By Ray Williams

February 27, 2021

The media is full of stories about super successful CEOs, such as Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson or Oprah Winfrey. They are however, the exception, not the norm. A large number of CEOs and senior executives have less than stellar careers, and an alarming number were outright failures. These failures had a significant negative impact on their organizations and their industries.

The question remains. What were the causes of these failures and derailments? This article will examine that question and propose some solutions.

I use the term failure or derailment in a leadership or executive role is defined as being involuntarily plateaued, demoted or fired below the level of expected achievement or reaching that level but unexpectedly failing. This article will use the terms leader, executive and CEO interchangeably.

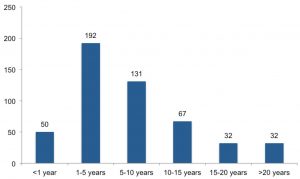

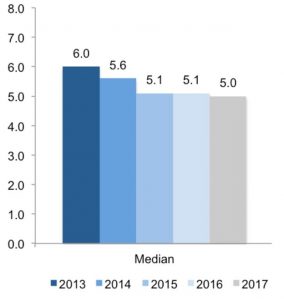

In the past two decades, 30% of Fortune 500 CEOs have lasted less than 3 years. Top executive failure rates are as high as 75% and rarely less than 30%. Chief executives now are lasting 7.6 years on a global average down from 9.5 years in 1995. According to the Harvard Business Review, 2 out of 5 new CEOs fail in their first 18 months on the job. It appears that the major reason for the failure has nothing to do with competence, or knowledge, or experience, but rather with hubris and ego and a leadership style out of touch with modern times. While the average tenure of HBR’s global top 100 CEOs is 17 years, the average tenure of S&P 500 CEOs is now around five years, a drop of 20 percent since 2013. Most such leaders tend to fail or get pushed out of the job long before the likes of the global top 100 even start to wobble. Long-lasting iconic leaders are the exception rather than the rule.

Booz Allen Hamilton concluded what they believe to be the most comprehensive study of CEOs. It reported for example, from 1995 to 2001:

- Turnover of the CEOs of major corporations increased by 53 percent.

- The number of CEOs departing because of the company’s poor financial performance increased by 130 percent.

- The average tenure of CEOs declined from 9.5 years to 7.3 years.

- In Europe, where corporate chiefs are presumed to be more protected by intimate relationships among senior management, boards, governments, and financial institutions. In the Asia/Pacific region, where such relationships also are presumed to exist, changes in CEO careers and CEO turnover have been minimal.

CEO Performance Issues

Leadership has been a heavily researched topic for over 50 years. As a result, over 15,000 articles and books have been published on this topic. We know a lot about the characteristics of successful leaders. And based on this knowledge, organizations spend an estimated $50 billion a year on the development of leaders (Fulmer and Conger, 2004).

In spite of this knowledge and investment, most organizations feel they have a shortage of effective leaders. It has been estimated that between 50 and 75 percent of leaders are not performing well (Hogan and Hogan, 2001). The number of leaders that get fired for failing to perform has increased over the past decade and the tenure of organizational leaders has steadily dropped (Hogan, 1999).

The American based Institute for Policy Studies who publish annual “Executive Excess” reports (based on 241 CEOs in the 25 highest paying jobs over 25 years) called Bailed Out, Booted and Busted found that 22% had been Bailed Out (ceased to exist or received taxpayer bailouts), 8% were sacked (lost their jobs involuntarily) and 8% Busted (paying significant fines or settlements).In other words, 38% were seriously poor performers.

What are the causes of CEO Failure?

Studies show CEOs with MBAs more likely to fail. McGill Management Professor Henry Mintzberg, on his blog, says there’s significant evidence that MBA CEOs are not as effective as counterparts without the degree. Prof. Mintzberg has long been a critic of the degree that most people in business consider an important prerequisite for success. He has refused to teach MBA students, arguing teaching MBAs involves teaching the wrong people the wrong things at the wrong time, and has written a book critical of such programs. With Joseph Lampel of Manchester Business School, he studied 19 Harvard Business School alumni who had been considered business superstars in 1990 – top performers with a lustrous MBA education.

Looking at how they fared in ensuing years, he found that a majority, 10, seemed to have clearly failed — their company went bankrupt, they were forced out of the CEO chair, a major merger backfired, or some similar significant setback occurred. Four others had questionable performance, meaning that 14 out of 19 stars had failed to shine. “Some of these 14 CEOs built up or turned around businesses, prominently and dramatically, only to see them weaken or collapse just as dramatically,” he writes.

Of course, that was just one sample and one study. But now he notes two other business professors — Danny Miller of Montreal’s HEC business school and Xiaowei Xu of the University of Rhode Island – have completed studies with much larger samples and even more troubling results. In the first, they studied 444 CEOs who had been celebrated on the covers of Business Week, Fortune and Forbes from 1970 to 2008. They compared the subsequent performance of those companies that were headed by MBAs – one quarter of the sample – with those that weren’t. Both sets of companies declined in performance after hitting the cover. “It’s hard to stay on top,” Prof. Miller has noted. But the ones headed by MBAs declined more quickly and the performance gap remained significant even seven years after the cover story.

The research suggests an association between the MBA degree and a desire to achieve growth via acquisitions, leading to reduced cash flows and inferior return on assets. But if the companies suffered financially, the CEOs with MBAs didn’t — their compensation increased about 15 per cent faster than the others. “Apparently they had learned how to play the ‘self-serving’ game, which Miller referred to in a later interview as ‘costly rapid growth,'” Prof Mintzberg says.

The second study was broader and more recent, looking at 5,004 CEOs of major United States public corporations from 2003 to 2013. The results were much the same. The researchers report, “MBA CEOs are more apt than their non-MBA counterparts to engage in short-term strategic expedients such as positive earnings management and suppression of R&D, which in turn are followed by compromised firm market valuations.” And again, they were well-rewarded for this non-performance.

Prof Mintzberg notes that business schools are centers of inter-disciplinary work, and their MBA programs “do well in training for the business functions, such as finance and marketing, if not for management.” Something in their training may be leading to the poor results. Still, with so many of their graduates getting to the top – if not necessarily staying there – the incentive to change is small. But he argues the problems the studies point to are significant: “Too many of their graduates are corrupting the economy.”

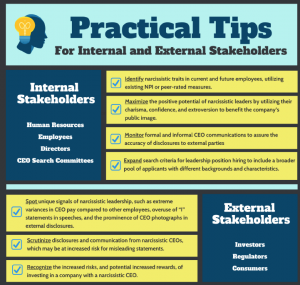

According to Michael Jarrett, INSEAD Professor of Organizaitonal Behavior, writing in the INSEAD publication, “the prevailing arguments used to explain success or failure mostly concern the CEOs’ personalities, especially transformational leadership characteristics, such as passion, risk-taking and tenacity. The failures are believed to be due to simple incompetence, rigidity, hubris or narcissism, traits that made the CEOs deaf to the changing world around them.” He goes on to say that a string of success or a good early start can fuel CEO narcissism and hubris.

According to Sydney Finkelstein, author of Why Smart Executives Fail, researched several spectacular failures during a six year period. He concluded that these CEOs had similar deadly habits:

- Habit 1: They see themselves and their companies as dominating their environment. Warning sign: A lack of respect for others .

- Habit 2: They identify too closely with the company, losing the boundary between personal and corporate interests. Warning sign: They define themselves by their job.

- Habit 3: They think they are the only ones that have all the right answers. Warning Sign. They have few followers.

- Habit 4: They ruthlessly eliminate anyone who isn’t completely supportive. Warning Sign: A lot of subordinates are either fired or quit.

- Habit 5: They are obsessed with photos, speeches, appearances and publications in which they represent the company. Warning Sign: They blatantly seek out media.

- Habit 6: The underestimate obstacles. Warning Sign: Excessive hype and little substance.

- Habit 7: They stubbornly rely on past achievements and successes. Warning sign: They consistently refer to what worked for them in the past.

Finkelstein goes on to say “executives often learn the wrong lessons from history. The costs associated with such misdirected learning are significant, and often tally in the hundreds of millions to billions in losses. These mistakes are seldom due to managerial incompetence or random events, but rather are driven by common patterns of managerial behavior.”

David Dotlich and Peter C. Cairo, in their book,Why CEOs Fail: The 11 Behaviors That Can Derail Your Climb To The Top And How To Manage Them, present 11 cogent reasons why CEOs fail, most of which have to do with hubris, ego and a lack of emotional intelligence. These are:

- Arrogance—they think that they’re right, and everyone else is wrong.

- Melodrama—they need to be the center of attention.

- Volatility—they’re subject to mood swings.

- Excessive Caution—they’re afraid to make decisions.

- Habitual Distrust—they focus on the negatives.

- Aloofness—they’re disengaged and disconnected.

- Mischievousness—they believe that rules are made to be broken.

- Eccentricity—they try to be different just for the sake of it.

- Passive Resistance—what they say is not what they really believe.

- Perfectionism—they get the little things right and the big things wrong.

- Eagerness to Please—they try to win the popularity contest.

Dotlitch and Cairo show that even great leaders can derail their careers by exhibiting flawed behaviors which are often closely related to the factors that made them successful so far. They say leadership failure is primarily a behavioral issue. Leaders fail because of who they are and how they act, particularly when they are under stress. All leaders are vulnerable to the eleven derailment factors; these are deeply ingrained personality traits that affect their leadership style and behaviors. But identifying and managing these derailers is possible and failure can be prevented Dotlitch and Cairo argue.

Barbara Kellerman, in Bad leadership: what it is, how it happens, why it matters focused on two basic categories of bad leadership, ineffective and unethical, identifying seven types of bad leaders that are most common:

- Incompetent – lack will or skill to create effective action or positive change.

- Rigid – stiff, unyielding, unable or willing to adapt to the new.

- Intemperate – lacking in self-control.

- Callous – uncaring, unkind, ignoring the needs of others

- Corrupt – lies, cheats, steals, places self-interest first.

- Insular – ignores the needs and welfare of those outside the group.

- Evil – does psychological or physical harm to others.

Kellerman says the first three types of bad leaders are incompetent; the last four types are unethical. Incompetent leaders are the least problematic (damaging) while unethical or amoral leaders are the most problematic (damaging). Ineffective leaders fail to achieve the desired results or to bring about positive changes due to the means falling short. Unethical leaders fail to distinguish between right and wrong. Ethical leaders put followers needs before their own, exhibit private virtues (courage, temperance) and serve the interests of the common good. Kellerman argues that the unethical leaders have caused the most damage to organizations.

Joyce Hogan and Robert Hogan have written extensively on leadership failure. They conclude, based on a review of the work of others and their own research, that when leaders fail they do so because they are unable to understand other people’s perspectives. They lack socio-political intelligence. This produces an insensitivity to others which limits their abilities to get work done through others. Work colleagues do not like or do not trust (or both) the leader.

Researchers Cynthia McCally and Michael Lombardo identified the ten most common causes of leadership derailment:

- An insensitive, abrasive, or bullying style.

- Aloofness or arrogance.

- Betrayal of personal trust.

- Self-centered ambition.

- Failure to constructively address an obvious problem.

- Inability to select good subordinates.

- Inability to take a long-term perspective.

- Inability to adapt to a boss with a different style; and

- Overdependence on a mentor.

M.L. Najjar et al., using Hogan and Hogan’s Hogan Development Survey, examined the relationship of leaders dysfunctional interpersonal tendencies and multi-rater evaluations. The sample included 295 high potential senior executives from a Fortune 500 company. Raters included immediate supervisors and a composite group of peers and others familiar with the individual’s job performance. Criteria included four leadership factors (business results, people, self) and eleven interpersonal factors (e.g. trusting, resilient, dependable). Four broad hypotheses were considered:

- characteristics associated with arrogance will be associated with lower peer ratings;

- characteristics associated with cautiousness will be associated with lower supervisor and peer ratings;

- characteristics associated with excitability will be associated with lower supervisor and peer ratings; and

- characteristics associated with skepticism and distrust will be associated with lower peer ratings.

Their results showed that dysfunctional behaviors associated with arrogance, cautiousness, volatility, and skepticism negatively affected performance ratings the most.

Thomas Chidester and colleagues examined the personality characteristics of more and less effective commercial airline flight crew. Effectiveness was defined by the number and severity of errors made by the crew. Captains of crews with the fewest errors were described as warm, friendly, self confident and coped well with pressure. Captains of crews with the most errors were described as arrogant, hostile, boastful, egotistical, dictatorial and passive aggressive.

The psychological literature on leadership derailment and failing leadership borrows many ideas from psychiatry and psychoanalysis. Seventy-five years ago the German born Freudian Karen Horney argued that children develop three normal and spontaneous patterns of relating to others. The three trends have been labelled moving away from others, moving against others, and moving toward others. The moving away trend consists of coping mechanisms characterized by isolation and pulling away from others to avoid situations that provoke basic anxiety.

The moving against trend has a basic hostility and mistrustfulness at its center. People, she argued, characterized by this trend cope with their basic anxiety by seeking power and control over others. The third trend of moving toward others is characterized by inhibition of own needs to appease others at almost any cost. Horney’s theory explains why individuals consistently act in accordance with the derailment tendencies, even when it has obvious negative consequences.

Many aspiring CEOs rejoice in their tough image: a person who “kicks ass”, get things done and isn’t swayed by sentimentality. Many shareholders warm to the idea of a no-nonsense boss happy to take-on the many “people problems” in the organization.

The second pattern that Horney identified is arrogance: hubristic, self-centered, pompous. We all want in our leader self-confidence and a person “comfortable” in their own skin. We admire people with self-belief who is is not held back by self-doubt and dithering.

The third pattern is theatricality: varying expressions of emotionality, dramatic, show offs. The media likes the expression of passion; the boss who can appear totally committed to their business. They also like quirky expressions of special clothes and personal styles.

The data suggest that these three characteristics, in moderation, are extremely helpful in a business career. Of course, one needs to be bright, hard-working, ambitious etc, but these three characteristics give one a boost.

Indeed, there are studies from Britain, Denmark and New Zealand, all of which correlate with these ideas.

The story goes like this. If an executive has an optimal amount of these factors often called tough, self-confident and passionate, they can be rewarded by success. We learn little from success except to keep doing what we did. Failure is a good teacher. So being promoted and being initially successful tends to push the potentially derailing executive over the limit where confidence turns into narcissism; toughness into psychopathy and theatricality into hysteria.

In my new book, Toxic Bosses: Practical Wisdom for Developing Wise, Moral and Ethical Leaders, I describe the growing virus of CEO unethical and amoral behaviour as a major cause for their failure. In addition, I show how organizations have often chosen psychopaths, sociopaths, and malignant narcissists to leader the organizations, often with a disastrous result.

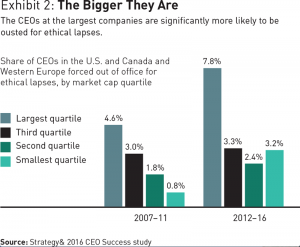

Research has shown that for decades the main reason chief executives were ousted from their jobs was poor financial performance of the firm. In 2018, that changed. Personal misconduct occurring in the #MeToo era is now the biggest driver behind a chief executive falling from the top.

That’s according to a new study from the consulting division of PwC, one the nation’s largest auditing firms. It is the first time since the group began tracking executive turnover 19 years ago that scandals over bad behavior rather than poor financial performance were the leading cause of leadership dismissals among the world’s 2,500 largest public companies.

“A lot of bad actors are being cleared out of the reaches of corporate America,” John Paul Rollert, a professor at the University of Chicago who studies the ethics of leadership, told NPR.

Thirty-nine percent of the 89 CEOs who departed in 2018 left for reasons related to unethical behavior stemming from allegations of sexual misconduct or ethical lapses connected to things like fraud, bribery and insider trading, the study found.

The shift from poor financial performance of firms being the reason why CEOs were terminated is only about 25% of the time. And that shift, the researchers say, is meaningful. Increasingly, according to the study, corporate boards are approaching allegations of executive misconduct with a “zero-tolerance stance,” fueled in part by societal pressures since the rise of the #MeToo movement.

“For companies, they are recognizing that if they don’t get aggressive with this type of behavior, they are going to face exceptional liabilities when it comes to court cases,” Rollert said. “And so better to address these concerns now than to deal with multi-million-dollar lawsuit and the bad PR that comes with that sometime down the road.”

Some former CEOs say the study is proof that more women are feeling emboldened to share stories of alleged abuse or misconduct, and it is reshaping corporate America.

“Employees are starting to say, ‘how can you enforce a policy on us without holding CEOs accountable?’ ” said Bill George, a senior fellow at Harvard Business School and former chief executive of Medtronic, who has served on the boards of Goldman Sachs and Exxon Mobil. “The CEO’s behavior has to be beyond reproach. Boards are aware of this and are really feeling pressure around that now,” George explained.

A study by He Bin and Sun Xu published in the Frontiers of Psychology concluded “Unethical pro-organizational behavior” (UPB) can now be defined as ‘actions that are intended to promote the effective functioning of the organization or its members (e.g., leaders) and violate core societal values, norms, laws, or standards of proper conduct’, such as a tendency to exaggerate the truth about one’s company’s products or services to customers and clients to benefit one’s company.”

Such behavior appears to help the organization in the short term, the researchers argue, but it comes at a high cost to the business in the long run. Furthermore, He Bin and Sun Xu argue, organizations often develop norms that tolerate the violation of moral standards if it is beneficial to the organization. Studies have shown that, when people are surrounded by the unethical behavior of their peers, they are likely to imitate the behavior of these peers, because such behaviors demonstrate apparently appropriate organizational norms. Therefore, when observing UPB, subordinates will likely consider such behavior to be what the organization expects them to do, and they may then follow and engage in UPB themselves.

As the saying goes, with great power comes great responsibility — and yet it seems like so many powerful people use their power for evil, not good. But a new study suggests that tweaking how powerful people think about their power could affect how they act.

Simply put, researcher Miao Hu contends in his study published in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,“making people in power think about how they should act (as opposed to how powerful people generally do act) may help them act more ethically”.In the study, researchers asked participants to describe how people in power act and also to describe how people in power should be expected to act.

Hu, an assistant professor of marketing at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and the lead author on the study, found that when people were in the position of power and were asked to think about how they would act, they were more ethical. That is, they were more likely to lie about their behavior than were those who were not in a position of power. When the people in the position of power were asked to think about how they should act, on the other hand, they acted more ethically.

“Making people in power think about how they should behave may serve as a potential form of preventative medicine against the abuse of power.”—Miao Hu

How the Media Has Fuelled Unethical Leader Behaviour

Stephen Chen, writing in the Journal of Public Affairs, says misreporting of a firm’s financial performance increases the CEO’s confidence which in turn increases the need to misreport performance in order to feed an ever increasing ego. This growth can be fuelled by statements by third party financial analysts and the press which praise their actions. And the actions are not restricted to financial data.

These ethical issues include women exploitation, subliminal perception, and advertising to children, and deceptive advertising. The fact that potentially unethical advertisements are reaching the marketplace suggested that current methods of evaluating advertisements may be insufficient for some of today’s controversial or innovative campaigns.

In its more corrosive application — the one that is inculcated in many business schools, and enforced by corporate lawyers and demanded by activist investors and Wall Street analysts — maximizing shareholder value has meant doing whatever is necessary to boost the share price this quarter and the next. Over the years, an exclusive focus on shareholder value has been used to justify cheating or deceiving customers, squeezing workers and suppliers, avoiding taxes and lavishing stock options on executives. Most of what people find so distasteful about American capitalism — the ruthlessness, the greed, the inequality — has its roots in this misguided and twisted notion that business only exists for financial gain for the shareholders (and greedy CEOs).

In an article entitled “Bolstering unethical leaders: The role of the media, financial analysts and shareholders,” in the Journal of Public Affairs, researcher Stephen Chen describes cites several high profile accounting scandals such as Enron, WorldCom. Chen asserts that the problems resulting from financial incentives and CEO narcissism are accentuated by reports by external parties such as financial analysts and the financial press because increasingly many CEOs are now assessed on the achievement of earnings targets set by financial analysts and investors.

According to a 2006 Business for Social Responsibility brief, “Corruption and Bribery”, an organization has many reasons for operating ethically, including avoiding fines and litigation, reducing damage to the firm’s reputation, protecting or increasing capital and shareholder value, direct and indirect cost control, creating a competitive advantage, and avoiding internal corruption.

On the other hand, unethical behavior in firms results in lower productivity, especially among highly skilled employees, according to “The Relationship of Ability and Satisfaction to Job Performance”, in the Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, by Philip E. Varca and Marsha James-Valutis.

Unethical behavior also results in lower long-term financial performance as measured by metrics such as economic value-added, and market value-added as shown in the 2003 study “Does Business Ethics Pay?” in the Institute of Business Ethics, by Simon Webley and Elise More.

All of these are documented results of unethical business behavior according to “The Wealth Effects of Unethical Business Behavior,” in the Journal of Economics and Finance, by Michael D. Long and Spuma Rao.

Edson Spencer, former chairman of Honeywell, in his article “The Hidden Costs of Organizational Dishonesty” in the Sloan Management Review, argues it takes years to build a reputation for integrity that can be lost overnight.

And once an organization loses its reputation for integrity, the effect can be permanent, according to the 2004 Josephson Institute report, “The Hidden Costs of Unethical Behavior.”

As senior executive unethical behaviors flourish, workers throughout the organization note them, almost as permission to replicate, and unethical behavior becomes a cultural norm. Ultimately, this culture results in detrimental behaviors such as under delivering on promises, turf-guarding, goal-lowering, budget-twisting, fact-hiding, detail-skipping, credit-hogging, and scapegoating, according to studies conducted by the Online Center for Engineering and Science at Case Western Reserve University.

The U.S. Ethics and Compliance Initiative, (ECI) the oldest nonprofit in the ethics & compliance industry is a research and membership organization comprised by institutions across every sector, each dedicated to promoting the highest levels of integrity in their operations. ECI has provided some startling data regarding the presence of unethical practices in U.S. organizations.

According to ECI, the single biggest influence on employee conduct is the organization’s culture. In strong ethical cultures, wrongdoing is significantly reduced. Yet only one in five employees, according to ECI’s study of American business, indicate that their company has such an environment. This status remains largely unchanged over the past decade. Furthermore, in 2017, 40% of employees believed that their company had a weak ethical culture, a trend that has not notably changed since 2000.

In an article in The New Yorker, Robin Wright asks the question, “Is America Becoming a Banana Republic?” She says, “the chief principle of ‘banana-ism’ is that of ‘kleptocracy’, whereby those in positions of influence use their time in office to maximize their own gains, always ensuring that any shortfall is made up by those unfortunates whose daily life involves earning money rather than making it.” She concludes the United States clearly fits those descriptors.

Unethical Executive Behaviour Spreads Like a Virus

The National Business Ethics Survey of nearly 4,700 employees at by the Ethics Resource Center (ERC), an independent research firm for the advancement of high ethical standards and practices in public and private organizations, has revealed thepercentage of companies with a weak ethical culture is on therise, as is the number of employees who experienced retaliationfor blowing the whistle on observed misconduct. The report concluded that “American business may be on the cusp of a large downward shift in ethical conduct.”

Among the other conclusions of the report were the following:

- The five most frequently observed misconduct events were misuse of company time (33%); abusive behavior (21%); company resource abuse (20%); lying to employees (20%); and violating corporate Internet use policies (16%).

- The proportion of employees who observed misconduct and then decided to report it climbed to a record high of 65%.

- Nearly 70% of workers who witnessed violations involved stealing or improper payment offers to public officials.

- Almost two-thirds of employees reported: Improper use of competitors’ inside information; the falsification of expense reports; trading on inside information; making improper political contributions; delivery of goods or services that failed to meet specifications; abusive behavior or behavior that creates a hostile work environment; and the falsification and/or manipulation of financial reporting information.

- Many of the retaliatory actions were severe: exclusions from decisions and work activity by supervisor or management (64%); verbally abused by supervisor or someone else in management (62%); verbally abused by other employees (51 %); experienced online harassment (31%); experienced physical harm to their person or property (31%); and harassed at home (29%).

- Further, the NBES reported the percentage of employees who perceived pressure to compromise their company’s ethical standards, or even break the law so they could perform their jobs, jumped significantly from 13% in 2011 to 29% in 2017.

- As expected, there’s a very strong correlation between a strong ethical culture and lower observed misconduct. Misconduct was observed in only 29% of companies with a strong ethical culture but seen in 90% of those with a weak ethical culture.

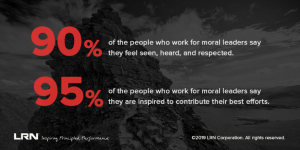

Celia Moore and her colleagues published an article in theJ ournal of Applied Psychology entitled “Leaders Matter Morally: The Role of Ethical Leadership in Shaping Employee Moral Cognition and Misconduct,” and concluded among other things, “leaders with low-ethical standards might amplify their subordinates’ propensities to morally disengage.”

For instance, Moore states, if one has a leader who defines success in terms of results rather than the means through which they are obtained, subordinates could more easily morally justify short-changing customers in the interest of profit. Moore found that leaders who demand obedience or absolute loyalty from their subordinates facilitate their subordinates’ displacement of responsibility, such that individual employees can shift their moral agency onto their domineering leader. A leader who refers to clients or competition as a resource to be exploited or an enemy to be overcome can support euphemistic labeling of harmful practices or the attribution of blame for mistreatment onto those whom they are harming.

Reasons Why We Choose Unethical Leaders

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Chief Talent Scientist at Manpower Group and a Professor of Business Psychology at University College London (UCL) and Columbia University, unpacks the psychology of why we don’t choose leaders with the highest integrity.

Here are some of the reasons he cites:

- We are not serious about integrity. While we love to say that integrity is a cornerstone of leadership potential, our order of preference, when we vote or appoint leaders, prioritizes other traits. In fact, he says, many of the qualities that seduce us in leaders are diametrically opposed to integrity.

- We are seduced by narcissistic and psychopathic leaders. As he shows in his latest book or related TED talk, we have a tendency to gravitate towards charismatic and magnetic personalities, usually big egos, who can captivate us with their megalomaniac visions and delusional talents. Although it is perfectly possible for charismatic leaders to be ethical, when we select leaders on charisma rather than humility, and confidence rather than competence, we should not be surprised that we end up with a lot of unethical and self-centered people in charge, who are quite happy to take advantage of others to advance their own selfish interests.

- Too many people become leaders to acquire status and power. Scientists have always regarded leadership as a psychological process of influence whereby an individual enables a group of people to elevate their performance and accomplishments by directing them to function as a cohesive unit. And in politics, leadership brings societies together to propel them to progress and prosperity.

But there is a problem, Chamorro-Premuzic says. Leadership is marketed as the ultimate career destination, and it confers power and status, so there are a great number of individuals who are only interested in becoming leaders to acquire fame and status. They have no desire to make others better and are entirely focused on their own personal success. The more we pretend that leadership is an unselfish and other-oriented role, the more these individuals will fake integrity in order to climb up the ladder.

Chamorro-Premuzic contends: “When leaders emerge to co-opt our own selfish interests, we are quite happy to leave aside higher moral principles, and optimize for our own personal success. This is how a single rotten apple can contaminate the whole barrel, and why good apples go bad when you put them in a rotten barrel. The effects of leadership always cascade down, and corrupt leaders are very good at unleashing their teams’ parasitic mindset. In politics, it is often said that most countries have the government they deserve. At least in democracies, we can see why corrupt leaders would be more likely to emerge in societies with corrupt rather than altruistic values.”

In an article published in the Harvard Business Review, “Overconfidence is Contagious,” by Joey T. Cheng, Elizabeth R. Tenney, Don A. Moore and Jennifer M. Logg, they report their detailed research of why the famous American company Enron collapsed. Their search for answers leads consistently to Enron’s top executives, Jeffrey Skilling and Kenneth Lay, whose massive acts of accounting fraud, corruption, and deception covered up the company’s weaknesses until their exposure led to its downfall.

But a deeper analysis reveals the dysfunctional corporate culture that made it all possible. A “culture of arrogance” permeated the organization, and many employees felt like they were part of an elite group and believed they were smarter than everybody else. This culture of bravado drove employees to aggressively negotiate deals with questionable financials and take on increased risks under the illusion of invincibility. An abundance of research reveals that overconfident leaders put their firms at risk.

Their research shows the havoc these unethical executives create extends beyond their own reckless decision making — they may be the first domino to fall, influencing their employees who in turn influence their peers. Inspiring a culture of overconfidence in this way fuels greater peril.

One lesson, the authors, say, from the story of Enron is that the success of an organization depends on cultivating the right social climate and norms — norms that promote grounding in reality and freedom from delusions of grandeur.

There is research evidence that shows a connection between unethical behavior and a selfishness of rich and powerful people.

My Experience as an Executive Coach

I’ve had the opportunity over the last two decades to work with C-Suite leaders including CEOs in a coaching capacity. Most were very self-aware, had exceptional relationships with other, and a high level of emotional intelligence. Some however, ere deficient in those areas, and my work with them amounted to “remedial” work, usually as a result of a superior’s or the Board’s insistence. I can say with some satisfaction that I was able to help those individuals change behaviours, and become better leaders. Others I was less successful with, and in all those cases, the prime causes for their failure were hubris, unethical behaviour, a lack of empathy and compassion for others, and an Anti-Social Personality Disorder (psychopath, sociopath, malignant narcissist).

What to Do About the Problem

Hogan et al. (1994) believe that dark side characteristics can be changed but that this requires more intensive development than currently found in most leader training programs. They cite evidence from the Coaching for Effectiveness Program at Personnel Decisions Inc. (Peterson, 1993; Peterson and Hicks, 1993), based on work with 370 managers over a five year period which showed that most managers were able to change a number of targeted behaviors.

There needs to be a rigorous culture of open and transparent feedback about the CEO’s performance, and the CEO needs to be encouraging that to happen. All to often, the CEO is neither open to nor receives critical feedback and receives only the positive or self-serving comments from employees.

The Board of Directors and particularly the Chairman of the Board also need to take their responsibility of oversight of the firm and supervision of the CEO more seriously.

There are no universal ways to prevent failures, except perhaps to be alert for the warning signs. We live in a celebrity culture where executives are expected to be perfect, and larger than life. We don’t like to admit they have flaws. We crave heroes and contribute to their heroic myth when we can’t see their flaws.

Good leaders make people around them successful. They are passionate and committed, authentic, courageous, honest and reliable. But in today’s high-pressure environment, leaders need a confidante, a mentor, or someone they can trust to tell the truth about their behavior. They rarely get that from employees or board members.

Professional executive coaches can help leaders reduce or eliminate their blind spots and be open to constructive feedback, not only reducing the likelihood of failure, and premature burnout but also provide an atmosphere in which the executive can express fears, failures and dreams.

In my book, Toxic Bosses, I provide an extensive list of suggestions on how to avoid the mistake of hiring unethical or incompetent leaders who end up failing, or if you have one, what to do about it.

Here’s a partial list of suggestions:

- Place an emphasis on integrity in behaviors—demand it of ourselves and those who we work with and lead us.

- Stop recruiting overconfident, narcissistic and sociopathic/psychopathic people for leadership positions in our institutions and organizations, and opt instead for the honest, humble and compassionate leaders.

- Recruit and promote more women into leadership positions. Research has shown that female leaders are less prone to corrupt and unethical behavior.

- Engage in a serious overhaul of the current capitalistic system which has a structure and practices that facilitate amoral and unethical behavior, and unwise decisions to the detriment of the populace and the planet. In particular, shareholder interests as the primary driver for business decisions must be abandoned. Encourage business organizations to complete a serious overhaul of their current ethical principles and policies.

- Encourage business schools to put more emphasis on the study of humanities including philosophy and ethics; provide more support for the humanities in post secondary education rather than the current emphasis on technical knowledge and expertise in business.

- Encourage business leaders (and their employees) to become more involved in worthy causes that benefit society and the planet that are not tied to economic or financial gain.

- Enact stronger laws, policies, regulations and procedures to protect whistle blowers who witness or encounter unethical (or amoral) organizational practices.

- Emphasize the importance of developing self-awareness and emotional intelligence in leadership development programs and training.

- Encourage leader practices that promote exposure to various forms of ethnic and cultural (and gender) diversity.

- Encourage public school system to include in both teacher training and curriculum the teaching of civics, moral and ethical behavior, critical thinking and Socratic dialogue.

- Encourage of public school system to initiate curriculum and practical experiences for students aimed at social good and environmental protection.

- Engage in “good conversations” about moral values, and ethical behavior.

- Exposure to the complexity of whole systems, rather than only discrete small parts or functional area.

- Study significant issues from an integrated perspective rather than a narrow perspective.

- Work collaboratively with others on significant problems or challenges that impact the welfare of all.

- Develop excellence in listening and perspective-taking.

- Work as a volunteer on an issue or project that benefits others, humanity and/or the planet without the need for recognition or compensation.

- Actively engage in the responsibilities of being a citizen in a democracy.

- Be an advocate for justice and fairness for all.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest books:

Toxic Bosses: Practical Wisdom for Developing Wise, Moral and Ethical Leaders,

and,

Available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.