The world of work in the year 2030 will be radically different than it is today. Those changes will be driven by Artificial Intelligence, automation, changing demographics and globalization.

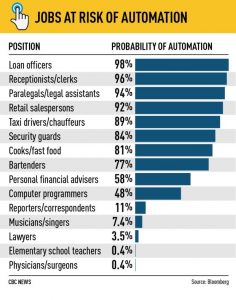

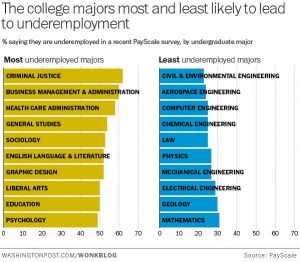

A documentary film “Humans Need Not Apply,” shows that with more tasks being done by machines, a full 45% of the current workforce can be replaced by technology that is available today. From burger bots that can make a hamburger every 10 seconds to machines that perform scientific experiments and write their own code, automated devices are finding their way into virtually every area of human endeavor. No matter what degree a student pursues today, it’s ability to provide employment to its holder cannot no longer be guaranteed.

A number of recent reports have forecasted the work world in the next two decades and present some important insights. Here’s a few to consider:

- With the aid of technology, assembly workers will wear devices that gauge their concentration, work rate, moods and physical energy levels;

- The higher education system as it is now structured will disappear or be transformed because of unsustainable costs and limited job opportunities for graduates;

- Managing complexity and ambiguity will have the single biggest impact on the way we work;

- Social responsibility will dominate the corporate agenda with prime concerns about the environment and peoples’ well being;

- Companies will break down into collaboration networks of smaller organizations;

- Work in one profession or job for an extended period of time will disappear;

- Leadership teams will replace single leaders, with their prime focus on developing positive and inclusive corporate cultures;

- The Internet of Things will shape our economy and the way we work;

- The social contract will be revised with an emphasis on ethical values and work-life balance;

- Work will be restructured on the basis of flexibility, employee autonomy and career challenges/opportunities in return for short-term or contractual employment;

- Workers will increasingly see themselves as members of a particular skill (e.g.: guild) or professional network rather than as an employee of a particular company;

- Workers will be rewarded based on their expertise and results rather than position and length of service, and therefore will have an increasing personal stake in the success of work;

- Learning and training will become flexible, personalized and collaborative.

Eighty-five per cent of jobs in 2030 have not yet been invented, according to forecasts by Dell Technologies and Institute for the Future. Experts predict some of these roles will be in the drone sector, where new jobs will range from coding and robotics to drone insurance and racing.

“Having tens of thousands of drones swarming over most metro areas on a daily basis may seem annoying at first, but the combination of new businesses, jobs, information, data analysis, new career paths, and revenue streams will quickly turn most naysayers into strong industry advocates,” Thomas Frey of DaVinci Institute said.

Bernard Salt, managing director of The Demographics Group, said workers of the future must perfect the art of forming new relationships. “If you are in the same job for 40 years you don’t have to make new relationships (but) if you are changing every two years, you have to be comfortable introducing yourself and being sociable,” he said. “We need a word that means to fearlessly fit in, infiltrate and operate effortlessly in a new situation.”

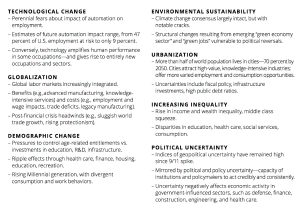

As much as one-third of the United States workforce could be out of a job by 2030 thanks to automation, according to new research from McKinsey. The consulting firm now estimates that between 400 million and 800 million individuals globally could be displaced by automation and need to find new work. McKinsey notes that governments will have to develop and provide extensive job retraining to help displaced workers as well as providing more generous income supplements. “Beyond retraining, a range of policies can help, including unemployment insurance, public assistance in finding work, and portable benefits that follow workers between jobs” as well as “[p]ossible solutions to supplement incomes, such as more comprehensive minimum wage policies, universal basic income, or wage gains tied to productivity,” the researchers wrote.

The research cited the U.S. High School Movement at the turn of the last century and the GI Bill as key examples of how developed countries can cope with the disruptive effects of a transforming economy. “In many decades hence, the value of this labor may be diminished if we reach a state in which machines can do a large share of the work,” concluded the report. “For workers around the world, policy makers, and business leaders — and not just social scientists who specialize in socio-economic paradigms — that should give pause for thought, and be a spur for action.”

“Even if there is enough work to ensure full employment by 2030, major transitions lie ahead that could match or even exceed the scale of historical shifts out of agriculture and manufacturing,” according to McKinsey Global. “Even as it causes declines in some occupations, automation will change many more – 60 percent of occupations have at least 30 percent of constituent work activities that could be automated.” Professions most susceptible to automation include physical ones in “predictable environments,” including operating machinery and preparing fast food, according to the research. Alternatively, automation will have a more muted effect on jobs that involve expertise, managing people, and that require frequent social interactions. “Unpredictable” jobs such as gardeners, plumbers, or providers of child and elder care are also less likely to see automation over the next decade, as they remain challenging to automate and don’t usually earn high wages, according to McKinsey.

This selective effect on the workforce has many worried that income inequality could continue to worsen in the United States.“Income polarization could continue in the United States and other advanced economies,” noted the research. “If reemployment is slow, frictional unemployment will likely rise in the short-term and wages could face downward pressure.”

To be sure, McKinsey isn’t the only group studying the effects of artificial intelligence on wages and economic growth.

A recent working paper penned by economists from Northwestern, Stanford and the College de France explored what would happen to economic growth if artificial intelligence starts generating original thought. A rapid uptick in the rate of innovation – and in new ideas – has led some to speculate about economic hypergrowth and ever-increasing GDP gains.

But to help transition to a future with increased automation, businesses and policymakers will “need to act” to keep people employed, suggests the McKinsey research.

Now a new report by the British innovation foundation Nesta and University of Oxford future-gazers from the Oxford Martin School tries to establish how those changes will affect skill requirements by 2030. First, the team behind the research identified occupations that look set to be automated away (such as shelf fillers, van drivers, and administrators) and those that are likely to grow in the face of technology’s encroachment (including teachers, biotech researchers, and nurses).

Then, they looked at the skills that were most common among the occupations that had the greatest prospect of growing in the future, to work out which would be most useful when the robots come. From the report, here are the top five desirable future work skills:

-

- Judgment and decision making: Considering the relative costs and benefits of potential actions to choose the most appropriate one.

- Fluency of ideas: The ability to come up with a number of ideas about a topic (the number of ideas is important, not their quality, correctness, or creativity).

- Active learning: Learning strategies—selecting and using training/instructional methods and procedures appropriate for the situation when learning or teaching new things.

- Learning strategies: Understanding the implications of new information for both current and future problem-solving and decision-making.

- Originality: The ability to come up with unusual or clever ideas about a given topic or situation, or to develop creative ways to solve a problem.

That all suggests that things like creativity, adaptability, and judgment will be more important than, say, subject-specific knowledge or the ability to use a nail gun. It’s hard to argue with that: the former skills all represent abilities that are a long way from appearing in any machine, while the latter can easily be replaced by simple AIs and robots.

The report actually goes a step further, to imagine how some of those skills may combine to form new occupations in the future. They include roles like a counselor who specializes in helping people prepare for multistage lives beyond 100 years of age, and immersive experience designers who create content for new types of media. But that’s all rather speculative.

The Future of Skills, a new report from Pearson, looks optimistically at the employment landscape in the U.S. and U.K. (be sure to also check out the microsite for this report, which is well-done and a step above earlier reports).

The financial protection specialist company Unum, partnering with The Future Laboratory, has released a report, entitled “The Future Workplace: Key Trends That Will Affect Employee Well Being and How to Prepare fro Them Today.” The report examines in detail how the workplace is evolving and what employers need to do to manage employee well being in the next 15 years. The study was based on a survey of 1,000 British workers and insights from a group of leading experts from the Futures 100 Network.The report concludes that what is needed is “the rise of a workplace that is mindful, tranquil, sublime and that nurtures the health and performance of the mind.” This conclusion was based on the observation that workers are “turning away from their busy, hyper-connected, digital lifestyles and prioritizing personal fulfillment and well being instead. Workplace care in 2030 will need to deliver a new set of values. Instead of always on, there will be digital invisibility; instead of conversation, there will be contemplation; not only considered, but also sublime spaces; not only considerate, but also quiet companies.”

Mindful workers are feeling overwhelmed by the tools and means of communication they have to use on a daily basis, the report concludes. Employers need to stress the importance of regular breaks to improve productivity and allow employees to relax their minds for a while. In a clear change of direction, employers also need to establish an organizational culture in which overwork and workaholism is not only unappreciated, there should be company policies that prohibit it. Also, employees have consistently indicated, in numerous surveys, that they want greater control over their work time and personal time and would prefer “to work in an environment that supports flexible working and mixing of teams, rather than a set structure.”

Peter O’Donnell, CEO of Unum argues “The workplace is changing, becoming increasingly people-centric, so organizations competing for talent will need to be more supportive of their staff than ever before. Employers need to start taking now to adapt effectively to its evolution or they face significant financial repercussions.”

Tom Savigar, Chief Strategy Officer at The Future Laboratory and author of the report says, “An ageless and mindful workplaces is what British workers truly want to see their employers embracing so there is a clear need for businesses to augment how they care for the mind as well as the body to enable their staff to work better and for longer.”

So the work world of 2030 will be significantly different than it is today. It will no longer be business as usual, and no longer be work as usual. Be prepared for a rough but exciting ride.

PwC has spent some time envisioning four alternative future worlds of work, each named with a color. These admittedly extreme examples of how work could look in 2030 are shaped by the ways people and organizations respond to the forces of collectivism and individualism, on one axis, and integration and fragmentation on the other.

These scenarios can help organizations think through possibilities and how they will prepare to meet them. One prospect is that the world could move away from big company capitalism as technology enables small businesses and niche marketers to become more powerful. Or collectivism could take priority, as societies and companies work together through a sense of shared responsibility. Will “me first” prevail, or will societies come together for the greater good? Will digital technology mark the end for large companies, or will it enable large companies to slash their internal and external costs and become more powerful?

One thing is for sure. The world of work is about to be turned upside down, with potentially good things and bad things as results. Organizational awareness and government proactive action will have a significant impact on whether the results are good or bad.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.