By Ray Williams

March 8, 2021

Social scientists have long known that the rich are not exactly model citizens. They evade taxes more often, flaunt traffic laws that protect pedestrians and donate less frequently to charity. In the aftermath of the Great Recession and current pandemic, there has been no shortage of reports in the popular media on their selfishness and opportunism.

One study found rich people apparently care less about the less fortunate than their middle-class counterparts.

That’s one conclusion drawn from a new study by the Chronicle of Philanthropy that found that rich people give a smaller share of their income to charity the middle-class Americans do.

While households that make at least $100,000 per year give an average 4.2 percent of their discretionary income to charity, those that make between $50,000 to $75,000 per year give an average 7.6 percent of their discretionary income to charity, according to the study.

It seems that rich people living in wealthy enclaves are the worst when it comes to thinking of the poor. In ZIP codes where more than 40 percent of taxpayers make more than $200,000 per year, residents give an average 2.8 percent of their discretionary income to charity. Many of those rich residents give no m to charity at all.

The Atlantic reports that the lowest-earning 20% of Americans donated 3.2 percent of their income to charity, while the highest-earning 20% donated only 1.3 percent. And of the 50 largest charitable gifts in 2012, for example, none went to organizations focused on social service or poverty. The big winners: elite universities and museums, where wealthy donors can have their names proudly on display to the public.

Wealthy People Not More Compassionate or Loving

People with higher incomes tend to feel prouder, more confident and less afraid than people with lower incomes, but not necessarily more compassionate or loving, according to research published by the American Psychological Association.

In a study of data from 162 countries, researchers found consistent evidence that higher income predicts whether people feel more positive “self-regard emotions,” including confidence, pride and determination. Lower income had the opposite effect, and predicted negative self-regard emotions, such as sadness, fear and shame. The research was published in the journal Emotion.

The findings were similar in both high-income countries and developing countries, said lead researcher Eddie M.W. Tong, PhD, an associate professor of psychology at the National University of Singapore.

“The effects of income on our emotional well-being should not be underestimated,” he said. “Having more money can inspire confidence and determination while earning less is associated with gloom and anxiety.”

In what they called the most comprehensive analyses to date, the researchers conducted an independent analysis and a meta-analysis of five previous studies that included a survey of more than 1.6 million people in 162 countries. The analyses also included a category of emotions people feel about others, such as love, anger or compassion. Unlike self-regard emotions, the studies didn’t find a consistent link between income level and how people feel about others.

“Having more money doesn’t necessarily make a person more compassionate and grateful, and greater wealth may not contribute to building a more caring and tolerant society,” Tong said.

The findings from the study are correlational, so the study can’t prove if higher income causes these emotions or if there is just a link between them.

Levels of income also may have long-term effects. In an analysis of a longitudinal survey including more than 4,000 participants in the United States, the researchers found that higher income predicted higher levels of self-regard emotions about 10 years after the initial survey of participants, while low income predicted greater levels of negative self-regard emotions, such as fear and shame.

“Policies aimed at raising the income of the average person and boosting the economy may contribute to emotional well-being for individuals,” Tong said. “However, it may not necessarily contribute to emotional experiences that are important for communal harmony.”

Wealthy People Have a Sense of Entitlement

Berkeley psychologists Paul Piff and Dacher Keltner ran several studies looking at whether social class (as measured by wealth, occupational prestige, and education) influences how much we care about the feelings of others

These findings build upon previous research showing how upper class individuals are worse at recognizing the emotions of others and less likely to pay attention to people they are interacting with (e.g. by checking their cell phones or doodling).

But why would wealth and status decrease our feelings of compassion for others? After all, it seems more likely that having few resources would lead to selfishness. Piff and his colleagues suspect that the answer may have something to do with how wealth and abundance give us a sense of freedom and independence from others. The less we have to rely on others, the less we may care about their feelings. This leads us towards being more self-focused.

Another reason has to do with our attitudes towards greed. Like Gordon Gekko, upper-class people may be more likely to endorse the idea that “greed is good.” Piff and his colleagues found that wealthier people are more likely to agree with statements that greed is justified, beneficial, and morally defensible. These attitudes ended up predicting participants’ likelihood of engaging in unethical behavior.

Given the growing income inequality in the United States, the relationship between wealth and compassion has important implications. Those who hold most of the power in this country, political and otherwise, tend to come from privileged backgrounds. If social class influences how much we care about others, then the most powerful among us may be the least likely to make decisions that help the needy and the poor. They may also be the most likely to engage in unethical behavior. Keltner and Piff speculated in the New York Times about how their research helps explain why Goldman Sachs and other high-powered financial corporations are breeding grounds for greedy behavior. Although greed is a universal human emotion, it may have the strongest pull over those of who already have the most.

A research paper, “Higher Social Class Predicts Increased Unethical Behaviour,” by Stéphane Côté of the University of Toronto and Paul Piff and Robb Willer of Berkeley, was published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, showing, basically, that rich people can be unethical jerks. One test found that drivers of nice cars are more likely to cut people off in traffic. Other work has shown that upper-class people are less compassionate than lower-class people, for instance toward children suffering from cancer. It’s also been shown that lack of empathy makes people more utilitarian — more likely to focus on the consequence of an act, even if the act breaks certain rules. Psychopaths are more willing to push the fat man in front of the trolley.

In the first of three studies reported in the new paper, participants answered several questions online about money worries and about their wealth growing up, for a measure of social class. Then they read the footbridge dilemma. The higher their class, the more likely they were to say pushing is okay (Even controlling for age, gender, ethnicity, religiosity, and political orientation.)

In the second study, participants were told they were playing a game with four other people online, and that they’d randomly been assigned the role of “decider.” Further, they were told that each of the five participants would receive $5, but the decider could take money from one of the other players. Each dollar taken would be multiplied by two and distributed to each of the other three players (but not the decider). So one dollar becomes six. Subjects reported their household income, how much compassion and sympathy they felt for the player who would have money taken from him, and how much money they were going to take. Income was correlated with dollars taken, and this pattern was partially accounted for by reduced empathy. The wealthier the subject, the less he cared about the victim and the more willing he was to steal from him for the group’s overall benefit.

The third study was like the second, but some subjects were asked to write about the feelings of the victim before taking his money. This time, among those who wrote about the victim, there was no class difference in dollars taken. Thinking about the victim’s feelings increased the empathy of upper-class participants to match that of the others.

Another of Keltner’s students, Jennifer Stellar, tested the correlation between social class and compassion, using physiology, not behavior, as her measure. First, Stellar asked 65 Berkeley undergraduates to fill out questionnaires describing their family education and income levels. Then she hooked up each subject to a heart-rate monitor and showed him a pair of short videos: an instructional clip about how to build a backyard deck (this was the control) and an advertisement for St. Jude’s hospital, a facility that specializes in treating children with cancer. The ad shows young kids with chemotherapy-bald heads submitting to medical tests as if they were everyday occurrences, while their devastated parents try to be brave. It is, in nontechnical terms, a tearjerker.

In post screening interviews, all the subjects said they found the St. Jude’s video moving. But compassion can also be empirically measured, because it manifests in facial expressions and a slowing of the heart rate. Looking at the data from the heart monitors, Stellar found a direct, negative correlation in biological terms between class and compassion. “Lower-class individuals showed greater heart-rate deceleration in response to the suffering of others,” Stellar wrote. The heart rates of the upper-class subjects generally did not change. When I met her, Stellar was careful, like Vohs, to stress that this upper-class numbness was not intentional. “It’s not, ‘I can see you’re suffering. I can tell. But I don’t care,’ ” she explains. “They’re just not attuned to it.”

Entitlement During the Pandemic

Athletes, politicians, and other wealthy or well-connected people have managed to get special treatment throughout the pandemic, including preferential access to testing and unapproved therapies. Early access to coronavirus vaccines is likely to be no different, medical experts and ethicists told STAT. It could happen in any number of ways, they said: fudging the definition of “essential workers” or “high-risk” conditions, lobbying by influential industries, physicians caving to pressure to keep their patients happy, and even through outright bribery or theft.

Wealthy People Have Fewer Social Connections and Interactions

Rich Americans aren’t only getting richer. They’re becoming more isolated from the rest of America, too.

An analysis of survey data from more than 100,000 Americans finds that the rich spend significantly less time socializing than low-income Americans. On average, they spend 6.4 fewer evenings per year in social situations.

Rich Americans spend less time socializing with their family and neighbors — although they do spend more time socializing with friends.

The study is part of a growing body of research that suggests a yawning gap between what it means to be rich and poor in the United States.

For years, American society has become both more affluent and more stratified. Now this empirical evidence shows that for the rich it is becoming more exclusive, reflecting the phenomenon of the “velvet rope economy”and increasing economic segregation.

A research study’s co-authors — Emory University’s Emily Bianchi and the University of Minnesota’s Kathleen Vohs — analyzed results from the General Social Survey and American Time Use Survey. The studies controlled for a variety of variables in order to generate estimations of the specific impact household income has on people’s social connections. For example, the study controlled for differences in gender, race, marital status, geographic location, living arrangements, city size, and more.

In addition to looking at evenings spent socializing, the authors also examined how a typical day plays out for Americans at different income levels. They found that people with higher incomes spent an estimated 10 minutes more alone in a day, 22 minutes more with friends, and 26 minutes fewer with family than people with lower incomes.

To estimate the minutes per day, the authors counted low income as earning $12,340 and high income as $105,086. For their work on nights socializing in a year, they used $5,427 for low and $131,203 for high.

The paper reflects psychological findings about the social behavior of people with access to different levels of money, and demonstrates how they play out in the real world. For example, previous studies have shown wealthier people to be less interested in social interactions and less compassionate than people with lower incomes. These characteristics, the authors of the paper theorize, manifest themselves in people’s social tendencies.

A social network can be more crucial to the less affluent — whereas in the gig economy, richer Americans can pay for the work that friends and families used to provide.

Relatives and neighbors are more likely than friends to provide financial help, child care needs, or home repairs, which “are likely to be crucial for managing existing and impending challenges.”

As an example, Bianchi mentioned home alarm systems. Before the technology became cheap enough for millions of Americans to afford them, it was more common to have neighbors look after your house when you left town.

Not anymore. As Bianchi points out, “That’s something you can pay for and never interact with your neighbor about that. But, again, only on certain economic levels.”

An Uber ride can replace a friend or family’s car for getting to the airport — and instead of borrowing a cup of sugar from a neighbor, TaskRabbit can now procure that same service at the tap of a screen.

“Now we can kind of, through money, pay for things that we used to rely on other people for,” Bianchi said. “As we become more affluent as a nation — as we have, and certainly not equally by any stretch — we do tend to pay for some of these things that we used to give and receive support on.”

Unlike friends, family and neighbors are driven less by choice and more by biology and geography. Friendships are based more on shared interests and values.

People in wealthier households relying less on family and neighbors for help in times of need may point to why more of their free time is spent with their chosen social circles. These relationships with friends, Bianchi said, could be more “satisfying.”

Rising affluence, Bianchi suggested, has pushed forward “individualization” — an idea that political scientist Robert Putnam wrote about in his seminal work Bowling Alone, which began as a 1995 essay and turned into a book in 2000.

Putnam argues there that the individualization of leisure time is in part responsible for a decline in civic participation.

“I’ve always been struck by the idea that we’ve become wealthier as a country and by many metrics less happy, less involved in our communities, and certainly interacting less,” she said. “That’s been a puzzle to many scholars and something that’s always captured my attention and interest. I see this as a small piece of understanding that.”

This increasing isolation is shown a number of ways. For instance, Americans are talking less and with fewer people about “important matters.” From 1985 to 2004, the percentage of Americans who said they had no one with whom to talk about “important matters” rose from 10 percent to 24.6 percent.

Wealthy People Tend to Have Less Wisdom

The research, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, suggests that people in higher social classes have a lesser tendency toward “wise reasoning” than those in lower ranks, which could be a deal breaker in a relationship.

So what exactly is wise reasoning? Igor Grossmann, the research’s co-author and an associate professor of psychology at the University of Waterloo, says wise reasoning is “more about how to manage knowledge and how to figure out a solution.” It entails open-mindedness, intellectual humility, flexibility and empathy, Grossman says, adding that ultimately, “it’s a collection of strategies that help you deal with uncertain situations in contrast to situations that are well-defined.”

Across two in-depth studies (one of which assessed participants’ views on a Dear Abby letter), Grossman and his team concluded that upper-class folks are “associated with a lower propensity of reasoning wisely in interpersonal situations.” In other words, rich people are less likely than poorer people to exhibit flexibility, empathy and all the other traits that make up wise reason when it comes to relationship.

“Although personality traits and challenges cross all socioeconomic barriers, I do see lower levels of ‘wise reasoning style’ in the upper-class and super wealthy population,” says Dr. Fran Walfish, a psychotherapist who specializes in relationships. “The reasons for this can be attributed to a particular type of narcissism in the stratospherically rich who care more about achievements, status and how they are viewed by others rather than relationships and family. Often, these folks lack accountability and self-examination skills, which is why they consistently blame others. Privilege has endowed them with a sense of entitlement. So, interpersonally these people can be rigid, [which] in psychology is thought of as pathology; flexibility is healthy.”

Professional matchmaker Susan Trombetti asserts that she doesn’t need a study to show her that “rich people are less reasonable in relationships.” She sees it all the time. “Rich people reason that they can have the world at their fingertips and whatever they want, but relationships are intangible and not easily measured,” says Trombetti. “Moreover, the richer you are, the more you are surrounded by ‘yes’ people dependent on you financially and less likely to tell you no, or that you have irrational behavior.”

People with less money may have plenty of friends and family offering advice, but that’s quite different from having people cheering you on because of their monetary interest in you. It’s easy to imagine how the latter could cloud your judgment and cause communication problems at home, she says.

Are There Psychological Differences?

The author F. Scott Fitzgerald is credited with saying: “The rich are different from you and me.” And Ernest Hemingway is supposed to have responded: “Yes, they have more money.” In fact, the actual words Fitzgerald used in his short story “The Rich Boy” (1926) are: “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft, where we are hard, cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand.”

People have always suspected that the rich are somehow ‘different,’ not only in terms of what they possess, but in their personalities. However, there are not many scientific studies that can either confirm or refute this thesis — neither in the United States, nor in Europe. Now, a team of six German economists and psychologists has conducted a large-scale study: They interviewed 130 wealthy individuals and used the results to derive a psychological profile, which they compared with the population as a whole.

Big Five Test

Of the various models developed by psychological researchers to describe personality types, it is the Big Five model that has largely come to dominate over the past few decades. This latest wealth study used a condensed version of the Big Five test to distinguish between five core personality traits:

- Conscientious: Describes people who are thorough, meticulous, diligent, efficient, well organized, punctual, ambitious and persevering.

- Neuroticism: Individuals with a high degree of Neuroticism tend to be nervous and frequently worry about everything and anything that could possibly go wrong. They tend to react impulsively and, overall, are not particularly psychologically stable.

- Agreeableness: Individuals with high levels of Agreeableness have a pronounced desire for harmony; they have a tendency to back down too quickly and are frequently too trusting.

- Extraversion:Individuals with high Extraversion are talkative, determined, enterprising, energetic, and courageous.

- Openness to Experience: Individuals with high Openness to Experience are imaginative, creative, and curious.

When researchers compared the personality traits of the general population with those of the researchers’ wealthy interviewees, the following patterns emerge:

- The rich are less neurotic.

- The rich are especially extraverted.

- The rich are more open to new experiences.

- The rich are less agreeable, which means they less likely to shy away from conflicts.

In addition to the Big Five test, the researchers also investigated two other personality traits: narcissism and internal locus of control. Their findings:

- The rich are more narcissistic.

- The rich exhibit a stronger internal locus of control. This means that they are more likely to agree with statements such as “I determine how my life turns out” than they are with statements like “What you achieve in life is mainly a question of luck or fate.”

One of the key findings of the research was that the superrich are frequently nonconformists. They enjoy swimming against the prevailing current and have no problem contradicting prevailing opinion.

Another result: the superrich are more likely than others to make decisions based on gut feeling. They tend to rely more on intuition than on detailed analysis.

The Wealthy and Educational Access Privilege

The college admissions scandal showed the length some parents will go to in order to get their children into the best schools. That Ivy League education and the networking it provides could be worth its weight in gold, especially when climbing the ladder in Corporate America.

In the course of her career and research into workplace behavior, Nicole Jones Young has noticed that some managers recognize the work of the loudest, most confident and, sometimes, the most well-heeled person in the room. That includes people who are well-known to have gone to a good school and, well, come from a wealthy background.

Most people have had at least one colleague with a sense of privilege who likes to speak first, she says, and that can often drown out other voices in the room. “This behavior may make it difficult for those of lower social classes to successfully interject and navigate the higher ranks within an organization,” Jones Young says.

High Profile People Charged with Fraudulent Entrance Exam Scam

The Wealthy Are Critical of the Poor

Behaviors indulged in the rich are not just condemned in the poor, but used as a justification to punish them, denying them access to resources that keep them alive, such as healthcare and food assistance. Discussion of poverty has become almost impossible without moral outrage directed at lazy “welfare queens”, “crackheads” and other drug addicts, and the “promiscuous poor” (a phrase that has cropped up again and again in discussions of public benefits over more than a century).

These disparate perceptions aren’t just evidence of hypocrisy; they are literally a matter of life and death. In the US, the widespread belief that the poor are simply lazyhas led many states to impose work requirements on aid recipients –even those who have been medically classified as disabled. Limiting aid programs in this way has been shown to shorten recipients’ lives: rather than the intended consequence of pushing recipients into paid employment, the restrictions have simply left them without access to medical care or a sufficient food supply. Thus, in one of the richest counties in America, a boy living in poverty died of a toothache; there were no protests, and nothing changed.

Meanwhile, former President Trump started his days at 11am– the rest of the morning is termed “executive time” — and is known for his frequent holidays. “Nice work if you can get it,”quipped an opinion piece in the Washington Post.

We don’t hear much about laziness, drug addiction or promiscuity among the wealthiest members of society because most billionaires are not public figures and go to great lengths to seek privacy. Thus the motto of one London-based wealth management firm: “I want to be invisible.” This company, like many other service providers to the ultra-rich, specializes in preserving secrecy for clients. Most wealthy people not only have wealth managers but often dedicated staff members who killed negative stories about them in the media and kept their names off the Forbes “rich list”.

Many even present themselves as homeless — for tax purposes — despite owning multiple residences. For the ultra-rich, having no fixed residence provides major legal and financial advantages; this is exemplified by the case of the wealthy businessman who acquired eight different nationalities in order to avoid taxes on his fortune, and by the UK native who was interviewed in his Dubai apartment building who said: “I am not tax resident anywhere. The tax man says ‘show me a utility bill’, and the only utility bill I can present is for the house I own in Thailand, and it’s in a language that the European authorities aren’t familiar with. With all the mobility going on in the world, international marriages, governments can’t keep up with people.”

Meanwhile, the poor can end up being “resident nowhere” because no one will allow them to stay in one place for very long; as the sociologist Cristobal Young has shown, the majority of migrants are poor people. In addition, the poor are routinely evicted from housing on the slightest pretext, frequently driving them into homeless shelters — which are in turn forced to move when local homeowners engage in nimby (not in my back yard) protests. Even the design of public spaces is increasingly organized to deny the poor a place to alight, however temporarily.

It is as if the right to move around, to take up space, and to direct your own life as you see fit have become luxury goods, available to those who can pay instead of being human rights. For the rich, deviance from social norms is nearly consequence-free, to the point where outright criminality is tolerated: witness the collective shrug that greeted revelations of massive intergenerational tax fraud in the Trump family.

For the poor, however, even the most minor deviance from others’ expectations — like buying ice cream or soft drinks with food stamps — results in stigmatization, limits on their autonomy, and deprivation of basic human needs. This makes life far more nasty, brutish and short for those on the lowest rungs of the socio-economic ladder, creating a chasm of more than 20 years in life expectancy between rich and poor. This appears to some as a fully justified consequence of “personal responsibility” — the poor deserve to die because of their moral failings.

So while the behavior of the ultra-rich gets an ever-widening scope of social leeway, the lives of the poor are foreshortened in every sense. Once upon a time, they were urged to eat cake; now the cake earns them a public scolding.

Wealthy People Are Often Overconfident and Incompetent

Wealthy people don’t always attain their wealth and success as a result of their competence, according to several research studies. It often is a result of connections and inheritance.

Individuals with relatively high social class are more overconfident and appear more competent to others. This helps them attain higher-earning jobs.

Jones Young, an assistant professor of organizational behavior at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa., is fascinated by how a person’s socio-economic background translates to how they are perceived at work. Often times, she says, they are perceived favorably. She is amazed at how some people act like they’re destined for the corner office.

Not everyone has the innate ability to eye an opportunity with that kind of confidence or, some might say, entitlement. That ambition and confidence is likely instilled in people at a young age. Jones Young says, in her experience, they often happen to be from privileged backgrounds, and that can create a structural and cultural imbalance in the workplace.

Former President Trump is known for his remarkable self-confidence and ability to speak off-script in front of a crowd. He’s also been asked about his own presidential ambitions since the 1980s, even though he had no political experience. He was regarded by interviewers as someone who would naturally aspire to the highest office in the land.

Trump, who was born into a wealthy real-estate family, has been criticized for his rudimentary and sometimes off-color language, especially his repeated use of the same words (“tremendous”). Indeed, the president himself has said he doesn’t have time to read books, but he also says that he acts on instinct.

Well-connected individuals who feel like they were born to rule the world or, at the very least, leapfrog over Kevin in accounting, make appearances in politics, academia, and cubicles and boardrooms across the land, Jones Young says. But they create a conundrum for everyone else: “How do managers or those in positions of power acknowledge these differences and create an environment where all employees have an opportunity to showcase their talents and perspectives?”

Pia Dietz and Eric Knowles studied how social class differences influence how people process information. They confirm poorer people are more likely to notice, engage with, pay attention to and empathize with other humans, compared to the rich. How relevant others are to our goals and motivation is what drives our interaction with others. With wealth and privilege comes independence. The poor on the other hand view others as potentially rewarding, threat ..

Privilege can create a sense of entitlement The rich worry more about how other view them, and are likely to consistently blame others for things going wrong. One of the reasons for poor quality personal, family and romantic relationships among the rich as compared to the poor is the former’s inability to apply themselves with flexibility, empathy and open mindedness when faced with uncertainties in personal relationships. The poor seem more willing to compromise or change their positions.

Wealthy People and Inequality

The wealthiest American households are keeping a tight grip on their purse strings even as their lower-income counterparts are spending a lot more freely when they emerge from weeks of lockdown. That decline in spending by the wealthy could limit the whole country’s economic recovery.

Researchers based at Harvard have been tracking spending patterns using credit card data. They found that people at the bottom of the income ladder are now spending nearly as much as they did before the coronavirus pandemic.

In a windowless room on the University of California, Berkeley, campus, two undergrads are playing a Monopoly game that one of them has no chance of winning. A team of psychologists has rigged it so that skill, brains, savvy, and luck — those ingredients that ineffably combine to create success in games as in life — have been made immaterial. Here, the only thing that matters is money.

One of the players, a brown-haired guy in a striped T-shirt, has been made “rich.” He got $2,000 from the Monopoly bank at the start of the game and receives $200 each time he passes Go. The second player, a chubby young man in glasses, is comparatively impoverished. He was given $1,000 at the start and collects $100 for passing Go. T-Shirt can roll two dice, but Glasses can only roll one, limiting how fast he can advance. The students play for fifteen minutes under the watchful eye of two video cameras, while down the hall in another windowless room, the researchers huddle around a computer screen, later recording in a giant spreadsheet the subjects’ every facial twitch and hand gesture.

T-Shirt isn’t just winning; he’s crushing Glasses. Initially, he reacted to the inequality between him and his opponent with a series of smirks, an acknowledgment, perhaps, of the inherent awkwardness of the situation. “Hey,” his expression seemed to say, “this is weird and unfair, but whatever.” Soon, though, as he whizzes around the board, purchasing properties and collecting rent, whatever discomfort he feels seems to dissipate. He’s a skinny kid, but he balloons in size, spreading his limbs toward the far ends of the table. He smacks his playing piece (in the experiment, the wealthy player gets the Rolls-Royce) as he makes the circuit — smack, smack, smack — ending his turns with a board-shuddering bang! Four minutes in, he picks up Glasses’s piece, the little elf shoe, and moves it for him. As the game nears its finish, T-Shirt moves his Rolls faster. The taunting is over now: He’s all efficiency. He refuses to meet Glasses’s gaze. His expression is stone cold as he takes the loser’s cash.

By making real people temporarily very affluent, without regard to their actual economic circumstances and within the controlled environment of a psych lab, the Berkeley researchers aim to demonstrate the potency of that one variable. “Putting someone in a role where they’re more privileged and have more power in a game makes them behave like people who actually do have more power, more money, and more status,” says Paul Piff, the psychologist who designed the experiment. The Monopoly results, based on a year of watching inequitable games between pairs like Glasses and T-Shirt, have not yet been released. But Piff believes that they will support and amplify his previous provocative research.

The economic data are well known: The top 20 percent of Americans own about 87 percent of the wealth; the bottom 80 percent splits the rest. Social mobility, never as attainable as imagined, is stagnant. Forty percent of Americans inhabit the same social class as their grandparents, making the United States less socially mobile than Japan or France.

Political divisions mirror the economic chasm. The solution to America’s $15 trillion debt is either “cut spending” or “raise taxes,” a polarity of world views that has led social psychologists like Jonathan Haidt to seek out the roots of those moral prejudices. When Mitt Romney, one of the richest men ever to run for president, fails to convincingly relish his “cheesy grits,” it is taken by critics as evidence that he is too out of touch to steward the economy to all citizens’ benefit — just as the fortune he amassed in private equity is proof to his supporters of his acumen as a leader of men.

Americans across the board can have a high tolerance for inequality if they believe it is meritocratic. The research by Piff and his colleagues points to a different possible explanation for the income gap: that it may be at least in part psychologically destined. This in turn raises the ancient conundrum of chicken and egg. If getting or having money can make you hard-hearted, do you also have to be hard-hearted to become well-off in the first place? The bulk of the new research points decisively in the direction of the former, says Kraus, who now works at the University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign. “Just the idea of holding money can make people selfish.

The biggest predictor of personal prosperity is your parents’ income level, and only 16 percent of people in the lowest income bracket move to the middle or above in ten years, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

It’s Just Business for the Wealthy

- Byram Karasu, a psychiatrist at Albert Einstein/Montefiore Medical Center who treats wealthy clients, believes all very successful people share certain fundamental character traits. They have above-average intelligence, street smarts, and a high tolerance for anxiety. “They are sexual and aggressive,” he says. “They are also competitive with anyone and have no fear of confrontations; in fact, they thrive on them. And in contrast to their image, they are not extroverted. They become charmingly engaging when needed, but in their private world, they are private people.” They are, in the parlance, all business.

Earlier this year, researchers led by Timothy Judge at Notre Dame went some way toward proving Karasu’s observation when they published a study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychologytitled “Do Nice Guys — And Gals — Really Finish Last? The Joint Effects of Sex and Agreeableness on Income.” The paper explored, in part, the financial penalties that women suffer in the workplace for being perceived as pushovers. But it also found a strong correlation, especially dramatic in men, between disagreeableness and income.

Subjects were asked to assess whether they had a forgiving nature or found fault with others, whether they were trusting, cold, considerate, or cooperative. Then they were given an agreeableness score. Men with the lowest agreeableness earned $42,113 in a given year; those with the highest agreeableness earned $31,259. Disagreeableness was also correlated to job responsibility and recommendations for the management track. This seeming correlation between money and insensitivity perpetuates itself, says Kathleen Vohs, a professor at the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota. “You’re reminded of money, and you act like a jerk. People don’t like you, and you’re reminded of money more.”

In her lab at the University of Minnesota, Vohs does experiments indicating that merely thinking about money can decrease empathy. Vohs is a 38-year-old psychologist who was inspired to study the effects of money on social behavior nine years ago, when she left a junior faculty position where she was making $32,000 a year, and started working at a Canadian business school, where she earned five times that much. Suddenly she was no longer asking her friends for rides to the airport. She hired a personal shopper. “I was becoming more independent and less interdependent,” she says. This led her to the next thought: “We need to understand at a theoretical level what happens to people’s minds in the context of wealth.”

In experiments she published in the journal Science in 2006, Vohs “primed” her subjects to think about money, which is to say she planted the idea of money in their minds without their knowledge before observing their social interactions compared with a control group. In one case, she asked participants to wait alone in a room at a big table, which happened to be strewn with gold, green, and burnt-orange Monopoly bills. After ten minutes, she’d get the subject, take him to a different room, and ask him to fill out piles of questionnaires seeking detailed psychological information. The point was to muddle the subject’s mind: He knew he was participating in an experiment but had no idea what he was being tested for.

Vohs got her result only after the subject believed the session was over. Heading for the door, he would bump into a person whose arms were piled precariously high with books and office supplies. That person (who worked for Vohs) would drop 27 tiny yellow pencils, like those you get at a mini-golf course. Every subject in the study bent down to pick up the mess. But the money-primed subjects picked up 15 percent fewer pencils than the control group. In a conversation in her office in May, Vohs stressed that money-priming did not make her subjects malicious — just disinterested. “It’s not a bad analogy to think of them as a little autistic,” she said. “I don’t think they mean any harm, but picking up pencils just isn’t their problem.”

Over and over, Vohs has found that money can make people antisocial. She primes subjects by seating them near a screen-saver showing currency floating like fish in a tank or asking them to descramble sentences, some of which include words like bill, check,or cash.Then she tests their sensitivity to other people. In her Science article, Vohs showed that money-primed subjects gave less time to a colleague in need of assistance and less money to a hypothetical charity. When asked to pull up a chair so a stranger might join a meeting, money-primed subjects placed the chair at a greater distance from themselves than those in a control group.

When asked how they’d prefer to spend their leisure time, money-primed people chose a personal cooking lesson over a catered group dinner. Given a choice between working collaboratively or alone, they opted to go solo. Vohs even found that money-primed people described feeling less emotional and physical pain: They can keep their hand under burning-hot water longer and feel less emotional distress when excluded from a ball-tossing game. “Money,” says Vohs, “brings you into functionality mode. When that gets applied to other people, things get mucked up. You can get things done, but it does come at the expense of people’s feelings or caring about them as individuals.”

Public-health research has long shown that poverty can have devastating effects on the brain. At 3 years old, poor kids have vocabularies that are three times smaller than their better-off peers. Their memories do not work as well. In poor children, executive function is not as developed as it is in more affluent children, which means they have a harder time sorting and organizing information, planning ahead, and coping in the event of changed circumstances.

Research by Robert Knight at Berkeley has shown that kids raised in a poor neighborhood are more likely to have frontal lobes — the area in the brain that enables attention and focus — that appear damaged. A psychologist at Oregon’s Willamette University has discovered that when very young children are given headphones that play two different stories simultaneously, one in each ear, and are told to reiterate the story heard in the right ear, affluent and poor children perform equally well. But EEGs taken of the poor kids show that they have a harder time filtering out the extraneous stimulus.

The aforementioned research seems to show that getting money and having money makes people selfish and antisocial. But it also appears to be true that selfish, antisocial people are the ones that ascend. And that is, in part, because rich or striving people tend to pass on their values and priorities to their children, as all parents do. Members of the lower and upper classes usually date and marry within their own ranks and “live in neighborhoods and attend schools and work with individuals who share similar levels of educational training and income,” write Kraus and his co-authors in their article.And so the values of each group become both more and more clearly entrenched and incomprehensible to the other.

“Parents in working-class contexts are relatively more likely to stress to their children that ‘It’s not just about you’ and to emphasize that although it is important to be strong and to stand up for oneself, it is also essential to be aware of the needs of others and to adhere to socially accepted rules and standards for behavior,” wrote a team led by Nicole Stephens, with Stanford University psychologist Hazel Markus, in 2007 in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.Parents with higher incomes “more often tell their children that ‘It’s your world’ and emphasize the value of promoting oneself and developing one’s own interests.” The cries of “Go get ’em!” you hear in the playgrounds and on the baseball diamonds of America’s best neighborhoods reflect not just concern for children’s self-esteem but a worldview that emphasizes looking out for #1.

This is Markus’s main research interest: the mind-sets of class. She and her colleagues have found, broadly speaking, that the affluent value individuality — uniqueness, differentiation, achievement — whereas people lower down on the ladder tend to stress homogeneity, harmonious interpersonal relationships, and group affiliation. In 2005, Markus co-authored a paper that showed those with only a high-school education like country music for its message of group coherence, while those with college educations like indie music because it emphasizes personal uniqueness.

In her 2007 paper, Stephens found this same variance in self-image by testing people’s preferences in ballpoint pens. She divided her subjects into two groups of lower and higher incomes and showed each subject five pens and asked him to choose one. The pens were identical and were widely considered to be good, even desirable. The only difference among them was their color. Three pens in the handful would be one color (say, green); two would be another (orange). In the test, lower-class people overwhelmingly chose the green pens, whereas higher-class people picked the less common color. Lower-class people wanted to be the same as their peers, whereas better-off subjects showed, Stephens wrote, “a preference for uniqueness and individuation.”

In another experiment, Stephens presented firefighters and MBA students with the following hypothetical situation: “You just bought a new car, and then you find that your friend has purchased the exact same car. How do you feel?” The firefighters were overwhelmingly pleased and said things like, “Fantastic. He gets a great car.” The MBA students were negative or ambivalent. “I would feel slightly irritated,” one said. “It spoils my differentiation,” said another. Madison Avenue discovered and manipulated this bifurcation in the American self-image long ago: When it sells trucks, the ads might show a parking lot full, pulled up at a multigenerational picnic, with slogans like “Take Family Time Further.” When it sells sports cars, the commercials show a car zooming down the highway alone. The slogan for the BMW M3 even nods in the direction of Piff’s discovery about the drivers of high-end cars and traffic rules: “Street Legal. Pretty Much.”

The American Dream is really two dreams. There’s the Horatio Alger myth, in which a person with grit, ingenuity, and hard work succeeds and prospers. And there’s the firehouse dinner, the Fourth of July picnic, the common green, in which everyone gives a little so the group can get a lot. Markus’s work seems to suggest the emergence of a dream apartheid, wherein the upper class continues to chase a vision of personal success and everyone else lingers at a potluck complaining that the system is broken.

Research shows that the rich tend to blame individuals for their own failure and likewise credit themselves for their own success, whereas those in the lower classes find explanations for inequality in circumstances and events outside their control.) But the truth is much more nuanced. Every American, rich and poor, bounces back and forth between these two ideals of self, calibrating ambitions and adjusting behaviors accordingly. Nearly half of Americans between 18 and 29 believe that it’s “likely” they’ll get rich, according to Gallup — in spite of all evidence to the contrary.

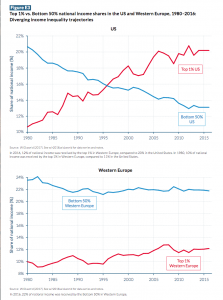

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, OECD and numerous other studies economic inequality is increasing in America, not getting better. In 2018, the top 20% of the population earned 52% of all U.S. income. Their average household income was $233,895. The richest of the rich, the top 5%, earned 23% of all income. Their average household income was $416,520.

Among high-income countries, for example, the US has the highest level of wealth inequality, the second highest level of income inequality, after taxes and government transfers, and one of the lowest levels of intergenerational mobility. An individual’s future is largely determined by their parents’ income. In 2020 alone, children will inherit about $764 billion and pay an average of just 2.1% on this income. By contrast for working people, the average tax rate is 15.8%, seven times more. These disparities are further skewed by race, and the racial wealth gap is even larger than it was in 1968, at the peak of the struggle for civil rights.

The Pew Foundation study, reported in the New York Times , concluded, “The chance that children of the poor or middle class will climb up the income ladder, has not changed significantly over the last three decades.” The Economist’sspecial report, Inequality in America,concluded, “The fruits of productivity gains have been skewed towards the highest earners and towards companies whose profits have reached record levels as a share of GDP.”

Among America’s most cherished core values is the belief that the United States is a “land of opportunity” and that we uniquely offer to citizens the potential for rising from “rags to riches” provided that citizens have the necessary ability and work hard. This is a myth. Income and wealth disparity in the United States (as measured by the Gini index of equality/inequality, and in other ways) is much higher in the United States than in any other large First World democracy. So is hereditary socioeconomic immobility, that is, the probability that a son’s relative income will just mirror his father’s relative income, and that sons of poor fathers will not become wealthy.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest books available on Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

Toxic Bosses: Practical Wisdom for Developing Wise, Moral and Ethical Leaders,

and,