How Workaholism is Damaging Our Productivity and Well-Being

By Ray Williams, April 14, 2019

In Japan they call it “karoshi” and in China it is “guolaosi.” As yet there is no word in English for working yourself to death, but as more and more people put in longer hours and suffer more stress there may soon be.

Ronald Reagan was wrong, it seems, when he said: “Hard work never killed anyone,” particularly curious from a man who was known not to work very hard. Death from overwork is not a new phenomenon in Western countries but it is largely unremarked upon. In 1987, the Japanese ministry of labor acknowledged that it had a problem with death from overwork and began to publish statistics on karoshi. In 2001, the numbers reached a record level with 143 workers dying. Now, death-by-overwork lawsuits are common, with the victims’ families demanding compensation payments. Overwork was popularly blamed for the fatal stroke of Prime Minister of Japan Keizō Obuchi in 2000, and in 2013, a Bank of America intern in London died after working for 72 hours straight.

Workaholism Defined

A workaholic is a person who works compulsively. Often at the expense of other pursuits.

While the term generally implies that the person enjoys their work, it can also alternately imply that they simply feel compelled to do it. There is no generally accepted medical definition of such a condition, although some forms of stress, impulse control disorder, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder can be work-related. According to a study published in the Journal of Management, there is a significant difference between being engaged at work and being addicted to it. While the former is characterized by hard work because the worker is passionate about the job, the latter is often motivated by negative feelings like guilt and compulsion.

The word workaholism itself is a portmanteau word composed of work and alcoholic. Its first known appearance, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, came in Canada in the Toronto Daily Star of 5 April 1947, page 6, with a punning allusion to Alcoholics Anonymous: “If you are cursed with an unconquerable craving for work, call Workaholics Synonymous, and a reformed worker will aid you back to happy idleness.”

The term workaholic refers to various types of behavioral patterns, with each having its own valuation. For instance, workaholism is sometimes used by people wishing to express their devotion to one’s career in positive terms. The “work” in question is usually associated with a paying job, but it may also refer to independent pursuits such as sports, music, art and science. However, the term is more often used to refer to a negative behavioral pattern that is popularly characterized by spending an excessive amount of time on working, an inner compulsion to work hard, and a neglect of family and other social relations.

Researchers have found that in many cases, incessant work-related activity continues even after impacting the subject’s relationships and physical health. Causes of it are thought to be anxiety, low self-esteem and intimacy problems. Further, workaholics tend to have an inability to delegate work tasks to others and tend to obtain high scores on personality traits such as neuroticism, perfectionism and conscientiousness.

Clinical psychologist Bryan E. Robinson identifies two axes for workaholics: work initiation and work completion. He associates the behavior of procrastination with both “Savoring Workaholics” (those with low work initiation/low work completion) and “Attention-Deficit Workaholics” (those with high work initiation and low work completion), in contrast to “Bulimic” and “Relentless” workaholics – both of whom have high work completion.

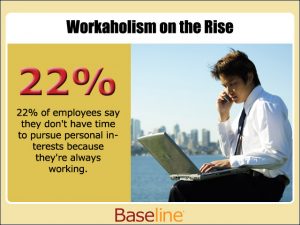

Porter (1996) claims that one in four employed people are workaholics. It has also been claimed that amongst professional groups, the rate of workaholism is high (Doerfler & Kammer, 1986) especially in occupations such as medicine (Killinger, 1992). As a result they work long hours, rarely delegate, expend high effort, and may not necessarily be more productive (Griffiths, 2005a). Inefficiency may also result as a consequence of perfectionist traits (Porter, 1996).

Burke and Matthiesen (2004) note that various authors have conceptualised workaholics in different ways. For instance, some view workaholics as hyper-performers (Korn et al., 1987; Peiperl & Jones, 2001). Others view workaholics as unhappy and obsessive individuals who do not perform well in their jobs (Flowers & Robinson, 2002; Oates, 1971; Porter, 2001; Schaufeli et al., 2006). Others claim workaholism arises when a person prefers to work as a way of stopping the person thinking about their emotional and personal lives (Robinson, 2000) and/or are over concerned with their work and neglect other areas of their lives (Persaud, 2004).

Taris et al. (2008) also note that there is a behavioural component and a psychological component to workaholism. The behavioural component comprises working excessively hard (i.e. a high number of hours per day and/or week), whereas the psychological (dispositional) component comprises being obsessed with work (i.e. working compulsively and being unable to detach from work) (McMillan & O’Driscoll, 2006; Ng et al., 2007; Oates, 1971; Scott et al., 1997; Taris et al., 2004). Spence and Robbins (1992) also assert that this may sometimes be accompanied by other characteristics such as low work enjoyment.

It should also be noted that various researchers differentiate between positive and negative forms of workaholism. For instance, Killinger (1992) views workaholism as both a negative and complex process that eventually affects the person’s ability to function properly. Scott et al. (1997) highlight the workaholics who are totally achievement-oriented and have perfectionist and compulsive-dependent traits. Workaholics appear to have a compulsive drive to gain approval and success, but it can result in impaired judgement and personality breakdowns (Griffiths, 2005a).

Scott et al. (1997) claim there are three central characteristics of workaholics. In short, they (i) spend a great deal of time in work activities; (ii) are preoccupied with work even when they are not working; and (iii) work beyond what is reasonably expected from them to meet their job requirements. Furthermore, they spend more time working because of an inner compulsion, rather than because of any external factors (Ng et al., 2007; Snir & Harpaz, 2004; Taris et al., 2004). Taris et al. (2008) conceptualise workaholism as a syndrome characterized by the number of hours spent on work, and the inability to detach psychologically from work.

Workaholics feel the urge of being busy all the time, to the point that they often perform tasks that are not required or necessary for project completion. As a result, they tend to be inefficient workers, since they focus on being busy, instead of focusing on being productive. In addition, workaholics tend to be less effective than other workers because they have difficulty working as part of a team, trouble delegating or entrusting co-workers, or organizational problems due to taking on too much work at once. Furthermore, workaholics often suffer sleep deprivation, which results in impaired brain and cognitive function.

Is Workaholism an Addiction Like Other Addictions?

Mark Griffiths and his colleagues published a paper in the Journal of Behavioral Addictions examining various myths concerning work addiction. One of the myths we explored was that ‘work addiction is similar to other behavioral addictions’. While work addiction does indeed have many similarities to other behavioral addictions (e.g., gambling, gaming, shopping, sex, etc.), it fundamentally differs from them in a critical way because it is the only behavior that individuals are typically required to do eight hours a day and is an activity that individuals receive gratification from the local environment and/or society more generally for engaging in the activity.

It should be emphasized, Griffiths says, that positive consequences of work addiction are typically short lasting, and in the long run, addiction will take its toll on health (even exercise in excess is physiologically unhealthy in the long run in terms of immune function, cardiovascular health, bone health, and mental health.)

Sam Keen, the author of The Rite of Work: The Economic Man “Men abandoned the power to define happiness for themselves, and… do not attempt to regain it, Keen says. “Today happiness is defined by a set of stereotypes, such as a house, a car, trips, a Rolex instead of a Timex; without these attributes, one cannot be considered successful and, correspondingly, happy.”

Yes, workaholism is an addiction, an obsessive-compulsive disorder, and it’s not the same as working hard or putting in long hours,” says Bryan Robinson, PhD, one of the leading researchers on the disorder and author of Chained to the Desk and other books on workaholism. Workaholic’s obsession with work is all-occupying, which prevents workaholics from maintaining healthy relationships, outside interests, or even take measures to protect their health.

According to psychologist Adam Grant, there is no typical profile, although Baby Boomers are more susceptible to being workaholics than Generation Y workers. Most workaholics are successful. And workaholics are more likely to be managers or executives, more likely to be unhappy about their work/life balance and work on average more than 50 hours per week. They neglect their health to the point of devastating results and ignore their friends and family. They avoid going on vacation so they don’t have to miss work. And even if they do go on vacation, they aren’t fully present because their mind is still on work.

One thing that we do know is that workaholics tend to seek out jobs that allow them to exercise their addiction. The workplace itself does not create the addiction any more than the supermarket creates food addiction, but it does enable it. Workaholics tend to seek high-stress jobs to keep the adrenaline rush going.

Research shows that the seeds of workaholism are often planted in childhood, resulting in low self-esteem that carries into adulthood. Many workaholics are the children of alcoholics or come from some other type of dysfunctional family, and work addiction is an attempt to control a situation that is not controllable. Or they tend to be products of what can be called ‘looking good families’ whose parents tend to be perfectionists and expect unreasonable success from their kids. These children grow up thinking that nothing is ever good enough. Some just throw in the towel, but others say, ‘I’m going to show I’m the best in everything so my parents approve of me.'”

A complex mix of the celebrated 24-hour work culture and attachment to devices makes it even harder to recognize workaholism or the psychiatric disorders it may be linked to. “In order to prevent workaholism [from] developing, there is a need to identify factors involved with this compulsive work pattern – especially since modern technology (i.e., laptops, tablets, smartphones) has blurred the natural lines between home and the workplace,” Schou Andreassen wrote in her study.

Researchers aren’t in agreement about how to define workaholism. Some think that it describes someone who works a lot but doesn’t enjoy what they do. Others argue that a workaholic can also be someone who is really enthusiastic about what they do.

The researchers of the new study defined it as “being overly concerned about work, driven by an uncontrollable work motivation, [and] investing so much time and effort to work that it impairs other important life areas.”

Schou Andreassen found that people who were addicted to work were significantly more likely to meet criteria for ADHD, OCD anxiety and depression. These psychiatric conditions could feed certain people’s drive to work excessively, she hypothesized in her study.

For instance, people with ADHD might have a hard time concentrating with others around them and thus wait until after hours to get most of their work done. People with OCD, on the other hand, tend to obsess over details “to the point of paralysis” — another behavior that may feed workaholism. Anxiety and depression in general also increase the risk of developing addictive behaviors, and the praise people with anxiety or depression get from their work performance could help boost low self esteem, she wrote.

People who scored high on measures of workaholism were also more likely to be young, single, female, highly educated and have higher socioeconomic status than the general group. In terms of the work itself, they were also more likely to be managers, self-employed and people who worked in the private sector.

What is a workaholic, you ask? Well, Barbara Killinger, PhD explained it best, “I define a workaholic as a work-obsessed individual who gradually becomes emotionally crippled and addicted to power and control in a compulsive drive to gain approval and public recognition of success.”

What’s really sad is that workaholism is socially respectable and even encouraged in many fields like law, medicine and on Wall Street. Because we live in such a prestige-obsessed culture few people see it as an addiction. “Workaholism is the best-dressed addiction in the country,” says Bryan E. Robinson, PHD author of Chained to The Desk: A Guidebook For Workaholics, Their Partners, Their Children, And The Clinicians Who Treat Them. It’s such a good looking addiction that rarely anyone seeks help.

It’s laughable that society thinks that workaholism isn’t as bad as alcoholism/drug addiction but it is just as destructive to your body, mental health and family. “A workaholic will die faster than an alcoholic any day,” says Diane Fassel, PhD author of Working Ourselves to Death. By overworking yourself, you’re creating massive levels of adrenaline, which encompasses the whole body and taxes the heart. Workaholics suffer from anxiety, ulcers, fatigue, sleep disturbance and depression.

A Historical Perspective

What has happened to the perennial predictions of a leisure society and escape from long hours of work? In the late 1700’s, Benjamin Franklin predicted we’d work a 4-hour week. In 1933 the U.S. Senate passed a bill for an official 30-hour workweek, which was vetoed by President Roosevelt. In 1965, a U.S. Senate subcommittee predicted a 22-hour workweek by 1985 and a 14-hour work week by 2000.

In his 1930’s essay “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren,” the economist John Maynard Keynes predicted a 15-hour workweek in the 21st century, creating the equivalent of a five-day weekend. “For the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem,” Keynes wrote, “how to occupy the leisure.” In a 1957 article in The New York Times,

The writer Erik Barnouw predicted that, as work became easier, our identity would be defined by our hobbies, or our family life. “The increasingly automatic nature of many jobs, coupled with the shortening work week [leads] an increasing number of workers to look not to work but to leisure for satisfaction, meaning, expression,” he wrote.

The economists of the early 20th Century did not foresee that work might evolve from a means of material production to a means of identity production. They failed to anticipate that, for the poor and middle class, work would remain a necessity, but for the college-educated elite it would morph into a kind of religion, promising identity, transcendence and community.

Atlantic staff writer Eric Thompson contends the American dream–“that mythology that hard work always guarantees upward mobility-has for more than a century made the U.S. obsessed with material success and the exhaustive striving required to earn it.”

Thompson points out that no large country in the world as productive as the U.S. averages more hours of work per year. And the gap between the U.S. and other developed countrees is growing. between 1950 and 2012, he says, of annual hours per employee fell by about 40% in Germany and the Netherlands, but by only 10 % in the U.S. One group has led the widening of the workist gap: rich men. In 1980, the highest-earning men actually worked fewer hours per week than middle- class and low-income men, according to a survey by the Minneapolis Fed. But that’s changed. By 2005, the richest 10 percent of married men had the longest average workweek. In that same time, college-educated men reduced their leisure time more than any other group.

“For many of today’s rich there is no such thing as ‘leisure’; in the classic sense—work is their play,” the economist Robert Frank wrote in The Wall Street Journal. “Building wealth to them is a creative process, and the closest thing they have to fun.” Workism may have started with rich men, but the ethos is spreading—across gender and age. In a 2018 paper on elite universities, researchers found that for women, the most important benefit of attending a selective college isn’t higher wages, bu more hours at the office. “We’ve created this idea that the meaning of life should be found in work,” says Oren Cass, the author of the book The Once and Future Worker. “We tell young people that their work should be their passion. ‘Don’t give up until you find a job that you love!’ we say. ‘You should be changing the world!’ we tell them.”

In his new book, Spending Time: The Most Valuable Resource, Daniel Hamermesh, an economist, examines how work and leisure patterns in America differ from those in the rest of the developed world. In the first half of the 20th century the American working week fell sharply from nearly 60 hours to around 40. By 1979 the average worker in America put in around 38.2 hours a week, similar to the number in Europe.

That is where the figures started to diverge. For a while, the American workweek got longer, reaching 39.4 hours in 2000, before falling back to 38.6 in 2016. The main difference, however, is holidays. In the 1980s Europeans began to take more annual leave but Americans did not. Over the year as a whole, Americans average 34 hours a week, six more than the French and eight more than the Germans.

What explains this gap? Some point to cultural factors but, as Mr Hamermesh points out, it is hard to see why American culture suddenly diverged from that of the rest of the world in the past 40 years. Others point to lower taxes, which raise the value of putting in the extra hour. Yet American taxes were lower than European rates back in the 1960s, when working hours were similar. Another potential explanation is that a decline in trade union membership has weakened American workers’ bargaining power—except that unionisation rates in France and America are not far apart.

A more plausible reason is policy. There is no legal requirement to offer paid holiday in America, whereas France mandates a minimum of 25 days, and Germany, 24. Famously, France also limits the working week to 35 hours. Mr Hamermesh finds similar examples in Asia. In the 1980s and 1990s Japan passed laws reducing the standard working week from 48 hours to 40. Beyond that, workers were entitled to overtime pay. A similar process occurred in South Korea between 2004 and 2008. Employers responded by cutting hours; workers earned less as a result but surveys found they were happier.

In America, by contrast, champions of workers’ rights have recently focused on raising the minimum wage (so far to little avail at the federal level, though some states have enacted more generous wage floors). Wage gains have certainly skewed toward the better-off. The median American worker makes about $20 an hour while the worker at the 95th percentile makes $62. That is a ratio of 3.1. Back in 1979, the ratio was 2.2.

These higher wages do seem to have had an incentive effect. High-paid employees work eight or nine more hours a week than the lowest-paid. In part, this may reflect the low earnings of part-time workers, who have grown as a share of the workforce. Either way, the gap has widened since the late 1970s.

Characteristics of Workaholics

An illustrative story: In an article in the Wall Street Journal, Robert Frank recounts his experiences with wealthy workaholics: “Last week I had dinner with a billionaire in California. During the two hours I was at his house, he took six cellphone calls, sent 18 emails, and thought up two new business ideas…At the end of dinner he took his last sip of wine and said, ‘It’s so nice to be able to have a relaxing dinner at home.’ I laughed. He didn’t get the joke. But another part of the discussion is how the wealthy view work and leisure. For many of today’s rich there is no such thing as “leisure” in the classic sense – work is their play. They don’t sit around the polo field or lounge around the country club all day like Old Money. The new rich are perpetual-motion machines – young, driven and always working on the next project.”

Frank goes on to say, “In short, Thorstein Veblen’s famous “leisure class” has given way to what I call the “workaholic rich.” Even when they’re sitting by the pool at their beach homes in Palm Beach and the Hamptons, they’re tapping away at their laptops and screaming into their cellphones….But this new generation of workaholic wealthy has dramatically changed the classic equation between money and leisure time. As my billionaire friend said after our dinner: ‘I’m the most relaxed when I’m working.’”

In his book, written with Jim Loehr, Tony Schwartz, CEO of The Energy Project, and author of The Power of Full Engagement: Managing Energy, Not Time, recently conducted a poll on the Huffington Post about people’s experience in the workplace. Sixty per cent of 1200 respondents told us they took less than 20 minutes a day for lunch. Twenty per cent took less than 10 minutes. One quarter said they never left their desks at all. That’s consistent with a study by the American Dietetic Association, which found that 75 per cent of office workers eat lunch at their desk at least two to three days a week.

Other Workaholic Characteristics

- Even when people do take vacation days, 30% of people say they worry constantly about work while they are trying to relax.

- 86% of those who admit to workaholic tendencies state that they feel like they must rush through their day in order to get work done effectively.

- More than half of all workaholics end their work-day feeling like they weren’t able to accomplish as much as they could.

- 1 out of 4 people who say they are workaholics will not leave their desk for lunch or to take breaks during the day.

- 75% of workaholics say that they eat lunch at their desk at least 3 times per week.

- A study in the Netherlands showed that 33% of workaholics have regular migraine headaches because of the stresses of their job.

- 3% of workaholics feel physically ill when they are not at work, mimicking withdrawal symptoms that are associated with addictive drugs.

- Compared to 5 years ago, work is a regular part of your evenings and weekends.

- You spend less time with family, friends, community and being engaged in regular activities such as exercise.

- Workaholics eat faster, talk faster, walk faster. They feel like you’re constantly trying to “catch up.”

- They are developing skeletal and muscular problems because of the amount of time they spend sitting or standing, under stress.

- Their focus and concentration is not good, and their productivity is actually declining.

- They think of how they can free up more time to work.

- They work in order to reduce feelings of guilt, anxiety, helplessness or depression.

- They have been told by others to cut down on work but don’t listen to them.

- They deprioritize hobbies, leisure activities, and/or exercise because of their work.

- They are first in the office and last to leave.

- They go to work even when they are sick

- They are too easily accessible.

- They work while on vacation.

- They check their phone repeatedly during their meals.

Workaholism in America

In the Hidden Brain Drain Task Force study in the December, 2006, issue of Harvard Business Review, authors Sylvia Ann Hewlett and Carolyn Buck Luce outlined their conclusions about American’s obsession with work. They state that professionals are working harder than ever and that the 40-hour workweek is a thing of the past. In fact, the 60-hour workweek is commonplace. Hewlett and Luce say 62% of high-earning individuals they studied worked more than 50 hours a week and 35% worked more than 60 hours. Most respondents indicated they worked on average 16 hours a week more than they did five years ago. The study also noted that vacations are shrinking, with 42% reporting they take 10 or fewer vacation days a year, which is less than their entitlement.

Americans “work longer hours, have shorter vacations, get less in unemployment disability, and retirement benefits, and retire later, than people in comparably rich societies,” wrote Samuel P. Huntington in his 2005 book, Who Are We?: The Challenges to America’s National Identity.

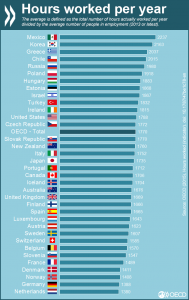

Mexicans work far longer days than anyone else. Germans, on the other hand, clock up the least hours. New data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), whose 35 members include much of the developed world and some developing nations, found the average Mexican spends 2,255 hours at work per year – the equivalent of around 43 hours per week.

Despite enjoying the shortest working hours among OECD member countries, Germany manages to maintain high productivity levels. In fact, the average German worker is reported to be 27% more productive than his or her British counterpart.

The Dutch, French and Danes also work fewer than 1,500 hours per year on average. Just 2% of Danish employees – who enjoy the best work-life balance in the world – put in long hours compared to the OECD average of 13%.

At the same time, Americans are working harder and for longer days. The 40-hour workweek is mostly a thing of the past. Ninety-four percent of professional workers put in 50 or more hours, and nearly half work 65 or above. All workers in most advanced countires have managed to cut down on time on the job by 112 hours over the last 40 years, but Americans are far behind other countries: The French cut down by 491 hours, the Dutch by 425, and Canadians by 215 in the same time period. Workers in Ireland and the Netherlands are also working less. American workers average 137 more hours per year than their Japanese counterparts.

A 2004 report published by the CDC’s Department of Health and Human Services provides a summary of 52 applied psychology studies on the impacts of extended shifts and regular overtime. Across the board, the studies found the impacts were negative—both for employers and employees:

- People who regularly work overtime are less healthy than those who don’t. They’re more likely to gain weight, fall ill, and get injured on the job.

- People are less alert and more likely to make mistakes after the 8th hour of work.

- People who routinely work extended hours and overtime are less productive than those who work eight hours a day and 40 hours a week.

And although a century’s worth of studies have shown that extended shifts and overtime have a variety of negative consequences for both employees and employers, the average number of hours Americans work has been steadily increasing over the last several decades. A 2014 Gallup study found that 50% of full-time workers work more than 40 hours a week.

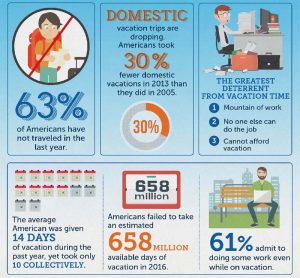

Workaholism and Vacations

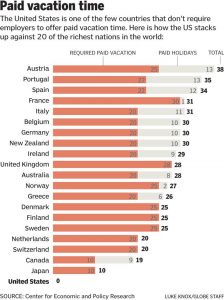

In a report entitled, for the Center for Economic and Policy Research, “No-Vacation Nation,” authors Rebecca Ray and John Schmitt detail the stark contrast between the United States and the 21 other wealthy nations. They provided the following description of vacation time in America:”The United States is the only advanced economy in the world that does not guarantee its workers paid vacation. European countries established legal rights to at least 20 days of paid vacation per year, with legal requirement of 25 and even 30 or more days in some countries. Australia and New Zealand both require employers to grant at least 20 vacation days per year; Canada and Japan mandate at least 10 paid days off. The gap between paid time off in the United States and the rest of the world is even larger if we include legally mandated paid holidays, where the United States offers none, but most of the rest of the world’s rich countries offer between five and 13 paid holidays per year.”

In the absence of government standards, almost one in four Americans have no paid vacation and no paid holidays. According to government survey data, the average worker in the private sector in the United States receives only about nine days of paid vacation and about six paid holidays per year: less than the minimum legal standard set in the rest of world’s rich economies excluding Japan (which guarantees only 10 paid vacation days and requires no paid holidays).

The paid vacation and paid holidays that employers do make available is distributed unequally. According to the same government survey data, lower-wage workers are less likely to have any paid vacation (69 percent) than higher-wage workers are (88 percent). The same is true for part-timers, who are far less likely to have paid vacations (36 percent) than are full-timers (90 percent). The problems of lower-wage and part-time workers are magnified if they are employed in small establishments, where only 70 percent have paid vacations, compared to 86 percent in medium and large establishments.

Even when lower-wage, part-time, and small-business employees do receive paid vacations, they typically receive far fewer paid days off than higher-wage, full-time, employees in larger establishments. For example, the average lower-wage worker (less than $15 per hour) with a vacation benefit received only 10 days of paid vacation per year in 2005, compared to 14 days of paid vacation for higher-wage workers with paid vacations. When we look at workers who receive paid vacations and those who don’t, the vacation gap between lower-wage and higher-wage workers is even larger: only 7 days for lower-wage workers, compared to 13 days for higher-wage workers.

A 2007 report by the World Tourism Organization reported that even Koreans who work hundreds of more hours per year than Americans average nearly twice the number of paid vacation days. On the other side of the scale, people in The Netherlands, which has weathered the recession quite well, work hundreds of hours less per year than Americans, and averaged 45 paid days off at one time.

Kathleen E. Christensen, the founder of the Workplace, Work Force and Working Families program at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and author of the book Workplace Flexibility: Realigning 20th-Century Jobs for a 21st-Century Workforce, states “Many of these countries have strong labor unions and the workers are more protected than in the U.S.” It’s ironic that the country with the largest economy and greatest wealth in the world does not require any vacation time for the workers who create the wealth with their labor. When paid annual and holiday leave is offered, it is less than half of what most other countries receive, and of that almost half of Americans do not use all of their days.

The United States is the only advanced country that doesn’t guarantee that its citizens will get paid vacation time and holidays. European countries, meanwhile, ensure at least 20 days of paid vacation, with some going as high as 30 days, and most rich countries make sure workers get at least six paid holidays. That leaves nearly a quarter of Americans without any access to paid vacation time.

The prospects are equally bleak for workers looking to take time off for other reasons. If they or their family members get sick, there’s no guarantee that they’ll be able to take a paid day off to deal with it, and about 40 percent can’t. Twenty-two other developed countries ensure paid sick leave. In the U.S. when a couple adopts a child or has a newborn, they’re only guaranteed 12 weeks of unpaid time off, and that’s if they qualify—40 percent don’t—unlike virtually every other country that guarantees paid leave.

The U.S. is just one of just 16 countries that doesn’t make sure that workers get at least some time off during the seven-day week. That weekend most of us enjoy come Friday night is not backed up by American policy, but instead is a voluntary employer perk.

But it’s not just policy fueling our overwork; it’s also culture. Professionals, managers, and executives with a smartphone spend 72 hours a week (including the weekend) checking work e-mail. It’s become a nonstop world, especially for professional workers. All employers are offering fewer vacation days and sick days than they used to. And those who are lucky enough to get paid vacation days aren’t using them.

A Glassdoor survey found that three-quarters of American employees don’t use all of their vacation time. The average person takes just half of what she’s allotted. Fifteen percent don’t take any time whatsoever. A different study estimated that we leave about three vacation days unused each year. Even 60 percent of those who took time off in the Glassdoor survey still worked on vacation, many of them because they felt like they couldn’t truly log off.

A study from Ernst & Young found that every ten hours of vacation time taken by an employee boosted her year-end performance rating by 8 percent and lowered turnover. The study showed the average American worker receives 13 vacation days every year, but 34% of workers don’t take a single day of that vacation in any given 12 month period and 34% of American adults don’t take their vacation days. Americans left some $52.4 billion worth of unused vacation time on the table in 2013. That makes ditching vacation both one of the costliest and common ways Americans overwork themselves.

Workaholism and “Busyness”

Connected to the problem of workaholism is “busyness,” which can be defined as a state of having a lot of activity, or of not being idle. You can be overloaded, overwhelmed, snowed, swamped, tied up and stressed. You feel like there is not enough time for all the activities you are either committed to or want to do.

Gallup conducted an August 2017 survey that revealed both professional/executive and white and blue-collar employees worked slightly under 50 hours a week between 47 and 49 hours respectively. Since the 40 hour work week has expanded and peak seasons, special projects, and unique workplace demands have been added – the work week often requires more than 50 hours a week.

U.S.A. Today published a multi-year poll in 2008, to determine how people perceived time and their own busyness. It found that in each consecutive year since 1987, people reported that they are busier than the year before, with 69% responding that they were either “busy,” or “very busy,” with only 8% responding that they were “not very busy.” Not surprisingly, women reported being busier than men, and those between ages 30 to 60 were the busiest. When the respondents were asked what they were sacrificing to their busyness, 56% cited sleep, 52% recreation, 51% hobbies, 44% friends and 30% family. In l987, 50% said they ate at least one family meal everyday; by 2008, that figure had declined to 20%.

Busyness is more than an annoying truth of modern life. It has emerged as a significant health concern, according to Joseph Bienvenu, a psychiatrist and director of the Anxiety Disorders Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital. He sees patients suffering from so much overscheduling that they can’t sleep, think, or make time for important activities like exercise. “Emotional distress due to busyness manifests as difficulty focusing and concentrating, impatience and irritability, trouble getting adequate sleep, and mental and physical fatigue,” he says. “This is a vicious cycle, of course. Emotional distress leads to trouble with sleep and fatigue, and lack of sleep and exercise leads to more distress.”

Busyness and lack of leisure are also being more celebrated in the media. Advertising, often a barometer of social norms, used to feature wealthy people relaxing by the pool or on a yacht. Today, those ads are being replaced with ads featuring busy individuals who work long hours and have very limited leisure time. For example, recall Cadillac’s 2014 Super Bowl commercial featuring a busy and leisure-deprived businessman lampooning those who enjoy long vacations.

Dr. Susan Koven practices internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. In a 2013 Boston Globe column, she wrote: “In the past few years, I’ve observed an epidemic of sorts: patient after patient suffering from the same condition. The symptoms of this condition include fatigue, irritability, insomnia, anxiety, headaches, heartburn, bowel disturbances, back pain, and weight gain. There are no blood tests or X-rays diagnostic of this condition, and yet it’s easy to recognize. The condition is excessive busyness.”

Dr. Michael Marmot, a British epidemiologist, has studied stress and its effects, and found the root causes to be two types of busyness. Though he doesn’t give them official names, he describes the most damaging as busyness without control, which primarily affects the poor. Their economic reality simply does not allow for downtime. They have to work two to three jobs to keep the family afloat. When you add kids to the mix, it becomes overwhelming, and the stress results in legitimate health problems. The other type is busyness with control, which primarily affects the middle and upper classes. Although their economic reality allows for downtime, they don’t take it, but rather fill their time with an increasing variety of activities and consumer products to take care of. This kind of busyness also results in stress and legitimate health problems.

Brigid Schulte, in her 2014 book, Overwhelmed, writes incisively about this trend, “So much do we value busyness, researchers have found a human ‘aversion’ to idleness and a created a need for ‘justifiable busyness.’” Researchers can track the rise of busyness in holiday cards dating back to the 1960s. In holiday cards, Americans used to share news about our lives (the joys and sorrows of the year), but now we’re more likely than ever to mention how busy we are as well.

How busy are you these days? The answer to that question says a lot about your social status, according to new research from McDonough School of Business Assistant Professor of Marketing Neeru Paharia.

“Long hours of work and lack of leisure time have now become a powerful status symbol,” wrote Paharia and her co-authors in their report, “Conspicuous Consumption of Time: When Busyness and Lack of Leisure Time Become a Status Symbol,” published in the Journal of Consumer Research.The busier people say they are or appear to be — whether or not they really are — the more important others perceive them to be, according to the study. In American culture particularly, complaining about being busy, or humblebragging, has become an increasingly widespread phenomenon, Paharia and her colleagues found.

We live in a culture that celebrates being crazy busy: “Western society puts a high value on being busy,” wrote Dr. Christiane Northup, a women’s health expert and New York Times best-selling author. “We are conditioned to believe that being busy equates to being good, worthy, and successful.”

In his article for Harvard Business Review, renowned business leader Greg McKeown calls it “The More Bubble,” and argues society has granted us permission to be proud of being busy.

“This bubble is being enabled by an unholy alliance between three powerful trends: smart phones, social media, and extreme consumerism,” he explained. “The result is not just information overload, but opinion overload. We are more aware than at any time in history of what everyone else is doing and, therefore, what we ‘should’ be doing.”

Time, Productivity and Busyness

Time and productivity have been linked only since the industrial revolution. Humans have always needed to tell time, but the clock, as we know it, wasn’t always the measure. For 10,000 years, humans lived in an agrarian culture and understood time through nature: the seasons, the rise and fall of the sun, and the sow-and-reap rhythm of crops. Eventually humans invented simple devices to mark the hours within a day—sundials, hourglasses, and water clocks, which used the regulated flow of water to measure time.

With the Industrial Revolution, minutes and seconds became a pervasive measurement of time for the common person. The rise of manufacturing regimented time with worker output. Productivity was king, and time translated to money. Today—as the Industrial Revolution cedes to the tech revolution—timekeeping is even more meticulous. We know the exact time in every corner of the world. We leap between time zones and are experiencing for the first time in human history a thing called jet lag, where technology and speed outpace the body’s biological capacity to keep up.

When time became money, our relationship to relaxation also changed. It used to be that the mark of accumulated wealth was leisure—restorative moments away from the toils of labor to enjoy other pursuits. Today, productivity is our top priority. Even the wealthiest among us toil away, packing schedules and squeezing every ounce of value from every second. Bill Gates gave up his golf game in “retirement” to do humanitarian work around the world because, as he told Fortune magazine in 2010, golf “takes up too much time to get any good at it.” (Golf courses around the world are developing nine-hole fast-track courses because people have become too busy to play 18 holes.) As we compete to be productive, busyness is as much a status symbol as anything else.

“There is a distinction between objective time, which you can measure, and subjective time, which is experiential,” explains philosopher Nils F. Schott, at Johns Hopkins University. Schott, who specializes in the philosophy of time, explains that humans enjoy being busy when a task is fulfilling but can feel weighted when a task feels obligatory or when they feel pulled in two directions. There’s a difference between want and should.

This pull can lead to what researchers call toxic time. We worry about what we should be doing for our kids while at work, or we worry about work while out on a date. We may want to exercise, or to stay late at work to complete a particularly fulfilling project, but we feel guilt over what else we should be doing. Time slips away in an unrelenting concern that we should be someplace else doing something more, or that we’re just not able to get to all of the things we hoped to. “We believe that we should be able to do and have everything,” Helzer says. “You’re going to be a great worker, a great partner, a great parent, a great child to your parents, and we’re forever trying to maximize our time.”

This is a big reason for our sense of overwhelm, according to Schulte. “We live under the crazy tyranny of our expectations—that we must be the ideal worker and put in endless hours at work and be the ideal parent and always be available to our children and always be busy and productive, yet doing enough cool stuff and working out and meditating so we’ll look good on our Facebook profile. These over-the-top expectations are actually driving what we think we can and should do in any given day,” she says. “If you are trying to cram a ton of stuff in your day, that creates an atmosphere where you’re breathless and stressed out and you feel powerless.”

The substitution effect: More money makes us more likely to work more

Researchers have uncovered another seemingly irrational aspect to overwork. According to studies, the more money you make the more you’re likely to work. Rather than take advantage of wealth to rest, relax, and focus on personal projects, the top percentage of earners are most likely to put in long hours.

This is because of something called the substitution effect. Basically, when you make more, you view your time at work as worth more than someone with a lower salary.

Here’s an example: Let’s say there’s the choice to go to the office or skip the day and hit the beach. If you make $500 a day, you’ll be more likely to opt for the office. While someone who makes $100 might decide it’s more worth it to head for the beach.

Research on the Negative Impact of Workaholism on Productivity

Working long hours does not necessarily equate to increased productivity, found new research from the B2B marketplace Expert Market. According to their study, the top 10 countries in the study in terms of productivity were:

- Luxembourg – hours worked per week: 31.6; hourly productivity: $60.26

- Norway – hours worked: 27.4; hourly productivity: $47.93

- Australia – hours worked: 32; hourly productivity: $39.30

- Switzerland – hours worked: 30.15; hourly productivity: $39.30

- Netherlands – hours worked: 27.4; hourly productivity: $34.53

- Germany – hours worked: 26.4; hourly productivity: $34.21

- Denmark – hours worked: 27.6; hourly productivity: $31.82

- United States – hours worked: 34.4; hourly productivity: $31.19

- Ireland – hours worked: 35; hourly productivity: $30.47

- Sweden – hours worked: 30.9; hourly productivity: $29.77

So which other countries are prospering despite working less than everyone else? In 2014, an OECD study found Germany to have the shortest working week in the world; a qualification that has done nothing to harm the nation’s productivity, given that it was named the world’s fourth most competitive nation, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2015-16.

In an article in the Harvard Business Review, journalist Sarah Green Carmichael analyzed the published research in an attempt to try to understand why people in many developed countries are now working longer hours than ever before.

She found that not only is there no evidence to suggest that working for longer increases productivity, there’s also a whole slew of research out there that demonstrates the opposite.

Carmichel goes on to say: “Considerable evidence shows that overwork is not just neutral — it hurts us and the companies we work for. Numerous studies by Marianna Virtanen of the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health and her colleagues (as well as other studies) have found that overwork and the resulting stress can lead to all sorts of health problems, including impaired sleep, depression, heavy drinking, diabetes, impaired memory, and heart disease. Of course, those are bad on their own. But they’re also terrible for a company’s bottom line, showing up as absenteeism, turnover, and rising health insurance costs. Even the Scroogiest of employers, who cared nothing for his employees’ well-being, should find strong evidence here that there are real, balance-sheet costs incurred when employees log crazy hours. If your job relies on interpersonal communication, making judgment calls, reading other people’s faces, or managing your own emotional reactions — pretty much all things that the modern office requires — I have more bad news. Researchers have found that overwork (and its accompanying stress and exhaustion) can make all of these things more difficult. Work too hard and you also lose sight of the bigger picture. Research has suggested that as we burn out, we have a greater tendency to get lost in the weeds. This is something business first learned a long time ago. In the 19th century, when organized labor first compelled factory owners to limit workdays to 10 (and then eight) hours, management was surprised to discover that output actually increased – and that expensive mistakes and accidents decreased. This is an experiment that Harvard Business School’s Leslie Perlow and Jessica Porter repeated over a century later with knowledge workers. It still held true. Predictable, required time off (like nights and weekends) actually made teams of consultants more productive.”

A study led by Erin Reid from Boston University found that managers couldn’t tell the difference between consultants who worked 80 hours, and those who just pretended to. “While managers did penalize employees who were transparent about working less, Reid was not able to find any evidence that those employees actually accomplished less, or any sign that the overworking employees accomplished more,” writes Green Carmichael.

One study from Stanford University, however, debunks that belief. In his research, economics professor John Pencavel found that productivity per hour decline sharply when a person works more than 50 hours a week. After 55 hours, productivity drops so much that putting in any more hours would be pointless. And, those who work up to 70 hours a week are only getting the same amount of work done as those who put in the 55 hours.

Former NASA scientists found that people who take vacations experience an 82 percent increase in job performance upon their return, with longer vacations making more of an impact than short ones. Putting in too many hours, on the other hand, does the opposite. More than 60 hours a week will create a small productivity flurry at first, but it’ll start to decline again after three or four weeks. Other studies have found the same initial burst followed, but a worse decline.

Sara Robinson, writing an insightful article in Salon magazine, on the issue of overwork, “Bring Back the 40-hour Work Week,” says “150 years of research proves that long hours at work will kill profits, productivity and employees.” For most of the 20thcentury, the broad consensus among American business leaders was that working people more than 40 hours a week was “stupid, wasteful, dangerous and expensive—and the most telling sign of dangerously incompetent management,” Robinson argues.

Citing the work of Tom Walker of the Work Less Institute’s Prosperity Covenant, “That output does not rise or fall in direct proportion to the number of hours worked is a lesson that seemingly has to be learned by each generation.”

Robinson also cites the work of Evan Robinson, a software engineer who published a paper for the International Developers’ Association in 2005 that argued throughout the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s, and ‘60s research studies conducted by businesses, universities, industry associations and the military supported the shorter (maximum 40 hour) work week. The research indicated that productivity does not rise substantially in extended work days or weeks. Extensive data showed that longer hours of work actually resulted in reduced efficiency and catastrophic accidents, which brought with them substantial liabilities to employers. The research showed that extended hours resulted in reduced brain functioning and physical fatigue, which actually results in loss of productivity.

A Business Roundtable study found that after just eight 60-hour weeks the fall-off in productivity is so marked that the average team would have accomplished as much and been better off if they’d just stuck to a 40-hour week all along. And at 70 or 80 hour weeks, the fall-off happens even faster; at 80 hours, the break-even point is reached in just three weeks. Studies on this subject conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics , U.S. Department of Labor, Proctor and Gamble Company, the National Electrical Contractors Association, and the Mechanical Contractors Association of American produced similar results. All of them showed that continuing scheduled overtime has a strong negative effect on productivity, which increases in magnitude proportionate to the amount and duration of overtime.

So what has accounted for our sudden loss of memory of knowledge about working hours and productivity that pervaded most of the 20thcentury? Robinson points to two factors. The first of these is the development of technology as a cornerstone of our economy, and the culture at the center of that technology—Silicon Valley. The jobs there have attracted a unique breed of brilliant young men and women who fit a particular profile: “single-minded, socially awkward, emotionally detached and blessed (or cursed) with a singular, unique, laser-like focus on some particular area of obsessive interest. For these people, work wasn’t just work; it was their life’s passion and they devoted every waking hour to it, usually to the exclusion of non-work relationships, exercise, sleep, food and sometimes even personal care,” argues Robinson. Overwork and overtime didn’t even appear in their vocabulary.

The new technological corporate ethics and slogans reflected these young overworked employees. For example, for much of its existence Microsoft’s “churn’em and burn’em” philosophy, which translated meant hiring young programmers fresh out of university and working them 70 hours a week or more till they dropped, and then firing them and replacing them with new ones. Fortunately, Microsoft has abandoned this practice.

The second and related development which strengthened the prevalence of overwork was management philosophy and leadership style. For example, management guru Tom Peters’ message of passion for work was translated into working more as the only answer to productivity. And so any aspiring manager or executive worth his salt, who only worked 40 hours a week or less would not be considered promotable talent, or worse, laughed out of the office for appearing to be lazy.

In my article published in Fast Company, I argued that “Research indicates four distinct workaholic “working styles”:The bulimic workaholic feels the job must be done perfectly or not at all. Bulimic workaholics often can’t get started on projects, and then scramble to complete it by deadline, often frantically working to the point of exhaustion — with sloppy results; the relentless workaholic is the adrenaline junkie who often takes on more work than can possibly be done. In an attempt to juggle too many balls, they often work too fast or are too busy for careful, thorough results; the attention-deficit workaholic often starts with fury, but fails to finish projects — often because they lose interest for another project. They often savor the “brainstorming” aspects but get easily bored with the necessary details or follow-through; and the savoring workaholic who is slow, methodical, and overly scrupulous. They often have trouble letting go of projects and don’t work well with others. These are often consummate perfectionists, frequently missing deadlines because it’s not perfect.”

Is there a healthy and acceptable level of work? According to US researcher Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, most modern employees are productive for about four hours a day: the rest is padding and huge amounts of worry. Pang argues that the workday could easily be scaled back without undermining standards of living or prosperity.

There are a few studies that have shown employees are happier, healthier, and more productive when they work less than 40 hours a week.

- During the first two months of 1974, government officials in the United Kingdom limited the workweek to three days in an attempt to save energy. Though people were working two fewer days a week, production only dropped 6%. People worked fewer hours, but they were more productive and less likely to miss work.

- From 2000-2008, the French government limited the maximum working hours per week to 35. In a survey of French employees, more than half said they were happier working reduced hours and more able to achieve a balance between work and life.

Research on the Negative Impact on Health and Well-Being

This overwork shows up in our sleep. Out of five developed peers, four other countries sleep more than us. That has again worsened over the years. In 1942, more than 80 percent of Americans slept seven hours a night or more. Today, 40 percent sleep six hours or less. A lack of sleep makes us poorer workers: People who sleep less than seven hours a night have a much harder time concentrating and getting work done. People who work 11 hours a day or more have a 67% greater chance of suffering from coronary heart disease when compared to those who work a typical 8 hour day. Anyone working 12 or more hours a day is 37% more vulnerable to suffering an injury that is job-related, even in an office environment.

According to a study from workaholism experts at the University of Bergen in Norway, if you find yourself frequently working more than you initially intended, setting aside exercise and leisure for work, and working so much that your health has suffered, you might be more likely to meet the criteria for certain psychiatric disorders. The study found a link between workaholism and disorders like ADHD, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety and depression, and the researchers believe that signs of workaholism may mask these other conditions. If their work is confirmed with additional studies, it could give doctors a way to address disorders masked by workaholism, according to lead researcher Cecilie Schou Andreassen. Alternately, future researchers could find that workaholism may actually cause these psychiatric conditions.

In the 1970s, a mountain of evidence has piled up showing that workaholics display many of the same characteristics as those addicted to drugs or alcohol, such as compulsively engaging in behavior that is ultimately destructive.

Marriages involving a workaholic are twice as likely to end in divorce, a 1999 study found. For those who stay together, the psychological damage can be considerable. Kids of workaholics have been found to experience greater levels of depression and anxiety than the children of alcoholics.

While working long hours may be nice for your paycheck, it could be doing a serious number on your health. Research has linked working 11 hours or more a day with an increased risk of depression, compared with people who work seven to eight hours daily.

A number of studies show that workaholism has been associated with a wide range of health problems, such as insomnia, anxiety, and heart disease. A 2001 study published in the American Journal of Family Therapy found that working too much negatively impacted an employee’s marriage — perhaps not surprising, since if you’re married to your work it can be difficult to be married to anything, or anyone, else — while another also published in the International Journal of Stress Management that same year even found that workaholics can make their co-workers stressed. Their kids don’t do so well either.

Our Beliefs in the Value of Work

For many professionals, work is the center of their social life and friendships. Personal connections, once made exclusively through family, friends and civic organizations, are now made in the workplace. Arlie Hochschild, in the book, The Time Bind, writes that home life can become seriously depleted. She says, as homes and families become starved for time, overworked people avoid going home and choose “more attractive” social venues associated with work. For many, home and family become associated with stress and guilt, while work becomes a haven.

What to conclude? First, it’s obvious, the American workplace is out of step with every other advanced nation regarding the allocation of vacation time, legislated holiday time off, and regulation of working hours. Second, the achievements in productivity may have come at a cost of developing a culture of workaholism.

Woman with digital tablet in office at night

In a society where job dedication is praised, workaholism is an invisible addiction. Work is at the core of much of modern life. If you work excessively you can be both praised in the corporate world, and criticized because of a lack of work-life balance.

“It’s easy to miss the signs,” says Ronald Burke, professor of organizational behavior at the Schulich School of Business, York University, in Toronto. “Work addicts are rewarded, valued members of an organization. But what’s going on in their deepest souls, the signs of pain are not visible.”

There is mixed information on whether there is there a relationship between workaholism and laws governing hours of work. For example in Korea, the 40-hour work week is legally mandated, but most Koreans work far more than that. In general, Asian countries have longer work weeks. All European nations have shorter work weeks (except Britain) than the United States or Canada. However, at least 134 countries have laws setting a maximum length. The U.S. does not. According to the OECD, 85.8% of males and 66.5% of females work more than 40 hours a week. According to the ILO, Americans work 137 more hours a year than Japanese workers, 260 more than British workers and 499 more than the French.

Overachieving professionals today are seen as road warriors, masters of the universe. They work harder, take on endless additional responsibilities and earn a lot more than their counterparts in earlier times, and their numbers are growing. And it is these individuals who bring into clear focus the question of work-life balance.

Tony Schwartz, chief executive of The Energy Project, and co-author of The Power of Full Engagement: Managing Energy, Not Time, Is the Key to High Performance and Personal Renewal, says when it comes to your workday, less is more…but that can be a challenge for many. It’s easy to feel bombarded as you begin your day with incoming emails, meeting notifications and Slack messages that demand your attention.

Although the manifestations of workaholism are at the level of the individual, workaholic behaviour is socially acceptable and even encouraged by major organisations. Consequently, Fassel (1992) views workaholism as much as a ‘system addiction’ as an individual one. Wilson-Schaef and Fassel (1988) have described organisations as potentially addictive in a number of ways. For employees, an organisation can provide the structure and/or the mechanisms and dynamics for both the addictive substance (e.g. adrenalin) and/or the process (i.e. work itself). I Griffiths argues(Griffiths, 2005a) that for someone working too much, it makes little practical difference if they are dependent or addicted. In relation to excessive work, the public understands notions of ‘addiction’ and ‘workaholism’ and these are therefore still very useful constructs for both academic (research) and educational purposes.

The constant chase can make even the most seasoned executives feel overwhelmed. “Busyness is not a means to accomplishment, but an obstacle to it,” writes Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, a Stanford scholar and author of Rest: Why You Get More Done When You Work Less. He argues in his book that when we define ourselves by our “work, dedication, effectiveness and willingness to go the extra mile,” it’s easy to think that doing less and creating more peace in our minds are barriers to success.

Workaholism and Social Media

Since the physical world leaves few traces of achievement, today’s workers turn to social media to make manifest their accomplishments. Many of them spend hours crafting a separate reality of stress-free smiles, postcard vistas, and Edison-lightbulbed working spaces. The social media feed is evidence of the fruits of hard, rewarding labor and the labor itself. Among Millennial workers, it seems, overwork and “burnout” are outwardly celebrated (even if, one suspects, they’re inwardly mourned). In a recent New York Times essay, “Why Are Young People Pretending to Love Work?,” the reporter Erin Griffith pays a visit to the co-working space WeWork, where the pillows urge DO WHAT YOU LOVE, and the neon signs implore workers to HUSTLE HARDER.

These dicta resonate with young workers. As several studies show, Millennials are meaning junkies at work. “Like all employees,” one Gallup survey concluded, “millennials care about their income. But for this generation, a job is about more than a paycheck, it’s about a purpose.”

The problem with this gospel —Your dream job is out there, so never stop hustling— is that it’s a blueprint for spiritual and physical exhaustion. Long hours don’t make anybody more productive or creative; they make people stressed, tired and bitter. But the overwork myths survive “because they justify the extreme wealth created for a small group of elitetechies,” Griffith writes.

Articles in mainstream and social media are replete with exhortations about how you can only be successful if you become an workaholic. For example, read these articles:

· “Why Hard Work is the Key to Success.”

· “5 Reasons You Need to Work Hard to Get Ahead.”

These articles are often accompanied by stories or quotations from famous workaholics like Steve Jobs or Elon Musk who just 24 hours after admitting that he’d almost worked himself to death while making Tesla profitable, Elon Musk tweeted “There are way easier places to work, but nobody ever changed the world on 40 hours a week.” Here’s some other famous examples that are often held up as desirable models of work:

- Steve Jobs left incredibly big shoes for CEO Tim Cook to fill. However, the man got the top job for a reason. He’s always been a workaholic, and Fortune reports that he begins sending emails at 4:30 a.m.A profile in Gawker reveals that he’s the first in the office and the last to leave. He used to hold staff meetings on Sunday night in order to prepare for Monday.

- Mark Cuban writes on his blog that it took an incredible amount of work to benefit from his luck. When starting his first company, the now billionaire routinely stayed up until 2 a.m. reading about new software, and went seven years without a vacation.

- The early days at Amazon were characterized by Jeff Bezos working 12-hourdays, seven days a week, and being up until 3 a.m. to get books shipped.

- A profile in Forbes describes how Nissan and Renault CEO Carlos Ghosn worked more than 65 hours a week, spends 48 hours a month in the air, and flies more than 150,000 miles a year.

- Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer routinely used to put in 130-hour weeks at Google, according to Entrepreneur, a schedule she managed by sleeping under her desk.Even people critical of her management style acknowledge that she “will literally work 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Business Insider’s Nich Carlson reports.

GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt spent 24 years putting in 100-hour weeks.A 2005 Fortune article on Immelt describes him as “the Bionic Manager.” The article highlights his incredible work ethic, saying he worked 100-hour weeks for 24 years

These examples are full of logic flaws, for example, assuming that hard work was the only reason these people were successful, and no other variables can account for the success. And the general public is inundated with the stories of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, full of workholics, some of which have been successful, and many at a cost to their personal lives.

The Myth of Hard Work as the Road to Success

A contributing factor to the problem of workaholism is the prevailing belief in hard work as the route to success, particularly wealth. Notions of hard work are predominantly held by the middle class and poor people and originate from the industrial revolution and Protestant religious tenants, which viewed hard work both as a virtue and magic formula for success. Hard work has never been a belief embraced by the upper class and wealthy. But the growing problem of income inequality, particularly in the U.S., has clearly called into question the validity of the hard work belief.

The United States is the most economically stratified society in the western world. As The Wall Street Journal reported, a recent study found that the top .01% or 14,000 American families hold 22.2% of wealth, and the bottom 90%, or over 133 million families, just 4% of the nation’s wealth. The U.S. Census Bureau and the World Wealth Report 2010 both report increases for the top 5% of households even during the current recession. Based on Internal Revenue Service figures, the richest 1% has tripled their cut of America’s income pie in one generation. The gap between the wealthiest Americans and middle- and working-class Americans has more than tripled in the past three decades, according to a June 25, 2010 report by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. New data shows that the gaps in after-tax income between the richest 1 percent of Americans and the middle and poorest parts of the population in 2007 was the highest it’s been in 80 years, while the share of income going to the middle one-fifth of Americans shrank to its lowest level ever.

The Pew Foundation study, reported in the New York Times, concluded, “The chance that children of the poor or middle class will climb up the income ladder, has not changed significantly over the last three decades.” The Economist‘s special report, Inequality in America, concluded, “The fruits of productivity gains have been skewed towards the highest earners and towards companies whose profits have reached record levels as a share of GDP.” It would not be hard to conclude that even with positive and hopeful attitudes of the middle class and poor people, hard work alone is unlikely to bring the promise of wealth into their lives.

Most people have been told all their lives that the only way to be successful in life is to work harder and longer than the next guy. But the evidence tells us that that’s simply not true. Consider some of the most successful people of our time: Warren Buffett has a tiny office and employs only a handful of people. He works about three hours a day, but he’s one of the richest men in the world. Bill Gates dropped out of college but went on to create one of most influential and successful companies in the world. Neither George W. Bush or Ronald Reagan were fans of hard work, yet they were both elected president of the United States twice.

Maintaining a healthy view of work is harder in a world where social media and mass media are so adamant about externalizing all markers of success. There’s Forbes’ list of this, and Fortune’s list of that; and every Twitter and Facebook and LinkedIn profile is conspicuously marked with the metrics of accomplishment —followers, friends, viewers, retweets—that inject all communication with the features of competition. It may be getting harder each year for purely motivated and sincerely happy workers to opt out of the tournament of labor swirling around them.

American culture worships the pursuit of extreme success will likely produce some of it. But extreme success is a falsifiable god, which rejects the vast majority of its worshippers. Our jobs were never meant to shoulder the burdens of a faith, and they are buckling under the weight. A staggering 87 percent of employees are not engaged at their job, according to Gallup. That number is rising by the year.

Dan Lyon describes the problem of the young tech employee in his book, Lab Rats, in this way: “First, you are lucky to be here. Also, we do not care about you. We offer no job security. This is not a career. You are serving a short-term tour of duty. We provide no training or career development. If possible, we will make you a contractor rather than an actual employee, so that we do not have to provide you with health benefits or a 401(k) plan. We will pay you as little as possible. We do not care about diversity: African Americans and Latinos need not apply. Your job will be stressful. You will work long hours under constant pressure and with no privacy. You will be monitored and surveilled. We will read your email and chat messages, and use data to measure your performance. We do not expect you to last very long. Our goal is to burn you out and churn you out.”

How Work in Organizations Contributes to Workaholism

Many of today’s organizations sabotage flow by setting counter-productive expectations on availability, responsiveness, and meeting attendance, with research by Adobe finding that employees spend an average of six hours per day on email. Another study found that the average employee checks email 74 times a day, while people touch their smartphones 2,617 times a day. Employees are in a constant state of distraction and hyper-responsiveness.

Jason Fried, co-founder of Basecamp and author of It Doesn’t Have to Be Crazy at Work, said on the podcast, Future Squared, that for creative jobs such as programming and writing, people need time to truly think about the work that they’re doing. “If you asked them when the last time they had a chance to really think at work was, most people would tell you they haven’t had a chance to think in quite a long time, which is really unfortunate.”

The typical employee day is characterized by:

- Hour-long meetings, by default, to discuss matters that can usually be handled virtually in one’s own time or via email.

- Unplanned interruptions, helped in no small part by open-plan offices, instant messaging platforms, and the “ding” of desktop and smartphone notifications.

- Unnecessary consensus-seeking for reversible, non-consequential decisions.

- The relentless pursuit of “inbox zero,” a badge of honor in most workplaces, but a symbol of proficiency at putting other people’s goals ahead of one’s own.

- Traveling, often long-distance, to meet people face-to-face, when a phone call would suffice.

- Switching between tasks constantly, and suffering the dreaded cognitive switching penalty as a result, leaving one feeling exhausted with little to show for it.

- Wasting time on a specific task long after most of the value has been delivered.

- Rudimentary and administrative and often unnecessary tasks.

“People waste a lot of time at work,” according to psychologists Adam Grant. “I’d be willing to bet that in most jobs, people would get more done in six focused hours than eight unfocused hours.” Cal Newport, best-selling author of Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World, echoes Grant’s sentiments, saying that “three to four hours of continuous, undisturbed deep work each day is all it takes to see a transformational change in our productivity and our lives.” Fried agreed, saying that he gets into flow for about half the day. “If you don’t get a good four hours of flow to yourself a day, putting more hours in isn’t going to make up for it. It’s just not true that if you stay at the office longer you get more work done.”

The Case for Shorter Week Days and Shorter Work Weeks

Steve Glaveski, writing in the Harvard Business Review, observes, “The internet fundamentally changed the way we live, work, and play, and the nature of work itself has transitioned in large part from algorithmic tasks to heuristic ones that require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity.”

Adam Grant, organizational psychologist and New York Times bestselling author of Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World, says that “the more complex and creative jobs are, the less it makes sense to pay attention to hours at all.” Yet despite all of this, the eight-hour workday still reigns supreme.

Glaveski reports, he “conducted a two-week, six-hour workday experiment with my team at Collective Campus, an innovation accelerator based in Melbourne, Australia. The shorter workday forced the team to prioritize effectively, limit interruptions, and operate at a much more deliberate level for the first few hours of the day. The team maintained, and in some cases increased, its quantity and quality of work, with people reporting an improved mental state, and that they had more time for rest, family, friends, and other endeavors.” He goes on to say “By cultivating a flow-friendly workplace and introducing a shorter workday, you’re setting the scene not only for higher productivity and better outcomes, but for more motivated and less-stressed employees, improved rates of employee acquisition and retention, and more time for all that fun stuff that goes on outside of office walls, otherwise known as life.”

But some businesses shorten their workweeks even more.

For example, employees at eXO Skin Simple work what they call “Swiss hours,” from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Clarke Bowling, the company’s digital marketing manager, said in an NBC News article that the schedule gives employees plenty of time to get their work done without wasting time.

Tower Paddle Boards found similar success after shifting to five-hour workdays, without cutting salaries or benefits. Its employees work from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. each day, eliminating lunch breaks that usually take longer than they should and leave workers in food comas during the afternoon.

Sweden has experimented with six-hour workdays, for both government operations and private companies, with some success.

Earlier this year, a New Zealand company called Perpetual Guardian, which staffs about 240 people, decided to test a 4-day work week for two months in which employees work four 8-hour days but get paid for five. Extensive research was done on this 2-month project in an effort to calculate the effects and changes to work-life balance and productivity.

Well, guess what? The results are in. And they paint a picture of an “unmitigated success.”

As a result of the trial, staff stress levels decreased by 7 percent. The percentage of employees who said they were able to successfully manage their work-life balance increased from 54% to 78%. And overall life satisfaction increased by 5 percentage points.

But wait. What about productivity? Perpetual Guardian reports no decreases despite the shorter work week.

In a 2012 op-ed in the New York Times, software CEO Jason Fried reported that the 32-hour, four-day workweek his company follows from May through October has resulted in an increase in productivity. “Better work gets done in four days than in five,” he wrote. It makes sense: When there’s less time to work, there’s less time to waste. And when you have a compressed workweek, you tend to focus on what’s important. (Like sleep, quality work happens best when uninterrupted.)

In fact, over a third of employees admitted they’re productive for less than 30 hours a week in a recent study conducted with over 3,500 workers. That’s a whole day each week that they’re in work, but not working.

Overall, this low productivity is costing the US a staggering $450 – $550 billion a year. Let’s face it, we’re in the midst of a productivity crisis. Almost 92% of the 3,500 employees spoke told reported that creating better experiences at work will drive them to be more productive in the workplace