Dwindling Support for Free Market Capitalism

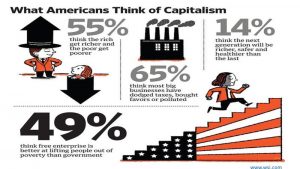

A study by Harvard University showing that 51% of Americans between the ages of 18 and 29 no longer support the system of capitalism, and asked whether the Democrats could embrace this fast-changing reality and stake out a clearer contrast to right-wing economics.It’s not only young voters who feel this way. A YouGov poll in 2015 found that 64% of Britons believe that capitalism is unfair, that it makes inequality worse. Even in the U.S., it’s as high as 55%. In Germany, a solid 77% are skeptical of capitalism. Meanwhile, a full three-quarters of people in major capitalist economies believe that big businesses are basically corrupt.

The capitalism imperative is to grow GDP, everywhere, year on year, at a compound rate, even though we know that GDP growth, on its own, does nothing to reduce poverty or to make people happier or healthier. Global GDP has grown 630% since 1980, and in that same time, by some measures, inequality, poverty, and hunger have all risen.

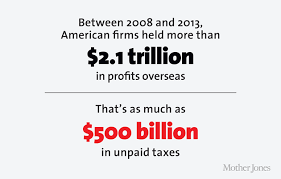

We also see this plan in the idea that corporations have a fiduciary duty to grow their stock value for the sake of shareholder returns, which prevents even well-meaning CEO’s from voluntarily doing anything good—like increasing wages or reducing pollution—that might compromise their bottom line.

For a startling example of this, consider the horrifying idea to breed brainless chickens and grow them in huge vertical farms, Matrix-style, attached to tubes and electrodes and stacked one on top of the other, all for the sake of extracting profit out of their bodies as efficiently as possible. Or take the Grenfell Tower disaster in London, where dozens of people were incinerated because the building company chose to use flammable panels in order to save a paltry £5,000 (around $6,500). Over and over again, profit trumps life.

It all proceeds from the same deep logic. It’s the same logic that sold lives for profit in the Atlantic slave trade, it’s the logic that gives us sweatshops and oil spills, and it’s the logic that is right now pushing us headlong toward ecological collapse and climate change. There are people in the U.S. fighting against the Keystone pipeline. There are people in Britain fighting against the privatization of the National Health Service. There are people in India fighting against corporate land grabs. There are people in Brazil fighting against the destruction of the Amazon rainforest. There are people in China fighting against poverty wages. These are all noble and important movements in their own right. But by focusing on all these symptoms we risk missing the underlying cause. And the cause is capitalism. It’s time to name the thing.

People want health care and education to be social goods, not market commodities, so we can choose to put public goods back in public hands. People want the fruits of production and the yields of our generous planet to benefit everyone, rather than being siphoned up by the super-rich, so we can change tax laws and introduce potentially transformative measures like a universal basic income. People want to live in balance with the environment on which we all depend for our survival; so we can adopt regenerative agricultural solutions and even choose, as Ecuador did in 2008, to recognize in law, at the level of the nation’s constitution, that nature has “the right to exist, persist, maintain, and regenerate its vital cycles.”

Measures like these could dethrone capitalism’s prime directive and replace it with a more balanced logic, that recognizes the many factors required for a healthy and thriving civilization. If done systematically enough, they could consign one-dimensional capitalism to the dustbin of history.

What is Capitalism?

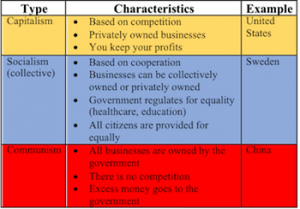

Capitalism can be defined as an “economic and political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state.”

Capitalism requires a free market economy to succeed. It distributes goods and services according to the laws of supply and demand. The law of demand says that when demand increases for a particular product, price rises. When competitors realize they can make a higher profit, they increase production. The greater supply reduces prices to a level where only the best competitors remain.Capitalism ignores external costs, such as pollution and climate change. This makes goods cheaper and more accessible in the short run. But over time, it depletes natural resources, lowers the quality of life in the affected areas, and increases costs for everyone.

Economists, political economists, sociologists and historians have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include laissez-faire or free market capitalism, welfare capitalism and state capitalism. Different forms of capitalism feature varying degrees of free markets, public ownership, obstacles to free competition and state-sanctioned social policies. The degree of competition in markets, the role of intervention and regulation, and the scope of state ownership vary across different models of capitalism.

The extent to which different markets are free as well as the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most existing capitalist economies are mixed economies, which combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases economic planning.Critics of capitalism associate the economic system with social inequality; unfair distribution of wealth and power; materialism; repression of workers and trade unionists; social alienation; economic inequality; unemployment; and economic instability.

Many socialists consider capitalism to be irrational in that production and the direction of the economy are unplanned, creating many inconsistencies and internal contradictions.Capitalism and individual property rights have been associated with the tragedy of the anticommons where owners are unable to agree. Marxian economist Richard D. Wolff postulates that capitalist economies prioritize profits and capital accumulation over the social needs of communities and capitalist enterprises rarely include the workers in the basic decisions of the enterprise.

Democratic socialists argue that the role of the state in a capitalist society is to defend the interests of the bourgeoisie.These states take actions to implement such things as unified national markets, national currencies and customs system. Capitalism and capitalist governments have also been criticized as oligarchic in nature due to the inevitable inequality characteristic of economic progress.

Capitalistic ownership means two things. First, the owners control the factors of production. Second, they derive their income from their ownership. That gives them the ability to operate their companies efficiently. It also provides them with the incentive to maximize profit. This incentive is why many capitalists say “Greed is good.”

The Advantages of Capitalism

Capitalism results in the best products for the best prices. That’s because consumers will pay more for what they want the most. Businesses provide what customers want at the highest prices they’ll pay. Prices are kept low by competition among businesses. They make their products as efficient as possible to maximize profit.

The Disadvantages

Capitalism doesn’t provide for those who lack competitive skills. This includes the elderly, children, the developmentally disabled, and caretakers. To keep society functioning, capitalism requires government policies that value the family unit.

Despite the idea of a “level playing field,” capitalism does not promote equality of opportunity. Those without the proper nutrition, support, and education may never make it to the playing field.

In corporations, the shareholders are the owners. Their level of control depends on how many shares they own. The shareholders elect a board of directors. They hire chief executives to manage the company.

The Problems With Capitalism Today

The global financial crisis, which began in 2008 and whose repercussions will continue to echo round the world for years to come, has triggered myriad criticisms of the modern capitalist system: it is too ‘speculative’; it rewards ‘rent-seekers’ over true ‘wealth creators’; and it has permitted the rampant growth of finance, allowing speculative exchanges of financial assets to be compensated more than investments that lead to new physical assets and job creation; and it rewards the rich while not passing economic gains onto the middle and poorer classes.

Debates about unsustainable growth have become louder, with concerns not only about the rate of growth but also its direction. Recipes for serious reforms of this ‘dysfunctional’ system include making the financial sector more focused on long-run investments; changing the governance structures of corporations so they are less focussed on their share prices and quarterly returns; taxing quick speculative trades more heavily; legally and curbing the excesses of executive pay.

Meanwhile, as Harvard Business Review points out, contemporary society is characterized by a sense of alienation among workers distanced from the output of their labor, and the fetishization of commodities—both predicted by Karl Marx. Inequality experts Jason Hickel and Martin Kirk launched a conversation on this site when they posed the theory that capitalism is at the core of the many crises gripping our world today.

In 2011, the same year that Occupy Wall Street injected dissatisfaction with the financial system into the American mainstream, Richard Wolff founded Democracy at Work, a nonprofit that advocates for worker cooperatives–a business structure in which the employees own the company, and share decision-making power over salaries, schedules, and where profits are directed. “If I had to pinpoint right now where the transition away from capitalism is happening in the United States, it’s in worker co-ops,” Wolff says.

These developments are all happening outside of the political system; in the White House and in Congress, the presence of big capitalist businesses continues as strong as ever. But the fact that local governments like New York City and Austin have launched incubator programs for worker-owned cooperatives indicates that they’re not incompatible with the current political system.

“Without us noticing, we are entering the post-capitalist era,” writes Paul Mason in the Guardian in an article entitled “The End of Capitalism Has Begun.” “At the heart of further change to come,” he continues, “is information technology, new ways of working and the sharing economy. The old ways will take a long while to disappear, but it’s time to be utopian.”

J. D. Moyer, says The aspects of capitalism that are not long for this world include:

- Ayn Rand/Gordon Gecko-style individualism, “greed is good,” disdain for cooperative efforts and collectivist values.

- Crass materialism and consumerism as acceptable social norms.

- Acceptance of worker exploitation, dehumanizing working conditions, extreme poverty, homelessness, poor nutrition, limited access to healthcare, and substandard education as “necessary costs” in a “free” market economy.

- The “predator/sociopathic” corporate charter model, under which corporations are legally obligated to prioritize profit-making over the environment, public health, worker health and safety, research and innovation, public and community wealth, and everything else.

In short, we’re moving towards humane markets (providing for each other) and away from human markets (exploiting each other).

Why is predatory, consumeristic capitalism on its way out? A number of factors are simultaneously converging:

- Human population growth is tapering off. Many people alive today will be alive to witness the most significant moment in our collective history — the human population peak. Capitalism is based on perpetual growth, which is not compatible with permanent population decline. Some of the challenges related to population decline will include abandoned cities, rewilding, and permanent economic shrinkage.

- We are running into severe environmental limitations. We have triggered the Anthropocene, a geological age characterized by mass extinctions, radical changes in local climates, overall global warming, acidification of oceans from excess CO2 absorption (which will result in almost no fish or coral reefs, but lots of jellyfish and algae), rising sea levels (and massive floods), endless droughts (resulting in the current Dustbowlification of the central US), deforestation, chemical pollution, gargantuan gyres of plastic detritus, and overall ecological shittiness. These problems are a direct result of a devouring capitalist system that sidelines such considerations as “externalities.”

- We are in the midst of a radical reorganization of production methods. More and more things are essentially free to produce and distribute, and can be shared/co-created via networks and decentralized production centers (home workshops, personal computers, 3D printers). Open-source production methods, freeware, and peer-to-peer distribution methods directly threaten top-down, strictly controlled capitalistic profit-generation models. Open-source is upending capitalism.

- Attitudes toward capitalism are changing. The United States, the world’s glowing beacon of capitalistic success, is no longer so shiny. Vast regions of our country display decrepit infrastructure. Cities are going bankrupt. Unemployment is high and underemployment is rampant. Millions go without access to professional healthcare. Its educational system produces only middling results. Wealth inequality is extremely high, and the tax-dodging, politically manipulating plutocrats are fighting tooth and nail to maintain their ill-gotten gains and privileges. Meanwhile, nations that lean more towards social democracy sport better infrastructure, better educated kids, nicer looking cities, cleaner environments, and healthier, happier citizens.

The 10,000-year pyramid scheme that has been generating wealth at the expense of non-renewable planetary resources has reached its limit. We have exhausted, in order, mega-fauna, pristine virgin forests, fossil fuels, free food from the ocean, fresh water sources, and an atmosphere that regulates temperature, rainfall, and local weather patterns. We have even used up some elements (like helium, which permanently escapes into outer space), and destroyed entire landscapes to extract gold, silver, copper, and rare metals.

Former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis has claimed capitalism is coming to an end because it is making itself obsolete.

The former economics professor told an audience at University College London that the rise of giant technology corporations and artificial intelligence will cause the current economic system to undermine itself. “So now there is no doubt capital is being socially produced, and the returns are being privatized. This with artificial intelligence is going to be the end of capitalism.”

A fundamental belief in our free enterprise capitalistic society is that competition is good because it benefits the people, the consumers. Rarely do we question that belief or display a willingness to look at the dark side of competition. Recent research has done just that.

First, take a look at competition among educational institutions for the best students, which is becoming increasingly an issue. According to Carmen Nobel, writing in the Harvard Business Schools’ publication, Working Knowledge, a senior admissions officer at Claremont McKenna College resigned after admitting to inflating reported SAT scores of the incoming classes for six years to boost the school’s rankings in the U.S. News and World Report’s annual report of top colleges and universities in the United States. Nobel argues that the scandal, which is not the first of its kind, “questions the value of competitive rankings, and the value of competition in general.”

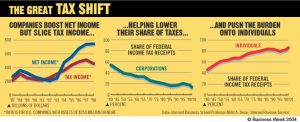

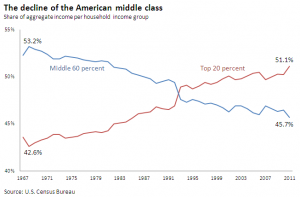

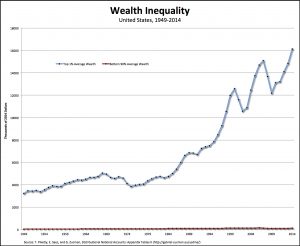

The rich are getting a lot richer, while most of us are losing ground. The issue of exorbitant financial compensation for the few is bringing into focus the problem of economic inequality in North America. Is our obsession with money at the core? It’s clear that economic inequality is increasing significantly in the U.S. Now the top 1% of Americans in terms of income receive the largest share of national income-the greatest since 1928. At the same time the share by the middle class is declining and the number of poor people is growing. Some hedge fund mangers made $4 billion annually, enough to pay the salaries of every public school teacher in New York City, according to Paul Buchheit of DePaul University. Today the average CEO’s pay is more than 250 times the average worker’s, whereas in 1965, it was only 25 times. According to the Wall Street Journal analysis of CEO compensation, the average CEO was paid $15 million in 2005 and the figure has increased dramatically. Goldman Sachs, one of the largest investment banks, just announced a new round of bumper bonus payments that will pay an average of $450,000 per person.

Tony Keller, writing in Report on Business, cites the work of University of Chicago economist Sherwin Rosen who investigated the issue of extreme compensation. Rosen examined the entertainment business, which often has the most dramatic examples of extreme compensation, publishing his work in a paper entitled, “The Economics of Superstars.” He identifies the superstars of compensation as hedge fund managers and recording stars such as Lady Gaga. James Simons of Renaissance Technologies, for example, has made more than $1 billion a year for at least the last 5 years. Keller poses this question, “Do hedge fund mangers deserve their paycheques? Do i-bankers? In a moral sense, surely not. They planted no crops, educated no children, built no homes, and saved no lives. Then again, neither did Lady Gaga. And the free market assigns compensation not on moral merit, but on supply and demand.”

Les Leopold, author of the book, The Looting of America, describes how Wall Street investment advisors convinced the Whitefish, Wisconsin school board and school boards from other districts to buy securities and CDOs that offered higher returns than treasury notes as a way of financing education in those districts. When the Wall Street collapse came, the school districts lost and owed huge amounts of money.

What is the impact of this inequality of compensation? What are public perceptions? Rik Kirkland, writing in Fortune magazine, described the issue of exorbitant CEO compensation. He cites a comment by Florida governor Jeb Bush, who said that out of control executive compensation isa “threat to capitalism.” According to a Watson Wyatt survey, 90% of institutional investors think top executives are dramatically overpaid. A Bloomberg national poll indicates that 70% of Americans say big bonuses should be banned for Wall Street firms that took taxpayer bailouts.

Benjamin Freedman, of Harvard University, and author of The Moral Consequences of EconomicGrowth, describes how throughout American history, most people didn’t object to rich people getting richer as long as the middle class also benefitted, and that is not longer happening. According toe a new study of CEOs by Jianyun Tang, Mary Crossan and W. Glenn Rowe, published in the Journal of Management Studies, dominant CEOs drive companies to extremes of performance and that boards of directors now rarely control those individuals.

Recent research seems to indicate that the rich are less adept at reading others’ emotions in comparison with uneducated and poor people, Michael Kraus, at the University of California, argues, who published his research in Psychological Science. He contends that wealthy people may be “less concerned and less perceptive of other people’s needs and wishes They show a deficit in empathetic accuracy.”

Linda McQuaig and Neil Brooks, authors of The Trouble with Billionaires, argue that increasing poverty due to economic inequality in the U.S. and Canada has detrimental effects on health and social conditions and undermines democracy. They cite the fact that while the U.S. has the most billionaires in the world, it ranks poorly in the Western world in terms of infant mortality, life expectancy, crime levels-particularly violent crime-and electoral participation.

In an article in the McKinsey Quarterly, authors Martin Dewhurst, Matthew Gutheridge and Elizabeth Mohr, cited numerous studies which concluded that for “people with satisfactory salaries, some non-financial motivators are more effective than extra cash in building long-term employee engagement,” and that “many financial rewards mainly generate short-term boosts of energy which can have damaging unintended consequences.” The authors concluded that many employers and chief executives hesitate to challenged the traditional managerial wisdom that money is what really counts. Despite our almost slavish devotion to the idea that increased wealth will increase our well-being, there is little evidence to support that belief.

Psychologists Ed Diener and Martin Seligman, in their article “Beyond Money: Toward An Economy of Well-Being,” published by the American Psychological Society, concluded “although economic output has risen steeply over the last decades, there has been no rise in life satisfaction during this period, and there has been a substantial increase in depression and distrust.” Diener and Seligman propose the creation of a national well-being index that includes such things as positive and negative emotions, engagement, purpose and meaning, optimism and trust, and a broad construct of life satisfaction as an equally important source for governments and leaders to develop economic and social policies. This contrasts significantly with the current popular measurement of financial wealth. Diener and Seligman point out that the life satisfaction levels for the Forbes magazine richest.

America’s prevailing paradigm about its economy and business has been that money is a system of power and the more our lives depend on money, the greater our subservience to those who control the creation and allocation of money, argues, David Korten, author of the best seller When Corporations Rule the World. Korten raises legitimate questions such as “why do we assume that maximizing financial return maximizes the creation of real value?” and “what about the many fortunes built through financial speculation, fraud, government subsidies, the sale of harmful products and the abuse of monopoly power?” Korten argues that there is a difference between real wealth which has intrinsic value (for example, land, food, knowledge, labor, water ) the value of which is beyond price compared to phantom financial wealth, which exists on paper, that has no intrinsic value. Increasingly people are becoming wealthy through phantom financial means. He concludes that Wall Street and its international extensions have “generated total phantom wealth claims far in excess of the value of the real world’s wealth, thus creating expectations of future security and comfort that can never be fulfilled.”

So what do we do about the problem? If the current trend continues, increasing numbers of the middle class will dip below the poverty line, and less than 2% of the population will control more than 90% ofthe wealth of our countries. The inherent danger to our economic and social fabric must be obvious. For decades, polymath futurist, Jacques Fresco has argued, as he did in an interview with Larry King, that money is the supreme corrupting influence and that we need to design a society free of money. He advocates the idea of collaborative consumption and the collective pooling of resources. One application may be online swapping instead of online shopping, an idea that the Wall Street Journal even identified as a legitimate and response to the recession. Whether Fresco’s solution is viable, or any other bold solution, one thing is clear-the current path will bring a lot of pain to a lot of people.

Chris Meyer and Julia Kirby, writing in the Harvard Business Review Blog and authors of a forthcoming book, Standing On The Sun (, argue that “exclusive reliance on economic measurement has aligned Western Capitalism around managing the financial resources that don’t create value.”

In their book, The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger, Professors Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, present data taken from multiple credible sources that show the gap between the poor and rich the greatest in the U.S. among all developed nations; child well being is the worst in the U.S. among all developed nations; and levels of trust among people in the U.S. among the worst of all developed nations.

That perspective was echoed in a research report entitled, Competition and Illicit Quality, by Victor Bennett of the USC Marshall School of Business, Lamar Pierce of Washington University’s Olin Business School, Jason Snyder of the UCLA Anderson School and Michael W. Toffel of Harvard Business School. They contend many companies in highly competitive industries are likely to bend the rules and cheat to keep their customers.

“Competition is generally thought to be good for companies because it keeps prices low and quality high. But when meeting customer demand is bad for society at large, then competition has a flip side, “ says Bennett, who led the research. The research was based on a study of 11,000 New York vehicle emission test facilities. The researchers found that companies with a greater number of local competitors passed cars with considerably high emission rates, and lost customers when they failed to pass the tests. Bennett and his colleagues concluded “in contexts when pricing is restricted, firms use illicit quality as a business strategy.”

Ernst & Young’s 12th annual Global Fraud Survey (2012) of more than 1,700 senior executives in 43 countries, including chief financial officers and heads of legal and compliance audits, showed 15% were willing to make cash payments to win or retain business. The corruption perception index of Transparency International, a multinational organization dedicated to curbing corruption in business, ranked countries according to its level of corruption. The U.S ranked 24th, with New Zealand first and Canada 10th, in terms of the absence of corruption.

In the Harvard Business Review, Malcolm S. Salter argues that the short-term focus of businesses invites corruption. He cites examples such as Wall Street’s mortgage banking fiasco, defining it as “institutionally supported behaviour that while not necessarily unlawful, undermines a company’s legitimate processes and core values. In the private sector, institutional corruption typically entails gaming society’s laws and regulations, tolerating conflicts of interest, persistently violating accepted norms of fairness and pursuing various forms of cronyism.” Salter contends that the excessive focus of executives on short-term results discourages long-term investments and weakens the economy.

That view is reflected in a Harvard Business School Working Paper by Nelson P. Repenning and Rebecca M. Henderson, entitled, “Making the Numbers? ‘Short Termism’ & The Puzzle of Only Occasional Disaster.” They argue “a vigorous tradition in the accounting literature establishes that firms routinely sacrifice long-term investments to manage earnings and are rewarded for doing so.”

In research conducted by the U.S. Business Roundtable Institute for Corporate Ethics, chief executives were asked to identify the most pressing ethics issues facing the business community. “Effective company management in the context of today’s short-term investor expectations” was among the most cited concerns. The report identified an excessive focus on short-term results because of intense competition as a factor in some executives’ willingness to engage in unethical practices.

So it seems that competition is not always good for consumers and society as a whole, particularly if it is driven by questionable ethical and short-term practices.

Signs of How Capitalism Is Failing Us

Reason 1: Rising Income Inequality.

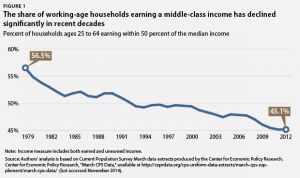

The Pew Foundation study, reported in the New York Times, concluded, “The chance that children of the poor or middle class will climb up the income ladder, has not changed significantly over the last three decades.” The Economist’ special report, Inequality in America, concluded, “The fruits of productivity gains have been skewed towards the highest earners and towards companies whose profits have reached record levels as a share of GDP.” I addressed the issue of income inequality in two previous articles in The Financial Post “How Income Inequality is Damaging Our Social Structure,” and “Will Income Inequality Cause Class Warfare?”

Kentaro Toyama, writing in The Atlantic, argues, is “inequality grows naturally from unfettered capitalism…If free market capitalism works so well for every income level, why have so many people seen income pass them by with capitalism working more efficiently than ever before?”

One possible reason is a moral foundation of capitalism—meritocracy. The term meritocracy is defined as a society that rewards those who show talent and competence as demonstrated by past actions or competitive performance. This concept is often interwoven with the widely accepted belief in the “self-made man” or “rags to riches” story. An OECD report concludes the only way to achieve fairness in a meritocracy is to provide more equal opportunities for everyone, not just the wealthy or privileged.

There is a clear connection between the alarming increase in income inequality and the prevailing paradigm of free market capitalism.

Nobel Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz’s book, The Price Of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future, provides an insightful analysis of the problem of income inequality. Stiglitz argues free market capitalism isn’t working the way it was supposed to, for it is neither efficient nor stable. He also says that political systems are unfair, which compounds the problem. Stiglitz contends “We are no longer country of opportunity and that even our long-vaunted rule of law and system of justice have been compromised.”

Stiglitz echoes Toyama’s perspective: “America has always thought of itself as a land of equal opportunity…[it is] now a myth reinforced by anecdotes and stories, but not supported by the data. The chances of an American citizen making his way from the bottom to the top are less than those of citizens in other industrialized countries.” Stiglitz says there is a corresponding myth—rags to riches in three generations—that once a person reaches the top they have to continue to work hard to stay there or their descendants will move down. The reality is that children of wealthy people usually remain at the top.

Who is to blame? Stiglitz casts a wide net but zeroes in on Wall Street. He says “Capitalism seems to have changed the people who were ensnared by it.” Much of what has happened can only be described by the words “moral deprivation.” What’s the solution? Stiglitiz, like many other expert observers, advocates policies that move toward a redistribution of wealth, not as an ideological solution, but as a practical one that will serve all in society and strengthen the economy.

The best selling book in the world currently is French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital In The 21st Century, which is a deep and thorough examination of economic inequality. Piketty outlines at great length the growth of capital (ie., wealth) and its concentration in the hands of the 1% and how increasingly wealth is inherited, not created or distributed anew. The big idea of Capital in the Twenty-First Century is that we haven’t just gone back to nineteenth-century levels of income inequality, we’re also on a path back to “patrimonial capitalism,” in which the commanding heights of the economy are controlled not by talented individuals but by family dynasties. His proposal to solve the income inequality issue is a progressive global wealth tax.

Robert Reich, an economist and former White House advisor, argues “if prosperity were more widely shared, we’d have faster growth. The rules are now designed to entrench and enhance the wealth of a few at the top and keep almost everyone else comparatively poor and economically insecure.” Reich argues that if we want to reduce the savage inequalities and insecurities that are now undermining our economy and democracy, we shouldn’t be deterred by the myth of the “free market.”

Reason 2: Obsolete Business Models.

Some people argue then, that today’s business organizations are oligarchies, created and strengthened by an unrestrained free market system. The Western world has adopted the concept and set of principles that govern them should be democratic which includes the consent of the governed. But since the rise of Western capitalism businesses operated on primarily a non-democratic basis. While businesses are owned by shareholders or owners, they are subject only to the laws of the jurisdiction in which they operate, but are not subject to the will of employees or their customers. In this way, it can be argued that most business organizations are like oligarchies.

Like our faith in a clearly broken system of free market capitalism, our theories and practices of management no longer work in today’s world. The problem is that, currently capital is downed in a speculative game. Most business organizations are geared toward wealth creation for financial markets not the improvement of life on this planet.

At the macro level, the “real economy” –that of the global exchange of products and services—has become poor man’s economy, representing less than 3% of the total amount of foreign exchange transactions

The endless emphasis on employee engagement is the narrow focus of efforts at organizational transformation. But for what purpose? What outcome? To be more productive? By producing more material things? At what social and environmental cost?

Roger Martin Dean of the Rotman School of Management argues in his book, Fixing The Game: “We must shift the focus of companies back to the customer away from shareholder value. The shift necessitates a fundamental change in our prevailing theory…that the singular goal of the corporation should be shareholder value maximization. Instead, companies should place the customers at the center of the firm.”

The corporate world needs to be redesigned to make it much more networked, interconnected, open, egalitarian, non-hierarchical, agile, transparent and empowering. Luis Suerez argues “The future of work is to freelance within organizations—choose your task, assemble to work, and then dissolve.” Many discussions about the future of work revolve around the need for more fluidity and freedom in the way work is done. But why do we continue to consider work as a separate entity from life? Isn’t each worker also a customer and a networked individual in a hyper-connected world.? And if we stop seeing work as separate from life, then we must see the notion of “worker” as also not being separate from management.

Business is now becoming a social enterprise. The Altimeter Group states, “Organizations moving into the “Business as Social” phase are driven by a vision that articulates how social media and digital overall improves customer and employee relationships and experiences.” Ann Marie McEwan, writing in her book, Smart Working-Crating the Next Wave, argues “Connected companies are not hierarchies, fractured into unthinking, functional parts, but holarchies : complex systems in which each part is also a fully-functional whole in its own right. A holarchy is a different kind of template than the modern, multidivisional organization.”

To understand customers fully, companies need to integrate them into their processes, make them integral part of the business ecosystem, and make them the part of the stakeholder system. Organizations in the new economy will not only have to be agile, tied to customers’ needs, but have to deal with dissolving boundaries, orchestrate resources they won’t own anymore through influence rather than control, according to Ranjay Gulati and David Kletter, authors of Shrinking Core: Expanding Periphery: The Relational Architecture of High Performing Organizations.

Michael Brenner, writing in Forbes, regarding the future of business identified 99 startling trends some of which are:

- More than 40% of the companies at the top of the Fortune 500 in the year 2000 were no longer there in 2010.

- There are now more mobile-connected devices on earth than there are people.

- 73% of people could not care if most name brands disappeared from their lives.

- More than 70% of the customers surveyed believe small businesses are more concerned about their needs than large companies.

- Only 7% of Gen Y employees work for a Fortune 500 company

- 90% of all internet traffic in 2017 will be video

- Hot new marketable skills for the future are jobs such as specialists in making transitions in life and work; experts in creating chaos in organizations for change; ethicists and philosophers to replace the HR function.

Nilofer Merchant, writing in the Harvard Business Review Blog, argues that the current and developing Social Era is the new context in which traditional strategy is dead. In the industrial era, organizations become more powerful by being bigger; in the Social Era, companies can also be powerful by working with others. Merchant says “While the industrial era was about making a lot of stuff and convincing enough buyers to consume it, the Social Era is about the power of communities, of collaboration and co-creation.

In the industrial era, power was from holding what we valued closed and separate; in the Social Era, there is another framework for how ee engage one another—an open one.” Companies cannot survive let alone prosper without recognizing that Social as a phenomenon can allow us to redefine our organizations to be inherently more fast, fluid and flexible by its very design, contends Merchant. Not by doing a little more, or sliming down a little, or by doing a few things a bit faster. Not by tweaking their way into the future.

Reason 3: Dysfunctional Management Practices.

While the old free market capitalism business model focused are shareholder value is becoming dysfunctional, so too are the management practices imbedded in this paradigm.

Gary Hamel, writing for the Harvard Business Review, calls for a new era of management thinking: “Equipping organizations to tackle the future would require a management revolution no less momentous than the one that spawned modern industry…executives and experts must admit that they’ve reached the Limits of Management 1.0—the industrial age paradigm built atop the principles of standardization, specialization, hierarchy, control and primacy of shareholder interests…they must cultivate, rather than repress, their dissatisfaction with the status quo…Why should so many people work in uninspiring companies? Why should the first impulse of mangers be to avoid the responsibilities of citizenship rather than to embrace them?”

Geoffrey James writing in the Business Insider, identified 7 terrible management fads that just won’t die, illustrative of the current broken model of business and management. These practices are:

- The idea of “best practices.” It’s a false assumption that what worked well for one company is transferrable to another. Also best practice awards are like the Academy Awards—recognition for past performance.

- Six Sigma. The practice of awarding people with different colored “belts” based on their expertise in Six Sigma methodology. The result is a hierarch of “belted” experts who go around advising people how to do their work, with little documented actual improvement in performance.

- Business Process Engineering. James says this is another euphemism for downsizing and layoffs.

- Matrix management. This means organizations group people with similar skills together for project assignments. The result is often endless turf wars and conflicts with multiple layers of management.

- Management by consensus. In theory this means important decisions are made with the agreement of everyone in the group. Since everyone has a say in the decisions, anyone can veto any decision. As a result, usually only innocuous decisions which support the status wquo are made. The difficult decisions are avoided.

- Core competence. In theory this means focusing on one thing the company does well. The reality is that most people in the organization are not self-aware enough to know what they are really good at. And the company rests on its laurels from the past, and stops innovating.

- Management by objectives. Simply described it means you define expectations or goals so management and employees agree and compare an employee’s performance with the goal/objective. However, in reality this turns into a paper work nightmare. The process of planning and evaluation takes more effort than the work itself. And the process doesn’t allow for sudden unexpected events or developments.

Steve Denning contends what we know about management is wrong. He says “We are in fact at the beginning of set of gigantic changes in society, in which everything we do is being re-invented-how we live, how we work, how we play, how we communicate, even how we think and how we feel. At the heart of these changes is of course the Internet and its related technologies.” Much of what we thought or knew about the economy doesn’t make sense anymore, despite the nightly news reviews fo the ups and downs of economic life, complete with statistics,, says Denning. There is no such thing as “the economy” anymore.

There are two economies going at “different speeds and on different trajectories. One economy is what Denning calls the Traditional Economy inherited from the 20th century—a world of factories, command-and-control, huge hierarchies churning out masses of products and services through a maze of delivery systems and huge capital investments in getting consumers to buy through sales campaigns and advertising. Although this economy is huge, it is declining, Denning contends. It doesn’t create new jobs, it is not agile and it is becoming increasingly inefficient and lacks innovation. And this economy is finding it increasingly more difficult to make profits. Denning concludes this economy has no future.

The other economy Denning descries is the Creative Economy—one of continuous innovation and transformation. This is an economy of entrepreneurs whose focus is delivery to customers things and services “better, faster, cheaper, smaller, more convenient and more personalized.” It is an economy focused on value and flexibility. It requires an empathetic connection to customers. In this economy the focus is shifted from the seller to the buyer. While this economy is smaller, says Denning; it is highly profitable and it is the economy of the future.

The kind of management required for the second economy is very different than the first economy. For one thing management cares about the environment and cares for people, Denning contends.

Management practices for the second economy will shift the goals of the organization, the structure of work, values and how people communicate. Denning summarizes these practices as:

- A shift from an inward-looking goal of making money and maximizing shareholder value to an outward-looking goal of profitably delighting customers.

- A shift from managers controlling individuals to a world where the manger’s role is enabling collaboration among self-organizing teams and networks.

- A shift from coordinating work by a bureaucracy to a world where work is coordinated with customers, networks and ecosystems.

- A shift from a single-minded preoccupation with efficiency and predictability to an embrace of values of transparency and sustainability.

- A shift from top-down directives to multi-directional connections.

Clearly the current free market business model is no longer serving society well, and income inequality will retard not advance economic prosperity. Tied to that reality is recognition that traditional management practices no longer work. The world has changed and the social nature of our world will require substantial changes to create a new economy.

From multiple perspectives, traditional business models and management practices are in deep trouble, and it has nothing to do with the recent economic downturn. There are three reasons why this is true.

Alternatives to Our Current Form of Capitalism

The alternatives to consumeristic predatory capitalism are not mysterious, nebulous, or theoretical. They are already operating and established in many ways, on both large and small scales. Some examples include:

- Dozens of countries (including most European countries, but also Canada and Japan) operate more or less as social democracies, and manage to provide healthcare, education, public safety, and other benefits to all of their citizens. Taxes are higher, but income and social inequality are lower. Social trust and happiness tend to be higher in functioning social democracies, which has a lot to do with more income equality.

- Large-scale cooperatives such as the Mondragon Corporation provides models for how to simultaneously achieve business excellence and social responsibility.

- Open-Source Ecology and their audacious Global Village Construction Set project provide a window into the future of open-source production and distribution methods (beyond information products and into the realm of functioning machines).

A new model of business, and indeed free market capitalism, is necessary because the old one is broken and out of date.In a white paper, “The Game Has Changed: A New Paradigm for Stakeholder Engagement,” produced for the Cornell University Center for Hospitality Research, author Mary Beth McEuen, Vice President of The Maritz Institute, says “In the ‘new normal’ environment, businesses must do more than merely offer a good product or serve to create value…customers, sales partners, or employees, all are looking for relationships with organizations they can trust…organizations that care…organizations that align with their own values. Instead of viewing people as a means to profit contemporary businesses must see their customers and clients as stakeholders in creating shared value.”

McEuen argues that traditional business beliefs that brought success in the past will not bring success in the future. People are very skeptical about businesses and a new approach is needed.Despite the rapid significant changes that have occurred in the world of business, the management philosophy has been anchored in the classical economics view of the company merely as a economic entity that has a goal of appropriating the greatest possible value from all its constituencies. In this view, McEuen contends, management’s core challenge has been to tighten the company’s hold over its stakeholders, find ways to keep competitors at bay, protect the firm’s strategic advantage and allow it to benefit maximally particularly for shareholders. The problem with this philosophy is that it is based on industrial-era paradigms that simply will not work in the new business and social environments.

In my National Post article, I said that the business world is fundamentally a community of people working together to create value for everyone in society, and that the pursuit by leaders of corporate and individual self-interest is a paradigm that has outlived its usefulness. That means a triple bottom line of profitability; social responsibility (both internally and externally) and sustainabililty must drive the capitalist engine. In my Financial Post article, I described some of the commentary at the World Economic Forum, which focused on the need to restrict narrow self-interest at the cost of collective good, and greater social responsibility. At the crux of both the articles is the issue of a sustainable and equitable economy, and the fallacy that unrestrained economic growth, particularly growth that benefits the wealthiest individuals and corporations, can lead to improved human welfare–or basically, growth at all costs.

It is clear now that we have to not just recover from an economic recession, but also reorganize the economy based on the quality of life rather than the quantity of life. The old model of business was based on a world with a small population, and a market economy as measured by GDP. But the world has changed dramatically. We live in a world with a large population and extensive capital infrastructures. Material consumption and GDP are merely means to the end of improving our well being, not ends in themselves. Material consumption beyond mere need actually can reduce our well being.From a management perspective, predominant theories of human behavior contained in business strategy and management are still mired in century old theories of transactional exchange and simple Skinnerian behavioral theories, ignoring the considerable neuroscience and human behavior research in the last decade.

For example, many business leaders still believe that people make decisions on the basis of rationality and logic, when we know from brain science that emotions always play a pivotal role.A new model of economy based on the goal of sustainable human well being for all people, not just a few, is needed, measured by factors that show sustainability, social equality and economic efficiency.This presents a real challenge for the proponents of the current free market system, which would mean implementing economic policy on the basis of issues such as social fairness—something that is often attacked by business leaders and politicians being either socialistic or communistic. Yet, it is clear that the market economy has actually contributed to declining levels of social fairness in our society and increasing numbers of employees and customers are disengaging from businesses.

A new form of capitalism and business would move away from a zero-sum game to one where every stakeholder benefits without trade-offs and where there is a higher purpose that serves as a motivational beacon for the leaders and culture. The new business norm, MCEuen argues, calls for a new set of capabilities within organizations, including social networks as a means of getting work done, deeply engaging knowledge workers in meaningful work and relating to customers in ways that are more personal. McEuen describes the new business norm, which has, as it’s conceptual foundation, “shared value”—where the total pool of economic and social value is expanded. There are three core premises that underpin this new business norm:

- Deeper insights into human motivation and behavior;

- An understanding that meaning for people is very personal;

- A commitment to the concept that people are at the center of strategy

As part of the old business paradigm, we continue to perpetrate the myth, particularly in the U.S., of individualism. That every individual and company has to struggle to make it on its own. So we’re taught to embrace the notion of man being a Lone Ranger, coming together with others only to accomplish self-interest purpose. Yet, as we know from brain science, our brains have evolved over millions of years in a social context of interdependence. We are “wired” to be social and seek out and develop social connections. In fact, studies have shown that emotions, attitudes and moods can spread among people like a virus. Similarly we know motivation is not only an individualistic thing; we are greatly influenced by the motivations of others, and we are driven by multiple motivations, not just simple material rewards.

What’s the difference? Steven Pressman says one thing: government. All the handouts, tax benefits, subsidies and rebates that transfer money into middle-class pockets. Without government help, Canada’s and Europe’s middle class would be endangered. Pressman , in his book, The Decline of the Middle Class: An International Perspective says says that in a modern global economy, the middle class can only be self-sustaining with active government programs, because the free market produces great inequalities of income. He says that contrary to popular belief, the countries that are doing well are the ones that have robust tax-and-spend programs. And an interesting caveat to Pressman’s assertion is that the countries that are helping their middle class the most are not doing so at the expense of the wealthy but at the expense of the poor.

The survival of the middle class is reliant on a thriving and open market economy, but its size and sustainability are equally dependent on the tax-and-spend mechanisms of the modern welfare state–which it turns out, are even more important in globalized, high competition economies. One caveat to this research is the explosive growth of the middle class in the developing economies in countries such as China, India and Brazil.

What About Socialism as an Alternative?

Socialism is a range of economic and social systems characterized by social ownership and democratic control of the means of production as well as the political theories and movements associated with them. Social ownership may refer to forms of public, collective or cooperative ownership, or to citizen ownership of equity. There are many varieties of socialism and there is no single definition encapsulating all of them, though social ownership is the common element shared by its various forms.

Socialist economic systems can be divided into non-market and market forms. Non-market socialism involves the substitution of factor markets and money, with engineering and technical criteria, based on calculation performed in-kind, thereby producing an economic mechanism that functions according to different economic laws from those of capitalism. Non-market socialism aims to circumvent the inefficiencies and crises traditionally associated with capital accumulation and the profit system. By contrast, market socialism retains the use of monetary prices, factor markets and in some cases the profit motive, with respect to the operation of socially owned enterprises and the allocation of capital goods between them. Profits generated by these firms would be controlled directly by the workforce of each firm, or accrue to society at large in the form of a social dividend.

Criticisms of Socialism

Economic liberals and right libertarians view private ownership of the means of production and the market exchange as natural entities or moral rights which are central to their conceptions of freedom and liberty and view the economic dynamics of capitalism as immutable and absolute. They thus perceive public ownership of the means of production, cooperatives and economic planning as infringements upon liberty

China’s Form of Socialism

The current economic system in China is formally referred to as a socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics. It combines a large state sector that comprises the commanding heights of the economy, which are guaranteed their public ownership status by law, with a private sector mainly engaged in commodity production and light industry responsible from anywhere between 33% to over 70% of GDP generated in 2005.Although there has been a rapid expansion of private-sector activity since the 1980s, privatization of state assets was virtually halted and were partially reversed in 2005. The current Chinese economy consists of about 150 corporatized state-owned enterprises that report directly to China’s central government. By 2008, these state-owned corporations had become increasingly dynamic and generated large increases in revenue for the state, resulting in a state-sector led recovery during the 2009 financial crises while accounting for most of China’s economic growth. However, the Chinese economic model is widely cited as a contemporary form of state capitalism, the major difference between Western capitalism and the Chinese model being the degree of state-ownership of shares in publicly listed corporations.

Scandanavian or Nordic Socialism/Capitalism

The Nordic model (also called Nordic capitalism or Nordic social democracy) refers to the economic and social policies common to the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Iceland, the Faroe Islands and Sweden). This includes an underlying social foundation of a comprehensive welfare state and collective bargaining at the national level with a high percentage of workers belonging to labour unions combined with the tenets of free market capitalism; and state provision of free education and free healthcare as well as generous, guaranteed pension payments for retirees funded by taxation. The Nordic model began to earn attention after World War II.

Canada, New Zealand and the U.K. have some elements similar to Nordic capitalism.

Although there are significant differences among the Nordic countries, they all share some common traits. These include support for a “universalist” welfare state aimed specifically at enhancing individual autonomy and promoting social mobility; a corporatist system involving a tripartite arrangement where representatives of labor and employers negotiate wages and labor market policy mediated by the government; and a commitment to widespread private ownership, free markets and free trade.

Each of the Nordic countries has its own economic and social models, sometimes with large differences from its neighbours. According to sociologist Lane Kenworthy, in the context of the Nordic model “social democracy” refers to a set of policies for promoting economic security and opportunity within the framework of capitalism rather than a replacement for capitalism. In the case of Norway, being the state owner of key industrial sectors, it has been described as XXI century socialism.

Summary:

While it can be debated about the relative merits or faults of some form of socialism, such as seen in Scandinavian countries, which exhibit high standards of living combined with high levels of social well being and democracy, in contrast to China or Russia, a close examination of free market style of capitalism which exists in the United States clearly shows some serious economic and social problems. How capitalism evolves there or declines will have global implications.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.