By Ray Williams,

February 25, 2021

You’ve reached a roadblock on a project at work, so you go home in frustration. While cooking dinner, you suddenly figure out a solution to the obstacle you left at the office. You’ve had an “aha moment,” and it’s the underappreciated path to creativity and productivity.

We’ve all experienced those times when a sudden occurrence makes our eyes widen, heart quicken, gut contract, and awareness sharpen—any or all of which signify that whatever we’re encountering, or feeling, is potentially new or meaningful. And so, this (whatever this is), demands our attention. An “AHA!” moment can hit without warning, or come about after prolonged deliberation, but it can be the start of something marvelous—a flash that leads to a visionary idea, an exciting adventure, a solution to a problem, a collaborative endeavor, or an act of kindness. It may also be the impetus for creative expression.

Definition: “A sudden comprehension that solves a problem, reinterprets a situation, explains a joke, or resolves an ambiguous percept is called an insight (i.e., the ‘‘Aha! moment’’). The Aha moment has also been described as insight, intuition, epiphany and “eureka!”

History and Etymology

The Aha moment or eureka is named from a story about ancient Greek polymath Archimedes. In the story, Archimedes was asked (c. 250 BC) by the local king to determine whether a crown was pure gold. During a subsequent trip to a public bath, Archimedes noted that water was displaced when his body sank into the bath, and particularly that the volume of water displaced equaled the volume of his body immersed in the water. Having discovered how to measure the volume of an irregular object, and conceiving of a method to solve the king’s problem, Archimedes allegedly leaped out and ran home naked, shouting εὕρηκα (eureka, “I have found it!”). This story is now thought to be fictional, because it was first mentioned by the Roman writer Vitruvius nearly 200 years after the date of the alleged event, and because the method described by Vitruvius would not have worked.

Modern research on the Aha! moment dates back more than 100 years, to the Gestalt psychologists’ first experiments on chimpanzee cognition. In his 1921 book, Wolfgang Köhler described the first instance of insightful thinking in animals: One of his chimpanzees, Sultan, was presented with the task of reaching a banana that had been strung up high on the ceiling so that it was impossible to reach by jumping. After several failed attempts to reach the banana, Sultan sulked in the corner for a while, then suddenly jumped up and stacked a few boxes upon each other, climbed them and thus was able to grab the banana. This observation was interpreted as insightful thinking. Köhler’s work was continued by Karl Duncker and Max Wertheimer.

The Eureka effect was later also described by Pamela Auble, Jeffrey Franks and Salvatore Soraci in 1979. The subject would be presented with an initially confusing sentence such as “The haystack was important because the cloth ripped”. After a certain period of time of non-comprehension by the reader, the cue word (parachute) would be presented, the reader could comprehend the sentence, and this resulted in better recall on memory tests. Subjects spend a considerable amount of time attempting to solve the problem, and initially it was hypothesized that elaboration towards comprehension may play a role in increased recall.

Examples of Aha Moments

There are several examples of scientific discoveries being made after a sudden flash of insight. One of the key insights in developing his special theory of relativity came to Albert Einstein while talking to his friend Michele Besso: “I started the conversation with him in the following way: “Recently I have been working on a difficult problem. Today I come here to battle against that problem with you.” We discussed every aspect of this problem. Then suddenly I understood where the key to this problem lay. Next day I came back to him again and said to him, without even saying hello, “Thank you. I’ve completely solved the problem.”

However, Einstein has said that the whole idea of special relativity did not come to him as a sudden, single eureka moment, and that he was “led to it by steps arising from the individual laws derived from experience”. Similarly, Carl Friedrich Gauss said after a eureka moment: “I have the result, only I do not yet know how to get to it.”

Sir Alec Jeffreys had a eureka moment in his lab in Leicester after looking at the X-rayfilm image of a DNA experiment at 9:05 am on Monday 10 September 1984, which unexpectedly showed both similarities and differences between the DNA of different members of his technician’s family Within about half an hour, he realized the scope of DNA profiling, which uses variations in the genetic code to identify individuals. The method has become important in forensic science to assist detective work, and in resolving paternity and immigration disputes. It can also be applied to non-human species, such as in wildlife population genetics studies. Before his methods were commercialized in 1987, Jeffreys’ laboratory was the only center carrying out DNA fingerprinting in the world.

Here are some other examples:

- GoPro founder who struggled to take a picture of himself while surfing.

- Ikea founder could not fit a table in his small car, so he thought to take off the legs.

- Samuel Morse received a letter about his wife’s illness after she was already buried. Letters took a long time back then. He raced to see her, but it was too late. Grief-stricken, he decided to forever change how people talk to each other and invented the telegraph.

Why the Aha Moment is Important

Insight is a sudden comprehension—colloquially called the ‘‘Aha! moment’’—that can result in a new interpretation of a situation and that can point to the solution to a problem. Insights are often the result of the reorganization or restructuring of the elements of a situation or problem, though an insight may occur in the absence of any preexisting interpretation.

For several reasons, insight is an important phenomenon. First, it is a form of cognition that occurs in a number of domains. For example, aside from yielding the solution to a problem, in- sight can also yield the understanding of a joke or metaphor, the identification of an object in an ambiguous or blurry picture, or a realization about oneself. Second, insight contrasts with the deliberate, conscious search strategies that have been the focus of most research on problem solving; instead, aha moments occur when a solution is computed unconsciously and later emerges into awareness suddenly. Third, because insight involves a conceptual reorganization that results in a new, nonobvious interpretation, it is often identified as a form of creativity. Fourth, insights can result in important innovations. Understanding the mechanisms that make insights possible may lead to methods for facilitating innovation.

It may not appear in the shape of a light bulb above your head, but researchers say “Aha!” moments are marked by a surge of electrical activity in the brain.

What brings the Aha moment?

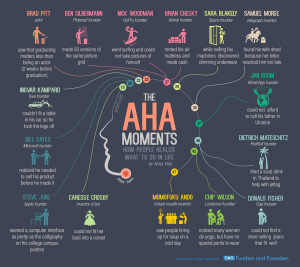

The Aha moment comes at different ages. Here are a few examples. Is it ever too late to have the aha moment? Some entrepreneurs had them well into their fifties. Were they thinking it was never too late?

Some research describes the Aha! effect (also known as insight or epiphany) as a memory advantage, but conflicting results exist as to where exactly it occurs in the brain, and it is difficult to predict under what circumstances one can predict an Aha! moment.

Insight is a psychological term that attempts to describe the process in problem solving when a previously unsolvable puzzle becomes suddenly clear and obvious. Often this transition from not understanding to spontaneous comprehension is accompanied by an exclamation of joy or satisfaction, an Aha! moment. A person utilizing insight to solve a problem is able to give accurate, discrete, all-or-nothing type responses, whereas individuals not using the insight process are more likely to produce partial, incomplete responses.

A recent theoretical account of the Aha! moment started with four defining attributes of this experience. First, the Aha! moment appears suddenly; second, the solution to a problem can be processed smoothly, or fluently; third, the Aha! moment elicits positive affect; fourth, a person experiencing the Aha! moment is convinced that a solution is true. These four attributes are not separate but can be combined because the experience of processing fluency, especially when it occurs surprisingly (for example, because it is sudden), elicits both positive affect and judged truth.

Insight can be conceptualized as a two phase process. The first phase of an Aha! experience requires the problem solver to come upon an impasse, where they become stuck and even though they may seemingly have explored all the possibilities, are still unable to retrieve or generate a solution. The second phase occurs suddenly and unexpectedly. After a break in mental fixation or re-evaluating the problem, the answer is retrieved. Some research suggest that insight problems are difficult to solve because of our mental fixation on the inappropriate aspects of the problem content. In order to solve insight problems, one must “think outside the box”. It is this elaborate rehearsal that may cause people to have better memory for Aha! moments. Insight is believed to occur with a break in mental fixation, allowing the solution to appear transparent and obvious.

There was no evidence that elaboration had any effect for recall. It was found that both “easy” and “hard” sentences that resulted in an Aha! effect had significantly better recall rates than sentences that subjects were able to comprehend immediately. In fact, equal recall rates were obtained for both “easy” and “hard” sentences which were initially incomprehensible. It seems to be this non-comprehension to comprehension which results in better recall.

The Research

Brain Research

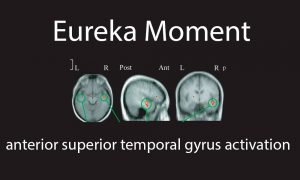

fMRI and electroencephalogram studieshave found that problem solving requiring insight or the aha moment involves increased activity in the right cerebral hemisphere as compared with problem solving not requiring insight. In particular, increased activity was found in the right hemisphere anterior superior temporal gyrus.

A study with the goal of recording the activity that occurs in the brain during an Aha! moment using fMRIs was conducted in 2003 by Jing Luo and Kazuhisa Niki. Participants in this study were presented with a series of Japanese riddles, and asked to rate their impressions toward each question using the following scale: (1) I can understand this question very well and know the answer; (2) I can understand this question very well and feel it is interesting, but I do not know the answer; or (3) I cannot understand this question and do not know the answer. This scale allowed the researchers to only look at participants who would experience an Aha! moment upon viewing the answer to the riddle. In previous studies on insight, researchers have found that participants reported feelings of insight when they viewed the answer to an unsolved riddle or problem. Luo and Niki had the goal of recording these feelings of insight in their participants using fMRIs. This method allowed the researchers to directly observe the activity that was occurring in the participant’s brains during an Aha! moment. An example of a Japanese riddle used in the study: The thing that can move heavy logs, but cannot move a small nail→A river.

Participants were given 3 minutes to respond to each riddle, before the answer to the riddle was revealed. If the participant experienced an Aha! moment upon viewing the correct answer, any brain activity would be recorded on the fMRI. The fMRI results for this study showed that when participants were given the answer to an unsolved riddle, the activity in their right hippocampus increased significantly during these Aha! moments. This increased activity in the right hippocampus may be attributed to the formation of new associations between old nodes. These new associations will in turn strengthen memory for the riddles and their solutions.

A new study shows that solving a problem that requires creative insight prompts distinct changes in brain activity that don’t occur under normal problem-solving conditions.

“For thousands of years people have said that insight feels different from more straightforward problem solving,” says researcher Mark Jung-Beeman, an associate professor of psychology at Northwestern University, in Evanston, Ill. in a news release. “We believe this is the first research showing that distinct computational and neural mechanisms lead to these breakthrough moments.”

In the study, which appears in the April issue of PloS Biology, researchers compared brain activity in two different experiments.

In the first, study participants were given a series of word problems to solve designed to evoke a distinct “Aha!” moment about half the time they were solved. Using brain imaging techniques, researchers found that activity increased in a small part of the right lobe of the brain called the temporal lobe when the participants reported experiencing creative insight during problem solving. Little activity was detected in this area during non-insight solutions.

Researchers say previous studies have shown that this right temporal lobe may be important for drawing distantly related information together, which is a key component of insight.

In the second experiment, researchers monitored the participants’ brainwave activity using an electroencephalogram (EEG) during insight and non-insight problem solving tasks.

The study showed that about one-third of a second before the “Aha!” moment, there was a sudden burst of high-frequency brain waves. This type of activity is associated with high-level processing of information, and researchers say it was also centered in the same right temporal lobe area.

In addition, a second smaller wave of electrical activity was seen on EEG. About 1.5 seconds before the moment of insight, there was an increase in lower frequency brain waves in this area of the brain, which disappeared when the high-frequency activity began.

Researchers say this “gating” effect might occur to allow weak solution-related activity to gain momentum and then burst into consciousness as insight.

“This is like closing your eyes so you can concentrate when you are trying to solve a difficult problem,” says researcher John Kounios of Drexel University in a news release. “But in this case, your brain is blocking out just the visual inputs to your right hemisphere.”

Researchers say that these clues may help scientists better understand the creative insight process and its impact on the brain.

In a pair of studies, psychological scientists Shelly L. Gable, Elizabeth A. Hopper, and Jonathan Schooler recruited two types of people whose livelihoods depend on innovation—theoretical physicists and professional writers. The first study involved 45 physicists at a research institute and 53 writers — including screenwriters, novelists, and nonfiction writers. Every evening over a 2-week period, the participants received a survey email that asked about any creative idea they had related to their profession and what they were doing when they had the idea. Specifically, they reported whether they were working on the problem at hand, on another work-related problem, or on something unrelated to work (such as paying bills).

In addition, participants reported whether the idea related to some kind of impasse or ongoing project, and whether it felt like an “aha” moment. Lastly, they rated the level of creativity and importance of the idea.

About 6 months later, the participants received a follow-up survey containing the ideas that they had listed in the earlier surveys. Once again, they rated each idea’s level of creativity and importance.

The second study followed the same procedure, but with a slightly smaller number of participants and a follow-up survey at 3 months instead of 6.

Across the two studies, participants reported that about 20% of their most important ideas occurred when they were thinking about something else, and they rated the ideas as being as equally important and creative as those formed while they were working on task.

In the follow-up surveys, the participants rated their previous ideas as slightly more creative, but less important, compared with their earlier ratings. Overall, they were more likely to rate ideas generated during mind wandering as the coveted “aha” moments compared with ideas generated while working.

Summary:

Our work (and personal) culture today emphasizes persistent focused activity for extended hours to solve a problem or make a decision. Yet, the research described above shows that often breakthroughs, solutions and creative ideas often come when we are away from our tasks, often doing something totally unrelated, and in many cases, in a leisure or pleasant activity.

Read my latest book:I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.