By Ray Williams

There are clear signs that North American business schools (ie., MBA programs) may be in trouble. Their difficulties can be defined by:

- Oversupply and declining enrollments.

- The exorbitant cost and value for the cost.

- An increasing irrelevance of business schools in relation to the the significant changes in the global economy and social changes.

- How business education schools must change.

Oversupply and Declining Enrolments

Martin Parker, Professor of Management at the University of Bristol, and author of Shut Down the Business School: What’s Wrong with Management Education, offers this blunt critique of business schools: “Having taught in business schools for 20 years, I have come to believe that the best solution to these problems is to shut down business schools altogether. This is not a typical view among my colleagues. Even so, it is remarkable just how much criticism of business schools over the past decade has come from inside the schools themselves. Many business school professors, particularly in north America, have argued that their institutions have gone horribly astray. B-schools have been corrupted, they say, by deans following the money, teachers giving the punters what they want, researchers pumping out paint-by-numbers papers for journals that no one reads and students expecting a qualification in return for their cash (or, more likely, their parents’ cash). At the end of it all, most business-school graduates won’t become high-level managers anyway, just precarious cubicle drones in anonymous office blocks.”

Parker contends in the business school, both the explicit and hidden curriculums sing the same song. The things taught and the way that they are taught generally mean that the virtues of capitalist market managerialism are told and sold as if there were no other ways of seeing the world. He says, “If we educate our graduates in the inevitability of tooth-and-claw capitalism, it is hardly surprising that we end up with justifications for massive salary payments to people who take huge risks with other people’s money. If we teach that there is nothing else below the bottom line, then ideas about sustainability, diversity, responsibility and so on become mere decoration. The message that management research and teaching often provides is that capitalism is inevitable, and that the financial and legal techniques for running capitalism are a form of science. This combination of ideology and technocracy is what has made the business school into such an effective, and dangerous, institution.”

Managerment exert Steve Denning, writing in Forbes, argues, “As the world undergoes a Fourth Industrial Revolution that is “fundamentally altering the way the way we live, work, and relate to one another—in its scale, scope, and complexity, a transformation … unlike anything humankind has experienced before”—one might imagine that business schools would be hotbeds of innovation and rethinking, with every professor keen to help understand and master this emerging new world.”

Paradoxically, it’s the opposite. For the most part, today’s business schools are busy teaching and researching 20th century management principles and, in effect, leading the parade towards yesterday, Denning says.There is still a large demand for 20th century management. Many managers in large firms have spent decades implementing the doctrines of profit maximization and controlism. They share the same assumptions, goals, values and attitudes. And so their firms continue to be run that way, despite the performance problems it causes. So it is not surprising that these executives seek recruits who have the same mindset. Hence there is still continuing demand for MBA graduates schooled in 20th century thinking. It isn’t obvious that prior management experience plays a large role in becoming a business school professor. The professors usually have no management experience in 20th century management, let alone in firms implementing the new paradigm.

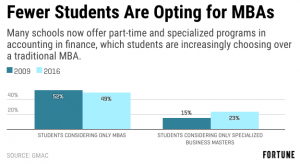

Philip Broughton, writing in the London Times reports there are approximately 500,000 people around the world who now graduate each year with an MBA, 150,000 of those in the US. Applications to full-time M.B.A. programs in the U.S. fell for a third straight year, the latest signal that business schools are struggling to entice young professionals out of a strengthening job market.MBA applications to US business schools are down this year, according to a new survey from the Graduate Management Admission Council. U.S. business schools are seeing a major drop in applications. According to a survey of 1,087 graduate business programs at 363 business schools by the Graduate Management Admission Council, 70 percent of two-year full-time MBA programs in the United States saw a decline in application volume this year. Even the most prestigious institutions were not immune.

According to The Wall Street Journal, Harvard Business School saw a 4.5 percent decline in applications, Stanford’s Graduate School of Business saw a 4.6 percent decline, and Wharton saw a 6.7 percent decline. A number of planned or actual business school closures have occurred at the University of Wisconsin, the University of Iowa, Wake Forest University, Virginia Tech, and Simmons College, and the Thunderbird School of Global Management in Arizona There are various factors in play. Non-MBA graduate business degrees are proliferating; fewer international students are opting for American schools; undergraduate student debt is ballooning; and online courses including massive open online courses (MOOCs) are offering cheaper alternatives to the learning aspect of MBAs, although without the prospect of a lucrative job offer.

The Exorbitant Cost and Value for the Cost

in 1985, writer James Fallows penned what might very well be one of the first attacks against the MBA degree. In a compelling essay entitled “The Case Againt Credentialism” published in The Atlantic, Fallows condemned the rising popularity of the degree.Buried in his criticism, however, was a calculation about the degree’s worth that has been little noticed in more recent years. It was something that Fallows called the “value-added ratio”—how much an MBA degree adds to a person’s salary, compared with how much it costs to obtain.

Fallows noted that the business school community closely follows the ratio. “At Dartmouth’s Amos Tuck School, the nation’s oldest graduate business college, tuition this year is $11,000, and the average starting salary for graduates is around $43,000,” wrote Fallows. “‘That four-to-one ratio has been constant for at least the fifteen or twenty years. I’ve been aware of it,’” he quoted then Tuck Dean Colin Blaydon. Harvard, Fallows also noted, also “reports a four-to-one ratio, down from the heady seven-to-one ratio of 1969, but not so far that Harvard has any trouble filing its admissions quotas.”

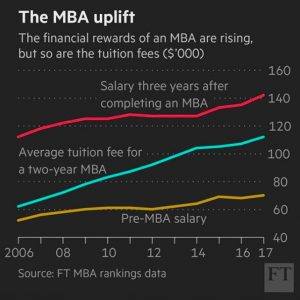

How has that “value-added ratio” changed over these past 33 years? Ever escalating tuition costs have greatly outpaced the relatively miserly rises in MBA starting salaries, causing the results of Fallows’ ratio to fall to shockingly low levels. At Dartmouth Tuck, for example, the average starting salary for last year’s MBA graduates was $127,986, a 198% increase from the $43,000 level of 33 years ago.

And tuition? Last year the annual MBA tuition at Tuck is $68,910, not including “program fees.” That level of tuition alone is 526% above the $11,000 rate in 1985. Not surprisingly then, today’s value-added ratio has plummeted to 1.86-to-1.0 from the four-to-one level of 33 years ago. Tuck is hardly an outlier. At Harvard Business School, the ratio is also down to 1.8, from the four-to-one level in 1985 and far below the almost giddy seven-to-one ratio in 1969 whenbusiness schools graduated far fewer MBAs every year. Harvard annual MBA tuition last year was $72,000 (it is now $73,440), while the average base salary for its graduates last year was $137,293. The ratio? 1.90 to one. The median value-added ratio for a top 25 MBA is now only 1.93 to 1. Fallows concludes that the value-added ratio is an indicator of the declining utility of the MBA.

Among the top full-time MBA programs in the U.S., the best values—by this measure at least—are at four public universities: the University of Washington’s Foster School of Business (2.52), the University of Texa’s McCombs School of Business (2.25), Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business (2.14), and UC-Berkeley’s Haas School of Business (2.10). And those numbers are based on out-of-state tuition. The median for a top 25 program is now 1.93.

There are many reasons why the value added ratio has dramatically shrunk. Global competition has put severe pressure on employers, decompressing pay levels for everyone—not only MBAs. The Great Recession of 2008-2009 actually caused compensation to fall for MBAs and it is only recently begun to recover.

There’s also a supply and demand issue. When Fallows wrote his essay, business schools produced roughly 67,000 new MBAs annually. Today, nearly 200,000 students in the U.S. alone are awarded master’s degrees in business every year since 2010. The MBA, moreover, has become the most popular postgraduate degree in the U.S., according to figures from the U.S. Department of Education. In 2011-2012, the last year for which data is available, 191,571 people graduated from U.S. schools with advanced degrees in business, some 25.4% of all the master’s degrees conferred.The top 20 US MBA programs charge at least $100,000 tuition. The London Business School’s tuition is $130,000 USD.

Here are some other practical limitations for business school graduates:

- Business school won’t help you be a good entrepreneur.

There is no correlation between being a good entrepreneur and going to business school. In fact, according to Saras Sarasvathy, professor at University of Virginia’s Darden Business School, “the most important skill for an entrepreneur is that you know your weakness and you can find people to fill in your gaps. So you pay a bundle to go to school to learn what you don’t knowand how to find people who can do stuff you can’t? Sorry, that doesn’t add up.” The ultimate irony: entrepreneur programs are booming at business schools. - You likely don’t need an MBA for what you want to do.

There are some jobs, very few, where you cannot land if you don’t have an MBA. These are mostly high-level officer-type positions in the Fortune 500. Even then, though, you probably don’t need an MBA. In fact, Forbes reports that CEOs without MBAs bring more value to investors than CEOs who went to business school. - MBAs who are not from a top 10 school don’t increase their earning power.

So if you’re not one of the elite, the degree won’t help you earn more. According to the recruiting firm Challenger & Gray, the degree simply does not separate you from other people in any significant way; it’s too easy to get an MBA from a second-tier school. The cost of the degree is so much more than the combined cost of taking two years off of work and paying for the degree that you are better off taking a job you don’t particularly like and getting a night-school MBA after work hours. - It’s pointless after a certain age.

Let’s say you do get into a top-ten school. Don’t go if you are older than 28. You are too far along in your career to leverage the degree enough to increase your earning power enough to make up for the sticker cost of the degree. In fact, it is so important to get the degree early in your career that Wharton and Harvard have started accepting women earlier than men because the biological clock truncates a woman’s ability to leverage the MBA early enough in their career to make it worth the money. - An MBA over qualifies you for most jobs.

You won’t want entry-level job after you get an MBA, or a job in a low-paying industry because you have to pay back the loans.

Much of Kaufman’s argument rests on a study published eight years ago by Stanford Business School professor Jeffrey Pfeffer of Stanford University and Christina T. Fong of the University of Washington. The pair analyzed 40 years of data and studies and came up with a provocative and startling conclusion: “There is scant evidence that the MBA credential, particularly from non-elite schools, or the grades earned in business courses are related to either salary or the attainment of higher level positions in organizations.”

Nonetheless, Kaufman estimates that all of these firms combined, from Goldman Sachs to McKinsey & Co., probably hire no more than 5,000 to 10,000 MBAs a year out of the more than 200,000 people who are getting MBAs around the world. The other 190,000 to 195,000 are getting MBAs they don’t really need. “For pretty much everyone else, it’s a waste and a very bad investment,” he insists. “”I would probably be the biggest fan of education programs if they cost less and taught more practical skills. You can get a better education faster and cheaper if you do it yourself.” “You should not go to business school,” writes Trunk. “If you want to start a company, you should start a company. And if you want to climb the corporate ladder you should do that. An MBA does not help you with either of those goals.

An increasing irrelevance of business schools in relation to the the significant changes in the global economy and social changes.

For the most part these programs are theory-oriented in nature, and use the traditional tools of conceptual learning—case studies, lectures, films and discussions—relying on the contrast between what managers do and what leaders do. And it appears that the MBA degree and salaries of MBA students are no longer what they used to be.

The problem with many business school leadership programs is that they teach ideas, not real life behaviors, and business school professors are chosen by virtue of their ability to publish detailed research, not having had leadership experience themselves. Understanding something intellectually often has little to do with being able to do it. Adult learners need experiences and coaching to turn concepts into leadership behaviors.

A New York Times article entitled, Is It Time To Retrain B-Schools? has had a massive response. Kelly Holland, the author of the article says among other things, “Critics of business education have many complaints. Some say the schools have become too scientific, too detached from real-world issues. Others say students are taught to come up with hasty solutions to complicated problems. Another group contends that schools give students a limited and distorted view of their role – that they graduate with a focus on maximizing shareholder value and only a limited understanding of ethical and social considerations essential to business leadership. Such shortcomings may have left business school graduates inadequately prepared to make the decisions that, taken together, might have helped mitigate the financial crisis, critics say.”

Henry Mintzberg, a professor of management studies at McGill University in Montreal, also argues that because students spend so much time developing quick responses to packaged versions of business problems, they do not learn enough about real-world experiences. Rakesh Khurana, a professor at Harvard Business School and author of “From Higher Aims to Hired Hands,” a historical analysis of business education, says that business schools never really taught their students that, like doctors and lawyers, they were part of a profession, with professional standards. And in the 1970s, he said, the idea took hold that a company’s stock price was the primary barometer of a leader’s success. This, among other things, changed the business schools’ concept of proper management techniques. Instead of being viewed as long-term economic stewards, he says that managers came to be seen as mainly as the agents of the owners – the shareholders – and responsible for maximizing shareholder wealth. He goes on to say that “we can’t rely on the usual structure of MBA education, which divides the management world into the discrete business functions of marketing, finance, accounting, and so on.”

Khurana offers a scathing critique of business schools in an article in strategy + business. Among other things, he says business schools are “in an incredible race to the bottom”, with around 900 business schools in the US compared to around 180 law schools and around 130 medical schools.

It’s “not even clear what an MBA consists of anymore”. There is a “lack of quality and consistency in the development of general management knowledge”. Business schools have sought academic legitimacy by “aping the arts and sciences faculties,” but social scientists hired into business schools “don’t produce general management knowledge.” And “Very few businesses turn to us. They turn to other sources of knowledge, such as consulting firms, instead.”

Professor Khurana’s main hope seems to be look outside the US: “Today, some of the most innovative business practices are happening outside the United States. These include some of the interesting management practices at technology-services companies like Infosys, the bottom-of-the-pyramid strategies like those that Tata is pursuing with the Nano car, or the rapid innovation of some Chinese companies. We’re living in a multipolar world, at least as far as capitalism is concerned.” One does wonder however whether there aren’t excellent sources of general management knowledge inside the US and Europe, if only business school professors would look.

“In every profession,” writes Joseph Schumpeter in The Economist, “there are people who fail to practice what they preach: dentists with mouths full of rotten teeth, doctors who smoke 40 a day, accountants who forget to file their tax returns. But it is a rare profession where failure to obey its own rules is practically a condition of entry.” Business schools constitute such a profession, writes Schumpeter. “Business schools flout their own rules and ignore their own warnings.”

Warren Bennis and James O’Toole have written how business schools have been on the wrong track for years, claiming among other things that “MBA programs face intense criticism for failing to impart useful skills, failing to prepare leaders, failing to instill norms of ethical behavior.” Rakesh Khurana and Nitin Nohria wrote that schools of management will fail to produce consistently principled, decent leaders until management itself becomes a profession, like medicine or the law which should include a code of conduct.

For universities, business schools have been a means to an end—money. Business schools are less expensive to operate than graduate schools with elaborate labs and research facilities, and alumni tend to be generous with donations. Business education is big business, too. Still, there have been signs that all is not well in business education. A study of cheating among graduate students by Linda Trevino, Ken Butterfield and Donald McCabe, published in 2006 in the journal Academy of Management Learning & Education, found that 56 % of all M.B.A. students cheated regularly—more than in any other discipline. The authors attributed that to “perceived peer behavior.” In other words, students believed everyone else was doing it. No wonder the issue of ethics in corporate America has been seen as important.

McCabe, writing in the Harvard Business Review, contends the prevalence of cheating among MBA students is because of the “get-it-done, dam-the-torpedoes, succeed-at-all costs mentality that many business students bring to he game.” McCabe describes an MBA student mentality of getting the highest GPA possible so that they can get the highest paid jobs in the pharmaceutical, high tech and finance industries.

Michael Jacobs, writing in the Wall Street Journal, argues that there have been three profound failures of sound business practices at the root of the economic crisis that have not been addressed by business schools. The first is the practice of financial incentives as a motivation for leadership, which has morphed into greed. The second is the failure of instituting a financial regulatory system and the absence of any meaningful corporate board responsibility and oversight of CEOs. The third breakdown has been the focus on short-term financial gain for the shareholder at any cost.

Some employers are also questioning the value of an M.B.A. degree. A research project that two Harvard professors released in 2008 found that employers valued graduates’ ability to think through complex business problems, but that something was still lacking. “There is a need to broaden from the analytical focus of M.B.A. programs for more emphasis on skills and a sense of purpose and identity,”said David A. Garvin, a professor of business administration and one of the project’s authors. Indeed, students themselves may welcome an emphasis on character skills and personal development. In surveys that the Aspen Institute regularly conducts, M.B.A. candidates say they actually become less confident during their time in business school that they will be able to resolve ethical quandaries in the workplace.

As Sarah Murray has written in the Financial Times: “While there is growing consensus that focusing on short-term shareholder value is not only bad for society but also leads to poor business results, much MBA teaching remains shaped by the shareholder primacy model.”

There are a number of elements that keep business schools stuck on an obsolete institutional treadmill:

- There is still a large demand for 20th century management. Many managers in large firms have spent decades implementing the doctrines of profit maximization and “controlism.” They share the same assumptions, goals, values and attitudes. And so their firms continue to be run that way, despite the performance problems it causes. So it is not surprising that these executives seek recruits who have the same mindset. Hence there is still continuing demand for MBA graduates schooled in 20th century thinking.

- It isn’t obvious that prior management experience plays a large role in becoming a business school professor. The professors usually have no management experience in 20th century management, let alone in firms implementing the new paradigm.

- It appears that careers in a business school depend more on research than on teaching.

- The accreditation process of business schools guarantees glacial change to core curricula. It takes around five years to have even a small change to the core curriculum accepted by the accreditation process. (One highly-successful dean admits with frustration that 15 years of strenuous effort resulted in only two minor changes in the core curriculum.)

- The widespread use of $200 textbooks suggests financial interests of faculty also prevent change.

- In some cases, business schools also perform a cash-cow function for the rest of the university, as the business school attracts wealthy students from overseas. The risk of losing this revenue stream induces caution in changing a money-making degree.

- In the current setup, what is taught by a business school hardly matters. That’s because business schools mainly perform a “filtering” function (“selection of the sharpest analytic minds”) rather than a teaching function (“what is good management practice for a 21st century firm?”)

- The business school has little need to concern itself with value to the end-users—the students. The inherent learning an MBA provides matters less than the high-salaried job-offers that it leads to. Indeed, the high-cost of an MBA is a feature more than a bug. It’s part of the MBA’s mystique in the marketplace: “Anything that expensive must surely be valuable!”

How did such an unproductive system come about? Many of today’s business school problems date back to 1959, when the Ford Foundation published the Gordon-Howell Report which lambasted the unscientific foundation of business education. In the same year, the Carnegie Foundation also published an analysis with an equally harsh message:

The result? Half a century of business school research that aspired to be “scientific.” The problem is that in a field of human activity that is undergoing dramatic change, findings that can be proven to be universally true by double-blind scientific experiments turn out to be of little practical utility. Research therefore came to be evaluated on the elegance and rigor of the experimental design more than on the utility of the findings. The fact that few, if any, business people ever tried to read, let alone implement, the research was considered irrelevant. Business school research is an enclosed self-referential world—academics writing for other academics. The utility of the entire research enterprise is not a fit subject for discussion.

What went wrong here? Roger Martin argues persuasively that the Ford Foundation made a fundamental conceptual error. It was seeking scientific findings in a subject where science methodology can’t be applied. Here the scientific method would be wholly inappropriate. That part of the world consists of people – of relationships, of interactions, of exchanges. In this part of the world, relationships can be good, bad or indifferent; close, distant or sporadic. They change – they can be other than they currently are. For this part of the world, Aristotle said that the method used to develop our understanding and to shape this world is rhetoric; dialogue between parties that builds understanding that actually shapes and alters this part of the world.

Three Harvard Business School scholars, Srikant M. Datar, David A. Garvin and Patrick G. Cullen, addressed this question in “Rethinking the M.B.A.: Business Education at a Crossroads,” a thought-provoking examination of the curriculums that shape many top investment bankers, consultants and chief executives. After studying the nation’s most prestigious business schools, the authors conclude that an excessive emphasis on quantitative and theoretical analysis has contributed to the making of too many wonky wizards. M.B.A. recipients, according to this book, haven’t learned the importance of social responsibility, common-sense skepticism and respect for the dangers of taking risks with other people’s money.

Put even more bluntly: Business schools played a contributing role in creating the geniuses who brought us the economic meltdown of 2008.“Postcrisis, executives and deans identified a number of gaps in M.B.A. teaching, largely in applied areas,” the authors note. These include risk management, internal governance, behavior of complex systems, regulation and business/government relations and socially responsible leadership. The authors lend credence to critics who “question whether business schools do a good job of alerting students to the imperfections and incompleteness of the models and frameworks they teach.”

Further diminishing the chances that M.B.A. programs will produce wise stewards of capitalism, students are both strikingly disengaged from classes and overly confident about their capabilities, the authors observe. Introspection is rare; avarice, rampant. Several deans reported to the Harvard researchers that the time students spend in, or preparing for, class has declined significantly — at one institution, to 30 hours a week in 2003-4 from about 50 in 1975. The authors add: “Rather than devoting themselves to academics, students were spending increasing amounts of time networking, attending recruiting events, planning club activities and pursuing the best possible job.” One unnamed dean is quoted as mourning: “The focus has shifted from learning to earning.”

How business education schools must change.

So what should business schools focus on? I would argue that business school or executive training programs should focus more on developing individuals’ personal growth with an emphasis on values, emotional intelligenceand ethical behavior in business. The challenge for business schools is how to develop leaders, not managers, and who believe that business has bottom lines beyond shareholder value.

For those companies that continue to be run like the lumbering 20th century mastodons, based on profit maximization and a philosophy of “controlism,” the situation is very different. The examples here are also abundant. “Market-leading companies,” as analyst Alan Murray has written in the Wall Street Journal, “have missed game-changing transformations in industry after industry—computers (mainframes to PCs), telephony (landline to mobile), photography (film to digital), stock markets (floor to online)—not because of ‘bad’ management, but because they followed the dictates of ‘good’ management.”

In effect, the “’good’ management of yesterday” that these firms are practicing—profit maximization and a philosophy of controlism—is obsolete. It was a relatively good fit for much of the 20th century. But then the world changed, and ‘good’ management began to falter. It couldn’t cope with the fast pace and complexity of a customer-driven marketplace. Yet this “‘good management’ of yesterday” is, by and large, what is being taught in today’s business schools. Let’s be clear: the difference between leaders and losers isn’t a matter of access to technology or big dataor artificial intelligence. Both the successful and the unsuccessful firms have access to the same technology, data and AI, which are now largely commodities. Traditionally-managed firms use the same technology and data but typically get meager results. It’s not technology or data or AI that make the difference. The difference lies in the nimbler way these firms deploy technology, data and AI.

Despite individual thought-leaders in business schools, there has been little change in the core curricula of business school teaching as a whole. The disconnect between what is taught and the vast ongoing societal drama under way continues. And it’s difficult to discuss, because it puts in question careers, competencies, job tenure, values, goals, assumptions of the entire business-school world and more.

Not that there haven’t been innovators and leaders in business schools calling for changes such as:

- In 2010, business guru and former business school dean Roger Martin at the Rotman School of Business hailed the advent of customer capitalism over shareholder primacy.

- More recently, two distinguished Harvard Business School professors–Joseph L. Bower and Lynn S. Paine—declared in Harvard Business Review that profit maximization is “the error at the heart of corporate leadership.” It is “flawed in its assumptions, confused as a matter of law, and damaging in practice”, and in effect, “pernicious nonsense.” Yet business schools press ahead with core curricula based on this error, seemingly impervious to issues.

- In 2013, professor Rita McGrath at Columbia Business School challenged the conventional business school theology of sustainable comparative advantage.

- In 2014, professor William Lazonick at the University of Massachusetts Lowell won HBR McKinsey Award winner for the best HBR article of 2014. Lazonick has courageously led the charge in identifying the problems inherent in maximizing shareholder value through massive share buybacks.

- In 2014, professor Clayton Christensen and his colleague Derek van Bever questioned the orthodoxies governing finance and called for a modern-day Martin Luther to articulate the change.

- Business schools also support many technology centers and small programs, such as Jay Goldstein’s program at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering on radical management and Susan George’s program on Agile Management at UC Berkeley Extension.

The paradigm shift in management is no longer a secret: for instance, it’s on the cover of the May-June 2018 issue of Harvard Business Review. It’s the subject of scores of articles in Strategy & Leadership under the bold editorship of Robert Randall. There are also many books written about it, including a recent book co-authored by the managing partner of McKinsey, Talent Wins.

The new management isn’t simply a new training course, or a process, or a methodology or an organizational structure that can be written down in an organizational manual and simply added to the ongoing agenda. It’s a different mindset with counterintuitive ideas that fly in the face of the assumptions of a “good” 20th century manager or the typical business school case:

- Managers can’t tell people what to do.

- Control is enhanced by letting go of control.

- Talent drives strategy.

- Dealing with big issues requires small teams, small tasks, small everything.

- Complex systems are inherently problematic, and must be descaled.

- Companies make more money by not focusing on money.

Internalizing these counter-intuitive ideas and making them part of the culture of an organization—including a business school— doesn’t happen easily or quickly, particularly with people steeped for decades in 20th century thinking.

Interestingly, business itself is beginning to grasp that something is up. Surveys by both Deloitte and McKinsey indicate that over 90% of senior executives want to master new, more flexible business practices, even if less than 10% see their current organization as highly agile.

Meanwhile, business schools keep churning out more standard MBAs, steeped in yesterday’s methodologies—truly excellent executives for the 20th century. Today’s business schools thus resemble medical schools teaching pre-penicillin medicine.

In 2013, Larry Zicklin, a former chairman of the Wall Street investment firm Neuberger Berman, a professor at New York University’s Stern School and a lecturer on ethics at the Wharton school at the University of Pennsylvania, made a revolutionary proposal to fix business schools. Business school teachers, he said, should teach business.

“Academics at business schools now spend a lot of their time doing research for academic journals that is of little practical relevance and that nobody even reads. Zicklin told the Financial Times, “because they are interested in doing it, but it’s also the mechanism by which they get promoted and secure tenure. Because research is an important part of business school rankings, it has created the value system by which academics are rewarded. Research adds so much to the cost of education, especially at business school. But the evidence about research also suggests that most people can’t understand it.”

Although Zicklin’s recommendations have not been widely accepted, there are exceptions. Hult International Business School, for instance, aspires to be relevant to business with a curriculum stressing real-world experience the world and faculty who have management experience.

A group of concerned business academics and business leaders got together and published recommendations for change, which were published as an input for the Drucker Forum 2013:

- A renewed focus on purpose: Business schools should be equipping graduates to be leaders of the 21st Century organization that operates in a complex environment where innovation and responsiveness to customers and society are key.

- Updating the core curriculum: A core curriculum built on shareholder value and efficiency is unsound education for the 21st Century leader. Merely adding more relevant courses on the periphery will be insufficient. Forward-looking business schools should join together in generating textbooks and courses that reflect an updated view of management.

- Changes to the ranking system of business schools: The ranking of business schools by the Financial Times and others should include a criterion that reflects practical relevance, vitality and impact. A new approach to measurement and metrics should reflect society’s complex expectations of business schools.

- Putting “business” back in business schools: Academic recruitment and accreditation processes should be overhauled to reflect today’s complex business world and the need for greater practical relevance.

- Interdisciplinary approaches in research and teaching: The complex problems now facing firms do not fit traditional disciplinary boundaries. They require radical cross-disciplinary thinking that challenges the old assumptions of each discipline. Some business schools are already experimenting with integrative approaches to teaching.

Traditionally, business schools have lacked offerings in the humanities argue Warren Bennis and James O’Toole. That is a serious shortcoming. As teachers of leadership, we doubt that many complex business topics can be understood properly without solid grounding in the humanities. When the hard-nosed behavioral scientist James March taught his famous course at Stanford using War and Peaceand other novels as texts, he emphatically was not teaching a literature course. He was drawing on works of imaginative literature to exemplify and explain the behavior of people in business organizations in a way that was richer and more realistic than any journal article or textbook. Similarly, when executives are given excerpts from the classics of political economy and philosophy in seminars at the Aspen Institute, the intent is not to turn them into experts on Plato and Locke but to illuminate the profound recesses of leadership that scientifically oriented texts either overlook or oversimplify. Bennis and O’Toole go on to argue:

- Naturally, reforming business education means more than adding courses in the humanities. The entire MBA curriculum must be infused with multidisciplinary, practical, and ethical questions and analyses reflecting the complex challenges business leaders face. We are encouraged on this score that the freshly appointed dean of the Marshall School has courageously gone on record as advocating a major rebalancing of our MBA program in order to link hard and soft skills. We certainly do not advocate that business schools, in revising MBA curricula, abandon science. Rather, they should encourage and reward research that illuminates the mysteries and ambiguities of today’s business practices. Oddly, despite B schools’ scientific emphasis, they do little in the areas of contemporary science that probably hold the greatest promise for business education: cognitive science and neuroscience. In those fields, pioneering researchers use magnetic resonance imaging technology to study how the brain behaves while making economic decisions, taking into account such factors as gender differences and the role of trust.

- The problem is not that business schools have embraced scientific rigor but that they have forsaken other forms of knowledge. It isn’t a case of either-or. Not every professor needs to be a switch-hitter, however. In practice, business schools need a diverse faculty populated with professors who, collectively, hold a variety of skills and interests that cover territory as broad and as deep as business itself. As the late Sumantra Ghoshal wrote in a shrewd analysis of the problems with management education today, “The task is not one of delegitimizing existing research approaches, but one of relegitimizing pluralism.”

Summary:

Business schools are in the crosshairs of powerful changes in our economy and society, and like the institutions of higher learning, they will have to adapt or at best they will become less relevant to business in the 21stcentury, or at worst, disappear in their present form.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.

Read my latest book: I Know Myself And Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available in paperback and ebook formats on Amazon and Barnes and Noble world-wide.

U