By Ray Williams

June 20, 2020

The current pandemic and economic crises have forced many people into isolation, and in many cases inactivity—both voluntary and forced. While it may sound crazy to consider that slowing down and occasionally doing nothing if your social and financial life has been turned upside down, consider that the current situation may provide us with an opportunity to reconsider our commitment to busy and “productive” lives, even if it is involuntarily.

Let me explain.

Before COVID-19 and it’s accompanying financial crunch for many people, we were accustomed to a super busy life on doing more and more faster and faster. And examples of hyperactive and successful people were often thrust in our faces by the media.

Our Hyper connected Fast-Paced, Overworked Life

Examples of the workaholic, rapid decision makers are constantly presented to us as the model to follow. Here’s some examples:

- Virgin Group founder Richard Branson, for instance gets up at 5 a.m. every day. He answers emails, eats breakfast with his family, reads the news, takes meetings and plays sports like tennis, running and kitesurfing — all before going to bed at 11 p.m.

- Elon Musk himself is renowned for 100-hour workweeks, little sleep and years without a vacation.

- Apple CEO Tim Cook is famously a workaholic. He reportedly sends regular work emails at 3:45 a.m., runs weekly office meetings for five hours and barely has a social life. A profile in Gawker reveals that he’s the first in the office and the last to leave. He used to hold staff meetings on Sunday night in order to prepare for Monday.

- Billionaire Mark Cuban wrote in his blog when he started his first company, he routinely stayed up until 2 a.m.reading about new software, and went seven years without a vacation.

- In his early days at Amazon’s Jeff Bezos’ work was characterized by working 12-hour days, seven days a week, and being up until 3 a.m. to get books shipped.

- Nissan and Renault CEO Carlos Ghosn worked more than 65 hours a week, spent 48 hours a month in the air, and flew more than 150,000 miles a year.

- Marissa Mayer routinely pulled all-nighters and worked 130-hour weeks while at Google, a schedule she managed by sleeping under her desk.

- GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt spent 24 years putting in 100-hour weeks.

Sociologist Juliet Schor notes in her book, The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure, notes, Americans are overworked, putting in more hours than at any time since the Depression and more than in any other in Western society.

Instant and constant access has become de rigueur, and our devices constantly expose us to a barrage of colliding and clamoring messages: “Urgent,” “Breaking News,” “For immediate release,” “Answer needed ASAP.”

Our leisure time, our family time — even our consciousness—is constantly interrupted and disturbed.

Simon Gottschalk, in his book, The Terminal Self: Everyday Life in Hypermodern Times,describes the social and psychological effects of our growing interactions with new information and communication technologies. In this 24/7, “always on” age, the prospect of doing nothing or slowing down might sound unrealistic and unreasonable, he says.

In an age of incredible advancements that can enhance our human potential and planetary health, why does daily life seem so overwhelming and anxiety-inducing?

It’s a complex question, but one way to explain this irrational state of affairs is something called the force of acceleration.

According to German critical theorist Hartmut Rosa, author of Social Acceleration: A New Theory of Modernity,accelerated technological developments have driven the acceleration in the pace of change in social institutions.

We see this on factory floors, where “just-in-time” manufacturing demands maximum efficiency and the ability to nimbly respond to market forces, and in university classrooms where computer software instructs teachers how to “move students quickly” through the material. Whether it’s in the grocery store or in the airport, procedures are implemented, for better or for worse, with one goal in mind: speed.

Noticeable acceleration began more than two centuries ago, during the Industrial Revolution. But this acceleration has itself accelerated. Guided by neither logical objectives nor agreed-upon rationale, propelled by its own momentum, and encountering little resistance, acceleration seems to have begotten more acceleration, for the sake of acceleration.

To Rosa, this acceleration eerily mimics the criteria of a totalitarian power: 1) it exerts pressure on the wills and actions of subjects; 2) it is inescapable; 3) it is all-pervasive; and 4) it is hard or almost impossible to criticize and fight. Does this acceleration account for the spread of dictators including wannabe ones like Donald Trump?

Unchecked acceleration has consequences.

At the environmental level, it extracts resources from nature faster than they can replenish themselves and produces waste faster than it can be processed.

At the personal level, it distorts how we experience time and space. It deteriorates how we approach our everyday activities, deforms how we relate to each other and erodes a stable sense of self. It leads to burnout at one end of the continuum and to depression at the other. Cognitively, it inhibits sustained focus and critical evaluation. Physiologically, it can stress our bodies and disrupt vital functions.

For example, Diane Perrons’ edited book, Gender Divisions and Working Time in the New Economy describes research finds two to three times more self-reported health problems, from anxiety to sleeping issues, among workers who frequently work in high-speed environments compared with those who do not.

When our environment accelerates, we must pedal faster in order to keep up with the pace. Workers receive more emails than ever before — a number that’s only expected to grow. The more emails you receive, the more time you need to process them. It requires that you either accomplish this or another task in less time, that you perform several tasks at once, or that you take less time in between reading and responding to emails.

American workers’ productivity has increased dramatically since 1973. What has also increased sharply during that same period is the pay gap between productivity and pay. While productivity between 1973 and 2016 has increased by 73.7 percent, hourly pay has increased by only 12.5 percent. In other words, productivity has increased at about six times the rate of hourly pay.

Clearly, acceleration demands more work — and to what end? There are only so many hours in a day, and this additional expenditure of energy reduces individuals’ ability to engage in life’s essential activities: family, leisure, community, citizenship, spiritual yearnings and self-development.

It’s a vicious loop: Acceleration imposes more stress on individuals and curtails their ability to manage its effects, thereby worsening it.

Today’s hectic, fast paced and overstimulated world can create a work and lifestyle of hurriedness, busyness, multitasking and workaholism, all aimed at increasing productivity and life satisfaction. Yet, there’s compelling evidence that slowing down can actually improve productivity and increase happiness.

I’m sure many of you share my experience of going on vacation for relaxation. Our pace slows down, we usually feel more calm and relaxed, and we take a much needed respite from our fast pace of life and its responsibilities. Time slows down. Yet when we return from work, that calm, slower pace disappears and we’re back on the hamster wheel.

— Image by © Ben Welsh/Design Pics/Corbis

Myths About “More and Faster”

While it is conventional wisdom in the workplace and management reinforces the “more is better” “and faster is better” approach to work, the assumptions are not supported by research. Let’s look at these myths:

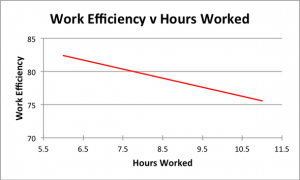

Myth 1: More hours of work make you more productive

We now equate busyness and overwork with productivity but the two are not the same. In the same way, we’ve equated “seat time” –that is time workers spend in their seats at their desks or in meetings–as equivalent to productive work. It may be the reverse. In a New York Times article, “Let’s Be Less Productive,” author Tim Jackson defines productivity as “the amount of output delivered per hour of work in the economy.” Jackson’s view underscores the perception that productivity in all its forms is measured in terms of money and time. Jackson goes on to say, “time is money…We’ve become conditioned by the language of efficiency.”

Sara Robinson, in her insightful article in Salon magazine, argues the following on the issue of overwork: “Bring Back the 40-hour Work Week,” adding, “150 years of research proves that long hours at work will kill profits, productivity and employees.” Yet, for most of the 20th century, the broad consensus among American business leaders was that working people more than 40 hours a week was “stupid, wasteful, dangerous and expensive—and the most telling sign of dangerously incompetent management,”

Robinson argues. Citing the work of Tom Walker of the Work Less Institute’s Prosperity Covenant, “That output does not rise or fall in direct proportion to the number of hours worked is a lesson that seemingly has to be learned each generation.”

A Business Roundtable studyfound that after just eight 60-hour weeks the fall-off in productivity is so marked that the average team would have actually gotten just as much done and been better off if they’d just stuck to a 40-hour week all along. And at 70-or 80- hour weeks, the fall-off happens ever faster; at 80 hours, the break-even point is reached in just three weeks.

According to a study of 85,000 people in the European Heart Journal, long working days can increase the odds of you having a stroke.

Research by the US military has shown that losing just one hour of sleep per night for a week will cause a level of cognitive degradation equivalent to a .10 blood alcohol level. Worse: most people who’ve fallen into this state typically have no idea of just how impaired they are. It’s only when you look at the dramatically lower quality of their output that it shows up.

It’s not as though we need to work so hard. As Alex Soojung-Kim Pan, author of REST: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less, writes in Nautilus, luminaries including Charles Dickens, Gabriel García Márquez, and Charles Darwin had quite relaxed schedules, working for five hours a day or less. The truth is, work expands to fill the time it’s given and, for most of us, we could spend considerably fewer hours at the office and still get the same amount done.

“There’s an idea we must always be available, work all the time,” says Michael Guttridge, a psychologist who focuses on workplace behavior. “It’s hard to break out of that and go to the park.” But the downsides are obvious: We end up zoning out while at the computer—looking for distraction on social media, telling ourselves we’re “multitasking”while really spending far longer than necessary on the most basic tasks.

Plus, says Guttridge, we’re missing out on the mental and physical benefits of time spent focused on ourselves. “People eat at the desk and get food on the computer—it’s disgusting. They should go for a walk, to the coffee shop, just get away,” he says. “Even Victorian factories had some kind of rest breaks.”

Myth 2: Being Busy Improves Productivity and Happiness

“If you live in America in the 21st century you’ve probably had to listen to a lot of people tell you how busy they are. It’s become the default response when you ask anyone how they’re doing,” contends Tim Kreider in his article, “The Busy Trap,” in the New York Times. He says often this is said as a boast, “disguised as a complaint,” but often these same people complain about being dead tired and exhausted.

Kreider argues that overly busy people are busy because “of their own ambition or drive or anxiety, because they’re addicted to busyness and read what they might have to face in its absence…They feel anxious and guilty when they aren’t either working or doing something to promote their work.” He says that busyness serves as a kind of “existential reassurance, a hedge against emptiness.” For busy people’s lives cannot possibly be “silly or trivial or meaningless” if they are completely booked with activities, and “in demand every hour of the day.”

Krieder contends that our culture has assumed a value position that idleness or doing nothing is a bad thing. But “idleness is not just a vacation, an indulgence or a vice,” he says, “it is as indispensable to the brain as vitamin D is to the body, and deprived of it we suffer a mental affliction as disfiguring as rickets.

U.S.A. Today published a multi-year poll to determine how people perceived time and their own busyness. It found that in each consecutive year since 1987, people reported that they are busier than the year before, with 69 % responding that they were either “busy,” or “very busy,” with only 8 % responding that they were “not very busy.”

I work as an executive coach and advisor to many senior executives and professionals. Almost without exception they either complain or observe that they can “barely keep up,” or “have no time for vacations,” not time to do things for fun, and that their families often suffer. The result is often that they are overstressed and overworked, but tell me there is no choice—the job requires it. Telling people you are really busy has become some kind of a badge of courage, and people who are not so busy are looked down upon.

Even children today are over scheduled. Today’s adolescents and teens are overtaxed and overburdened and stressed to a degree that was once seen only in child psychiatric patients, according to an analysis of research spanning five decades by Jean Twenge, PhD, a psychology professor at San Diego State University.

Alvin Rosenfeld, M.D., a child psychiatrist and author of The Over-Scheduled Child: Avoiding the Hyper-Parenting Trap,“Overscheduling our children is not only a widespread phenomenon, it’s how we parent today,” he says. “Parents feel remiss that they’re not being good parents if their kids aren’t in all kinds of activities. Children are under pressure to achieve, to be competitive. I know sixth-graders who are already working on their resumes so they’ll have an edge when they apply for college.”

Increasingly, management in organizations are concerned about productivity and regularly assess employee engagement levels. But the problem with this approach is that engagement is associated with “seat time.” A study by Julian Birkinshaw at the London Business School and author of Becoming A Better Boss shows in his research that many employees are engaged in tasks to keep busy rather than focusing on priority work, and managers measure busyness levels rather than results.

Several researchers have argued that “busyness can become a manic defense (Klein, Akhtar). Typically, people who use this defensive strategy spend all of their time rushing from one task to the next, unable to tolerate even short periods of inactivity. Even their leisure time is a series of “should”and “have tos,”things to be checked off an actual or mental list. These people distract their conscious mind with either a flurry of activity or feelings of euphoria, purposefulness and the illusion of control.

Many people fear the consequences of silencing the noises that bombard the. Distraction-inducing behaviors, like constantly checking email, stimulate the brain to shoot dopamine into th bloodstream, giving us a rush than can make stopping so much harder. But if we don’t allow ourselves periods of uninterrupted, freely associative thought, personal growth, insight and creativity ae less likely to emerge (Ghiseline, Arieti, Gardner, Amabile, Sternberg, Runco).

Myth 3: Multi-tasking increases productivity

This is another workplace and lifestyle myth that is perpetuated despite evidence to the contrary. First, let’s start by defining what we mean when we use the term multitasking. It can mean performing two or more tasks simultaneously, or it can also involve switching back and forth from one thing to another. Multitasking can also involve performing a number of tasks in rapid succession.

In order to determine the impact of multitasking, psychologists asked study participants to switch tasks and then measured how much time was lost by switching. In one study conducted by Robert Rogers and Stephen Monsell, participants were slower when they had to switch tasks than when they repeated the same task. Another study conducted by Joshua Rubinstein, Jeffrey Evans and David Meyer found that participants lost significant amounts of time as they switched between multiple tasks and lost even more time as the tasks became increasingly complex.

“The neuroscience is clear: We are wired to be mono-taskers,” writes Cynthia Kubu, PhD, and Andre Machado, MD. “One study found that just 2.5 percent of people are able to multitask effectively. And when the rest of us attempt to do two complex activities simultaneously, it is simply an illusion.”

In the brain, multitasking is managed by what are known as mental executive functions. These executive functions control and manage other cognitive processes and determine how, when and in what order certain tasks are performed. According to researchers Meyer, Evans and Rubinstein, there are two stages to the executive control process. The first stage is known as “goal shifting” (deciding to do one thing instead of another) and the second is known as “role activation” (changing from the rules for the previous task to rules for the new task).

Switching between these may only add a time cost of just a few tenths of a second, but this can start to add up when people begin switching back and forth repeatedly. This might not be that big of a deal in some cases, such as when you are folding laundry and watching television at the same time. However, if you are in a situation where safety or productivity are important, such as when you are driving a car in heavy traffic, even small amounts of time can prove critical. Meyer suggests that productivity can be reduced by as much as 40 percent by the mental blocks created when people switch tasks.

Don’t try to multitask. It ruins productivity, causes mistakes, and impedes creative thought, says Earl Miller, a professor of neuroscience at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT of you are probably thinking, “but I’m good at it!” Sadly, that’s an illusion. As humans, we have a very limited capacity for simultaneous thought — we can only hold a little bit of information in the mind at any single moment.

Myth 4: Time is fixed and the same for everyone

To be most effective, you must move beyond time management to time mastery. Time managers are reliant on clocks and calendars; time masters develop an intuitive sense of timing. Time managers see time as a fixed, rigid constant; time masters view it as relative and malleable. Time masters have what John Clemens and Scott Dalrymple, call the critical skill of “temporal intelligence.”

Based on more than four years of research, “Time Mastery” includes dozens of examples of leaders whose temporal intelligence has helped them achieve business breakthroughs at organizations such as GE, 3M, Staples, and Dell. Readers will learn to develop six time-mastery behaviors, including how to: treat time as a continuous “”flow”” of peak experience; set the rhythm of their organization; look beyond the moment and encourage long-term, strategic thinking; and use time as an energizing principle that drives improvement. With intriguing examples from sports, science, history, and the performing arts, as well as business, “Time Mastery” takes a fascinating, in-depth look at a surprising new leadership skill.

According to neuro-scientific research highlighted by Inc. Magazine, how the brain perceives time passing determines whether our days feel luxuriously long, or short and harried — and it’s something that we have a certain level of control over. By paying attention and actively noticing new things, we can slow time down.

The 2011 New Yorker profile of David Eagleman,a neuroscientist who studies time perception and calls time a “rubbery thing” that changes based on mental engagement. The more detailed the memory, the longer the moment seems to last. “This explains why we think that time speeds up when we grow older,'”Eagleman said “why childhood summers seem to go on forever, while old age slips by while we’re dozing. The more familiar the world becomes, the less information your brain writes down, and the more quickly time seems to pass.”

British journalist Claudia Hammond echoed the idea that the amount of input our brain is receiving at any given moment can create a “time warp.” An Elle review of her new book, Time Warped: Unlocking the Mysteries of Time Perception, explained: “Humans seem to process the world in three-second increments (the duration of a handshake, the length of the annoying sound computers make when they start up, and the periodic rhythm of speech), and we develop a sense for how those increments sync with clock time.

Time can warp when our brain receives much more or less input than usual in a three-second span. (For example, time slows down when you are about to crash your car, but you can easily lose a whole day watching things on YouTube.)”

One study from the Journal of Consumer Psychology suggests that the more attention we pay to an event, the longer the interval of time feels. Another study from the Journal of the Association for Psychological Science had similar findings.

Myth 5: Quick decisions are better than slow decisions

How many leaders struggle with decision-making? They know it’s a key measure of their effectiveness — in fact, many of the leaders I work with say the best bosses they ever had were “decisive.”

What exactly do they mean? One dictionary says “decisive” people make decisions “quickly and effectively.” Another says “quickly and surely.” Still another says “quickly and confidently.” Notice what they have in common. Decisive people, the dictionaries say, make decisions quickly.

In their book, Decisive: How to Make Better Choices in Life and Work, brothers and academics Chip (of Stanford Graduate School of Business) and Dan Heath (of Duke) explore how to eliminate biases and improve the quality of our decisions. One of the biggest decision-making mistakes they tackle is our tendency not to waffle but to decide too quickly. Stanford’s Re:Think newsletter explains that the authors devote a considerable portion of the book to the idea of widening your options, advice that may seem at odds with the very definition of decision making.

If decision making is the process of zeroing in on the best choice, why would you widen your array of choices? The reason, [Chip] Heath explains, is our tendency to get quickly locked into one alternative. We ask ourselves, for example, whether we should fire an underperforming worker–as if to do or not to do is the only choice we have. But when you stop to think of other options–one of the authors’ many tips is to imagine that your current options are vanishing–you’ll often discover an answer that’s better than what you had been pondering.

Could you move your employee to a role he’s more suited for? Or give him a mentor to improve his performance? Heath cites research showing that people who had considered even one additional alternative did six times better than those who had considered only a single option.

The goal, in other words, isn’t to go fast and eliminate options. It’s to slow down and add them. So how do you accomplish this? The key, the authors say, is taking the time to gather information and alternatives. Using devil’s advocates, asking people who have solved similar problems, gathering relevant statistics, and soliciting the advice of friends and family members can all help.

The Heath brothers aren’t the only people warning leaders not to be seduced by quick decision making, of course. Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman wrote a whole best-selling book on the limitations of quick thinking called, appropriately, Thinking, Fast and Slow. If you haven’t picked it up yet, it’s well worth a read in full and is packed with examples of how our knee-jerk decision-making machinery can lead us astray, as well as techniques to short-circuit bias.

But for the quick-and-dirty summary, look to Harvard Business Review, which offers this article on one technique, the premortem, and another article by Kahneman himself outlining the basics of why quick decision making is often bad decision making.

Doing nothing: being is not doing

In a hypermodern society propelled by the twin engines of acceleration and excess, doing nothing is equated with waste, laziness, lack of ambition, boredom or “down” time.

But this betrays a rather instrumental grasp of human existence.

Much research — and many spiritual and philosophical systems — suggests that detaching from daily concerns and spending time in simple reflection and contemplation are essential to health, sanity and personal growth.

Similarly, to equate “doing nothing” with nonproductivity betrays a short-sighted understanding of productivity. In fact, psychological research suggests that doing nothing is essential for creativity and innovation, and a person’s seeming inactivity might actually cultivate new insights, inventions or melodies.

Carl Honore, in his book In Praise of Slowness,describes legends such as Isaac Newton grasped the law of gravity sitting under an apple tree; Archimedes discovered the law of buoyancy relaxing in his bathtub; while Albert Einstein was well-known for staring for hours into space in his office.

Walter Crosby Eelis describes in detail how the academic sabbatical is centered on the understanding that the mind needs to rest and be allowed to explore in order to germinate new ideas.

Doing nothing — or just being — is as important to human well-being as doing something.

The key is to balance the two. Take your foot off the pedal.

Since it will probably be difficult to go cold turkey from an accelerated pace of existence to doing nothing, one first step consists in decelerating. One relatively easy way to do so is to simply turn off all the technological devices that connect us to the internet — at least for a while — and assess what happens to us when we do.

Danish researchers found that students who disconnected from Facebook for just one week reported notable increases in life satisfaction and positive emotions. In another experiment, neuroscientists who went on a nature trip reported enhanced cognitive performance.

Different social movements are addressing the problem of acceleration. The Slow Food movement, for example, is a grassroots campaign that advocates a form of deceleration by rejecting fast food and factory farming.

As we race along, it seems as though we’re not taking the time to seriously examine the rationale behind our frenetic lives — and mistakenly assume that those who are very busy must be involved in important projects.

Touted by the mass media and corporate culture, this credo of busyness contradicts both how most people in our society define the good life” and the tenets of many Eastern philosophies that extol the virtue and power of stillness.

French philosopher Albert Camus put it best when he wrote, “Idleness is fatal only to the mediocre.”

In Praise of Slowing Down and “Wasting Time”

According to a 2011 study, when our attention is at rest (i.e., during bouts of idleness or laziness), the places our mind wanders to include the future (48% of the time), the present (28%) and the past (12%). This matters because, in the process, we can “literally become more creative and better at problem-solving,” researchers found. In other words, a wandering mind allows us to do three critical things:

- Plan for the future. We think about the future 14 times more often when our attention is free to roam, compared to when we focus on just one thing. So without even realizing it, we’re reflecting on long-term goals and setting intentions.

- Come up with new ideas. Try to remember the last time you came up with a creative idea or solution. Chances are it didn’t happen when you were racing to beat a deadline. Instead, you may have been taking a long shower or sitting on a bench enjoying park scenes.

- Make time to recharge. When our brains are at rest, we’re actually conserving our mental and physical energy so we can expend them on the right things. In a way, we’re also investing in our mental health.

Researchers have also shown that passive, unfocused moments are necessary for “Eureka” creative experiences to occur (Isaksen, Trefflinger, Smith, Dodds, Ward, Dietrich).

Reconceptualizing How We Structure Work

University of California, Davis professors Kimberly Elsbach and Andrew Hargadon have suggested that we find ways to balance our workday activities with a mix of “mindful” (cognitively demanding) and “mindless” (cognitively facile) activities. Giving the mind a rest from high-stakes responsibilities and strategically doing simple (but necessary) administrative or hands-on tasks give us freedom to take control of our schedules and maintain momentum with less cognitive strain.

More broadly, the philosophy of “slow work” challenges the unsustainable practice of doing everything as fast as possible and offers an alternative workplace framework for energizing people and helping people better align their personal and professional priorities. It urges us to punctuate our routines in ways that might initially appear to compromise productivity but actually enhance long-term creativity.

Stephanie Brown, author of Speed: Facing Our Addiction To Fast and Faster—And Overcoming Our Fear of Slowing Down, argues we are addicted to busyness and accept it as a norm: “There’s this widespread belief that thinking and feeling will only slow you down and get in your way but it’s the opposite.” She argues, and most psychotherapists would contend, that suppressing negative feelings only gives them more power, leading to intrusive thoughts, which can prompt people to be even busier to avoid them.

Manfred Ket De Vries, INSEAD Distinguished Professor of Leadership development and Organizational Change, writing in INSEAD Knowledge argues, “In today’s networked society we are at risk of becoming victims of interaction overload. Introspection and reflection have become lost arts as the temptation to ‘just finish this’ or ‘find out that’ is often too great to risk.”

De Vries argues that working harder is not working smarter and in fact, setting aside regular periods of “doing nothing” may be “the best thing we can do to induce states of mind that nurture our imagination and improve our mental health.”

De Vries contends that “doing nothing” has become unacceptable. People associate it with irresponsibility, and wasting valuable time. It doesn’t provide the stimulation that busyness and distraction-inducing behaviors like constantly checking emails, Facebook and texting do. The biggest danger, he says, is not so much that we lose connection with each other, but with ourselves.

De Vries, in several publications has argued the following:

- “Doing nothing and being bored can be invaluable to the creative process. In our present networked society, introspection and reflection have become lost arts. Instead, we are at risk of becoming victims of informational overload. The balance between activity and inactivity has become seriously out of sync. However, doing nothing is a great way to induce states of mind that nurture our imagination. Slacking off may be the best thing we can do for our mental health. Seemingly inactive states of mind can be an incubation period for future bursts of creativity.”

- “Keeping busy can be a very effective defense mechanism for warding off disturbing thoughts and feelings. But by resorting to manic-like behavior we suppress the truth of our feelings and concerns, consciously or unconsciously avoiding periods of uninterrupted, freely associative thoughts. Yet unconscious thought processes can generate novel ideas and solutions more effectively than a conscious focus on problem solving.”

- “I believe that our e-efforts at productivity may have a very dark side. To be able to function well psychologically and physically, we need periods of calm. Our frenetic activities in cyberspace—a world of multitasking and hyperactivity—help us to delude ourselves, however, that we are both virtuous and productive.”

- “The most effective executives are those who can both act and reflect—which means making time to do nothing. Doing nothing involves unplugging ourselves from the compulsion to keep busy, the habit of shielding ourselves from certain feelings, the tension of trying to manipulate our experience before we fully acknowledge what that experience is. Doing nothing gives us the opportunity to look at the dark side of our nature, a domain of great energy and passion. But it takes courage to go to the regions of our mind that we’re usually busy avoiding.”

- “The suggestion here is that doing nothing might turn out to be the best way to resolve complex issues. Slacking off—making a valiant effort not to be busy and letting our mind wander—might be the best thing we can do for our mental health. I realize, however, that making a case for laziness is counterintuitive. It doesn’t fitcontemporary life and from an impression management perspective looks pretty negative. But “doing nothing”—just sitting in a café, strolling in the park, lying on the beach, or even staring into space while everyone else is running busily about—may be one of the most creative things we can do.”

De Vries vigorously argues that the The time may have come for more organizations to recognize the power of doing nothing and the positive value of boredom. To be more effective, we need to allow others and ourselves regular disconnection from busyness and schedule times in our days when we are completely free to reflect and think..

Any activity that takes our mind off the problem at hand, that allows our thoughts to roam freely or helps us focus on an entirely different activity, might do the trick. Incubation time isn’t just for the specially gifted. It’s for all of us. Only by “unthinking” can we really arrive at new, creative ideas.

Incubation time can be introduced in many ways. For example, a number of companies have turned to mindfulness and meditation practices to help their employees tap into their creative potential. Companies such as 3M, Pixar, Google, and Twitter have made disconnected time, or contemplative practices, key aspects of their way of working. The objective is to increase their employees’ self-awareness, self-management and creativity. They want them to work smarter.

Modern life is built around social contact, and in that way the COVID-19 pandemic has hit us hard. Yet, it would be shortsighted to think that our entire lives 247 should revolve around social interaction in some form. None of us wants to disappoint other people, and on some level we all want approval.

Saying no is hard when we want to please but if we are going to maintain a modicum of private space we have to learn to do so. Being able to saying no is one of the most useful skills we can develop. Saying no to unimportant requests can free up time for more important things; and resisting daily distractions can give us the space we need to focus on what really matters. Saying no is not necessarily selfish and by the same token, saying yes to every request is not healthy.

When we say no to a new commitment, we’re honoring our existing obligations and ensuring that we’ll be able to devote high-quality time to them. If we are unable to say no, everyone ends up frustrated, ourselves in particular. We need to take care of our own needs before we can begin to be helpful to others. When we’re overcommitted and under too much stress, we’re more likely to feel run-down and may even get sick.

In our cyber age, where we have almost limitless selection of entertainment and distraction, it’s become easier to be in a constant state of busyness than it is to do nothing. The myriad of our activities and world of multi-tasking deludes us that we are actually being more productive. The problem is we have lost the knowledge of balancing action with reflection. And the result can be psychological burnout.

Leaders in organizations are much to blame. Work addicts are highly encouraged, supported and rewarded. Yet, study after study shows there is not a causal relationship between working hard and working smart. In fact, a workaholic environment can actually not only contributes to significant personal and mental health problems but productivity can actually decline.

We seemed to have forgotten a long history of belief and practice that doing nothing is a valuable opportunity to stimulate unconscious creative and innovating thinking. We need time to incubate our thinking. Doing nothing can be one of the best ways to deal with complex issues.

In the scientific journal Nature, author Kerri Smith reviews the brain research regarding the importance of downtime and doing nothing. In a resting “do nothing” state, the brain is not doing nothing. It is completing the unconscious tasks of integrating and process conscious experiences.

Other studies suggest that not giving yourself time to reflect impairs one’s ability to empathize with others. The more in touch we are with our feelings and inner experiences, the more accurate and compassionate we become about what others are experiencing.

“Idleness is not just a vacation, an indulgence or a vice; it is as indispensable to the brain as vitamin D is to the body, and deprived of it we suffer a mental affliction as disfiguring as rickets,” essayist Tim Kreider wrote in The New York Times. “The space and quiet that idleness provides is a necessary condition for standing back from life and seeing it whole, for making unexpected connections and waiting for the wild summer lightning strikes of inspiration—it is, paradoxically, necessary to getting any work done.”

Kate Murphy, in her article in the New York Times reviewing Timothy Wilson’s research speculates that when people are left alone they tend to dwell on what’s wrong in their lives, and until there is resolution, they ruminate and worry. Ethan Kross, director of the Emotion and Self-Control Laboratory at the University of Michigan says, “one explanation why people keep themselves so busy and would rather shock themselves is that they are trying to avoid that kind of negative thinking…[and] it doesn’t’ feel good if you’re not intrinsically good at reflecting.”

Researchers have found that resting minds are creative minds. Numerous studies have shown that people tend to develop more novel, inventive and innovative ideas if they allow their minds to wander rather than a narrow focus on one task. Some companies such as Google recognized this fact and provide professional growth courses such as “Search Inside Yourself,” and “Neural Self-Hacking,” and also mindfulness meditation where the goal is to recognize and accept inner thoughts and feelings rather than avoiding or repressing them.

Anders Ericsson, a professor of psychology at Florida State University,conducted a study in Berlin and found that the amount of time successful musicians spent practicing each day was surprisingly low—a mere 90 minutes per day. In fact, the most successful musicians not only practiced less, but also took more naps throughout the day and indulged in breaks during practice when they grew tired or stressed.

In a recent thought-provoking review of research on the default mode network, Mary Helen Immordino-Yang of the University of Southern California and her co-authors argue that when we are resting the brain is anything but idle and that, far from being purposeless or unproductive, downtime is in fact essential to mental processes that affirm our identities, develop our understanding of human behavior and instil an internal code of ethics—processes that depend on the default mode network (DMN)

Related research suggests that the default mode network is more active than is typical in and some studies have demonstrated that the mind obliquely solves tough problems while daydreaming—an experience many people have had while taking a shower. Epiphanies may seem to come out of nowhere, but they are often the product of unconscious mental activity during downtime.

There is plentiful research to show that working too much leads to life-shortening stress and disengagement at work, as pointed out in Rebecca Rosen’s article in The Atlantic. She cites Alexandra Michel of the University of Pennsylvania professor a former Goldman Sachs associate who found in her research that two well-known investment bank employees were working an average of 120 hour weeks, which led workers, Michel says, to not only “neglect family and health,” but also to work long hours even when their bosses did not ask them to.

Michel concluded that these hardworking individuals put in long hours not for “rewards, punishments, or obligation,” but rather “because they cannot conceive otherwise even when it does not make sense to do so.”

Part of the explanation for overwork can be found in North American beliefs about work—that work is an inherently noble pursuit and desirable personal trait. Yet, the widespread belief that happiness and life satisfaction can be found exclusively through hard work is more of a management motivation myth than it is a philosophical truism. Some, but not many companies believe that overwork is not a sign of dedication but a marker of inefficiency.

In my work as an executive and leadership coach, I stress the importance of developing the important habits of reflection time, energy renewal, “doing nothing,” and working less which can actually result in greater productivity and certainly a more fulfilled life.

A study published in the journal Psychological Science suggests that simply having the choice to sit back and do nothing during your day-to-day grind actually increases your commitment to a certain goal, and may even boost your likeliness to achieve that goal.

“The funny/interesting thing is that most people think that making a ‘do nothing’ option salient at the time of choice will result in people being less persistent,” study co-author Dr. Jeffrey Parker, an assistant professor of marketing at Georgia State University. The study included three separate experiments in which more than 100 men and women were put into different groups to complete a series of online cognitive tasks. Some of these groups were given the choice to complete one of two tasks or “opt out” of participating. The other groups were not given a choice to “opt out.”

All of the participants were offered a payment for doing the tasks, making the “opt out” choice unappealing. At the end of the tasks, the researchers found a major difference in the performance of people who had a choice to opt out, and those who didn’t.

In an article in the New York Times, management guru Tony Schwartz cites research that shows downtime, napping and sleep significantly contribute to performance enhancement.

Practical Slowing Down Strategies and Habits

- Practice mindfulness meditation.Mindfulness meditation research has been shown to not only be beneficial for stress reduction, but also help your brain develop a greater capacity for cognitive tasks, attention and focus. Many organizations are now incorporating meditation practices for employees into the workplace.

- Live a mindful life.Beyond the formal practice of mindful meditation, engaging in mindful life practices such as focusing being in the present; withholding judgments; not having attachment to expectations; practicing gratitude and compassion; behaving in a non-reactive manner; developing open-heartedness; being curious with “beginner’s mind;” developing self-acceptance; and developing patience.

- Protect your focus time.Block chunks of time on your work calendar for focusing on tasks that require intense concentration, and make it clear to others to not interrupt you. Doing so signals to others that you are serious about accomplishing specific goals and are therefore prioritizing the tasks needed to accomplish them.

- Seriously reduce or eliminate multitasking from your work routine. This includes the discipline of not being “on” all the time by checking your email and social media platforms.

- Block in reflection time.Rather than the always focusing on the immediate tasks of doing what is required or expected, taking a regular block of time each day or once a week to reflect without actually doing anything, on your feelings, your long range goals or vision for the future, uses a different creative part of your brain that is beneficial for satisfaction and stability.

- Eat mindfully.Eating more mindfully can be a meditative practice. Chew every bite slowly, analyze tastes like you’re a foodie, and generally savor the experience. Don’t view eating as an interruption into your activity filled life and something you need to finish quickly so you can get on with more important things.

- Do nothing when you wake up.Rather than immediately jumping out of bed to shower and rush to work, or hurriedly checking your messages on your computer or phone, taking 10 or 15 minutes to just lie there and notice your thoughts without engaging with them, helps you ease into the day with calm.

- Stop overscheduling your family life.More activities in the absence of quality slow time do not make for a better life either for you or your family. Having unscheduled, spontaneous and unplanned time for yourself and your family is critical to work-life balance.

- Learn how to say no.Saying yes can open you up to new possibilities challenges, but saying yes all the time makes you needy and can reinforce an external source for your self-esteem. Saying no can gives you a chance for me-time–an hour when you don’t have to keep any commitments or please anyone else, or a half-hour when you can just kick back and do absolutely nothing.

- Walk more and drive less.Park the car and try walking to different places. Walking helps break the conditioning that wasting time was more critical than wasting focus. Deliberately taking walks may reduce your time, but it forces you to slow down your thinking so you can focus when you need to.

- See time as a flexible flow from the past to the present to the future.This means seeing time as continuous and elastic rather than separated and broken into intervals. Learn how to set your internal time clock, which is inner directed, and separate from the external time clock. You have the capacity to slow down or speed up time when the context or situation demands it using only your mind. Understand that people and organizations have unique time rhythms. You can adapt to and influence that rhythm. This means learning how to recognize when the two are out of sync, and how to synchronize the two.

We all need to dare to make time in our daily life to do nothing— even be bored—and indulge in some quiet reflection. For busy people, that idea mayseem worthy of only a very hollow laugh. So many of us are so action-oriented, oraction-addicted, that time for reflection is no longer part of our make-up.

Each day,we are carried away by yet another project, yet another activity, and allow little or no time to stop and look at what is happening to us and the people around us. Yet our compulsive and relentless communication and our obsessive activity may be the emotional and intellectual equivalent of fast food and just as bad for our health. It may seem counterintuitive but stopping for a while and stepping off the treadmill can actually help us progress more quickly and effectively. Confucius once said, “Learning without reflection is a waste, reflection without learning is dangerous.”

There should be nothing laughable in getting away from it all and asking ourselves who we are, where we have come from and where we are going. The answers might reveal that we have been so concerned with an idea of what we ought to be that we have failed to take into account the things that make us who we really are. We may realize that if we just go forward blindly, creating more unintended consequences, in the end we may fail to achieve anything substantial. There’s a terrible price to be paid when our exterior life is not an honest reflection of our interior life—when we are out of sync with what really matters. And when we turn away from that inner exploration and look outside ourselves for answers, it becomes very hard to avoid or correct that disconnect.

Give yourself permission to be lazy.

Hardly anything saps our productivity more than an anxious mind. Now more than ever, we need idleness and the calmness that it brings.

So stop being so busy and allow your brain to do nothing. Stop obsessing over the news. Forget about the value of your time. Detach yourself from the productivity mindset.

Wait for your mind to tell you what it needs, rather than what it craves. After a certain amount of time, you’ll find that your brain has slowed. Then, go take that walk. Watch some Netflix. Listen to some music. Soak in a warm bath.

It might just be one of the most productive things you’ll do today.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book:Read my latest book: I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.