This article is a 15 minute read.

We’ve got career ladders to climb, businesses to keep afloat, children to raise, classes to attend, appointments to keep, emails to answer, meetings to go to, errands to run, housework to do, and on and on. We’re swamped. We’re pressed for time. We frantically rush from one activity to another. There are so many things that need and take our attention, we don’t even stop to think about what our overloaded lifestyles are doing to us. We are afflicted by the busyness disease.

What is Busyness?

Busyness can be defined as a state of having a lot of activity, or of not being idle. You can be overloaded, overwhelmed, snowed, swamped, tied up and stressed. You feel like there is not enough time for all the activities you are either committed to or want to do.

Gallup conducted an August 2017 survey that revealed both professional/executive and white and blue-collar employees worked slightly under 50 hours a week between 47 and 49 hours respectively. Since the 40 hour work week has expanded and peak seasons, special projects, and unique workplace demands – the work week often requires more than 50 hours a week.

U.S.A. Today published a multi-year poll in 2008, to determine how people perceived time and their own busyness. It found that in each consecutive year since 1987, people reported that they are busier than the year before, with 69% responding that they were either “busy,” or “very busy,” with only 8% responding that they were “not very busy.” Not surprisingly, women reported being busier than men, and those between ages 30 to 60 were the busiest. When the respondents were asked what they were sacrificing to their busyness, 56% cited sleep, 52% recreation, 51% hobbies, 44% friends and 30% family. In l987, 50% said they ate at least one family meal everyday; by 2008, that figure had declined to 20%.

Busyness is more than an annoying truth of modern life. It has emerged as a significant health concern, according to Joseph Bienvenu, a psychiatrist and director of the Anxiety Disorders Clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital. He sees patients suffering from so much overscheduling that they can’t sleep, think, or make time for important activities like exercise. “Emotional distress due to busyness manifests as difficulty focusing and concentrating, impatience and irritability, trouble getting adequate sleep, and mental and physical fatigue,” he says. “This is a vicious cycle, of course. Emotional distress leads to trouble with sleep and fatigue, and lack of sleep and exercise leads to more distress.”

A Harvard Business School survey of 1,000 professionals found that 94% worked at least 50 hours a week, and almost half worked more than 65 hours. Other research shows that the share of college-educated American men regularly working more than 50 hours a week rose from 24% in 1979 to 28% in 2006. According to another survey, 60% of those who use smartphones are connected to work for 13.5 hours or more a day. European labor laws rein in overwork; in the U.S. 40% of managers say they put in more than 60 hours a week.

All this work has left less time for play. Though leisure time has increased overall, a closer look shows that most of the gains took place between the 1960s and the 1980s. Since then economists have noticed a growing “leisure gap”, with the lion’s share of spare time going to people with less education.

In America, for example, men who did not finish high-school gained nearly eight hours a week of leisure time between 1985 and 2005. Men with a college degree, however, saw their leisure time drop by six hours during the same period, which means they have even less leisure than they did in 1965, say Mark Aguiar of Princeton University and Erik Hurst of the University of Chicago. The same goes for well-educated American women, who not only have less leisure time than they did in 1965, but also nearly 11 hours less leisure time per week than women who did not graduate from high school.

Americans are having a hard time finding opportunity for vacations these days. 33% of Americans are living with extreme stress daily. And nearly 50% of Americans say they regularly lie awake at night because of stress.

An analysis of holiday letters indicates that references to “crazy schedules” have dramatically increased since the 1960s. Moreover, celebrities on Twitter publicly complain about “having no life” or “being in desperate need for a vacation.”

Busyness and lack of leisure are also being more celebrated in the media. Advertising, often a barometer of social norms, used to feature wealthy people relaxing by the pool or on a yacht. Today, those ads are being replaced with ads featuring busy individuals who work long hours and have very limited leisure time. For example, recall Cadillac’s 2014 Super Bowl commercial featuring a busy and leisure-deprived businessman lampooning those who enjoy long vacations.

Dr. Susan Koven practices internal medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. In a 2013 Boston Globe column, she wrote: “In the past few years, I’ve observed an epidemic of sorts: patient after patient suffering from the same condition. The symptoms of this condition include fatigue, irritability, insomnia, anxiety, headaches, heartburn, bowel disturbances, back pain, and weight gain. There are no blood tests or X-rays diagnostic of this condition, and yet it’s easy to recognize. The condition is excessive busyness.”

Dr. Michael Marmot, a British epidemiologist, has studied stress and its effects, and found the root causes to be two types of busyness. Though he doesn’t give them official names, he describes the most damaging as busyness without control,which primarily affects the poor. Their economic reality simply does not allow for downtime. They have to work two to three jobs to keep the family afloat. When you add kids to the mix, it becomes overwhelming, and the stress results in legitimate health problems. The other type is busyness with control, which primarily affects the middle and upper classes. Although their economic reality allows for downtime, they don’t take it, but rather fill their time with an increasing variety of activities and consumer products to take care of. This kind of busyness also results in stress and legitimate health problems.

Busyness as a Badge of Succcess and “Humblebrag”

Brigid Schulte, in her 2014 book, Overwhelmed, writes incisively about this trend, “So much do we value busyness, researchers have found a human ‘aversion’ to idleness and need for ‘justifiable busyness.’” Researchers can track the rise of busyness in holiday cards dating back to the 1960s. In holiday cards, Americans used to share news about our lives (the joys and sorrows of the year), but now we’re more likely than ever to mention how busy we are as well.

How busy are you these days? The answer to that question says a lot about your social status, according to new research from McDonough School of Business Assistant Professor of Marketing Neeru Paharia.

“Long hours of work and lack of leisure time have now become a powerful status symbol,” wrote Paharia and her co-authors in their report, “Conspicuous Consumption of Time: When Busyness and Lack of Leisure Time Become a Status Symbol,” published in theJournal of Consumer Research.The busier people say they are or appear to be — whether or not they really are — the more important others perceive them to be, according to the study. In American culture particularly, complaining about being busy, or humblebragging, has become an increasingly widespread phenomenon, Paharia and her colleagues found.

Not only do we confer a higher status on busy people, but we also see them as in demand, competent, and ambitious, their research shows. Over time, the U.S. system has allowed for “the commoditization of labor,” in which people — not just goods and services — are susceptible to the law of supply and demand. Think of a real estate agent with whom you have trouble getting an appointment. You start to see that person as more valuable. “Somebody who’s busy is seen as being a scarce resource,” Paharia said. “You’re in demand, and therefore you become scarce.”

Part of the research also examined busyness-signaling products by comparing people who shop at Whole Foods with those who use Peapod, a grocery delivery service. Peapod users were seen as busier and having as much status as Whole Food shoppers, even though the brand Peapod is thought of as significantly less expensive than Whole Foods. Participants assumed Peapod shoppers were busier at work and had less time to shop. “Rather than flattering consumers’ purchase ability and financial wealth, brands can flatter consumers’ busyness and lack of valuable time to waste,” the researchers found.

“If you live in America in the 21stcentury you’ve probably had to listen to a lot of people tell you how busy they are. It’s become the default response when you ask anyone how they’re doing,” contends Tin Kreider, in his article, “The Busy Trap,” in the New York Times. He says often this is said as a boast, “disguised as a complaint,” but often these same people complain about being dead tired and exhausted.

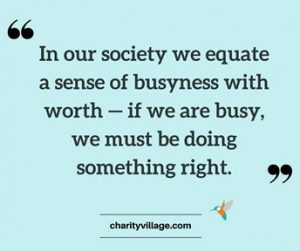

We live in a culture that celebrates being crazy busy: “Western society puts a high value on being busy,” wrote Dr. Christiane Northup, a women’s health expert and New York Times best-selling author. “We are conditioned to believe that being busy equates to being good, worthy, and successful.”

In his article for Harvard Business Review, renowned business leader Greg McKeown calls it “The More Bubble,” and argues society has granted us permission to be proud of being busy.

“This bubble is being enabled by an unholy alliance between three powerful trends: smart phones, social media, and extreme consumerism,” he explained. “The result is not just information overload, but opinion overload. We are more aware than at any time in history of what everyone else is doing and, therefore, what we ‘should’ be doing.”

“In the process, we have been sold a bill of goods: that success means being supermen and superwomen who can get it all done. Of course, we back-door-brag about being busy: it’s code for being successful and important,” he went on to suggest.

Where does the “supermen and superwomen” imperative come from? In the business world, it often comes from the cultural expectations of high achievement. As McKeown explains, it also comes from the impression we get that everyone is doing tons of cool stuff all the time. It’s an interesting take: Is our “addiction” to chaos and busyness driven more by habit and boredom — even shame?

Whatever it is, the busy humblebrag is just a coping mechanism. “Most of us aren’t genuinely proud of our chaotic lives … we just hide behind the reverence every time we fail to break the cycle,” McKeown says, “ And while being ambitious (to some degree) is obviously a great thing, it’s important that we don’t allow these cultural expectations to push us to the point of burnout.”

Even children today are overscheduled. Today’s adolescents and teens are overtaxed and overburdened and stressed to a degree that was once seen only in child psychiatric patients, according to an analysis of research spanning five decades by Jean Twenge, PhD, a psychology professor at San Diego State University. Statistics indicate 75% of parents are too busy to read to their children at night. There is a rising number of children being placed in day cares and after-school activities.

Alvin Rosenfeld, M.D., a child psychiatrist and author of The Over-Scheduled Child: Avoiding the Hyper-Parenting Trap, “Overscheduling our children is not only a widespread phenomenon, it’s how we parent today,” he says. “Parents feel remiss that they’re not being good parents if their kids aren’t in all kinds of activities. Children are under pressure to achieve, to be competitive. I know sixth-graders who are already working on their resume’s so they’ll have an edge when they apply for college.”

Kreider argues that overly busy people are busy because “of their own ambition or drive or anxiety, because they’re addicted to busyness and read what they might have to face in its absence…They feel anxious and guilty when they aren’t either working or doing something to promote their work.” He says that busyness serves as a kind of “existential reassurance, a hedge against emptiness.” For busy people’s lives cannot possibly be “silly or trivial or meaningless” if they are completely booked with activities, and “in demand every hour of the day.” Krieder contends that our culture has assumed a value position that idleness or doing nothing is a bad thing. But “idleness is not just a vacation, an indulgence or a vice,” he says, “it is as indispensable to the brain as vitamin D is to the body, and deprived of it we suffer a mental affliction as disfiguring as rickets.”

Busyness and Productivity

“Nowadays we’re expected to accomplish much more with our time,” says David Levy, Ph.D., professor at the School of Information at the University of Washington. In an attempt to get extra work done, we “multitask, always trying to do two or three things at the same time. So we may eat our fast-food lunch and conduct business calls while we’re driving or checking our email. Rarely do we focus our attention on just one task anymore.” A big negative to all this multitasking, he adds, is that it is far more intellectually draining than single tasking.

David Meyer from the University of Michigan published a study that showed that switching what you’re doing mid-task increases the time it takes you to finish both tasks by 25%. “Multitasking is going to slow you down, increasing the chances of mistakes,” Meyer said. “Disruptions and interruptions are a bad deal from the standpoint of our ability to process information.”

Microsoft decided to study this phenomenon in their workers and found that it took people an average of 15 minutes to return to their important projects (such as writing reports or computer code) every time they were interrupted by emails, phone calls or other messages. They didn’t spend the 15 minutes on the interrupting messages, either; the interruptions led them to stray to other activities, such as surfing the Web for pleasure.

When you try to do two things at once, your brain lacks the capacity to perform both tasks successfully. In a breakthrough study, René Marois and his colleagues at Vanderbuilt University used MRIs to successfully pinpoint a physical source for this bottleneck. “We are under the impression that we have this brain that can do more than it can,” Marois explained. We’re so enamored with multitasking that we think we’re getting more done, even though our brains aren’t physically capable of this. Regardless of what we might think, we are most productive when we manage our schedules enough to ensure that we can focus effectively on the task at hand. That implies doing less not doing more.

There are other factors at play as well. Mobile devices allow employees to be reached anywhere, anytime. “We can’t get away from work anymore,” says Gabe Ignatow, Ph.D., a sociologist at the University of North Texas who studies social change. “Even when we’re relaxing on the weekends, we’re often bombarded with emails, text messages and calls from the office.”

Other digital distractions—namely, social media—can make us feel even more inundated. “Many people feel like they have to keep up with the endless stream of Facebook, Twitter and other social media posts, so that consumes even more of our time,” Dr. Ignatow adds.

In terms of work, there’s the trend, particularly for managers and professionals, of staying late at the office and going in on weekends to get more done.

“Nowadays there’s this pressure that if we don’t work 50 to 60 hours a week, we’ll get laid off if our company is downsized,” observes Susan Mackey, Ph.D., a psychologist with the Family Institute at Northwestern University.

In households with children, both parents are often employed outside the home. According to the U.S. Bureau for Labor Statistics, more than 70 percent of mothers with kids under 18 are in the labor force, meaning they either have a job or are looking for one. By contrast, in 1960 only 20 percent of mothers worked outside the home.

With Mom employed, both parents have become busier. “Families are really overworked nowadays in the sense that they’ve turned the woman’s contribution from an at-home contribution to a money contribution, but the work at home still needs to be done,” states University of Chicago sociologist Linda Waite, Ph.D. Today’s mothers and fathers have to divvy up the work of stay-at-home mom between them and do that on top of their regular, paid jobs, she says.

When housework and child-care hours are added to time spent on jobs and commutes, Dr. Waite estimates many American fathers and mothers are each working 70-plus hours a week.

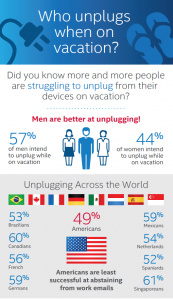

In essence, we have lost our belief in “dolce far niente,” how sweet to do nothing. Our inability to do this is exacerbated by our incapacity to unplug from the digital world. I argued in my article “Why it’s so hard to unplug from the digital world,” we may be actually addicted to the digital virtual world, which can physically disconnect us from others and our inner selves.

In my article in Psychology Today, “Workaholism and the myth of hard work,” I argued that a “contributing factor to the problem of workaholism is the prevailing belief in hard work as the route to success, particularly wealth. Notions of hard work are predominantly held by the middle class and poor people and originate from the industrial revolution and Protestant religious tenants, which viewed hard work both as a virtue and magic formula for success. Hard work has never been a belief embraced by the upper class and wealthy.”

We now equate busyness and overwork with productivity but the two are not the same. In the same way, we’ve equated “seat time,” that is time workers spend in their seats at their desks or in meetings, as equivalent to productive work. It may be the reverse.

In a New York Times article, “Let’s Be Less Productive,” author Tim Jackson defines productivity as “the amount of output delivered per hour of work in the economy.” Jackson’s perspective underscores that perception that productivity in all its forms is measured in economic terms and in terms of time. Jackson goes on to say, “time is money…We’ve become conditioned by the language of efficiency.”

Sara Robinson, writing an insightful article in Salon magazine, on the issue of overwork, “Bring Back the 40-hour Work Week,” says “150 years of research proves that long hours at work will kill profits, productivity and employees.” Yet, for most of the 20thcentury, the broad consensus among American business leaders was that working people more than 40 hours a week was “stupid, wasteful, dangerous and expensive—and the most telling sign of dangerously incompetent management,” Robinson argues.

Citing the work of Tom Walker of the Work Less Institute’s Prosperity Covenant, “That output does not rise or fall in direct proportion to the number of hours worked is a lesson that seemingly has to be learned by each generation.”

Robinson also cites the work of Evan Robinson, a software engineer who published a paper for the International Developers’ Association in 2005 that argued throughout the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s, and ‘60s research studies conducted by businesses, universities, industry associations and the military supported the shorter (maximum 40 hour) work week. The research indicated that productivity does not rise substantially in extended work days or weeks. Extensive data showed that longer hours of work actually resulted in reduced efficiency and catastrophic accidents, which brought with them substantial liabilities to employers. The research showed that extended hours resulted in reduced brain functioning and physical fatigue, which actually results in loss of productivity.

A Business Roundtable study found that after just eight 60-hour weeks the fall-off in productivity is so marked that the average team would have actually gotten just as much done and been better off if they’d just stuck to a 40-hour week all along. And at 70-or 80 –hour weeks, the fall-off happens even faster; at 80 hours, the break-even point is reached in just three weeks. Studies on this subject conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics , U.S. Department of Labor, Proctor and Gamble Company, , the National Electrical Contractors Association, and the Mechanical Contractors Association of American produced similar results. All of them showed that continuing scheduled overtime has a strong negative effect on productivity, which increases in magnitude proportionate to the amount and duration of overtime.

Critics of these studies cite the fact that they focus on physical jobs and don’t apply to the majority of employees who are “knowledge workers.” Robinson argues that research shows that actually knowledge workers actually have fewer good hours in a day than physical workers—about six. U.S. military research has shown that losing just one hour of sleep per night for a week will cause a level of cognitive degradation equivalent to a .10 blood alcohol level. And what’s worse, most of them “typically have no idea of just how impaired they are,” says Robinson. Robinson cites the follow-up investigations on the Exxon Valdez disaster and the Challenger explosion, where investigators determined that overworked, overtired decision-makers played a significant role in bring about those disasters.

So what has accounted for our sudden loss of memory of knowledge about working hours and productivity that pervaded most of the 20thcentury? Robinson points to two factors. The first of these is the development of technology as a cornerstone of our economy, and the culture at the center of that technology—Silicon Valley. The jobs there have attracted a unique breed of brilliant young men and women who fit a particular profile: “single-minded, socially awkward, emotionally detached and blessed (or cursed) with a singular, unique, laser-like focus on some particular area of obsessive interest. For these people, work wasn’t just work; it was their life’s passion and they devoted every waking hour to it, usually to the exclusion of non-work relationships, exercise, sleep, food and sometimes even personal care,” argues Robinson. Overwork and overtime didn’t even appear in their vocabulary.

The new technological corporate ethics and slogans reflected these young overworked employees. For example, Microsoft’s “churn’em and burn’em” which translated meant hiring young programmers fresh out of university and working them 70 hours a week or more till they dropped, and then firing them and replacing them with new ones. Fortunately, Microsoft has abandoned this practice.

The second and related development which strengthened the prevalence of overwork was management philosophy and leadership style. Taking management guru Tom Peters’ message of passion for work was translated into working more is the only answer to productivity. And so any aspiring manager or executive worth his salt, who worked 40 hours a week or less would not be considered promotable talent, or worse, laughed out of the office for appearing to be lazy.

The 2008 recession has entrenched the notion of overwork as a necessity now, as opposed to an optional strategy. The recession has resulted in massive layoffs across all industries, but the level of work expected of the employees who remain has not just remained the same, it has increased to compensate for lost employees. And even where businesses have shown some improvement now, managers are loath to rehire or hire new employees, because the norm of fewer employees with the impression of equal productivity is an argument against doing so. As Robinson argues, “for every four Americans working a 50-hour week, every week, there’s one American who should have a full-time job, but doesn’t. Our rampant unemployment problem would vanish overnight if we simply worked the way we’re supposed to by law.”

Busyness and Workaholism

A workaholic is a person who is addicted to work. The term generally implies that the person enjoys their work; it can also imply that they simply feel compelled to do it. There is no generally accepted medical definition of such a condition, although some forms of stress, impulse control disorder, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder can be work-related.

Workaholism is not the same as working hard. Although the term workaholic usually has a negative connotation, it is sometimes used by people wishing to express their devotion to one’s career in positive terms. The “work” in question is usually associated with a paying job, but it may also refer to independent pursuits such as sports, music and art.

A workaholic in the negative sense is popularly characterized by a neglect of family and other social relations. Similarly, people considered to be workaholics tend to lose track of time — voluntarily or involuntarily. For example, people might proclaim that they will spend a certain amount of time (e.g. 30 minutes) on their work, while those “30 minutes” ultimately become hours.

Experts say the incessant work-related activity masks anxiety, low self-esteem, and intimacy problems.And as with addictions to alcohol, drugs or gambling, workaholics’ denial and destructive behavior will persist despite feedback from loved ones or danger signs such as deteriorating relationships. Poor health is another warning sign. Because there’s less of a social stigma attached to workaholism than to other addictions, health symptoms can easily go undiagnosed or unrecognized, say researchers.

Clinical researcher Professor Bryan Robinson identifies two axes for workaholics: work initiation and work completion. He associates the behavior of procrastination with both “Savoring Workaholics” (those with low work initiation/low work completion) and “Attention-Deficit Workaholics” (those with high work initiation and low work completion), in contrast to “Bulimic” and “Relentless” workaholics — both of whom have high work completion.

Workaholism in Japan is considered a serious social problem leading to early death, often on the job, a phenomenon dubbed karōshi. Overwork was popularly blamed for the fatal stroke of Prime Minister of Japan Keizō Obuchi, in the year 2000.

In the U.S. and Canada, workaholism remains what it’s always been: the so-called “respectable addiction” that’s dangerous as any other. “Workaholism is an addiction, an obsessive-compulsive disorder, and it’s not the same as working hard.

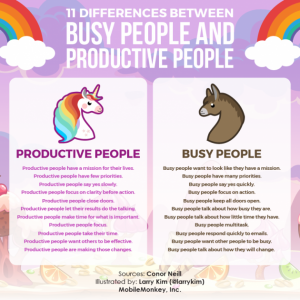

Workaholic’s obsession with work is all-occupying, which prevents workaholics from maintaining healthy relationships, outside interests, or even take measures to protect their health. Workaholics feel the urge of being busy all the time, to the point that they often perform tasks that aren’t required or necessary for project completion. As a result, they tend to be inefficient workers, since they focus on being busy, instead of focusing on being productive.

In addition, workaholics tend to be less effective than other workers because they have difficulty working as part of a team, trouble delegating or entrusting co-workers, or organizational problems due to taking on too much work at once. Furthermore, workaholics often suffer sleep deprivation which results in impaired brain and cognitive function.

As with other psychological addictions, workaholics often cannot see that they have a problem. Confronting the workaholic will generally be met with denial. Co-workers, family members and friends may need to engage in some type of an intervention to communicate the effects of the workaholic’s behavior on them. Indeed, mental treatment to cure a workaholic can successfully reduce the hours spent on the job, while increasing the person’s productivity.

Studies show that fully recovered former workaholics can accomplish in 50 hours what they previously couldn’t do in 80.

The Psychology of Busyness

If you’re reading this on your phone, rushing to work while hunting for your headphones, then you need to stop. At least, that’s what Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher who lived at the beginning of the 19th century, would advise. And indeed, as we race from the office to the gym to a dinner, proudly showing off our jam-packed schedules, it’s worth remembering Kierkegaard’s warnings about busyness long ago. He wrote: “Of all ridiculous things the most ridiculous seems to me, to be busy—to be a man who is brisk about his food and his work… What, I wonder, do these busy folks get done?”

Stephen Evans, a philosophy professor at Baylor University, explains that Kierkegaard saw busyness as a means of distracting oneself from truly important questions, such as who you are and what life is for. Busy people “fill up their time, always find things to do,” but they have no principle guiding their life. “Everything is important but nothing is important,” he adds.

Without answering crucial and terrifying questions about life, without deciding on a unified purpose, Kierkegaard believed that one could not develop a self. He called those with without one unified purpose “double minded,” and argued that this mindset causes busyness. And so busyness and lack of self are a bit of a chicken-and-egg situation. “If you don’t have a self, you don’t want to be aware of that,” Evans says. “You always have to stay busy.”

Kierkegaard’s concerns about busyness are also connected with his view of time, and the importance of living in the present. “The unhappy man is always absent from himself, never present to himself,” he wrote. In other words, obsessing over future goals, and keeping frenetically busy with an eye to some far-off date, is a way of distracting oneself from present reality.

By refusing to address the important questions in our lives, and instead living a “double minded” and busy life, we can be afraid to commit to a single person and cause, and so can lead to missing out on one’s calling or relationship. Comedian Aziz Ansari has made a similar point, suggesting that our incessant FOMO (fear of missing out) prevents us from focusing and fully committing to one person or one thing.

The problem, of course, is that we set expectations for a busy life as a culture, not as individuals. You can’t suddenly decide one morning to opt out of everything that’s demanded of you as a woman, man, parent or employee. Worse, the whole thing’s rigged: the expectations keep getting bigger. Get on top of your email, and you’ll find people send you more. Figure out how to spend sufficient time with your kids and at work, and you’ll suddenly feel some new social pressure – to spend more time exercising, cultivating a hobby or locating ethically sourced vegetables.

Most time management advice rests on the unspoken assumption that it’s possible to win the game: to find a slot for everything that matters. It’s just a matter either of shuffling the busy pieces, or shaving time off of the things that really sustain us in life—sleep, rest, solitude, eating leisurely. But if the game’s designed to be unwinnable, As Brigid Schulte suggests in her book Overwhelmed, you can permit yourself to stop trying. There’s only one viable time management approach left (and even that’s only really an option for the better-off). Step one: identify what seem to be, right now, the most meaningful ways to spend your life. Step two: schedule time for those things. There is no step three. Everything else just has to fit around them – or not. Approach life like this and a lot of unimportant things won’t get done, but, crucially, a lot of important things won’t get done either. Certain friendships will be neglected; certain amazing experiences won’t be had; you won’t eat or exercise as well as you theoretically could. In an era of extreme busyness, the only conceivable way to live a meaningful life is to not do thousands of meaningful things.

And “Learn to say no”: it’s such a cliché, and easy to assume it means only saying no to tedious, unfulfilling stuff. But “the biggest, trickiest lesson,” as the author Elizabeth Gilbert once put it, “is learning how to say no to things you do want to do” – stuff that matters – so that you can do a handful of things that really matter. Our only hope of beating overwhelm may be to limit, radically, what we’re willing to get whelmed by in the first place.

Being busy is not a virtue, and it’s not a badge of honor. We are human beings, not human doings.

Busyness and Our Concept of Time

Humans have always neededto tell time, but the clock, as we know it, wasn’t always the measure. For 10,000 years, humans lived in an agrarian culture and understood time through nature: the seasons, the rise and fall of the sun, and the sow-and-reap rhythm of crops. Eventually humans invented simple devices to mark the hours within a day—sundials, hourglasses, and water clocks, which used the regulated flow of water to measure time.

The first mechanical clock wasn’t introduced until the 13th century. With the Age of Enlightenment centuries later, a scientific desire for more precision led to clocks becoming a valuable tool for framing the world. In her book A Sideways Look at Time, Jay Griffiths explains that during the 17th and 18th centuries, time moved from a fluid measure to become more “absolute and deterministic.”

“The increasing precision of clockwork (coupled with the increasing number of clocks and watches) meant time was chiseled to fit snug to the clock,” Griffiths writes. “Time must be predictable, knowable, and visible.”

With the Industrial Revolution, minutes and seconds became a pervasive measurement of time for the common person. The rise of manufacturing regimented time with worker output. Productivity was king, and time translated to money. Today—as the Industrial Revolution cedes to the tech revolution—timekeeping is even more meticulous. We know the exact time in every corner of the world. We leap between time zones and are experiencing for the first time in human history a thing called jet lag, where technology and speed outpace the body’s biological capacity to keep up.

When time became money, our relationship to relaxation also changed. It used to be that the mark of accumulated wealth was leisure—restorative moments away from the toils of labor to enjoy other pursuits. Today, productivity is our top priority. Even the wealthiest among us toil away, packing schedules and squeezing every ounce of value from every second. Bill Gates gave up his golf game in “retirement” to do humanitarian work around the world because, as he told Fortune magazine in 2010, golf “takes up too much time to get any good at it.” (Golf courses around the world are developing nine-hole fast-track courses because people have become too busy to play 18 holes.) As we compete to be productive, busyness is as much a status symbol as anything else.

American employers, compared to those in other countries, offer workers the least amount of paid time off, according to statistics from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, with nearly one in four Americans receiving no paid time off. Even when a company does offer vacation time, Americans aren’t taking it. According to a study last year by Oxford Economics, the number of annual vacation days used by employees has steadily declined over the past 20 years, with Americans taking an average of just 16 days a year, less than half of what people take in many European countries.

“Imagine if a colleague at work asks how you’re doing, and you tell them that you’re great because you’ve cut back on your workload to take more time for yourself. They might think you didn’t care,” says Erik Helzer, a social psychologist and assistant professor at the Carey Business School. Helzer researches what makes people feel satisfied and fulfilled at work and in their lives. “There is a norm toward being busy—and that busyness confers your value,” he says. “Your potential worth is somehow wrapped up in the perceived lack of time you have.”

Here’s a surprising truth:Youare probably not as busy as you think you are. On average, Americans today have more free time than did previous generations. They are spending more time with their children than did parents of 40 years ago, despite a prevailing sense that they are not So why doesn’t it feel that way? The answer is in how we experience time in our minds.

“There is a distinction between objective time, which you can measure, and subjective time, which is experiential,” explains philosopher Nils F. Schott, at Johns Hopkins University. Schott, who specializes in the philosophy of time, explains that humans enjoy being busy when a task is fulfilling but can feel weighted when a task feels obligatory or when they feel pulled in two directions. There’s a difference between wantand should.

This pull can lead to what researchers call toxic time. We worry about what we should be doing for our kids while at work, or we worry about work while out on a date. We may want to exercise, or to stay late at work to complete a particularly fulfilling project, but we feel guilt over what else we should be doing. Time slips away in an unrelenting concern that we should be someplace else doing something more, or that we’re just not able to get to all of the things we hoped to. “We believe that we should be able to do and have everything,” Helzer says. “You’re going to be a great worker, a great partner, a great parent, a great child to your parents, and we’re forever trying to maximize our time.”

This is a big reason for our sense of overwhelm, according to Schulte. “We live under the crazy tyranny of our expectations—that we must be the ideal worker and put in endless hours at work and be the ideal parent and always be available to our children and always be busy and productive, yet doing enough cool stuff and working out and meditating so we’ll look good on our Facebook profile. These over-the-top expectations are actually driving what we think we can and should do in any given day,” she says. “If you are trying to cram a ton of stuff in your day, that creates an atmosphere where you’re breathless and stressed out and you feel powerless.”

Humans are also bad judges of how we actually spend our time. Helzer and colleague Shai Davidai, of Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, have been studying people’s perceptions of how they use their time. In one study, they asked participants on a Friday how they would spend their weekend. On Monday, they followed up to see how that time was actually spent. Participants who said they were going to do restorative activities—like reading a book or hiking in the woods—actually did things like plopping in front of the television. This leads to an interesting twist in our perception: We think we don’t have free time when we actually do. We’re simply frittering it away with mindless versions of passive leisure that don’t register as restorative. (According to the latest American Time Use Survey, the average adult spends nearly three hours a day watching TV.)

“People use rest in two different ways,” Helzer says. “One is in an intentional and rejuvenating way, such as sitting and reading, versus the mindless rest where we end up binge watching TV shows and you get up and say, ‘I can’t believe I just wasted three hours.’ What we found is that people believed they were going to have the more mindful kind of rest over the weekend, but when we interviewed them on Monday, they reported spending more time than they anticipated vegging out on the couch. So even though we have the time, we don’t tend to use it in a mindful way.”

In another study, Helzer and Davidai asked about personal development goals and found that people believed they would have more time in the future to pursue things that matter—like vacations, hobbies, or learning something new. Their research shows, however, that this magic time never materializes because humans continue to fill their days with other obligations once existing ones are complete. “The guiding force behind our findings is that if you wait for the opportune moment, it simply never comes,” Helzer says. “There’s no strong argument for delaying.

“If you look at the ingredients of a satisfying life, what our data show is that people are shortchanging themselves in the areas that may be most important,” Helzer adds. “The lesson is that you have to be intentional in carving out the time you want for the things that you want.”

Tim Kasser, a psychologist and professor at Knox College in Illinois, researches how Americans spend their time, and he’s been studying the inverse of our busyness epidemic: time affluence. In the 1990s, Kasser conducted research that found a correlation between financial pursuits and wellness. When people said that pursuing financial success was important to them, they also reported lower well-being.

Today, there have been many additional studies on this phenomenon, and the relationship between materialism and negative well-being is well-established, including studies that show the more people care about material things, the more they smoke and over consume alcohol.

“When we’re time affluent, it allows us to pursue values and activities like personal connections, and our relationship to our broader community. These values, in turn, do a good job of satisfying our psychological needs and promoting higher levels of well-being, ” he says, “In our rush to make more money and to have the American Dream as it’s been defined to us, we ended up crowding out our opportunity to have more time.” Kasser says “Any social system wants to maintain itself—whether it’s a religion or an economic system—and under corporate capitalism, we’re required to maintain certain beliefs. It’s important to work hard, to demonstrate success, to make money. Not only is there a lack of laws that support vacation and family leave, but there’s a continual message encouraging people to work hard and spend more. We internalize those messages, and busyness becomes a badge of honor.”

Kasser started considering the alternatives. “Time affluence means becoming affluent from a time perspective, rather than from a money perspective,” he says. “When we’re time affluent, it allows us to pursue values and activities like personal growth, personal connections, and our relationship to our broader community. These values, in turn, do a good job of satisfying our psychological needs and promoting higher levels of well-being.”

An Action Plan for Busyness

So the question is “what to do about busyness?” Here are some suggestions:

- Stop telling yourself (and others) how busy you are. In addition to coming across as humblebragging you’re telling yourself it’s a reality you can’t change which is not true.

- Cut your To Do list by 50%. And distinguish between what is “important” versus “urgent” which is usually someone else’s urgent.

- Develop a system or set of routines to deal with distractions.

- Stop multitasking. Productive people focus on one thing at a time.

- Learn how to say “no” frequently and affirmatively.

- Take regular frequent breaks during the day every day.

- Revisit your priorities and focus your efforts on them.

- Simplify your life including owning fewer possessions.

- Regularly seek out solitude (by yourself), preferably in nature.

- Focus on developing good habits, into which you place your goals.

- Seriously cut back on your commitment to activities, and don’t add new activities without dropping a current one

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.