By Ray Williams

January 2022

There’s a mounting body of research evidence that say women may be better suited to leadership roles in current times, and that they perform better than men.

But the glass ceiling has been still holding them back in the U.S. compared other western countries.

The Glass Ceiling

It has always been assumed by the general public and by past leadership research that men make better leaders than women. How else do you account for the dominance of men in important leadership positions in the U.S.? The stereotypic leader has frequently been described in distinctively male characteristics, whereas characteristics such as compassion, kindness, non-judgment and empathy—associated with women—have been viewed as weaknesses.

In an article I wrote in the Financial Post in May, 2010, entitled “What’s Happened to the Glass Ceiling,” I said, “Call it a glass ceiling, glass wall or a glass floor—there is still a barrier blocking senior women leaders in organizations. High-powered executive and professional women are increasingly opting out of, being bypassed, or otherwise disappearing from the professional workforce. While this exists, true diversity in organizations will not happen.”

There still is considerable gender bias when it comes to considering women as leaders. Harvard’s global online research study, which included over 200,000 participants, showed that 76% of people (men and women) are gender-biased and tend to think of men as better suited for careers and women as better suited as homemakers.

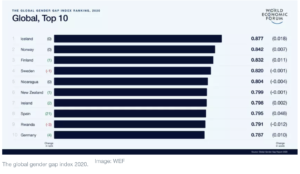

The World Economic Forum’s report called the Global Gender Gap Index, which has been used since 2006 as a tool to capture gender-based disparities, by measuring national gender gaps in economic, political, health and educational metrics on the best countries for women in economic equality terms, place the Scandinavian countries and New Zealand at the top, with Canada rated at 16thand the U.S. at 49th.

The WEF predicted it would take 99.5 years for women to be on an equal footing with men, despite women taking high-profile leadership roles at the European Central Bank and the World Bank, and at the head of several countries including Finland, Germany and New Zealand. In its Gender Gender Gap Index report for 2020, the U.S. is ranked as 53rd in countries in terms of gender equity.

A 2017 Grant Thornton International Business Report found that women now hold 25% of senior management positions globally. The proportion of senior leadership roles held by women has moved by just one percent in 12 months from 24% in 2016 to 25% in 2017 – and four percent in the last five years. Moreover, the percentage of businesses with no women in senior leadership has risen at the same rate – from 33% in 2016 to 34% in 2017 – with no improvement since 2012. In North America 23% of senior roles are held by women; 31% of businesses have no women in senior roles. The US has seen no movement in the past year, with the proportion of senior roles held by women still at 23% and the percentage of businesses without women in top positions remaining at 31%.

The U.S. in particular, is taking steps backwards with respect to gender equality. In the field of law, women are more than 50% of the law students, but less than 25% of law firm partners, federal judges, and law school deans. In 2012, women are expected to earn 63% of master’s degrees and 54% of doctoral and professional degrees, but comprise only 20% of full university professors and only 25% of college presidents. Women comprise only 17% of the U.S. House of Representatives, 16% of the U.S. Senate, 16% of state governors and 24% of all state legislators. Internationally, the U.S. ranks 85th in the world in its share of women in national legislative bodies. Of the largest 100 cities in the U.S., only 9% have female mayors. A recent Catalyst Corporation report showed that women held only 16% of Board of Directors seats at large companies, and more than 25% of Fortune 500 companies had no female executive officers.

Even in the movie industry the picture is the same. In 2015, men directed 95% of the top-grossing films, an increase since 1998. Only 4 women have been nominated for Oscars as best director and only one has won. Eighty-four percent of the 2011 Oscar nominations for screenwriting went to men. Seventy percent of movies starred men, not women. And finally 77% of all Oscars went to men. While the situation has improved in the last two years, parity is still far away.

In the U.S., the recent divisive and acrimonious political campaigns have unearthed attempts to actually move women’s rights and diversity backwards. A record number of state legislative bills and several in Congress are designed to roll back women’s reproductive rights. So too, has proposed substantial pay equity legislation been held up in Congress. An ABC News/Washington Post reported recently that one in four American women have been sexually harassed on the job, yet only 64% of Americans see harassment as a serious workplace problem, down from 88% in 1992. Yet full pay equity would produce a significant stimulus to the consumer-based economy, according to Heidi Hartmann, president of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, who estimates that pay equity would grow the U.S. economy 3-4%, compared to the 1.5% produced by the $800 billion stimulus bailout.

Data show that men win more promotions, more challenging assignments and more access to top leaders than women do. Men are more likely than women to feel confident they are en route to an executive role, and feel more strongly that their employer rewards merit.

Women, meanwhile, perceive a steeper trek to the top. Less than half feel that promotions are awarded fairly or that the best opportunities go to the most-deserving employees. A significant share of women say that gender has been a factor in missed raises and promotions. Even more believe that their gender will make it harder for them to advance in the future—a sentiment most strongly felt by women at senior levels.

These are the conclusions of a major new study of working women conducted by LeanIn.Org and McKinsey & Co. In one of the largest studies to date on this topic, researchers gathered data on promotions, attrition and career outcomes at 132 global companies, and they surveyed 34,000 men and women at those companies on their experiences at work.

The disparity begins at entry level, where men are 30% more likely than women to be promoted to management roles. It continues throughout careers, as men move up the ladder in larger numbers and make up the lion’s share of outside hires. Though their numbers are growing slowly, women hold less than a quarter of senior leadership positions and less than one-fifth of C-suite roles.

Gender Differences in Handling the COVID crisis

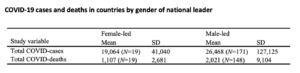

The effectiveness of female leaders in handling the COVID crisis has received a lot of media attention. The findings show that COVID outcomes are systematically better in countries led by women.

On 8 June 2020, New Zealand was declared virus-free and Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern lifted all restrictions except stringent border controls (Graham-McLay 2020). With fewer than 500 confirmed cases and seven deaths from the virus, Taiwan under the presidency of Tsai Ing-Wen is seen to have performed very well. Germany under Angela Merkel has done better than most European countries in the first quarter of the COVID pandemic (Hartl et al. 2020). The performance of these female leaders in the COVID pandemic offers a unique global experiment in national crisis management and has given rise to much media attention. This is a significant shift from the male-dominated view of history within which events are typically considered as determined by the instrumental and causal influence of a small number of “Great Men” (e.g. Keegan 2003).

One explanation for gender-differences in the propensity to lock down early might be found in the literature on attitudes to risk and uncertainty, which suggests that women, even those in leadership roles, appear to be more risk-averse than men (e.g. Croson and Gneezy 2009,. Indeed, in the current crisis, several incidents of risky behaviour by male leaders have been reported. Particularly noteworthy among these are Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro’s dismissal of COVID-19 as “a little flu or a bit of a cold” (Ajzenman et al. 2020) while attending an anti-lockdown protest in April. Similarly, Britain’s Boris Johnson is reported to have said, “I was at a hospital where there were a few coronavirus patients and I shook hands with everybody” (as reported in Lewis 2020). And Donald Trump referred to COVID as “like the flu.”

However, while women leaders were risk averse with regard to lives, they were prepared to take significant risks with their economies by locking down early. Thus, risk aversion may manifest differently in different domains – human life versus economic outcomes – with women leaders being significantly more risk averse in the domain of human life, but more risk taking in the domain of the economy. There is some support for this idea in studies that examine risk taking behaviour when lotteries are framed as losses. Men are found to be more risk averse than women when lotteries are framed as financial losses rather than gains (Schubert et al. 1999, Moore and Eckel 2006). It could well be that the relatively late lockdown decisions by male leaders may reflect male risk aversion to anticipated losses from locking down the economy.

Another explanation of gender differences in response to the pandemic is to be found in the leadership literature, where strong evidence can be found to suggest that men and women differ in their leadership styles. Eagly and Johnson (1990), through a meta-analysis of research that compares male and female leadership styles, find that leadership styles were gender stereotypic, with men likely to lead in a ‘task-oriented’ style and women in an ‘interpersonally oriented’ manner. Consistent with this finding, women tended to adopt a more democratic and participative style. Evidence also suggests that good communications skills are important for women to be chosen as leaders and that this is one of the key attributes in managing a crisis (Lemoine et al. 2016).

Indeed, the decisive and clear communication styles adopted by several female leaders have received much praise in the ongoing crisis ( Henley and Roy 2020, McLean 2020, Taub 2020). Thus, in Norway Prime Minister Erna Solberg spoke direct to children answering their questions, while in New Zealand Prime Minster Ardern was praised for the way in which she communicated and for checking in with her citizens through Facebook Live.

Mariah Levin ,Head of the Forum of Young Global Leaders, World Economic Forum Gwendoline de Ganay,Community Manager for the Americas, Young Global Leaders, World Economic Forum, writing in World Economic Forum described how the COVID pandemic had a better representation by women leaders. In their recent report, “Shaping the Sustainable Organization,” the authors identified the behaviors that generate more inclusive and sustainable organizational outcomes: those that foster “human connections” by championing the values and needs of diverse stakeholders; boost “collective intelligence” through stakeholder engaged decision making; and finally, encourage “accountability at all levels.”

The authors state: “Over the past two years, leaders have faced many unprecedented decisions, and many natural experiments of responsible leadership – that which takes a long-term view with public interest in mind – have unfolded across sectors. Based on observations, research around the unique effectiveness of women’s leadership insights is gaining more traction. In government at national and more local levels, women leaders are associated with fewer deaths and faster action. In companies, women leaders have proven more motivating and communicative during a period of fear and isolation.”

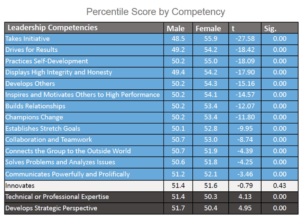

Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman, writing in Harvard Business Review, state: “Between March and June of this year, 454 men and 366 women were assessed on their leadership effectiveness using our Extraordinary Leader 360-degree assessment. Consistent with our pre-pandemic analysis, we found that women were rated significantly more positively than men. Comparing the overall leadership effectiveness ratings of men versus women, once again women were rated as more effective leaders (t-Value 2.926, Sig. 0.004). The gap between men and women in the pandemic is even larger than previously measured, possibly indicating that women tend to perform better in a crisis.”

The authors report that women were rated more positively on 13 of the 19 competencies in our assessment that comprise overall leadership effectiveness. Men were rated more positively on one competency — technical/professional expertise — but the difference was not statistically significant.

In the table below, percentile scores for men and women are displayed sorted by the average rating for women based on data gathered in the first wave of the pandemic.

Other Research on Women in Leadership

Substantial research now exists that says that the general public and workers have more confidence in women in leadership roles and they perform better than men in their roles.

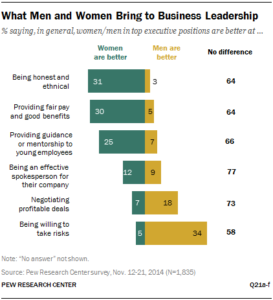

A Pew Center study “Men or Women: Who’s the Better Leader?” concluded “Taken together, the findings of the experimental online survey and the more comprehensive telephone survey present a complex portrait of public attitudes on gender and leadership.

On the one hand, the public asserts that gender discrimination against women and the public’s resistance to change are key factors holding women back from attaining high political office. But at the same time, the public gives higher marks to women than to men on most leadership traits tested in this survey — suggesting that, when it comes to assessments about character, the public’s gender stereotypes are pro-female.”

Kellie A. McElhaney and Sanaz Mobasseri of the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkley, produced a report, “Women Create a Sustainable Future.” Among the conclusions in their research and published in the report, was “companies that explicitly place value on gender diversity perform better in general, and perform better than their peers on the multiple dimensions of corporate sustainability.”

A 2012 Dow Jones study shows that business start-ups are more likely to succeed if they have women on their executive team. And according to the Center for Women’s Business Research, although women own about 40% of the private businesses in the U.S., women make up less than 10% of venture-backed start-ups.

A 2005 Report on Women and Entrepreneurship, the percentage of entrepreneurs who expect growth for the businesses is higher for female entrepreneurs than male entrepreneurs. And according to a separate study by Babson College and the London School of Economics, women led start-ups experienced fewer failures in moving from early to growth–stage companies than men.

Catalyst, the U.S. non-profit company, found that in 2011 a 26% difference in return on invested capital (ROIC) between the top-quartile companies with 19-44% women board representation and the bottom quartile companies with zero women directors. When the McKinsey team asked business executives globally what they believe the most important leadership attributes are for success today, each of the top four—intellectual stimulation, inspiration, participatory decision-making and setting expectations/rewards—were more commonly found among women leaders. McKinsey reported in its Organizational Health Index(OHI) companies with three or more women in top positions scored higher than their peers.

A Pew Center Global Attitudes Project found that 75% of respondents in the U.S. and 80% in Canada believe that women make equally good political leaders, and the numbers were much higher and Europe, Asia and parts of South America. Another Pew Center study, Social and Demographic Survey found women leaders possessed more leadership traits of honesty, intelligence, compassion and creativity than men, whereas men scored higher only in decisiveness.

Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman, authors of The Inspiring Leader: Unlocking the Secrets of How Extraordinary Leaders Activate, writing in the Harvard Business Review Blog Network, argue that in today’s complex demanding world of organizations, women may possess superior leadership capabilities compared to men.

Zenger and Folkman make that contention based on 30 years of research on what constitutes overall leadership effectiveness that comes from 360 evaluations of a leader’s peers, bosses and direct reports and a 2011 survey of over 7,000 leaders from some of the most successful and progressive organizations. They concluded “at every level, more women were rated by their peers, their bosses, their direct reports, and their other associates as better overall leaders than their male counterparts—and the higher the level, the wider the gap grows.”

Specifically, the authors note, “at all levels, women were rated higher in fully 12 or the 16 competencies that go into outstanding leadership. And two of the traits where women outscored men to the highest degree—taking initiative and driving for results—have long been thought of as particularly male strengths.” Men outscored women significantly on only one management competency—the ability to develop a strategic perspective. In fact, at every level, more women were rated by their peers, their bosses, their direct reports, and their other associates as better overall leaders than their male counterparts — and the higher the level, the wider that gap grows.

A new study, led by Professor Øyvind L. Martinsen, head of Leadership and Organisational Behaviour at the BI Norwegian Business School, assessed the personality and characteristics of nearly 3,000 managers and has concluded that women are better suited to leadership than men. In the study, women outperformed men in four of the five categories studied: initiative and clear communication; openness and ability to innovate; sociability and supportiveness; and methodical management and goal-setting.

Personality is almost as significant as intelligence when it comes to our ability to perform work tasks efficiently. “For leaders, personality plays an even bigger role than for many other professions,” according to professors Martinsen and Glasø at the BI Norwegian Business School.

Research has identified five key traits that, overall, provide a good picture of our personality. This is called the five factor model. The five traits in the five factor model are: emotional stability, extraversion (outgoing), openness to new experiences, agreeableness and conscientiousness. The personality traits are measured in degrees, from high to low.

“International research studies show that the most skilled leaders achieve high scores for all five traits,” according to Martinsen and Glasø.

Martinsen and Glasø have analysed data from an extensive leader survey that was was carried out by the Administrative Research Institute (AFF) at the Norwegian School of Economics. The survey measured personality traits in Norwegian managers, work motivation and organisational commitment. More than 2900 leaders provided complete responses to the personality measurements. Of these, more than 900 were women, more than 900 were senior management and nearly 900 came from the public sector.

The survey is based on the recognised theory of human personality, which describes personality as stable response patterns in thinking, emotion and behaviour. Female leaders scored higher than men in four of the five personality traits measured.

“The results indicate that, as regards personality, women are better suited for leadership than their male colleagues when it comes to clarity, innovation, support and targeted meticulousness,” according to the BI researchers.

In their analyses, Martinsen and Glasø compared the personality traits of leaders in the private sector with leaders in the public sector. The results surprised the researchers, and might challenge our perceptions and stereotypes regarding leaders in the public sector.

“Businesses must always seek to attract customers and clients and to increase productivity and profits. Our results indicate that women naturally rank higher, in general, than men in their abilities to innovate and lead with clarity and impact,’” said Professor Martinsen.

“These findings pose a legitimate question about the construction of management hierarchy and the current dispensation of women in these roles.”

Thomas Malone, a management professor at MIT and his colleagues completed research which tried to determine what made a team smarter. He created teams of people aged 18 to 60, had them take IQ tests and then gave them a series of problems to solve. He found that those with the highest IQs did not perform the best, but the teams with the most women did. He reported in the Harvard Business Review, “the standard argument is that diversity is good and you should have both men and women in a group…But so far, the data show, the more women, the better.”

Tony Schwartz, writing in the Harvard Business Review Blog Network describes what women know about leadership than men don’t, arguing “An effective modern leader requires a blend of intellectual qualities—the ability to think analytically, strategically and creatively—and emotional ones, including self-awareness, empathy and humility…I meet far more women with this blend of qualities than I do men.”

He goes on to say “The vast majority of CEOs and senior executives I’ve met over the past decade are men [who] resist introspection, feel more comfortable measuring outcomes than they do managing emotions, and under-appreciate the powerful connection between how people feel and how they perform…For the most part, women, more than men, bring to leadership a more complete range of the qualities modern leaders need, including self-awareness, emotional attunement and authenticity.” Schwartz contends that men overvalue their strengths from an early age, while women tend to undervalue theirs, and that men are often victims of their own egos, and their need to win and use power.

The top scholar on gender and leadership, Dr. Alice Eagly, recently stated that her studies show that women are more likely than men to possess the leadership qualities that are associated with success. That is, women are more transformational than men – they care more about developing their followers, they listen to them and stimulate them to think “outside the box,” they are more inspirational, AND they are more ethical. Dr. Bernard Bass, who developed the current theory of transformational leadership, predicts that in the future women leaders will dominate simply because they are better suited to 21st century leadership/management than are men.

A 2017 Gallup Poll found that when it comes to bosses, Americans no longer prefer a man over a woman. The percentage of U.S. adults preferring a male boss is now 23%, 10 percentage points lower than the last reading in 2014 and 43 points lower than the initial 1953 reading.

In 2014, a study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology analyzed the findings of 99 different studies from 1962–2011 in order to discover nuances within leadership in relation to the gender divide. Predictably, the results suggested that environment played a key role in determining each gender’s general effectiveness in leadership. In male-dominated areas such as military or government, male leaders were viewed to make better leaders than women. Conversely, women were seen as most effective in areas such as social services and education – they also came out on top in the sweeping term “business”.

A survey of more than 600 board directors showed that women are more likely to consider the rights of others and to take a cooperative approach to decision-making. This approach translates into better performance for their companies.

The study, which was published in the International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, was conducted by Chris Bart, professor of strategic management at the DeGroote School of Business at McMaster University, and Gregory McQueen, a McMaster graduate and senior executive associate dean at A.T. Still University’s School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona.

“We’ve known for some time that companies that have more women on their boards have better results,” explains Bart. “Our findings show that having women on the board is no longer just the right thing but also the smart thing to do. Companies with few female directors may actually be shortchanging their investors.”

Bart and McQueen found that male directors, who made up 75% of the survey sample, prefer to make decisions using rules, regulations and traditional ways of doing business or getting along.

Female directors, in contrast, are less constrained by these parameters and are more prepared to rock the boat than their male counterparts.

In addition, women corporate directors are significantly more inclined to make decisions by taking the interests of multiple stakeholders into account in order to arrive at a fair and moral decision. They will also tend to use cooperation, collaboration and consensus-building more often — and more effectively — in order to make sound decisions.

Women seem to be predisposed to be more inquisitive and to see more possible solutions. At the board level where directors are compelled to act in the best interest of the corporation while taking the viewpoints of multiple stakeholders into account, this quality makes them more effective corporate directors, explains McQueen.

Globally, women make up approximately 9% of corporate board memberships. Arguments for gender equality, quotas and legislation have done little to increase female representation in the boardroom, despite evidence showing that their presence has been linked to better organizational performance, higher rates of return, more effective risk management and even lower rates of bankruptcy. Bart’s and McQueen’s finding that women’s higher quality decision-making ability makes them more effective than their male counterparts gives boards a method to deal with the multifaceted social issues and concerns currently confronting corporations.

Boards with high female representation experience a 53% higher return on equity, a 66% higher return on invested capital and a 42% higher return on sales according to a study by Lois Joy and colleagues published by Catalyst.

Having just one female director on the board cuts the risk of bankruptcy by 20% according to Nick Wilson and Ali Altanlar, published in SSRN.

When women directors are appointed, boards adopt new governance practices earlier, such as director training, board evaluations, director succession planning structures according to a study by Val Singh, Savita Kumra & Susan Vinnicombe published in the Journal of Business Ethics.

Women make other board members more civilized and sensitive to other perspectives according to a study by N. Fondas and S. Sassalos, published in Academy of Management Journal.

A study finds less corruption in countries where more women are in government. The new research is the most comprehensive study on this topic and looks at the implications of the presence of women in other occupations as including the shares of women in the labor force, clerical positions, and decision making positions such as the CEOs and other managerial positions.

A greater representation of women in the government is bad news for corruption, according to a new study published in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization by researchers Chandan Jha of Le Moyne College and Sudipta Sarangi of Virginia Tech.

In a cross-country analysis of over 125 countries, this study finds that corruption is lower in countries where a greater share of parliamentarians are women. The study further finds that women’s representation in local politics is important too — the likelihood of having to bribe is lower in regions with a greater representation of women in local-level politics in Europe.

“This research underscores the importance of women empowerment, their presence in leadership roles and their representation in government, said Sarangi, an economics professor and department head at Virginia Tech. “This is especially important in light of the fact that women remain underrepresented in politics in most countries including the United States.”

Less than a quarter of the members of the U.S. Senate are women and only 19 percent of the women in the U.S. House of Representatives are women. It is also noteworthy that the United Stated never had a women head or president.

The authors speculate that women policymakers are able to have an impact on corruption because they choose different policies from men. An extensive body of prior research shows that women politicians choose policies that are more closely related to the welfare of women, children, and family.

Jha and Sarangi’s research is the most comprehensive study on this topic and looks at the implications of the presence of women in other occupations as including the shares of women in the labor force, clerical positions, and decision making positions such as the CEOs and other managerial positions. The study finds that women’s presence in these occupations is not significantly associated with corruption, suggesting that it is the policymaking role through which women are able to have an impact on corruption.

Sometimes it is believed that the relationship between gender and corruption may disappear as women gain similarity in social status. This is presumably because as the status of women improves, they get access to the networks of corruption and at the same time learn the know-how of engaging in corrupt activities. The results of this study, however, indicate otherwise: the relationship between women’s representation in parliament and corruption is stronger for countries where women enjoy a greater equality of status. Once again, this finding further suggests that it’s policymaking through which women are able to impact corruption.

Recent research has shown that trust established by female leaders results in better crisis resolution. This research reflects other recent research that shows that women are better leaders for organizations.

That’s according to a paper published by researchers at Lehigh University and Queen’s University published in the Psychology of Women Quarterly. Their research is the first to examine why and when a female leadership trust advantage emerges for leaders during organizational crises.

Authors on the paper, “A Female Leadership Trust Advantage in Times of Crisis: Under What Conditions?” include Corinne Post, professor of management at Lehigh University ; Iona Latu, lecturer in experimental social psychology at Queen’s University Belfast; and Liuba Belkin, associate professor of management at Lehigh University.

“People trust female leaders more than male leaders in times of crisis, but only under specific conditions,” said co-author Post. “We showed that when a crisis hits an organization, people trust leaders who behave in relational ways, and especially so when the leaders are women and when there is a predictable path out of the crisis.”

The authors found that leaders’ “relational behaviors” serve to strengthen and, on average, are adopted more by women than men. The researchers behaviors which alleviated feelings of threat during a crisis by anticipating and managing the emotions of others; removing or altering a problem to reduce emotional impact; directing attention to something more pleasant; reappraising a situation as more positive; and modulating or suppressing one’s emotional response.

The researchers gave examples such as a product safety concern, consumer data breach, oil spill, corruption allegation or widespread harassment.

“Crises are fraught with relational issues, which, unless handled properly, threaten not only organizational performance but also the allocation of organizational resources and even organizational survival,” the researchers argue, and added “Organizational crises, therefore, require a great deal of relational and emotional work to build or restore trust among those affected and may influence such trusting behaviors as provision of resources to the organization,” including economic resources and investment in the firm, as well as inspiring employee cooperation.”

“We found that this female leadership trust advantage was not just attitudinal, but that — when the consequences of the crisis were foreseeable — people were actually ready to invest much more in the firms led by relational women,” Post said. “Our finding also suggests that, in an organizational crisis, female (relative to male) leaders may generate more goodwill and resources for their organization by using relational behaviors when the crisis fallout is predictable, but may not benefit from the same advantage in crises with uncertain consequences.”

The findings have important implications for leadership and gender research, as well as business professionals. “Identifying what crisis management behaviors enhance trust in female leaders, and under what conditions such trust is enhanced may, for example, help to mitigate the documented higher risk for women (compared to men) of being replaced during drawn-out crises,” the researchers concluded.

Kellie A. McElhaney and Sanaz Mobasseri of the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkley, produced a report, “Women Create a Sustainable Future.” They concluded “companies that explicitly place value on gender diversity perform better in general, and perform better than their peers on the multiple dimensions of corporate sustainability.”

A 2012 Dow Jones study found that business start-ups are more likely to succeed if they had women on their executive team. And according to the Center for Women’s Business Research, although women own about 40% of the private businesses in the U.S., women make up less than 10% of venture-backed start-ups. According to a separate study by Babson College and the London School of Economics, women led start-ups had fewer failures compared to men in moving from early to growth–stage companies.

Catalyst, the U.S. non-profit company, published a study which found a 26% difference in return on invested capital (ROIC) between the top-quartile companies with 19–44% women board representation and the bottom quartile companies with zero women directors.

When McKinsey & Co. researchers asked business executives globally what they believe the most important leadership attributes are for success today, each of the top four — intellectual stimulation, inspiration, participatory decision-making and setting expectations/rewards — were more commonly found among women leaders. McKinsey also reported in its Organizational Health Index(OHI) companies with three or more women in top positions scored higher than their peers.

A Pew Center Global Attitudes study found that 75% of respondents in the U.S. and 80% in Canada believe that women make equally good political leaders. The percentage was even higher in parts of Asia, South America and Europe, according to the study. Another Pew Center study, the Social and Demographic Survey, found women leaders possessed more leadership traits of honesty, intelligence, compassion and creativity than men, whereas men scored higher only in decisiveness.

A sweeping meta-analysis from Florida International University examined 99 data sets from academic research sources—including journal articles, white papers, books and dissertations. The study finds women and men do not differ in their perceived effectiveness as leaders. Assessing feedback on leaders and the extent to which they are judged competent and capable, there is no statistical differences between men and women.

A new study of 423 companies across the US and Canada by McKinsey & Company and Leanin.org finds women are better than men at providing emotional support to employees (19% of men compared with 31% of women) and checking in on the wellbeing of employees (54% compared with 61%). In addition, they are better at helping employees navigate work-life challenges (24% of men compared with 29% of women) and taking action to prevent or manage employee burnout (16% compared with 21%). Women also spend more time contributing to diversity, equity and inclusion efforts (7% of men compared with 11% of women).

A recent study from ResumeLab finds 38% of people prefer to work for a female boss compared with 26% who prefer to work for a man. In addition, 35% of respondents have no preference. When asked whether they are better at leadership, 38% believe women outperform men while 35% believe men are better in leadership roles.

Tomas-Chamorro-Premuzic, in his article “If Women Are Better Leaders, Then Why Are They Not In Charge?” in Forbes states, “Over the past decades, scientific studies have consistently shown that on most of the key traits that make leaders more effective, women tend to outperform men. For example, humility, self-awareness, self-control, moral sensitivity, social skills, emotional intelligence, kindness, a prosocial and moral orientation, are all more likely to be found in women than men.”

He goes on to cite that “Women also outperform men in educational settings, while men score higher than women on dark side personality traits, such as aggression (especially unprovoked), narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism, which account for much of the toxic and destructive behaviors displayed by powerful men who derail.” And this: “All this may explain meta-analytic studies showing that, on average, women are more likely to lead democratically, show transformational leadership, be a role model, listen to others and develop their subordinates’ potential, and score higher on measures of leadership effectiveness.”

In a New York Times article, Sheryl Sandberg and Adam Grant wrote that, “Start-ups led by women are more likely to succeed; innovative firms with more women in top management are more profitable; and companies with more gender diversity have more revenue, customers, market share and profits.” From the same article, Sandberg and Grant reveal that, when male executives speak up, their competency scores rise by 10%. When women executives speak up, their ratings among peers plummet by 14%.

Numerous studies show that boards with more women perform better, with the frequently cited 2015 report by McKinsey & Co underscoring the fact that businesses in the top quartile for gender diversity are 15 per cent more likely to have financial returns above their national industry average.

However, just having a female CEO or a high number of women employees is not enough, says another study, this time of over 22,000 companies across 91 countries. The Peterson-EYstudy reveals that profitable companies include women across top management, who inevitably create a gender-diverse pipeline.

“Women are knocking on the door of leadership at the very moment when their talents are especially well matched with the requirements of the day,” writes David Gergen in the introduction to Enlightened Power: How Women Are Transforming the Practice of Leadership. What are these talents? Once it was thought that leaders should be aggressive and competitive, and that men are naturally more of both. But psychological research has complicated this picture. In lab studies that simulate negotiations, men and women are just about equally assertive and competitive, with slight variations. Men tend to assert themselves in a controlling manner, while women tend to take into account the rights of others, but both styles are equally effective, write the psychologists Alice Eagly and Linda Carli, in their 2007 book, Through the Labyrinth.

A 2008 study attempted to quantify the effect of this more-feminine management style. Researchers at Columbia Business School and the University of Maryland analyzed data on the top 1,500 U.S. companies from 1992 to 2006 to determine the relationship between firm performance and female participation in senior management. Firms that had women in top positions performed better, and this was especially true if the firm pursued what the researchers called an “innovation intensive strategy,” in which, they argued, “creativity and collaboration may be especially important”—an apt description of the future economy.

Women now earn 60 percent of master’s degrees, about half of all law and medical degrees, and 42 percent of all M.B.A.s. Most important, women earn almost 60 percent of all bachelor’s degrees—the minimum requirement, in most cases, for an affluent life. In a stark reversal since the 1970s, men are now more likely than women to hold only a high-school diploma. “One would think that if men were acting in a rational way, they would be getting the education they need to get along out there,” says Tom Mortenson, a senior scholar at the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. “But they are just failing to adapt.”

Policy Initiatives

According to the Catalyst research organization, since 2008, at least 9 countries, including France, Norway, Italy and Spain, have passed legislation requiring some kind of quota requirements for diversity on corporate boards. Other countries, including the U.S., Britain, Australia and Germany have adopted regulations requiring organizations to review board diversity at their annual meetings. Canada at this point lags far behind in these initiatives, with no legislative actions or regulations. In October, 2012, the European Commission proposed a new law that would enforce quotes of 40% for women’s representation on European corporate boards by 2020. The U.S. Federal and State governments have consistently indicated opposition to these ideas.

Joanna Barsh and Lareina Yee, of McKinsey & Company, and authors of a special report for The Wall Street Journal Executive Task Force for Women in the Economy, argue “As the U.S. struggles to sustain historic GDP growth rates, it is critically important to bring more women into the workforce and fully deploy high-skill women to drive productivity improvement.” The authors reviewed over 100 exiting research papers, surveyed 2,500 men and women and interviewed 30 chief diversity officers and experts to determine why there were such low numbers of women leaders in organizations, particularly at the upper levels. Of all the factors that were examined, the authors identified entrenched beliefs as one of the most significant—the prevailing belief that women were not as capable as men to be leaders. Barsh and Yee of McKinsey contend “if companies could raise the number of middle management women who make it to the next level by 25%, it would significantly alter the shape of the leadership talent pipeline.”

Avivah Wittenberg-Cox, writing in the Harvard Business Review Blog Network, commenting on changing corporate culture, “leaders need to tell the majority of men in corporate life that they also need to change, and allow new and different styles of leadership to move in—and up.”

Society and the Economy Has Changed

What if the modern, post-industrial economy is simply more congenial to women than to men? For a long time, evolutionary psychologists have claimed that we are all imprinted with adaptive imperatives from a distant past: men are faster and stronger and hardwired to fight for scarce resources, and that shows up now as a drive to win on Wall Street; women are programmed to find good providers and to care for their offspring, and that is manifested in more- nurturing and more-flexible behavior, ordaining them to domesticity. This kind of thinking frames our sense of the natural order. But what if men and women were fulfilling not biological imperatives but social roles, based on what was more efficient throughout a long era of human history? What if that era has now come to an end? More to the point, what if the economics of the new era are better suited to women?

The post-industrial economy is indifferent to men’s size and strength. The attributes that are most valuable today—social intelligence, open communication, the ability to sit still and focus—are, at a minimum, not predominantly male. In fact, the opposite may be true. Women in poor parts of India are learning English faster than men to meet the demands of new global call centers. Women own more than 40 percent of private businesses in China, where a red Ferrari is the new status symbol for female entrepreneurs. Iceland elected Prime Minister Johanna Sigurdardottir, the world’s first openly lesbian head of state, who campaigned explicitly against the male elite she claimed had destroyed the nation’s banking system, and who vowed to end the “age of testosterone.”

This is the first time that the cohort of Americans ages 30 to 44 has more college-educated women than college-educated men, and the effects are upsetting the traditional Cleaver-family dynamics. In 1970, women contributed 2 to 6 percent of the family income. Now the typical working wife brings home 42.2 percent, and four in 10 mothers—many of them single mothers—are the primary breadwinners in their families. The whole question of whether mothers should work is moot, argues Heather Boushey of the Center for American Progress, “because they just do. This idealized family—he works, she stays home—hardly exists anymore.”

The general public’s—and indeed even leadership experts—views on what constitutes good leaders has not substantially changed, and a 20thcentury stereotype of leaders is persistent, despite research evidence to the contrary. The countries that adapt to the new order the fastest; and recognize the value and need for women in leadership may be the ones that most successfully navigate the balance of the 21stcentury.

In 2008, Sallie Krawcheck was CEO of the Global Wealth Management division at Citigroup. Her company sold clients what Citigroup firmly believed were low-risk investments. After these investments unexpectedly lost most of their value in the market downturn, Krawcheck felt that Citigroup should offer its clients partial refunds.

Her position, at odds with that of her boss and the rest of the management team, led to a lengthy debate within the company that culminated in her dismissal.

In an NPR interview, Krawcheck recalled, “If you’d asked me at that point in time, ‘Sallie, did you get fired because you’re a woman?’ I would have said, ‘What, are you kidding me? Absolutely not.’”

However, as time went on, her answer transitioned to, as she now says, “Well, maybe.”

Sallie Krawcheck’s experience is a high-profile example of what many businesswomen discover early in their careers—often as early as business school: Many of the underlying values and tactics of the business world, while in line with traditionally masculine values, are antithetical to the way women think.

The prevailing message to women in Western society is that if you want to succeed, act more like men. There is an assumption that success means being more aggressive, in control of emotions, and strategic and calculating in your decisions. Getting ahead often means doing whatever it takes, even if you’re acting unethically.

As researchers and teachers of negotiations and leadership with over 40 years of combined experience, we believe that this message is misguided. In fact, women bring unique strengths to the negotiating table—strengths that the prevailing masculine paradigm prevent us from seeing.

Good leadership requires good-faith negotiating that is characterized by courageous and accurate self-disclosures, curious questions, and optimal trade-offs between competing demands. These success-promoting actions are aided by a firm commitment to seeking mutually beneficial solutions; in other words, a moral perspective that values all parties’ interests and not just self-interest.

These findings are consistent with a great deal of prior research that has found women to have higher, more steadfast ethical standards and to act more ethically than men in a variety of behavioral realms.

people and organizational advisory firm, women score higher than men on nearly all emotional intelligence competencies, except emotional self-control, where no gender differences are observed.

According to research by Korn Ferry, data from 55,000 professionals across 90 countries and all levels of management, collected between 2011-2015, using the Emotional and Social Competency Inventory (ESCI), developed and co-owned by Richard E. Boyatzis, Daniel Goleman and Korn Ferry, found that women more effectively employ the emotional and social competencies correlated with effective leadership and management than men.

“Historically in the workplace, there has been a tendency for women to self-evaluate themselves as less competent, while men tend to overrate themselves in their competencies,” said Boyatzis, Ph.D., Distinguished University Professor, Case Western Reserve University. “Research shows, however, that the reality is often the opposite. If more men acted like women in employing their emotional and social competencies, they would be substantially and distinctly more effective in their work.”

In fact, when assessing the competency levels of both men and women across the 12 key areas of emotional and social intelligence, Korn Ferry research found:

- The greatest difference between men and women can be seen in emotional self-awareness, where women are 86% more likely than men to be seen as using the competency consistently (18.4% of women demonstrate the competency consistently compared to just 9.9% of men).

- Women are 45% more likely than men to be seen as demonstrating empathy consistently.

- The smallest margin of difference is seen in positive outlook. When it comes to this emotional intelligence competency, women are only 9% more likely to exhibit the competency consistently than men.

- Other competencies in which women outperform men are coaching & mentoring, influence, inspirational leadership, conflict management, organizational awareness, adaptability, teamwork and achievement orientation.

- Emotional self-control is the only competency in which men and women showed equal performance.

“The data suggests a strong need for more women in the workforce to take on leadership roles,” said Goleman, Co-Director of the Consortium for Research on Emotional Intelligence in Organizations at Rutgers University. “When you factor in the correlation between high emotional intelligence and those leaders who deliver better business results, there is a strong case for gender equity. Organizations must find ways to identify women who score highly on these competencies and empower them.”

Goleman says “As organizations increasingly recognize the importance of providing resources to further nurture and develop female leaders, women who score highly in these emotional and social intelligence competencies will rise to the top. Further, as these competencies underpin highly effective performance, men have a great opportunity to learn from women in the workplace how to best leverage these emotional and social competencies to become more effective leaders.”

Summary:

The picture for genuine gender equality in the world is still not promising, despite gains in recent years. An abundance of research has shown that women not only are as effective as men in leadership positions, but outperform them on multiple measures. Finally, it’s clear that our modern economy and society requires leaders who exhibit such characteristic behaviors such as empathy, compassion, compromise and risk aversion.