Why Perfectionism is So Damaging and What to Do About It

By Ray Williams

As a culture, we tend to reward perfectionists for their insistence on setting high standards and relentless drive to meet those standards. And perfectionists frequently arehigh achievers — but the price they pay for success can be chronic unhappiness and dissatisfaction.

“Reaching for the stars, perfectionists may end up clutching at air,” psychologist David Burns warned in a 1980 Psychology Today essay. “[Perfectionists] are especially given to troubled relationships and mood disorders.”

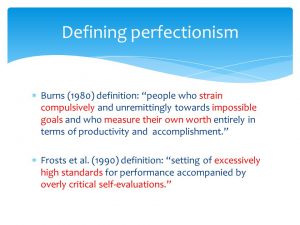

Definitions

Perfectionismis a personality trait characterized by a person’s striving for flawlessness and setting high performance standards, accompanied by critical self-evaluations and concerns regarding others’ evaluations. It is best conceptualized as a multidimensional characteristic, as psychologists agree that there are many positive and negative aspects. In its maladaptive form, perfectionism drives people to attempt to achieve unattainable ideals or unrealistic goals, often leading to depression and low self-esteem. By contrast, adaptive perfectionism can motivate people to reach their goals, and to derive pleasure from doing so.

Research

Perfectionists strain compulsively and unceasingly toward unobtainable goals, and measure their self-worth by productivity and accomplishment. Pressuring oneself to achieve unrealistic goals inevitably sets the person up for disappointment. Perfectionists tend to be harsh critics of themselves when they fail to meet their standards.

E. Hamachek in 1978 argued for two contrasting types of perfectionism, classifying people as tending towardsnormalperfectionism or neurotic perfectionism. Normal perfectionists are more inclined to pursue perfection without compromising their self-esteem, and derive pleasure from their efforts. Neurotic perfectionists are prone to strive for unrealistic goals and feel dissatisfied when they cannot reach them. Hamachek offers several strategies that have proven useful in helping people change from maladaptive towards healthier behavior.

Contemporary research supports the idea that these two basic aspects of perfectionistic behavior, as well as other dimensions such as “non-perfectionism”, can be differentiated. They have been labeled differently, and are sometimes referred to as positive striving and maladaptive evaluation concerns, active and passive perfectionism, positive and negative perfectionism, and adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism. Although there is a general perfectionism that affects all realms of life, some researchers contend that levels of perfectionism are significantly different across different domains (i.e. work, academic, sport, interpersonal relationships, home life).

Other researchers such as T. S. Greenspon disagree with the terminology of “normal” vs. “neurotic” perfectionism, and hold that perfectionists desire perfection and fear imperfection and feel that other people will like them only if they are perfect.For Greenspon, perfectionism itself is thus never seen as healthy or adaptive, and the terms “normal” or “healthy” perfectionism are misnomers, since absolute perfection is impossible. He argues that perfectionism should be distinguished from “striving for excellence”, in particular with regard to the meaning given to mistakes. Those who strive for excellence can take mistakes (imperfections) as incentive to work harder. Unhealthy perfectionists consider their mistakes a sign of personal defects. For these people, anxiety about potential failure is the reason perfectionism is felt as a burden.

The book Too Perfect: When Being in Control Gets Out of Control by Jeanette Dewyze and Allan Mallinger contends that perfectionists have obsessive personality types.Obsessive personality type is different from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in that OCD is a clinical disorder that may be associated with specific ritualized behavior or thoughts. According to Mallinger and DeWyze, perfectionists are obsessives who need to feel in control at all times to protect themselves and ensure their own safety. By always being vigilant and trying extremely hard, they can ensure that they not only fail to disappoint or are beyond reproach but that they can protect against unforeseen issues caused by their environment. Vigilance refers to constant monitoring, often of the news, weather, and financial markets.

The relationship that exists between perfectionistic tendencies and methods of coping with stress has also been examined with some detail. One recent study found that college students with adaptive perfectionistic traits, such as goal fixation or high standards of performance, were more likely to utilize active or problem focused coping. Those who displayed maladaptive perfectionistic tendencies, such as rumination over past events or fixation on mistakes, tended to utilize more passive or avoidance coping. Despite these differences, both groups tended to utilize self-criticism as a coping method. This is consistent with theories that conceptualize self-criticism as a central element of perfectionism.

According to psychologist Pavel G. Somov, there are four types of perfectionism. The first three of these are essentially “software” problems. The solution to “software-type” perfectionism is “re-programming.” The Hyper-Attentive type of perfectionism is a “hardware” (brain) issue.

Neurotic Perfectionism

Neurotic perfectionism is motivated by “the need for approval” (Flett & Hewitt, 2002). Neurotic perfectionism parallels the Conscientious Compulsive variant of OCPD (Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder).Such individuals exhibit “a conforming dependency, a compliance to rules and authority, and a willing submission to the wishes, values, expectations and demands of others.” They have “a strong sense of duty, which masks underlying feelings of personal inadequacy.” They fear “that failure to perform perfectly will lead to both abandonment and condemnation” by others (Millon et al., 2000).

Neurotic perfectionists aren’t wimps. They are wounded egos. They are casualties of poor parenting, societal pressures, and possibly of abuse. They have been programmed and conditioned to feel bad about themselves and to please, appease, accommodate others. For example, a neurotic perfectionist might spend a sleepless night worrying about the gift he bought his wife for their anniversary, and convince himself, by the end of the night, that it’s insultingly cheap, that she’ll hate it, and he must return it for something better, more perfect, or else she might leave him which will confirm that he is unlovable.

Narcissistic Perfectionism

Remember that Greek myth of Narcissus who was so enamored by the reflection of his own image in a pond that he was unable to stop marveling at it? Narcissists thrive on mirrors. No, not necessarily on the physical mirrors, but on the mirrors of social feedback.

Contrary to the common misperception, narcissists aren’t arrogant even if they act arrogant. They simply don’t feel good about themselves. If you are recognizing yourself in this, chances are you grew up with a narcissistic parent. Most narcissists are tragically the children of narcissists. Growing up with an insecure parent, you might have lost your sense of self because your sense of self was in the service of being a mirror for your parent’s frail ego. And now, just like your parents, perhaps, the only way for you to feel special is to command special treatment, to insist on unquestioning compliance with your wishes from others, to demand nothing less than perfection from others.

Clinically, narcissistic perfectionism parallels the Bureaucratic Compulsive variant of OCPD. Bureaucratic Compulsives, as the name suggests, thrive on hierarchical superiority. For example, they are eager to show off their “knowledge of the rules;” they are “effectiveness with red tape;” “punctual and meticulous;” they tend to appraise “their own and other’ tasks with black-and-white efficiency, as done or not done” (Millon, 2000).

In sum, they are intolerant of imperfection as they feel it reflects unfavorably on them. If they are perfect and everything around them is perfect, then others will respond to them as perfect, and then, and only then, will they buy into the perfect reflection in the social mirror and finally feel good about themselves, if only for a brief moment.

Principled Perfectionism

Principled perfectionism is perfectionism about ethics and morality. Principled perfectionists feel so passionately about what they believe that they run the risk of imposing their beliefs onto others. They strive for moral perfection and demand nothing less of themselves. As a result not only are they really hard on themselves but they may be also rather judgmental of others’ imperfections.

Principled perfectionists run a close parallel to Puritanical Compulsives who can be characterized as self-righteous, zealous, uncompromising, indignant, dogmatic, and judgmental (Millon, 2000). Principled perfectionism also parallels the so-called “world-oriented perfectionism,” which is defined as “the belief that precise, correct, and perfectsolutions to all human and world problems exist” (Flett & Hewitt, 2002). If you are recognizing yourself in this, don’t feel too bad: idealism is just innocence and righteousness is, in essence, enthusiasm. You aren’t bad for wanting to save the world.

Hyper-Attentive Perfectionism

Perfectionism may be related to a particularly hyper-attentive cognitive style. It has been noted that some compulsives are so good at concentrating that they cannot stop concentrating, that “they can’t skim a page, they must scrutinize every word” (Maxment & Ward). Individuals with this type of stimulus-bound cognitive style are “easily distracted and disturbed by new information or external events” (Beck et al., 2004). David Shapiro (1965) suggested that this information-processing style might be related to social deficits and inability to grasp “’the emotional tone’ of social situations” (Millon, 2000).

So what we have here is a situation in which an attentional deficit leads to a social deficit, at which point the person relies on trying to be perfect so as to avoid social disapproval, rejection and isolation. The solution to this “hardware” type of perfectionism is attention-training and possibly, psychotropic medication.

“There’s a difference between excellence and perfection,” explains Miriam Adderholdt, a psychology instructor at Davidson Community College in Lexington, North Carolina, and author of Perfectionism: What’s Bad About Being Too Good?Excellence involves enjoying what you’re doing, feeling good about what you’ve learned, and developing confidence. Perfection involves feeling bad about a 98 and always finding mistakes no matter how well you’re doing. A child makes all As and one B. All it takes is a parent raising an eyebrow for the child to get the message.

The truly subversive aspect of perfectionism, however, is that it leads people to conceal their mistakes. Unfortunately, that strategy prevents a person from getting crucial feedback—feedback that both confirms the value of mistakes and affirms self-worth—leaving no way to counter the belief that worth hinges on performing perfectly. The desire to conceal mistakes eventually forces people to avoid situations in which they are mistake-prone—often seen in athletes who reach a certain level of performance and then abandon the sport altogether.

Perfectionism is self-defeating in still other ways. The incessant worry about mistakes actually undermines performance. Canadian psychologists Gordon L. Flett and Paul L. Hewitt studied the debilitating effects on athletes of anxiety over perfect performance. They uncovered “the perfection paradox.” “Even though certain sportsrequire athletes to achieve perfect performance outcomes, the tendency to be cognitively preoccupied with the attainment of perfection often undermines performance.” Overconcern about mistakes orients them to failure.

Signs You May Be a Perfectionist

Perfectionism doesn’t have to reach Black Swan levels to wreak havoc on your life and health. Even casual perfectionists (who may not think of themselves as perfectionists at all) can experience the negative side-effects of their personal demand for excellence.

- You believe “I must be perfect or I will be rejected/not approved of/liked.” You make a link between your performance in everything you do and that affecting how people will accept you, which is very important to you.

- If you make a mistake, it’s the end of the world. You catastrophize and exaggerate the importance and impact of the mistakes you might or actually do make. And you may think you won’t survive if you make those mistakes.

- You often procrastinate. Procrastination often is linked to perfectionism. Not only must the task at hand must be done perfectly, otherwise the perfectionist will feel like a failure, but also the conditions must be ideal in advance before action is taken. This is called “having all your ducks in a row,” which is actually an impossibility. So the perfectionist delays taking action, waiting for the ideal conditions or circumstances or overplans.

- You believe the “if…then” proposition—if you can only perform perfectly or be perfect, then you will truly be successful/happy, at peace with yourself.

- There is only one perfect way to do/accomplish things, and everything else is wrong/substandard or a failure.You believe there is only one measure of success—100%.

- You’ve always been eager to please. Perfectionism often starts in childhood. At a young age, we’re told to reach for the stars — parents and teachers encourage their children to become high achievers and give them gold stars for work well done (and in some cases, punishing them for failing to measure up). Perfectionists learn early on to live by the words “I achieve, therefore I am” — and nothing thrills them quite like impressing others (or themselves) with their performance. Unfortunately, chasing those straight A’s — in school, work and life — can lead to a lifetime of frustration and self-doubt.”The reach for perfection can be painful because it is often driven by both a desire to do well and a fear of the consequences of not doing well,” says psychologist Monica Ramirez Basco. “This is the double-edged sword of perfectionism.”

- You know your drive to perfection is hurting you, but you consider it the price you pay for success.The prototypical perfectionist is someone who will go to great (and often unhealthy) lengths to avoid being average or mediocre, and who takes on a “no pain, no gain” mentality in their pursuit of greatness. Although perfectionists aren’t necessarily high achievers, perfectionism is frequently tied to workaholism. “[The perfectionist] acknowledges that his relentless standards are stressful and somewhat unreasonable, but he believes they drive him to levels of excellence and productivity he could never attain otherwise,” famed David Burns writes. The great irony of perfectionism is that while it’s characterized by an intense drive to succeed, it can be the very thing that prevents success. Perfectionism is highly correlated with fear of failure (which is generally not the best motivator) and self-defeating behavior, such as excessive procrastination. Studies have shown that other-oriented perfectionism (a maladaptive form of perfectionism which is motivated by the desire for social approval), is linked with the tendency to put off tasks. Among these other-oriented perfectionists, procrastination stems largely from the anticipation of disapproval from others, according to York University researchers. Adaptive perfectionists, on the other hand, areless prone to procrastination.

- You’re highly critical of others. Being judgmental toward others is a common psychological defense mechanism: we reject in others what we can’t accept in ourselves. And for perfectionists, there can be alotto reject. Perfectionists are highly discriminating, and few are beyond the reach of their critical eye. By being less tough on others, some perfectionists might find that they start easing up on themselves. “Look not to the faults of others, nor to their omissions and commissions,” the Buddha wisely advised. “But rather look to your own acts, to what you have done and left undone.”

- You go big or go home. Many perfectionists struggle with black-and-white thinking — you’re a success one moment and a failure the next, based on your latest accomplishment or failure — and they do things in extremes. If you have perfectionist tendencies, you’ll probably only throw yourself into a new project or task if you know there’s a good chance you can succeed — and if there’s a risk of failure, you’ll likely avoid it altogether. Studies have found perfectionists to be risk-averse, which can inhibit innovation and creativity. For perfectionists, life is an all or nothing game. When a perfectionist sets her mind to something, her powerful drive and ambition can lead her to stop at nothing to accomplish that goal. It’s unsurprising, then, that perfectionists are at high risk for eating disorders.

- You have a hard time opening up to other people. Author and researcher Brene Brown has called perfectionism a “20-ton shield” that we carry around to protect ourselves from getting hurt — but in most cases, perfectionism simply prevents us from truly connecting with others. Because of their intense fear of failure and rejection, perfectionists often have a hard time letting themselves be exposed or vulnerable, according to psychologist Shauna Springer. “It is very hard for a perfectionist to share his or her internal experience with a partner,” Springer writes in Psychology Today. “Perfectionists often feel that they must always be strong and in control of their emotions. A perfectionist may avoid talking about personal fears, inadequacies, insecurities, and disappointments with others, even with those with whom they are closest.”

- You know there’s no use crying over spilt milk… but you do anyway. Whether it’s burning the cookies or being five minutes late for a meeting, the perfection-seeking tend to obsess over every little mistake. This can add up to a whole lot of meltdowns, existential crises, and grown-up temper tantrums. When your main focus is on failure and you’re driven by the desire to avoid it at all costs, even the smallest failure is evidence for a grand thesis of personal failure. “Lacking a deep and consistent source of self-esteem, failures hit especially hard for perfectionists, and may lead to long bouts of depression and withdrawal in some individuals,” writes Springer.

- You take everything personally. Because they take every setback and criticism personally, perfectionists tend to be less resilient than others. Rather than bouncing back from challenges and mistakes, the perfectionist is beaten down by them, taking every misstep as evidence for the truth of their deepest, continually plaguing fear: “I’m not good enough.”

- And you get really defensive when criticized. You might be able to pick out a perfectionist in conversation when they jump to defend themselves at even the slightest hint of a criticism. In an effort to preserve their fragile self-image and the way they appear to others, a perfectionist tries to take control by defending themselves against any threat — even when no defense is needed.

- You’re never quite “there yet.” Because perfection is, of course, an impossible pursuit, perfectionists tend to have the perpetual feeling that they’re not quite there yet. Self-described perfectionist Christina Aguilera told InStyle in 2010 that she focuses on all the things she hasn’t yet accomplished, which gives her a drive to constantly out-do herself. “I am an overachiever and an extreme perfectionist,” Aguilera said. “I would like to do more film and I feel that I still have yet to acquire the type of success that I desire. I’m sure there will definitely be a place that I will be at peace with knowing I’ve accomplished a lot.”

- You take pleasure in someone else’s failure, even though it has nothing to do with you. Misery loves company, and perfectionists — who spend a lot of time and energy thinking and worrying about their own failure — can find relief and even pleasure in others’ failures. For a moment, taking pleasure in someone else’s shortcomings might make you feel better about yourself, but in the long term, it only reinforces the kind of competitive and judgmental thinking that perfectionists thrive on.

- You get secretly nostalgic for your school days. Some people hated school, but you loved it, because success was quantifiable — you had assignments, grades, feedback, and a teacher whose job it was to provide positive feedback and a pat on the back for a job well-done. You might have been a teacher’s pet, or maybe you were voted “Most likely to succeed” in the yearbook. The structure of school and easy equation of “work hard, do well, be rewarded” is a comfort for most perfectionists. In the real world, success is measured differently. Everything is structured differently. And while you might not ever tell anyone, there’s a part of you that misses that world where it was possible to get an A+ and call it a day.

- You have a guilty soul.Underneath it all, perfectionists are often plagued by guilt and shame. Maladaptive perfectionism — a drive to perfection that generally has social roots, and a feeling of pressure to succeed that derives from external, rather than internal, sources — is highly correlated with depression, anxiety, shame and guilt. “Perfectionism is not about striving for excellence or healthy striving,” Brown told Oprah. “It’s… a way of thinking and feeling that says this: ‘If I look perfect, do it perfect, work perfect and live perfect, I can avoid or minimize shame, blame and judgment.”

- You have trouble making decisions.Perfectionists are so worried about making the wrong one that they fail to reach any conclusion. If the person is lucky, someone else will make the decision for them, thereby assuming responsibility for the outcome. More often the decision is made by default.

- You have great difficulty in taking risks, particularly if their personal reputations are on the line.For example, Brent is in a type of job where creativity can be an asset. But coming up with new ideas rather than relying on the tried and true ways of business means making yourself vulnerable to the criticism of others. Brent fears looking like an idiot should an idea he advances fail. And on the occasions when he has gone out on a limb with a new concept he has been overanxious. Brent’s perfectionism illustrates several aspects of the way that many perfectionists think about themselves. There can be low self-confidence, fear of humiliation and rejection, and an inability to attribute success to their own efforts.

How Perfectionism Can Sabotage Work Performance and Lead to Workaholism

Extensive research has found the psychology of perfectionism to be rather complex. Yes, perfectionists strive to produce flawless work, and they also have higher levels of motivation and conscientiousness than non-perfectionists. However, they are also more likely to set inflexible and excessively high standards, to evaluate their behavior overly critically, to hold an all-or-nothing mindset about their performance (“my work is either perfect or a total failure”), and to believe their self-worth is contingent on performing perfectly. Studies have also found that perfectionists have higher levels of stress, burnout, and anxiety. So while certain aspects of perfectionism might be beneficial in the workplace, perfectionistic tendencies can also clearly impair employees at work. Does this make it a weakness?

In the workplace, perfectionism is often marked by low productivity and missed deadlines as people lose time and energy by paying attention to irrelevant details of their tasks, ranging from major projects to mundane daily activities. This can lead to depression, social alienation, and a greater risk of workplace “accidents”.Adderholdt-Elliot (1989) describes five characteristics of perfectionist students and teachers which contribute to underachievement: procrastination, fear of failure, an “all-or-nothing” mindset, paralysed perfectionism, and workaholism.

Researchers looked through four decades of study on perfectionism to answer a morebasic question: Are perfectionists better performers at work? They conducted a meta-analysis of 95 studies, conducted from the 1980s to today, that examined the relationship between perfectionism and factors that impact employees’ effectiveness. These studies included nearly 25,000 working-age individuals.Taken as a whole, the research results indicate that perfectionism is likely not constructive at work. They did find consistent, modestly-sized relationships between perfectionism and variables widely considered to be beneficial for employees and organizations (i.e., motivation and conscientiousness). Yet critically, we found no link between perfectionism and performance. This, coupled with the strong effects of perfectionism on burnout and mental well-being, suggests perfectionism has an overarching detrimental effect for employees and organizations. In other words, if perfectionism is expected to impact employee performance by increased engagement and motivation, then that impact is being offset by opposing forces, like higher depression and anxiety, which have serious consequences beyond just the workplace.

This is not to say that managers should downgrade candidates or employees with high perfectionistic tendencies. Rather, managers should look to harness the benefits while simultaneously acknowledging and mitigating potential consequences. For instance, instead of constantly reminding perfectionists of performance goals (which is likely unnecessary as perfectionists typically hold themselves to the highest possible standards), managers could focus on encouraging perfectionists to set goals for rejuvenating, non-work recovery activities — ones that could help mitigate stress and burnout. Managers can alsoclearly detail their expectations and communicate tolerance for some mistakes.

Taking measures to better manage perfectionists will become a bigger managerial priority. One study of nearly 42,000 young people around the world found that perfectionism has risen over the last 27 years. Striving to be perfect is not overly beneficial for employees and has significant costs for employees and organizations. Instead of encouraging employees to be “perfect,” we might be better off with going for “good enough.”

Being highly motivated and a perfectionist may seem like dream attributes in an employee, but a new study suggests they could also backfire by contributing to workaholism.However, not not all kinds of perfectionism are alike when it comes to turning into a workaholic. What University of Kent researchers termed “self-oriented perfectionism,” which is when a person sets incredibly high standards for his or herself, was linked with workaholism, while “socially prescribed perfectionism,” which is when a person believes he or she needs to meet others’high standards to receive acceptance, was not.

“Our findings also suggest that workaholism in self-oriented perfectionists is driven by those types of motivation characterized by personal importance and ego involvement as well as being motivated by internal rewards and punishment,” study researcher Dr. Joachim Stoeber, who is the head of the School of Psychology at the university, said in a statement.The study was published in the .journal Personality and Individual Differences,All the study participants took tests gauging their perfectionism and work motivation, as well as their workaholism (work addiction).

Researchers found that “employees whose work motivation is characterized by high degrees of congruence and awareness of reasons and goals being in synthesis with the self (identifiedregulation) and/or by high degrees of self-control and ego-involvement and being motivated by internal rewards and punishments (introjected regulation) are more likely to show elevated levels of workaholism compared to employees whose work motivation displays these characteristics to lower degrees,” they wrote in the study.

While working long hours may be nice for your paycheck, it could be doing a serious number on your health. Research has linked working 11 hours or more a day with an increased risk ofdepression, compared with people who work seven to eight hours daily. And while the details are still murky, speculation has risen that a Bank of America intern’s recent death might have had something to do with being overworked.

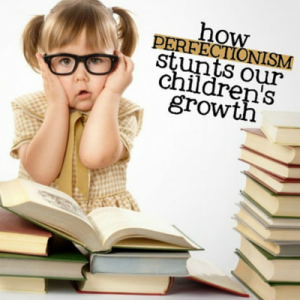

Parenting and Perfectionist Children

When parents and teachers talk about perfectionism—usually in regard to gifted children they invariably ask, “How do we know if a child is a perfectionist and not just working hard?” Sometimes self-worth has become entangled with a narrowly defined sense of achievement (usually good grades and evaluations). A preoccupation with the expectations and judgments (real or imagined) from people around them has made these children their own worst critics. Such characteristics are indicators of perfectionism.

What a perfectionist child stands to lose

The danger of perfectionism is that it disrupts children’s natural curiosity to learn and robs them of the joy they used to feel in the presence of a new discovery, inquiry, or invention. Sadly, these children often become chronic underachievers who are too afraid to take a risk or try anything new.

The following list of behaviors shows how perfectionism creates a loss of this natural, inner drive and motivation to learn. Children who are perfectionists tend to:

- Avoid trying new things for fear of failure;

- Procrastinate and leave work unfinished out of fear it won’t be good enough;

- Focus on mistakes, rather than on what they did well;

- Set unrealistic goals and then condemn themselves when they don’t achieve them;

- Have trouble accepting criticism;

- Find it hard to laugh at themselves;

- Focus on end products, rather than on the process of learning;

- Approach assignments with an inflexibility that insists on one “right” way to do or be;

- Judge themselves severely whenever they get a grade below an “A”;

- Lose their former enthusiasm for learning because of an obsession with what “good work” should look like; and

- Underachieve because of an inability to complete projects considered less than “perfect.”

A number of factors may contribute to perfectionism. Typically, there is a heavy emphasis on performance, both at home and at school. In addition, our society is conditioned to judge one’s level of intelligence according to test scores and grades. When young children feel put on display and praised for their achievements, they naturally conclude that their value as people lies in what they can produce. As time passes and the children continue to excel, they feel less free to strike out in new directions and more pressure to get the grades that will ensure everyone’s approval.Even young children may deny themselves permission to make mistakes and may avoid experiences that could show their weaknesses. Often, they hide the gaps in their knowledge because they think they’ll disappoint the people who admire them.

What Can Help?

The reach for perfection can be painful because it is often driven by both a desire to do well and a fear of the consequences of not doing well. This is the double-edged sword of perfectionism.

It is a good thing to give the best effort, to go the extra mile, and to take pride in one’s performance, whether it is keeping a home looking nice, writing a report, repairing a car, or doing brain surgery. But when you feel as though you keep falling short, never seem to get things just right, never have enough time to do your best, are self-conscious, feel criticized by others, or cannot get others to cooperate in doing the job right the first time, you end up feeling bad.

The problem is not in having high standards or in working hard. Perfectionism becomes a problem when it causes emotional wear and tear or when it keeps you from succeeding or from being happy. The emotional consequences of perfectionism include fear of making mistakes, stressfrom the pressure to perform, and self-consciousness from feeling both self-confidence and self-doubt. It can also include tension, frustration, disappointment, sadness, anger or fear of humiliation. These are common experiences for inwardly focused perfectionists.

The emotional stress caused by the pursuit of perfection and the failure to achieve this goal can evolve into more severe psychological difficulties. Perfectionists are more vulnerable to depression when stressful events occur, particularly those that leave them feeling as though they are not good enough. In many ways, perfectionist beliefs set a person up to be disappointed, given that achieving perfection consistently is impossible. What’s more, perfectionists who have a family history of depression and may therefore be more biologically vulnerable to developing the psychological and physical symptoms of major depression, may be particularly sensitive to events that stimulate their self-doubt and their fear of rejection or humiliation.

Under every perfectionist schema is a hidden fantasy that some really good thing will come from being perfect. For example, “If I do it perfectly, then…I will finally be accepted…I can finally stop worrying…l will get what I have been working toward…I can finally relax.” The flip side of this schema, also subscribed to by perfectionists, is that “If I make a mistake,” there will be a catastrophic outcome (“I will be humiliated ….I am a failure…I am stupid…l am worthless”).

In general, you must treat your perfectionist schemas as hypotheses rather than facts. Maybe you are right or maybe you are wrong. Perhaps they apply in some situations, but not in others (at work, but not at home), or with some people, such as your uptight boss, but not with others, such as your new boyfriend. Rather than stating your schema as a fact, restate it as a suggestion. Gather evidence from your experiences in the past, from your observations from others, or by talking to other people. Do things always happen in a way that your schemas would predict? If not, it is time to try on a new belief.

Other Strategies That Can Help

- Practice Radical Self-Acceptance. Perfectionists tend to be critical of others. It’s a defense mechanism that causes us to reject in others what we can’t accept in ourselves, and the more we pick at our shortcomings, the more we fixate on those of the people around us. These strong feelings come from idealizing the perfect person and life, and it’s a menacing filter we can’t seem to lift off of reality. To kick this habit in the jaw, we must be kind to ourselves. When we like ourselves, even our “flaws” and “imperfections,” we’re much less likely to be grumpy pricks who hold everyone under a microscope. So every morning, tell yourself something you love about yourself. Whatever it is that you choose, choose it for the day, and repeat it when you need that boost. Repeat it and believe it, and practicing that radical self-love beats the hell out of the alternative of living a hard-hearted, locked-down, and unforgiving life.

- Create and Trigger Rituals.As perfectionists, we’re afraid of so many things. Starting new projects, making the wrong life decision, choosing a partner—and each of them share this common denominator: fear of failing. It makes us indecisive and reliant on others to guide. To combat such submissive behavior, we have to cultivate the habit of refusing to let fear dictate our every move—a trick I learned from professional athletes. As Twyla Tharp illustrates in The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It For Life: A pro golfer may walk along the fairway chatting with his caddie, his playing partner, a friendly official or scorekeeper, but when he stands behind the ball and takes a deep breath, he has signaled to himself it’s time to concentrate. A basketball player comes to the free-throw line, touches his socks, his shorts, receives the ball, bounces it exactly three times, and then he is ready to rise and shoot, exactly as he’s done a hundred times a day in practice. By making the start of the sequence automatic, they replace doubt and fear with comfort and routine.

- Lower the Stakes.Constantly basking in the glow of anticipation, we put so much pressure on ourselves to have fun—no, the most fun that’s ever been had in the history of fun-having. It’s too much. It’s unreasonable to place those demands on ourselves, and we end up bitterly emerging from events and get-togethers, giving off the impression that we have someplace better to be, with people who are far more interesting. It’s bad form and has the potential to destroy relationships. So, lower the freaking stakes. Notice when you’re pouting or disengaged. Notice when you’re the only one not laughing, or when you’re frantically pressing patterned napkins instead of enjoying your guests and the party you’re hosting. There’s fun to be had, but you have to allow yourself to let it in. Ridding “should” from your vocabulary helps, too.

- Grieve Unrealized Dreams.Few of us end up becoming what we sketched out in crayons when we were five; Whoever we are, it’s unlikely that we’re who we thought we’d be. And perfectionists, in particular, need to come to terms with that. Since we struggle with these notions of not being enough or never amounting to anything, we need to find consistent comfort in our skin and pride in our accomplishments. So keep a list. Write down what you’ve accomplished this week, month, or year, and see your worth come alive on paper.

- Understand Your Own Definition of Perfection.Each time you sit down to complete a new project, ask yourself: “What does being ‘perfect’ mean to me in this situation?” You’ll probably have a few realistic and fair goals wrapped under the perfection umbrella—like making sure your cover letter is free of spelling mistakes and includes targeted messaging for the job you’re applying for. But, your definition of perfection might also include a few sneaky goals that are unattainable or totally out of your control, like “Make the employer like me better than any of the other candidates.” Once you understand what perfect means to you in each individual situation, you can start to evaluate how important each goal is and how much it will actually influence your success (and realize that you may not be able to achieve “perfection” in every aspect—and that’s totally OK).

- Get to Know the People You’re Trying to Be Perfect for. When you’re focused on being perfect, it’s easy to spend all of your time in your own head—figuring out how to make yourself look better in the eyes of your customer, boss, or future employer. But in order to create something really excellent that those people feel connected to, you need to place the emphasis on them. If you’re about to launch a product, for instance, step away from the product itself and dig into the people you’re building that product for. What problems do they need solved? What are their values? What can you build or write that will surprise and delight them? How can you communicate that product, resume, cover letter, or other assignment in a way that will cause them to stop and really listen? Thoseare the things you should be focusing on.

- Explore Ways to Bring More Openness and Vulnerability to Your Work. Brené Brown, a researcher and one of my favorite authors, once wrote, “Imperfections are not inadequacies; they are reminders that we’re all in this together.” Vulnerability may feel uncomfortable, but at the end of the day, learning how to be vulnerable will put you more ahead of the game—in both your life and business—than striving for perfection ever will.

- Break a Perfectionism-Procrastination Connection. When perfectionismand procrastination combine, you can be your own worst enemy. By freeing yourself from this complex process, you can better use your time to accomplish more with less stress.If you dread the thought of performing poorly, and experience anxiety, what you fear is based on what you think of yourself if you fail, or how others may judge you. You see your performances as successes or failures and measures of your personal worth. This contingent-worth anxiety thinking is a form of dichotomous thinking. According to this judgmental process, you are a winner or a loser, worthy or worthless, strong or weak. For example, you expect and demand at least a B+ grade. The goal is reasonable. The expectation is not. You get a B and feel like a failure.

In a perfectionist world of fixed convictions, it is not enough to do well enough; you have to do perfectly well. It’s not enough to have typical performances; they must be exceptional. When attaining perfection becomes a contingency for worth, it is understandable why anxiety is a common consequence.

Perfectionism is a risk factor for performance anxiety and procrastination. You expect a great performance. You have doubts whether you can achieve perfection. You have an urge to diverge and do something less threatening. You wait until you can be perfect. This is an example of a perfectionism-driven procrastination.

There are at least seven operations involved in this perfectionism-procrastination process. (1) You hold to lofty standards. (2) You have no guarantee you’ll do well enough. (3) Less than the best is not an option. (4) As you think of not doing well enough, you feel uncomfortable. (5) You fear the feelings of discomfort. (6) You hide your imperfections from yourself and dodge discomfort by doing something “safer,” such as playing computer games. (7) You repeat this exasperating process until you get off this contingent-worth merry-go-round by working to do better while not demandingperfection from yourself.

A perfectionism-procrastination combination contributes to what Rockefeller University professor Bruce McEwen describes as an allostatic load. This is a wearing and tearing of the body due to stress. If you hear your inner voice telling you that if you are not great you are a big nothing, you’ve found an anxiety belief that adds to your allostatic load. Uncoupling yourself from this thinking can help end this perfectionism-related stress.

What parents and teachers can do

As parents and teachers, we want children to live up to their potential. The key, though, is defining “potential.” Striving for excellence shouldn’t be a quest for perfection. “Their potential” means the children’s potential to explore and develop the fullness of their own talents, interests, learning styles, and so on. We know from experience that gifted children, in particular, naturally strive for excellence, and that they need specific guidance in navigating the ups and downs (successes and failures) that accompany their level of accomplishment.

There’s a big difference between wanting children to develop their potential and expecting them to be at the top in everything they attempt. When you’re clear that inner achievement—the development of high-level thinking skills, the expansion of creative imagination, the ability to take risks, and the joy of discovery—is far more important than high grades and awards, you’ll be able to help children combat perfectionism.

Joan Franklin Smutny has written 13 books on gifted children, including Stand Up for Your Gifted Child: How to Make the Most of Kids’ Strengths at Schooland at Home. She is director of The Center for Gifted at National-Louis University in Evanston, Illinois.

At the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium, developmental psychologist Luc Goossens and colleagues have identified two distinct sources of psychological control.

One is the parents’ own perfectionism, an excessive concern with mistakes. Parents approve of their children only when high standards are met. Using covert, indirect techniques—a sigh, a strategic silence, the raised eyebrow—perfectionist parents apply their psychological control on the children, who then become self-critical.

Another source of control is parents’ separation anxiety. The adults are overly attached to their kids and anxious about their growing autonomy; a child’s continued development poses the threat of emotional loss and abandonment to the parent. Such parents guilt-trip their kids, approving of their behavior only when the children remain close and dependent on them. Parents tend to resort to keeping their children dependent when their own adult relationships are less than fulfilling.

Whether stirred by fear of loss or a need for status, parents who employ psychological control focus primarily on their own personal needs, not their children’s developmental needs.

Summary:

The most important distinction that must be made is differentiating between striving for excellence/doing one’s best, which is a worthwhile goal and habit versus being a perfectionist, which can be both harmful to self, others and organizations. Perfectionism is not something you want to wish for or practice.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book:Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.