feel that limited resources should be spent on themselves rather than on older adults.

- Finally, young people also hold stereotypes about the identity of older adults. Younger people feel that those who are older than they should “act their age” and not try to “steal” the identities of younger people, including things such as speech patterns and manner of dress.

Not only are negative stereotypes hurtful to older people, but they may even shorten their lives, finds psychologist Becca Levy, PhD, assistant professor of public health at Yale University. In Levy’s longitudinal study of 660 people 50 years and older, those with more positive self-perceptions of aging lived 7.5 years longer than those with negative self-perceptions of aging. The study appeared in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Intergenerational tensions flamed ageist rhetoric in the 1980s and 1990s, as reflected in The New Republic which depicted older people as “greedy geezers” who squandered their life savings and depleted Social Security funds.

Myths About Aging

In my article in The Financial Post, I outlined several myths and facts about the issue of aging:

- Myth 1: A significant per cent of older people are either senile or suffer from dementia. Fact: Only 6% to 8% of people over the age of 65 have dementia.

- Myth 2: Older people suffer from rigid thinking. Fact: 41% of people over 65 use the Internet. Brain science shows we can learn easily well into our nineties.

- Myth 3: Most older people have health problems. Fact: 75% of people aged 65-74 are in good health; over 60% age 75+ are in good health; 40% over age 80 are fully functional.

- Myth 4: Older people exhibit significant cognitive decline. Fact: A recent study showed that in terms of verbal meaning, inductive reasoning, spatial orientation, numerical ability and word fluency the people studied who were 50 to 80 did not show any significant decline.

Positive Perspectives on Aging

People’s positive beliefs about and attitudes toward the elderly appear to boost their mental health. Levy has found that older adults exposed to positive stereotypes have significantly better memory and balance, whereas negative self-perceptions contributed to worse memory and feelings of worthlessness. “Age stereotypes are often internalized at a young age–long before they are even relevant to people,” notes Levy, adding that even by the age of four, children are familiar with age stereotypes, which are reinforced over their lifetimes.

Some of the world’s great achievements were accomplished by older people, not the youngest geniuses: It was during their “sunset strolls,” that Michelangelo, at 88,was designing the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica; Stradivarius, in his 90’s produced two of his most famous violins; Verdi, when 80, composed the opera “Falstaff;” Mary Baker Eddy founded the Christian Science Monitor at 87; Frank Lloyd Wright was 91 when he designed the Guggenheim Museum; Peter Drucker wrote his famous book on management when he was 89; George Burns was still performing in his 90’s; Dr. Seuss was 82 when he wrote one of his last children’s books; Olive Riley, who was believed to be the world’s oldest blogger at 108, wrote a blog every day; Arthur Winston, 100, worked for 72 years for the same company, Los Angles Metro; Jennifer Figge, 57 was the first woman to swim the Atlantic Ocean; John Whittemore, 104, continued to compete in Track and Field; and John Kelly was still competing in Marathon and Iron man competitions at 97.

Fueling the problem is the media’s portrayal of older adults, Levy says. At an U.S. Senate hearing, Levy testified before the Special Committee on Aging about the effects of age stereotypes. Doris Roberts, the Emmy-award winning actress in her seventies from the T.V. show “Everybody Loves Raymond,” also testified at the hearing.

“My peers and I are portrayed as dependent, helpless, unproductive and demanding rather than deserving,” Roberts testified. “In reality, the majority of seniors are self-sufficient, middle-class consumers with more assets than the youngest people, and the time and talent to offer society.” Indeed, the value that the media and society place on youth might explain the growing number of cosmetic surgeries among older adults, Levy notes.

Many of these prerequisites originated in the pervasive notion that older people, uniformly, were poor. That is no longer the case. As a group, the old, on average, have more income at their disposal than younger cohorts. We also commonly think of older people as being poor and penniless. But the current senior population possesses over $900 billion in spending money in the U.S. Nearly a quarter of householders aged 65 to 69 have a net worth of $250,000 or more. Seniors spend more than $30 billion on travel each year. According to George Moschis of the Center for Mature Consumer Studies, “the 55-plus age group controls more than three-fourths of this country’s wealth and the 65-plus group has twice as much per capita income as the average baby boomer.”

Aging Narratives

The “Vibrant Senior” narrative

The “Vibrant Senior” narrative centers on a particular definition of successful aging: the maintenance of physical activity. This narrative focuses on how older Americans must decide to remain active. Motivation, willpower, and individual action figure prominently in this narrative, as do “epiphany moments”—older adults’ realizations that their fates are in their hands, and they must decide to change their lives and become active if they are to enjoy their older years. This narrative emphasizes the role of not only physical health and vitality, but also of mental and cognitive dimensions of health. It identifies a central role for family members in helping or impeding older adults’ ability to achieve the “Vibrant Senior” ideal. Finally, this narrative tends to link older adults’ physical well-being and activity to broader societal goals—often explaining how active older Americans contribute to national prosperity and collective economic well-being.

The “Independent Senior” narrative

The “Independent Senior” narrative focuses on autonomy as another dimension of successful aging. It elevates self-sufficiency as the marker of successful aging, and features discussions of transportation, social relationships, political engagement, financial independence, and the ability to make autonomous decisions about end-of-life care. Critically, it represents the need to ensure older adults can remain independent as a moral obligation, as well as a way to respect the wisdom of our aging population. In telling this story, advocacy organizations often focus on the social and economic conditions that make independent living more or less likely to occur. They frame older adults’ independence as a public issue, focusing on the financial requirements of independent living, framing independence not simply as a matter of choice, but as the result of a host of factors, including access to supports and resources.

The “Throwaway Generation” narrative.

The “Throwaway Generation” narrative focuses on negative treatment of older adults, particularly elder abuse and discrimination. This was the most frequent narrative used in advocacy materials. The narrative holds private industry—such as nursing homes, assisted living facilities, or private employers—accountable for the maltreatment of older adults. Proposed solutions typically involve changes to these institutions, such as greater oversight of employees who work with older Americans, and increased legal protections for workplace discrimination. The narrative asserts that the issue of elder abuse requires policy-level action. The narrative also frequently casts the maltreatment of older Americans as a violation of human and civil rights.

Capabilities: “Aging = Decline” Narrative

The prevailing thinking by the majority of the public sampled was an association between aging and decline. The most common language about aging was of “loss,” “slowing down,” and “breaking down.” There was a strong belief that a loss of control and deterioration are inevitable as one ages. Consistent with that belief was an emphasis on the increased need for healthcare and the difficulty of meeting healthcare needs. The public also believes older adults can no longer learn new information—they stagnate, and they are digitally incompetent. The public characterizes the aging process as one in which identity, knowledge, skills, success, and other aspects of life become increasingly “fixed.”

Elders’ role in society: “Older Adults Seen as the ‘Other’” Narrative

The second grouping of perceptions—the role of older adults in the broader society—revealed that “the elderly” are seen as “other.” Older adults were compartmentalized from the rest of society and the language of “battling” or “working against” aging dominated. Rather than recognizing that aging is relevant to all of us, those interviewed perceived older adults as an external group that competes with the rest of society for resources. The belief that older adults are “other” contributes to a zero-sum thinking wherein policy discussions about aging are characterized as more resources for “them” means less for “us.” Such thinking makes it difficult to see aging as a public issue. Also, the belief that the past—when generations of families lived close to each other and there was a booming economy— was better than today reinforces fatalism and the belief that “nothing can be done.” This dissuades people from thinking about public policy and community-based solutions.

Culpability: “It’s Their Fault” Narrative

The final set of misconceptions is about culpability. The responses from the public about older individuals were consistent with a basic American cultural belief that holds each person accountable for his or her circumstances. The public believes the well-being of older adults is exclusively the result of individual lifestyle choices and financial planning. By extension, it implies that those who ate well and exercised throughout their lives are the healthy older adults and those suffering disabilities must not have adequately taken care of themselves. Similarly, the public believes people need to take control of their financial security throughout their lives. Therefore if, as an older person, you are economically strained, it must have been a result of your own doing. Finally, the public asserted a belief in “mind over matter.” That you are as old as you feel and that people’s experience of aging is determined by their attitude, willpower, and choices. The implications of the public’s focus on individual responsibility is that it minimizes the consideration of systemic influences on well-being and deflects the consideration of policies as an important driver of older adults’ full participation in society. It denies our collective responsibility, it ignores any concept of a social contract, and it creates an obstacle to the aging community’s efforts to improve the quality of life of older adults.The “Demographic Crisis” Narrative

The “Demographic Crisis” narrative describes the “graying of the American population” as an impending social crisis with wide-reaching consequences. This narrative employs statistics related to demographic change in order to convey a sense of urgency about aging issues—the assumption being, presumably, that urgency will motivate readers to act. This narrative also points to steps individuals should take to weather the upcoming demographic “storm.” For example, it urges policy makers to address housing issues that will result from an aging population. It is important to note, however, that this narrative holds older Americans and their families responsible for addressing their own housing needs.The “Government as Problem” Narrative

Advocacy organizations regularly point to governmental action as a causal factor in older Americans’ financial challenges. In particular, these stories decry the impact of federal budget cuts on older Americans’ financial stability.

Research on Ageism

Extensive research on ageism has only become a trend in recent years. Here are some of the findings:

- According to Erdman Palmore’s research, Individuals of advanced age are both under-treated and over-treated by our healthcare system.

- Age limits our ability to be hired and re-hired after market downturns according to a 2015 U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics report, putting further economic pressure on the lives of older adults.

- Perceptions about older adults constrain the types of roles they assume in the community, limiting them as individuals and preventing communities from gaining the wealth of knowledge, wisdom, and energy from what some call our fastest growing natural resource according to (Greenya and Golin, 2008).

- At the extreme, ageism is believed to shorten our lives. One study reported that older adults who held negative views about old age faced life expectancies that were, on average, seven and a half years shorter than those of their peers Becca Levy reports in her research.

- In one study, 70 percent of older adults surveyed reported that they had been insulted or mistreated on the basis of their age. In a survey of eighty-four people, ages 60 and older, nearly 80 percent of respondents reported experiencing ageism.

- Camilla Cavendish, author of the book Extra Time: 10 Lessons for an Ageing World, reports that the U.K. Office for National Statistics estimates that one in three babies born in Britain today will live to 100. Some scientists even think we could live to 150.

- More than 80% of global GDP is generated by countries with rapidly ageing populations. How these seniors directly and indirectly shape their economies – especially in a political sense – will henceforth be an important factor when trying to understand global and domestic political economy trends.

- Aging Baby Boomers today account for 80 per cent of the net worth in the U.S. They are the most numerous and the most successful entrepreneurs, according to research conducted by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation.

- By associating late life with disease and death, generations down the ages have justified the futility of granting the aged access to care.

- Ageism is ubiquitous—evident in places as far-flung and with differing cultures as Japan and east Africa—and embedded in Western culture.

- In the fall of 2012 of the leaders of eight national aging organizations: the American Society on Aging, AARP, the American Federation for Aging Research, the American Geriatrics Society, Grantmakers in Aging, the Gerontological Society of America, the National Council on Aging, and the National Hispanic Council on Aging gathered to review the the topic. Their research, captured in the report, Gauging Aging: Mapping the Gaps Between Expert and Public Understandings of Aging in America, by the FrameWorks Institute, provided much needed data on ageism including public attitudes and needed policy changes.

- According to Eric Lindland and associates, in their book, Gauging Aging: Mapping the Gaps Between Expert and Public Understandings of Aging in America,Older Americans benefit from age-based discounts and entitlements, which is a positive development, but the benefits still convey a scent of ageism. With the right contextual and social supports, older adults remain healthy and maintain high lives of independence and functioning.

- Even “positive” views of older adults often depict them as warm but incompetent, leading others to pity them.

- According to the New York Times, the phrase “OK Boomer” is “Generations Z’s … retort to the problem of older people who just don’t get it.” OK Boomer now appears on phone cases, stickers, pins, and sweatshirts and on a range of products that say, “OK boomer, have a terrible day.” And yet one wonders if the public would be quite so amused by a logo that said: “OK Jews, have a terrible day.” The accepted explanation and justification for all this, says the article, is that the old have ruined things for the young: The story goes that the aging are responsible for climate change, for income inequality, for the cascading series of financial crises, for the prohibitive cost of higher education. Is it unjust to direct one’s anger at the average middle-class senior citizen struggling to survive on social security rather than raging at, let’s say, the Koch brothers the Sacklers, the big banks, and the fossil-fuel lobbyists who have effectively dismantled the EPA.

- Research also has shown that awareness of negative stereotypes undermines cognitive performance, and that holding negative beliefs about aging is associated with relatively shorter life expectancies and poorer health over time.

- Ageism has been termed the third “-ism,” similar in many ways to racism and sexism. Research suggests that the strength of effect sizes for biases against the old are comparable—or even larger—than those observed in other forms of discrimination.

Ageism became the cornerstone of Erdman Palmore’s research while he was a graduate student in the 1950s. With Kenneth Manton, Palmore published the first systematic comparison of age-based inequality to racism and sexism: “Few people recognize the magnitude of age inequality in our society.”

In 1976, Palmore developed, and subsequently maintained, a twenty-five-point “Facts on Aging” quiz to help the public recognize the extent of their misinformation about older people’s qualities—a bias that contributed to age discrimination. In a guest editorial, Palmore (2000) offered usage guidelines for avoiding ageism in gerontological language. At age 82, he co-edited the Encyclopedia of Ageism, wherein sixty authors reviewed 125 aspects of ageism, ranging from mapping elder abuse to assessing ageism among children.

Experts talked about the large demographic shift toward an aging society, with both the number and longevity of older adults increasing. They clarified that the increase in longevity has not resulted in an increase in the number of years of disability or poor health, but in an increase in the number of productive years of life. Experts also resisted generalizations about older adults, emphasizing instead the heterogeneity of the group across a more than forty-year age span, and variations in health, financial situation, and functional status.

The consequences of these deeply held perceptions, which are at odds with the research evidence shared by experts in aging, is a sense of fatalism and anxiety associated with aging. The logical conclusion from the common theme of the misperceptions is that there is nothing that can be done, successful aging is directly tied to an individual’s choices, and any improvements for the future will come from sharing and applying already available information.

The biggest problem among the dominant patterns of public understanding identified in our research is the common assumption that individuals are exclusively responsible for how they age. This idealized vision of aging is rarely achievable in the real world, according to experts. When advocacy organizations fail to link successful aging to policies that enable older Americans to remain active and socially engaged, they reinforce the public’s highly individualistic understandings of the aging process. The result is that people understand successful aging as the exclusive result of lifestyle choices, rather than recognizing the contribution of social supports, structures, and policies. Further, when the ideal is not achieved, Americans tend to assume that the reason for the failure lies in poor individual decision-making and lack of discipline and willpower.

Aging and Ageism Globally

The Blue Zones

On the Pacific island of Okinawa, there is no word for retirement. The longest-living women in the world are still caring for great-grandchildren when they hit their 100s. Okinawans are rarely lonely, because they are supported by a network of friends, the ‘moai’, who are committed to share both good times and bad. The typical Okinawan house doesn’t have much furniture: people tend to eat sitting on the floor, so they are getting up and down many times a day. They also have a strong sense of ‘ikigai’, roughly translated as ‘reason for being’. My Japanese friends tell me that you find your ikigai at the place where your values intersect with what you enjoy doing, and what you are good at.

Okinawa is one of the Blue Zones, the parts of the world identified by researcher Dan Buettner, where people have low rates of chronic disease and live exceptionally long lives. While it’s not possible to distil a single magic ingredient, common to all Blue Zones are plant based diets with very little processed food, strong friendships and a sense of purpose, lots of sleep and strenuous physical activity.

Japan and China

North-east Asia is already ahead of that curve. Japan has the oldest population among the world’s high-income countries, while China – a developing country – is home to the world’s largest number of elderly citizens and its population is ageing increasingly rapidly. The former governor of the Bank of Japan, Masaaki Shirakawa, wrote recentlyabout the fact that Japanese officials had long misdiagnosed the country’s persistent deflation as having primarily economic rather than demographic drivers. Since the delay in identifying that driver had aggravated the ensuing policy challenges, he urged other countries to learn from Japan’s mistake.

Following its one-child policy, which was ended in 2015 after more than 30 years, China’s fertility rate rapidly converged with the below-replacement-level fertility rates of the high-income north-east Asian economies – Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore – even though China remains a developing country. Alongside rapid gains in life expectancy, the world’s largest population and a relatively early retirement age (55 for women and 60 for men), China is also home to the largest number of retirees; some 241 million Chinese were aged 60 and over in 2017.

China’s related policy discourse is as unique as its demographic profile. To that end, and in contrast to Japan, Chinese policymakers who fear for their country’s national development prospects have been studying – and adjusting for – the effects of demographic change on China’s economy for more than three decades. That research, thanks to the work led by demographer Cangping Wu, set out that China had no hope of getting ‘rich’ before it would get old.Fearing that first getting ‘old’ would itself derail national modernization, China’s policymakers have since tried to ensure that ‘premature ageing’ will not derail the country’s prospects of economic maturity.

In other words, China’s policymakers did not just have an economic strategy, but an economic demography strategy. That is, China had realized early on that economic and demographic change are co-integrated – something all countries, rich and poor, young and old, might learn from.

While China may still be old and not rich (at least not yet), it has nonetheless been quick to adopt a strategic approach to economic policymaking that directly reflects the co-integrated nature of economics with demography over time. As such, China is the founder of the economic demography transition approach to policymaking and national development. All countries would do well to heed its approach when considering their own national economic and demographic circumstances.

The Influence of the Media’s Portrayals of Elders

Myths about aging are perpetuated by our media. The movie, Cocoon, a movie about older people, starred Don Ameche, Hume Cronyn, Jessica Tandy, who were all over the age of 70 at the time tried to deal with the issue of aging. When the film’s director, Ron Howard, reviewed the film’s early takes, he decided something was wrong. His actors weren’t acting like old people—their posture was too straight, step to lively, and speech too clear. So Howard hired acting instructors to teach them how to act like much older, less able people.

Advocates and experts working on behalf of older Americans have long suspected that media representations of aging are inaccurate. Scholarly research confirms this assertion. Compared to other age groups, older adults—particularly older women—are grossly under-represented in the media. When the media do feature older adults, they present one of two extreme characterizations: frail, diseased, senile, and dependent—or active, healthy, and wholly independent. These negative representations feed problematic public perceptions of the aging process and stereotypes about older Americans. Ironically, the media’s positive images of aging are just as unproductive, as they link successful aging to individual lifestyle and consumption choices (e.g., choosing to eat well, having the drive to exercise regularly, and being disciplined in financial matters). By equating successful aging with individual choice, and ignoring the social supports necessary to enact these decisions or the structural factors that constrain them, media depictions imply that most older Americans simply fail to choose to “age well.” These media patterns shape and constrain public opinion about aging.

Ageism in Hollywood, specifically in terms of women, is profound, from the way youth is praised to the lack of jobs for older actresses. The way youth is praised reflects directly on the way older women are presented in the media. President and CEO of the American Association of Advertising Agencies, O. Burtch Drake, has said, “older women are not being portrayed at all; there is no imagery to worry about.”Women over fifty are not the center of attention and if an actress is older they are expected to act anything but their age. These same women who have been acting since their teenage years, who have always been told to act their age, now must change the dynamic of their job by not acting their age when they get to be considered old by society and the media.

The standards set in the film are fixated upon youth – sexuality, beauty, physicality. Movies that portray women acting their own age (i.e. a 50-year-old acting 50 years old) seems exaggerated and unrealistic because it does not fit the norms associated with women in film and media.Women are forced to feel that they must continuously improve upon their looks to be seen and they can be replaced by a younger model of themselves. “Silver ceiling” references the new type of ceiling older workers in the entertainment industry, especially women, are being faced with. Underemployment of older actresses surpasses that of older actors because of the typical pairing of older actors with younger actresses in films.

A BBC news survey found that “on television older men significantly outnumber older women by about 70 percent to 30 percent.” An issue amongst older women is that their voices are not being heard, which is especially true for older actresses in Hollywood. The issues about employment they are bringing to light as well as the complaints they have received have not being taken seriously.

Because of the limited ages the film industry portrays and the lack of older actresses, society as a whole has a type of illiteracy about sexuality and those of old age. There is an almost inherent bias about what older women are capable of, what they do, and how they feel. Amongst all ages of actresses there is the attempt to look youthful and fitting to the beauty standards by altering themselves physically, many times under the hands of plastic surgeons.Women become frightful of what they will be seen as if they have wrinkles, cellulite, or any other signifier of aging.As women reach their forties and fifties, the pressure to adhere to societal beauty norms seen amongst films and media intensifies in terms of new cosmetic procedures and products that will maintain a “forever youthful” look.In terms of sexuality, older women are seen as unattractive, bitter, unhappy, unsuccessful in films.

The idea that younger actresses are better than older actresses in Hollywood can be seen by the preferences of the people who are watching movies. Movie spectators display discrimination against older women in Hollywood. A study between 1926-1999 proved that older men in Hollywood had more leading roles than women who were the same age as them.There are many cases where leading actors play the attractive love interest for longer than women.This portrayal of women never aging but men aging can harm not only actresses in Hollywood but also women who are not in the media. There are fewer older actresses who get leading roles than young actresses. This promotes the idea that women do not age and that older women are less attractive. This can be harmful to women because they will strive for something that is impossible to have, eternal youth.

In film the female body is depicted in different states of dress and portrayed differently depending on the age of the actress. Their clothing is used as an identity marker of the character. Young women are put into revealing and sexy costumes whereas older women often play the part of a mother or grandmother clad in appropriate attire. This can include a bonnet or apron as she carries about her matronly duties.This can lead both men and women to perceive the female body in a certain way based on what is seen on screen. Ageism is not new to Hollywood and has been around since the time of silent films. When transitioning from silent movies to talking motion pictures, Charlie Chaplin (a well known silent movie actor) said in an interview that “It’s a beauty that matters in pictures-nothing else…. Pictures! Lovely looking girls…What if the girls can’t act?…”

In a 2005 interview, actor Pierce Brosnan cited ageism as one of the contributing factors as to why he was not asked to continue his role as James Bond in the Bond film Casino Royale, released in 2006. Also, successful singer and actress Madonna spoke out in her 50s about ageism and her fight to defy the norms of society. In 2015, BBC Radio 1 was accused of ageism after the station didn’t add her new single to their playlist. Similarly, Sex and the Citystar Kim Cattrall has also raised the issue of ageism.

Ageism in the Workplace

Nearly 2 out of 3 workers ages 45 and older have seen or experienced age discrimination on the job, according to the results of a wide-ranging AARP workplace survey released Thursday. Among the 61 percent of respondents who reported age bias, 91 percent said they believe that such discrimination is common. To learn more about what older workers think about workplace issues ranging from age discrimination to income to interactions with coworkers, AARP surveyed 3,900 people over age 45 who either were employed or looking for work. The overall results of the Value of Experiencesurvey show that while most older Americans continue to work for financial reasons, they also want to be in roles in which they gain personal fulfillment and respect. Some survey participants believe that the prevalence of age bias could affect both of those career goals.

For example, according to the survey, 16 percent of respondents believe they did not get a job they applied for, 12 percent said they had been passed over for a promotion, and 7 percent said they had been laid off, fired or forced out of a job — all because of age discrimination. And 76 percent of all respondents said age bias could mean it would take them longer than three months to find a new position.

“The reality is that older workers are appreciated by many employers for their commitment to being on the job,” says Kathleen Christensen, director of the Sloan Foundation’s Working Longer program.

Beyond concerns about age discrimination, the overall survey results make it clear that income is the key factor influencing older adults’ employment decisions. Indeed, when asked to rate which factors most influenced their choice to work or look for a job, the most popular response (87 percent) was “need the money,” and 84 percent said they wanted “to save more for retirement.”

Longer lives will demand longer working lives for most North Americans, as the vast majority cannot save enough during forty years of work to support thirty (or more) years in retirement. Even beyond the financial need to work, workforce participation holds benefits for physical and psychological well-being, along with anchoring individuals within the broader society. Since 2000, a decades-long trend toward ever-earlier retirements reversed and there has been a steady increase in retirement age over the last decade. Baby boomers say they plan to work past traditional retirement age and empirical evidence suggests that such statements are good indicators of future workforce participation.

It has yet to be seen, however, whether employers are interested in recruiting and retaining older workers. Labor economists regularly voice concerns about slowing productivity associated with an older workforce. The belief that older workers take jobs from younger workers remains widespread, despite compelling evidence that older people’s workforce participation is associated with less (not more) unemployment among younger workers. Although the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA) was passed in 1967 in the U.S., this legislation has been relatively ineffective. Wrongful termination is the most common complaint under the ADEA, and many suspect that the legislation reduced employers’ inclinations to hire older workers due to fears of potential litigation.

One area where research is sorely needed concerns age differences in productivity. As noted, claims that older workers are less productive than younger workers are made on a regular basis, using cognitive slowing and physical decline as justification. There is very little evidence, however, that age-related changes in laboratory-documented cognitive performance are associated with reductions in work performance. On the contrary, performance in knowledge-based jobs appears to benefit from experience, thereby advantaging older workers. In exceptional cases where there are observed reductions in performance, it is important not to assume simply that age-related decline is the cause.

Employers also are affected by time horizons, often not investing in employee training by mid-career and creating vicious cycles where perceptions about outdated skills are reified by workplace practices; for example, emphasizing the acquisition of new skills and efficiency in reviews of younger workers, while ignoring skills that develop over time and often contribute to greater cohesion of work groups, such as expertise and generativity.

To date, research on older workers’ strengths is nearly non-existent. Yet, there is evidence of improvement in a range of qualities that likely benefit work performance. Relative to younger adults, for example, older adults are more emotionally stable, less likely to experience anger or fear, and more likely to be interested in making meaningful contributions. In addition to having more knowledge and expertise, older people generate wiser responses to emotionally charged interpersonal problems and solutions for intergroup conflicts. Such qualities hold great potential for workplace productivity and cohesion, yet the ways in which they operate in work settings remain largely unrecognized or studied.

There is growing evidence that benefits may accrue to employers with mixed-age teams—benefits that can also extend to consumers. A report from McDonald’s documented greater customer satisfaction at locations employing a mix of older and younger workers. Automaker BMW reported that mixed-age workforces facilitate knowledge transfer. Mentorship training models also appear to benefit productivity.

Study after study has shown how employers or hiring managers may not objectively evaluate job candidates’ potential productivity and are thus biased about demographic characteristics in recruiting and performance reviews. For example, in a matched-resumé field study, Richard Lahey found that employers were over 40 percent more likely to call a female job candidate for an interview if the high school graduation date on the resumé signaled the applicant was younger rather than older. Other researchers found that assertiveness appears to be interpreted more negatively when the assertive person is older.

Current rapid technological change along with the Great Recession of 2007–2009 has meant older workers face a higher likelihood of remaining unemployed long term. In 2014, 45 percent of unemployed 55- to 64-year-olds were reported as unemployed long term (i.e., twenty-seven weeks or longer), versus 33 percent of 25- to 34-year-olds. And over the past thirty-five years, the share of unemployed people (for any length of time) who are ages 55 years or older has grown steadily from well below to on par with that of 35- to 44-year-olds and 45- to 54-year-olds.

Yet, studies of older workers in the workplace have shown that they engage in less unethical and/or criminal activity; have higher levels of participation in politics and volunteerism; have fewer workplace accidents; have better visual acuity; have less conflict with co-workers; have fewer power struggles; are less ego driven; have less health costs than younger workers; have greater loyalty to the organization; have more positive attitudes than younger workers; are more resilient under stress; do better quality work; have less job turnover; are more trainable, and have a less net cost compared to younger workers.

One of the critical issues we face in the retirement of aging workers is the loss of knowledge. A 2006 Ernst and Young report found that companies are more likely to be concerned about knowledge loss and transfer, but they are doing little about it.

There are some companies addressing this issue now. For example, Finland’s Abloy lock company, which operates in 40 countries, and has 30% of its workers over the age of 55, created the designation of Agemaster, which entitles older workers to an assortment of benefits — massages, free memberships in health clubs, free education, all funded by the company, free complete physical exams and fitness tests, and an annual five week vacation.

Older workers—or “perennials,” as this cohort has sometimes been called—are now the fastest-growing population of workers, with twice as many seniors as teenagers currently employed in the US. In the 30-year span from 1994 to 2024, workers aged 55 and older will go from being the smallest segment of the US working population to the largest, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Other industrialized nations are seeing similar trends; in Japan and South Korea, the workforce is aging even faster. The aging of the workforce is in part driven by employees who want to keep working—or at least, to keep earning—well into their 70s and even 80s.

Meanwhile, the corporate shift from defined-benefit retirement plans, which guaranteed a steady income, to defined-contribution plans, which place the onus of saving on workers, has left many older people financially unable to quit work without a substantial drop in their standard of living.

Nearly half of current retirees surveyed in 2014 said they were still doing some paid work in retirement. But even the subset of these workers who are continuing to work past retirement out of choice rather than necessity often desire some kind of transition by the time they are past retirement. That may mean part-time work, to allow for more free time with family, or less time at a job that’s become more physically taxing, or flexibility to accommodate other lifestyle changes.

Employers are seeing returns, too. As age diversity on work teams goes up, so does productivity and performance. Research from the Milken Institute’s Center for the Future of Aging and the Stanford Center on Longevity found that older employees took fewer sick days, showed stronger problem-solving skills, and were more likely to be highly satisfied at work than younger colleagues.

There exists a “gray ceiling” image—characterized by burnout, obsolescence, and career plateauing—that keeps many aging workers from reaching their potential. In the workplace, there is an clear age bias where recruiters favor younger applicants. You have only 5 years when most people are free of age bias—35-40. Otherwise, often you are viewed as either too young or too old.

The positive advantages of older workers are often ignored and rarely talked about. For example, studies of older workers in the workplace have shown that older workers engage in less unethical and/or criminal activity; have higher levels of participation in politics and volunteerism; have fewer workplace accidents; have better visual acuity; have less conflict with co-workers; have fewer power struggles; are less ego driven; have less health costs than younger workers; have greater loyalty to the organization; have more positive attitudes than younger workers; are more resilient under stress; do better quality work; have less job turnover; are more trainable and have a less net cost compared to younger workers.

Dorothy Leonard, professor of business administration, emerita, Harvard Business School and co-author of Deep Smarts: How to Cultivate and Transfer Enduring Business Wisdom, suggests companies focus on recreating tacit knowledge – experience, anecdotes and creative solutions – in the workplace. For example, if an experienced CPA is planning to retire, the firm where they work should allocate a younger accountant to work with them. Leanne Cutcher, professor of management and organization studies University of Sydney Business School, agrees: “External mentoring is valuable but it’s after the horse has bolted. Knowledge is useful in context.”

Americans age 50 and over who remain in the workforce tend to be more educated than younger people in the workforce. About 19 percent of employed workers over age 65 have a graduate degree, compared with about 13.5 percent of employed workers under 65. This higher level of education plus the fact that the work by older Americans is less physically demanding allows those over age 50 to remain longer in the workforce. Over the last 10 years people ages 55-64 made up the highest rate of entrepreneurs in the United States and one in three new businesses was started by an entrepreneur age 50 or more.

Challenges for the Workplace to Resolve

Since 1998, the US has seen employment rise by 22 million to reach historical highs. The main cause of this increase isn’t the dynamism of Silicon Valley or the entrepreneurial energy of Brooklyn hipsters. The vast majority (90%) of this increase is due to higher employment for workers aged 55 and above.

One specific barrier to older employment that receives much attention is corporate age discrimination. Older workers report frequent prejudice in terms of pay, promotion, training and recruitment. As the research of David Neumark of University California Irvine shows, workers over 60 who put their age on their CV halve their probability of being called for interview.

Businesses do not consider aging people a viable demographic market, community organizations labeled them recipients rather than contributors, and when they were included in commercials, movies or news segments, they are portrayed as unhealthy, unproductive and uninvolved: a burden on the economy and the younger generations.

In “The Big Shift: Navigating the New Stage Beyond Midlife”, Marc Freedman argues that we need a “new map of life” to deal with this powerful demographic change. Mr. Freedman is founder and chief executive of Civic Ventures, a nonprofit research group focused on boomers. He points out that while medical science, improved nutrition and other advances have succeeded in extending our lives, our ability to redefine these longer lives has lagged woefully behind. Freedman wants to broaden the way that people think about this part of life, which he calls the “encore stage.” The encore stage is not about “clinging to our lost youth,” he says. Rather, it means using one’s evolving identity and experience in ways that are characterized by “purpose, contribution and commitment, particularly to the well-being of future generations.”

Ellen Galinsky, President and Co-Founder of the Families and Work Institute says that companies need to recreate work places that are multigenerational and that will require rethinking how work is organized, including more flexible work-life arrangements.

Often, mature workers are left on their own as they near the end of their careers. Most organizations have no career development or professional growth plans for mature workers. A Manpower survey found that just 28% of U.S. companies and 21% of companies worldwide have a strategy for retaining mature workers. A study by the Conference Board showed that 80% of HR executives surveyed were oblivious to the concerns of older workers. An international study by Manpower showed that just 18% of U.S. employers have a strategy to recruit mature employees; Canada 17%; whereas Hong Kong 25% and Singapore, 48%.

There are some organizations doing something about the issue. Companies in Finland, where aging workers is a more significant issue, are taking action. For example, the Abloy lock company, which operates in 40 countries, has 30% of its workers over the age of 55. They have created the designation of Agemaster for these employees, and they are entitled to an assortment of benefits—massages, free memberships in health clubs, free education, all funded by the company, free complete physical exams and fitness tests, and an annual 5 week vacation. And the creation of a mentoring program where all mature workers pass on their knowledge to younger workers before they leave. Finland, which already is facing an aging workforce, has initiated the National Program on Ageing Workers, a 4 year campaign to change public attitudes. The core of that program is the view that work should be adapted to the abilities of aging workers, rather than the other way around.

Westpac Banking Corporation of Australia and New Zealand, recognized for its commitment to corporate social responsibly, made a commitment to attract mature workers. They have increased their average age of 45 of their workforce from 20% to 30% in just 5 years. They have found that absenteeism for mature workers is actually lower than for younger employees. They have also found a larger percentage of mature employees were rated as outstanding or above average in their work compared to employees younger than 45.

At a BMW factory in Germany, management realized workers were getting older. They estimated their employees would soon average age 47. BMW did not want to either force workers out, and many wanted to continue to work. They asked workers how could they make things better for them. Workers complained of sore feet from standing, so they made special shoes for them, and put in wooden floors instead of concrete, some got chairs, like a hairdresser. They adjusted work schedules to allow for stretching and relaxing; Tools and computer screens were changed to adapt to age. The entire project only cost BMW $50,000, and productivity and job satisfaction went up.

A study of top companies in Canada, as reported in the Globe and Mail, illustrated strategies they used to retain older employees, including: Additional vacation time up to 6 weeks; free training and tuition programs; phased in retirement; physical fitness and wellness centers on site; and academic scholarships for children and grandchildren.

Ageism Workplace Myths

The research exists, however, to challenge ageist myths in the workplace. In a study of productivity and workplace diversity, Researchers found that after factoring out machinery age in manufacturing establishments, productivity is no different in establishments with older versus younger workforces (as measured by the percent of workers older than age 50). Researchers conclude from a case study of employees working overtime at Navistar, Inc., a manufacturer of heavy trucks and diesel engines, that “adverse outcomes [from overtime]—and indirect costs—do not increase with advancing age in any kind of wholesale fashion.”

A case study of a Days Inn call center reveals that considering just one measure of productivity—time per call—resulted in older workers appearing less productive, as they took longer on average to complete each call received. However, measuring productivity as revenue generated revealed a positive association between age and productivity because older workers in the call center brought in more “revenue by booking more reservations than younger workers”.

And there are examples of companies who leverage older workers’ abilities and experience to strategic advantage in the marketplace. Mary Young’s Gray Skies, Silver Linings: How Companies Are Forecasting, Managing and Recruiting a Mature Workforce presents several synopses of companies, ranging from CVS/caremark pharmacy to the lock maker Abloy Oy, that have developed practices to engage and retain key talent found in older workers.

Ageism Government Policies

In reality, 70 percent of Americans older than age 65 will need some form of long-term care. This denial of the need for care is largely why there is no real funding for long-term care. To further deny the need for a comprehensive public−private partnership in long-term care is to perpetuate ageism—denial of growing old is ageist.

The older adults of today and tomorrow are the engines that will drive our economy and social capital of the future. The actions we take today and tomorrow are critical, as the population of those ages 65 and older is larger than at any time in history. A national advocacy agenda of the future must include the recognition that ageism exists and policies and programs must be evaluated from the context of reducing or furthering ageism. Changes that are proposed can either be small and incremental, or large and landmark in scope. We are a nation built on opportunity and progress. Ageism represses both and thus must be addressed for us to be a better society for all.

Healthcare System Responses to the Elderly

Studies have found that some physicians do not seem to show any care or concern toward treating the medical problems of older people. Then, when interacting with these older patients on the job, the doctors sometimes view them with disgust and describe them in negative ways, such as “depressing” or “crazy.” For screening procedures, elderly people are less likely than younger people to be screened for cancers and, due to the lack of this preventative measure, less likely to be diagnosed at early stages of their conditions. After being diagnosed with a disease that may be potentially curable, older people are further discriminated against. Though there may be surgeries or operations with high survival rates that might cure their condition, older patients are less likely than younger patients to receive all the necessary treatments. Furthermore, caregivers further undermine the treatment of older patients by helping them too much, which decreases independence, and by making a generalized assumption and treating all elderly as feeble. Differential medical treatment of elderly people can have significant effects on their health outcomes, a differential outcome which somehow escapes established protections.

Robert Butler wrote in Why Survive? Growing Old in America of a policy of pacification: the overuse in institutions of psychotropic drugs instead of “decent, humane attention through diagnosis and careful treatment

In contrast to a previous era, academic and professional research is now near the forefront of the fight against ageism. A model guiding much cutting-edge research is that of successful aging, which has replaced earlier models that attempted to map the dimensions of age deterioration through the flawed methodology of cross-sectional design. Successful aging shows similarities with health promotion and illness prevention paradigms that emphasize the identification of factors that promote autonomy and quality of life.

Self-Fulfilling Prophesy

Ageism has significant effects on the elderly and young people. These effects might be seen within different levels: person, selected company, whole economy. The stereotypes and infantilization of older and younger people by patronizing language affects older and younger people’s self-esteem and behaviors. After repeatedly hearing a stereotype that older or younger people are useless, older and younger people may begin to feel like dependent, non-contributing members of society. They may start to perceive themselves in terms of the looking-glass self—that is, in the same ways that others in society see them. Studies have also specifically shown that when older and younger people hear these stereotypes about their supposed incompetence and uselessness, they perform worse on measures of competence and memory. These stereotypes then become self-fulfilling prophecies.

Older people themselves can be deeply ageist, having internalized a lifetime of negative stereotypes about aging. Fear of death and fear of disability and dependence are major causes of ageism; avoiding, segregating, and rejecting older people are coping mechanisms that allow people to avoid thinking about their own mortality.

Aging is no longer viewed as a natural stage of life, but a horror and devastating progression. Why are we as a human race so set on reversing the inevitable? The war on aging is on, but has our America’s obsession gone too far? The statistics show that more and more women are getting facelifts, and they also show that women are becoming interested in the procedure at a younger age. Women are now getting facelifts even as young as in their thirties. According to a report by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, procedures such as plastic surgery, Botox and wrinkle fillers are up 100% percent since 2000.

Yet, and this is important, most of the studies of aging have focused on the 5% who are sick or diseased. Actually we have very few studies about physically and mentally healthy aging adults. Biogerentology, the biology of aging, is a science that is only 50 years old. One of the problems of our view of aging is our medical model which focuses on sickness instead of health. In contrast, the new advances in mind-body connection and neuroscience research show great promise in helping people with aging and maintaining good health.

The term “successful aging” has been used in the gerontological literature to cover processes of aging throughout the life span It implies positive aging processes for some while provoking criticisms of failing to be either not comprehensive enough or too far-reaching for others The term “successful aging” suggests “key ideas such as life satisfaction, longevity, freedom from disability, mastery and growth, active engagement with life, and independence” Sometimes successful aging has been called “vital aging” or “active aging” or “productive aging” with the implication that later life can be a time of sustained health and vitality where older people contribute to society rather than merely a time of ill health. The emphasis for many may be on maintaining positive functioning as long as possible but others have suggested that successful aging can also be discussed under more adverse health conditions.

Increased Demand for Services and Support Specifically for the Elderly

With the increase in the elderly population, there will be an increase in demand and the senior living industry will have to expand to meet that demand. Expect to see senior living communities popping up all over the country – not just in typical retirement states like Florida and Arizona. Many seniors are moving away from these states and halfway back to their home states, even inventing a new retirement term, “halfbacks.” As the demand for senior living increases, senior communities will rise in rural and urban settings alike.

Not only will there be more senior living options, but they will look a little different. Today’s baby boomers expect more when it comes to senior living and senior care. They want accessibility and convenience partnered with unmatched care and amenities. The future of senior living is not institutional. It’s vibrant and active, encouraging and empowering – reflecting a generation that has changed their nation.

As demand for senior living grows and the boomer generation raises the standard on senior living, we can expect to see more options and personalized care. From concierge services to transportation and even customized care offerings, senior living in the future will continue to move away from institutional care toward a true sense of home and community.

Of primary importance for the aging will be the issue of appropriate medical and support care. As the number of senior people rises in many economies of the world, the need for long-term care and aging-in-place services will increase. This will escalate the burden on healthcare in many countries. There are some interesting models that are arising to meet the needs of this population. Many of these models are experiments, but they are proving to be highly successful in providing care, reducing cost and improving quality of life to this silver community.

As people live longer, there will be a sharp increase in the number of people with dementias, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). In fact, 25% to 30% of people aged 85 and older have a high level of cognitive decline. Globally there are an estimated 47.5 million dementia sufferers, and the number is expected to increase to 75.6 million by 2030 and 135.5 million by 2050. European countries with significant prevalence of dementia are Germany (1.9%) and Italy (2.09%). AD is the most common form of dementia, affecting an estimated 5 million people older than 65 in the U.S.

Countries like Japan are struggling to move from hospital-centered medical care to community-oriented medical care. With declining birth rates and an increasing elderly population (people aged ≥65 years reached 25% in 2013 and is expected to exceed 30% in 2025 and 39.9% in 2060), Japan has invested heavily in robotics and is one of the first countries to be ready with products or prototypes in 2015. South Korea, the U.K., Germany, and China are closely behind in terms of manufacturing. These robots are ready to become part of the household soon. The question is, are seniors ready to share their house with a robot?

The nursing robot, “Robear,” is an experimental nursing-care robot developed by the RIKEN-SRK Collaboration Center for Human-Interactive Robot Research and Sumitomo Riko Company. It can work as a nursing robot and can perform tasks like lifting patients from wheelchairs. Robear can become an alternative for nurses in care homes and independent homes. Currently, nursing homes are struggling with manpower shortage. These robots can help seniors manage their day-to-day activities in their own homes. Another example is Care Robot or “ChihiraAico” robot, which resembles a Japanese woman and is likely to be used to assist elderly people with conditions, like dementia, by connecting them to medical staff.

Robo Chef has been programmed to assemble and chop ingredients, using the stove or oven to cook, and later can also finish up by cleaning the dirty dishes. The Robo Chef is expected to enter the market between 2017 and 2018 at a cost of $10,967 and can become a great support for elders living in their homes and who are unable to do some household chores.

If Transformers from the movie can become a reality, then Giraffplus would definitely be one of them. These remote-controlled bots can connect elderly patients with their friends and family, as well as facilitate a virtual visit. At the same time, it comes with sensors outfitted around the home tracking where someone is and what they’re doing. These robots can transform into their social friends by connecting them with their loved ones through the Internet.

A Melbourne, Australia nursing home is using robots to interact and play games with residents, as well as improve the quality of life of patients with dementia. Baby seal Palro, expected to be priced at $8,600, is an interactive model developed in Japan. This robot already passed a successful trial in 2014. With the U.S. moving toward becoming a super-aged nation, will Americans be open to adopting Palro? SoftBank’s Pepper has got its work visa and also would be available for service in the commercial market. Who is next?

The shrinking oldest-old support ratio is raising a lot of concerns at the highest level in terms of policy and also on the ground–people are asking “Who’s going to be taking care of grandma or grandpa?”. There are ongoing discussions and research about different models of care, and I don’t think we have any easy solutions at this time. Clearly there’s a lot of research and interest in trying to improve active life expectancy. The goal is not necessarily to increase longevity, but to increase independent function until as late in life as possible so that the person only needs hands-on care for a very short period of time prior to their death.

The U.S. federal social security system functions through the taxation of large numbers of young workers, in order to support smaller numbers of older dependents. A diminishing workforce, coupled with growing numbers of longer-living elderly can deplete the social security system. The U.S. Social Security Administration estimates that the old age dependency ratio (people ages 65+ divided by people ages 20–64) in 2080 will be over 40%, compared to the 20% old age dependency ratio in 2005.Increasing life expectancies of the older population will not only result in decreases in Social Security Benefits, but also devalues private and public pension programs. The threat of cutbacks to Social Security and Medicare, as a result of a shortfall in funding, may be a contributing factor for adults to delay retirement and to continue working.

What Actions Are Necessary?

In a recent article published in The Elder Law Journal, Sharona Hoffman, the Edgar A. Hahn Professor of Law at the Case Western Reserve University School of Law, urges policymakers to focus on the elderly population. “Everyone ages, and everyone has aging loved ones, so this is a personal issue for most of us, even if we don’t want to think about it,” she states.

“In 2016, voters listed terrorism as their first and most serious national concern, but only 80 Americans were killed in terrorist attacks between 2004 and 2013, while millions of individuals faced grave difficulties related to aging,” said Hoffman, author of Aging with a Plan: How a Little Thought Today Can Vastly Improve Your Tomorrow.

Hoffman offered five specific suggestions to improve conditions for seniors as their numbers continue to increase:

- Advocacy organizations and the media should educate the public and policy-makers about the challenges the elderly face and strive to make them a political priority.

- Long-term care (home care from aides, assisted living, and nursing homes) must become more accessible and affordable. This could be achieved through long-term care insurance that is subsidized by the government.

- The working conditions of professional caregivers must be significantly improved. Consider wage increases, health benefits and paid sick days.

- Affordable transportation options should be available to the elderly so they don’t lose their independence if and when they stop driving.

- Incentives, such as loan forgiveness programs and higher Medicare payments, should be offered to prospective health-care professionals as encouragement to enter the geriatric field.

We remain stubbornly wedded to ageism, despite numerous efforts to address cultural and social biases that undermine our society and economy. Ageism is so well integrated into our thinking and social mores that we are almost incapable of seeing it. Self-directed ageism (an internalized bias against ourselves) is no less prevalent than its external counterpart. Until and unless we address it, we will miss out on opportunities to position itself well both economically and socially for the future.The presence of substantial numbers of older people offers societies a resource that has never before existed—millions of experienced, wise, older citizens who are healthier and better educated than any previous generation. To allow all individuals the opportunities to age successfully, it is crucial to combat ageism in workplace structures and policies, beliefs about aging that discourage interventions, and research practices that conflate normal aging with disease states. We must not aim too low. By addressing these issues, we can revise knowledge about aging and begin to redesign the life course to reap the individual and societal benefits that longer lives represent.

We need a new kind of clock: a Ulyssean model in which the later years are viewed as a time of wisdom, creativity, power and purpose. We need to make a distinction among job, career and life calling. For people who are aging, calling is far more important. Look at the state of the world now, and what cognition has brought us without wisdom.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest books:

- I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.

- Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle onAmazonandBarnes & Noble world-wide..