We’ve all seen, read about or worked with bad leaders—toxic, abusive or incompetent. And research (including mine) has described in detail their traits and faults. But what about the opposite? There are fewer stories and examples of good leaders where they are not described only in terms of their accomplishments, or bottom-line results or in some cases, their narcissistic extroverted personalities but are examples of virtuous traits and good character.

Recent research has focused more on the nature of leaders of good character. Which has also prompted me to write my book, Virtuous Leadership: The Character Secrets of Great Leaders.

In an article in MIT’s Sloan Management Review, authors Mary Crossan, William (Bill) Furlong and Robert D. Austin argue “For all of the attention that leader character gets when we witness its negative extremes — such as when an authoritarian CEO presides over a corrupt or an abusive culture — most organizations give surprisingly little thought to what is one of the most significant available levers to effect positive organizational development. Organizations that fail to hire for and develop positive character among its leaders are missing an opportunity.”

Fred Kiel’s study, published by Harvard Business Review found that organizations with leaders of high character — those whose employees rated them highly on integrity, responsibility, forgiveness, and compassion — had nearly five times the return on assets of those with low character.

Crossan and her colleagues ask the question: “Why is this aspect of leadership and organizational culture so overlooked? Over more than a decade of investigating leader character in organizations, we’ve found that leaders largely underestimate and misunderstand the concept of character. They marginalize it as just being about ethics rather than recognizing it as the foundation of all judgment and decision-making. They generally assess their character as ‘good enough.’ They believe it is a fixed trait rather than a quality that can be developed, and so they don’t see how individual strength of character can be embedded and scaled in their organizations and cultures. Simply put, they don’t see that competence and character go hand in hand.”

The authors explain that the impact of character on judgement and the decisions we make every day, minute by minute — or what they refer to as the micro-moments between stimulus and response — is the fundamental tenet of what character is and how it functions. Superior performance is supported by this character-based judgement, and its absence explains both wrongdoing and bad decision-making. Technical proficiency was mostly visible, but character was not in several high-profile incidents, including the 2008 global financial crisis, the Volkswagen emissions scandal, and the tragedy involving the Boeing 737 Max. In essence, the seeds of compromised character can be used to identify the precipice of compromised judgement and decision-making.

Crossan and her colleagues argue that it’s critical to remember that, while character strength undoubtedly aids in ethical decision-making, its application is far broader than that; as was mentioned above, too many leaders mistakenly associate it only with being “good,” which is far too limited. It is important at all levels of the business, not just in leadership because it has a significant impact on individual well-being and sustained excellence.

The Research

Crossan et al. interacted with more than 2,000 executives using focus groups and quantitative analysis to come up with a definition of leader character based on 10 separate dimensions which interact with a central 11th, “judgment,” which they titled “Leader Character Framework.”

Figure 1: The Leader Character Framework

The authors argue that contrary to popular opinion, character does not necessarily develop early in life or at birth. The fundamental truth is that character can be enhanced, but it may also atrophy without conscious attention to its growth. While we are engaged in doing what we do, we are constantly changing; we may grow more or less fearless, or more or less humble. Numerous studies have thus far demonstrated that as executives advance within an organization, hubris may set in (a lack of humility).

Taking Action

Individuals must take action based on the knowledge of their virtues, but leaders are also in charge of implementing an organizational-wide strategy for enhancing character and fusing it with competence. This entails giving the cultural norms of an organization a close examination since they may favour some character traits over others. According to psychologist Philip Zimbardo, who conducted the well-known Stanford jail experiment, occasionally troublesome behaviours are not caused by “a few rotten apples,” but rather by good apples being put into rotten barrels. Because character has been misunderstood and neglected, organizational barrels have continually given some character traits more weight than others. They have also failed to systematically integrate competence and character in leadership practices.

Organizational excellence and well-being will be the result when people have a greater awareness of what makes a good leader and take responsibility for improving their character in addition to their professional skills. However, when businesses hire, reward, and promote people with weak or unbalanced characteristics, they continue to have limited positive influence on their policies and practices. The good apples will eventually decide to leave the bad barrels because once people understand how to display leader character, they cannot “unsee” it.

Crossan et al. suggest that although leader character work has a broad strategic aim, there are real-world applications. Start with yourself first. Think about where your character needs to be strengthened and whether any potential virtues are acting more like vices. While you are busy, stop to think about whom you are becoming. How is your character manifesting for you, and how is it affecting others? One executive the authors know sets his watch multiple times a day to remind him to check on how his character is being activated to affect both his own and those around him. Many conversations that were heading in the wrong direction were redirected when people asked themselves, “What dimension of character do I need to engage at this moment?”

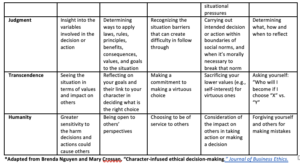

Asking Questions of Yourself Using Dimensions of Virtuous Character

The following chart (2 pages) can be a useful reference for leaders in cross-referencing leadership virtues of good character with the key elements of awareness, judgment, intent, behavior and reflection.

Crossan et al. emphasize the importance of their research by arguing “Finally, our aim has been to enable the strategic shift in elevating character alongside competence with a far-ranging set of tools, from articles and podcasts to assessment instruments and learning apps. It’s a big idea and a profound shift, but there are very practical tools and approaches to help implement it. We contend that the times we live in make elevating character alongside competence not only a strategic imperative but also a social responsibility.”

You can read a lot more about emphasizing the importance of good character in leadership in my book Virtuous Leadership: The Character Secrets of Great Leaders.