By Ray Williams

December, 2021

Current times are tumultuous. Political strife and violence, environmental degradation, corporate corruption and economic and social insecurity mark the daily lives of many. The times call out desperately for compassionate leaders.

How Leadership in the Modern Capitalist Era Lacks Compassion

Hershey H. Friedman, writing in Psychosociological Issues in Human Resource Management argues that ““There is a leadership crisis in the world today that is affecting government, business, and education. Young people are especially troubled over the lack of values displayed by leaders. Corporate leaders seem to be only concerned about finding ways to inflate their own salaries than in ensuring fair wages for employees. Despite all the talk about corporate social responsibility and business ethics, corporate leaders appear to be only interested in maximizing their own salaries rather than in ensuring fair wages for employees. Top CEOs now make approximately 300 times more than the typical employee. It appears that CEOs are reaping the rewards when they have little to do with successful performance of their companies; luck or chance usually has a greater effect on firm performance than the CEO’s talents.” Friedman cites the following:

- One study examining compensation among the top 200 companies using return on capital as a measure of CEO performance found that 74 out of the 200 firms overpaid their CEOs.

- CEO pay is up 997% since 1978.

- The median real salary (adjusted for inflation) of American male workers is $726 less per year than in 1973.

- The employment-population ratio, which is probably a more important measure than the unemployment rate, was above 63% before the Great Recession of 2008 and is currently at 59%.

- Analysis of an assessment instrument that measures empathy and com- passion of college students shows that concern for the well-being of others has been tumbling since the early 1990s and is currently at the lowest point in the last 30 years.

Friedman argues there has never been a more important time for leaders to be selfless and show more compassionate for their employees and the less fortunate.

I have been coaching and training leaders for more than 30 years. During that time, the leaders who had the greatest support by employees and achieved consistent results were the ones who exhibited the traits of empathy and compassion. In contrast, the leaders who are narcissistic, dominating and lacked compassion and empathy were less successful and respected.

What is Compassion?

The Latin root for the word “compassion” is pati, which means “to suffer” and the prefix com- means “with.” Compassion, originating from compati, literally means “to suffer with.”

The definition of compassion, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, is the “sympathetic consciousness of others’ distress together with a desire to alleviate it.” And the New Oxford American Dictionary defines compassion as “a sympathetic pity and concern for the sufferings or misfortunes of others.”

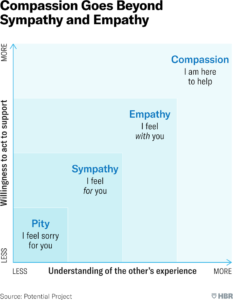

Empathy is an ability to relate to another person’s pain as if it’s your own. Empathy, like sympathy, is grounded in emotion and feeling, but empathy doesn’t have an active component to it that compassion does.

Research on Compassion

Compassion is not the same as empathy.

Neuroscientists Tania Singer and Olga Klimecki conducted studies comparing empathy and compassion. Two separate experiment groups were trained to practice either empathy or compassion. Their research revealed fascinating differences in the brain’s reaction to the two types of training. First, the empathy training activated motion in the insula (linked to emotion and self-awareness) and motion in the anterior cingulate cortex (linked to emotion and consciousness), as well as pain registering. The compassion group, however, stimulated activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex (connected to learning and reward in decision-making) as well as activity in the ventral striatum (also connected to the reward system).

Second, the two types of training led to very different emotions and attitudes toward action. The empathy-trained group actually found empathy uncomfortable and troublesome. The compassion group, on the other hand, created positivity in the minds of the group members. The compassion group ended up feeling kinder and more eager to help others than those in the empathy group.

Empathy is viscerally feeling what another feels. Thanks to what researchers have deemed “mirror neurons,” empathy may arise automatically when you witness someone in pain. For example, if you saw me slam a car door on my fingers, you may feel pain in your fingers as well. That feeling means your mirror neurons have kicked in.

Compassion takes empathy and sympathy a step further. When you are compassionate, you feel the pain of another (i.e., empathy) or you recognize that the person is in pain (i.e., sympathy), and then you do your best to alleviate the person’s suffering.

Compassion is a four-step process.

Thupten Jinpa, Ph.D., is the Dalai Lama’s principal English translator and author of the course Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT). Jinpa posits that compassion is a four-step process:

- Awareness of suffering.

- Sympathetic concern related to being emotionally moved by suffering.

- Wish to see the relief of that suffering.

- Responsiveness or readiness to help relieve that suffering.

Compassion hinges upon mindfulness.

The regular practice of mindfulness — moment to moment awareness of your body and mind — turns out to be a common theme across programs for training compassion, including those based at the University of Wisconsin, Emory University, CCARE, the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, Germany, a consortium of clinicians in the United Kingdom, and, of course, 2,000 years of Buddhist tradition.

We can learn how to be more compassionate

You weren’t born with a fixed amount of compassion. It turns out that compassion is a trainable skill, one that can be “exercised” like a muscle, says Dr. Richard J. Davidson of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Investigating Healthy Minds. Dr. Davidson conducted a study to determine if everyday people could learn to feel compassion for different categories of people, including “difficult” people in their lives.

Using an online meditation training program for 30 minutes each day, study participants gradually learned to focus on feeling compassion for others. After two weeks of practice, participants’ brain scans showed higher activity for altruistic behaviors. Moreover, study participants who received compassion training were more likely to act generously towards strangers.

A study by researchers at the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds at the Waisman Center of the University of Wisconsin-Madison shows that adults can be trained to be more compassionate. The report, published in Psychological Science, investigates whether training adults in compassion can result in greater altruistic behavior and related changes in neural systems underlying compassion.

“Our fundamental question was, ‘Can compassion be trained and learned in adults? Can we become more caring if we practice that mindset?’” says Helen Weng, lead author of the study and a graduate student in clinical psychology. “Our evidence points to yes.”

Compassionate people like helping the group more than self

Extending compassion toward others biases the brain to glean more positive information from the world, something called the “carryover effect.” Compassionate action — such as giving some of one’s own earnings to charity — also activates pleasure circuits, which some people call “the warm glow.” In the words of Dr. Jamil Zaki, a professor of psychology at Stanford, “humans are the champions of kindness.” But why? Zaki’s brain imaging data shows that being kind to others registers in the brain as more like eating chocolate than like fulfilling an obligation to do what’s right (e.g., eating brussel sprouts). Brains find it more valuable to do what’s in the interest of the group than to do what’s most profitable to the self.

Compassion is hard-wired into the human species

Compassion is reproductively advantageous, being part of the care-giving system that has evolved to nurture and protect the young according to researchers Paul Gilbert and J.L Goetz and colleagues. Compassion can be seen as having evolved from an adaptive focus on protecting oneself and one’s offspring to a broader focus on protecting others including and beyond one’s immediate kinship group according to Franz de Waal. Compassion may also have evolved in primates because it is a desirable criterion in mate selection and facilitates cooperative relationships with non-kin according to de Waal and Dacher Keltner.

Compassion also means not being overwhelmed by others’ suffering so that one becomes too self-focused.

The idea that compassion means approaching those who are suffering with non-judgement and tolerance — even if they are in some sense disagreeable to us — is central to some research and Buddhist beliefs Clara Strauss and colleagues, and the Dalai Lama conceptualize compassion for others not only as being aware of and moved by suffering and wanting to help, but also as including the ability to adopt a non-judgmental stance towards others and to tolerate one’s own distress when faced with other people’s suffering.

Compassion may have ensured our survival because of its tremendous benefits for both physical and mental health and overall well-being.

Research by Ed Diener, a leading researcher in positive psychology, and Martin Seligman, a pioneer of the psychology of happiness and human flourishing, suggests that showing compassion for others in a meaningful way helps us enjoy better mental and physical health and speeds up recovery from disease; furthermore, research by Stephanie Brown, at Stony Brook University, and Sara Konrath, at the University of Michigan, has shown that it may even lengthen our life spans. Another way in which a compassionate lifestyle may improve longevity is that it may serve as a buffer against stress. A new study conducted on a large population (more than 800 people) and spearheaded by the University at Buffalo’s Michael Poulin found that stress did not predict mortality in those who helped others, but that it did in those who did not.

Compassion has the capacity to change the world.

Research by Jonathan Haidt at the University of Virginia suggests that seeing someone helping another person creates a state of “elevation.” Have you ever been moved to tears by seeing someone’s loving and compassionate behavior? Haidt’s data suggest that elevation then inspires us to help others — and it may just be the force behind a chain reaction of giving. Haidt has shown that corporate leaders who engage in self-sacrificing behavior and elicit “elevation” in their employees, also yield greater influence among their employees — who become more committed and in turn may act with more compassion in the workplace. Indeed, compassion is contagious. Social scientists James Fowler of the University of California, San Diego, and Nicholas Christakis of Harvard demonstrated that helping is contagious: acts of generosity and kindness beget more generosity in a chain reaction of goodness. Our acts of compassion uplift others and make them happy. We may not know it, but by uplifting others we are also helping ourselves; research by Fowler and Christakis has shown that happiness spreads and that if the people around us are happy, we, in turn

become happier.

Mindfulness meditation enhances compassion

Although compassion appears to be a naturally evolved instinct, it sometimes helps to receive some training. A number of studies have now shown that a variety of compassion and “loving-kindness” meditation practices, mostly derived out of traditional Buddhist practices, may help cultivate compassion.

Self-compassion is as important as compassion for others.

Self-compassion, according to Kristen Neff, a self-compassion researcher, has three main elements:

- Self-kindness or having the ability to refrain from harsh criticism.

- The ability to recognize your own humanity or the fact that each of us is imperfect and each of us experiences pain.

- The ability to maintain a sense of mindfulness or non-biased awareness of experiences, even if they are painful.

Self-compassion is often intertwined with self-esteem, but they really are two distinct concepts. Self-compassion is more about self-acceptance and self-esteem focuses on favorable self-evaluation, especially for achievements, according to Neff. Self-compassion is not dependent on social comparisons or personal success. It’s more about recognizing and accepting your flaws, which is a process that often leads to growth and personal development.

Compassion in the Workplace

In an organizational context, good leaders must be able to exhibit and practice both empathy and compassion, although the impact of compassion is more important.

Historically, men have dominated the business landscape and still do today for the most part. Not surprisingly, male-oriented ideas and priorities — particularly dispassionate logical, rational problem solving perspectives — have dominated organizations. Conversely, love and compassion and are generally perceived to be female traits and perspectives, and, if seen in men, are viewed as a “weakness.”

There has been a revolution in organizational behavior literature in the past three decades focusing on the importance of emotions for employee attitudes, interpersonal relations and work performance. However, this research has neglected the basic emotions of compassionate love ( feelings of affection, compassion, empathy, caring and tenderness for others).

In order for the capacity of compassion to emerge at an organizational level, policies and initiatives need to be put in place to encourage compassionate responses to employees’ emotional needs. Despite challenges in finding convergence across complex behavioral models, there is a growing interest both conceptually and empirically in how compassion can provide an account of organizational behavior more accurate than conventional mechanistic models. Compassionate organizing happens when individuals in an organization react and respond to human suffering in a coordinated way.

Compassion is conceptualized as a form of emotional work and is developed through the theoretical model of noticing, feeling and responding according to Katherine Miller, writing in the Journal of Applied Communication Research Noticing involves recognizing the needs of others, the process of feeling involves connecting empathetically, and responding involves verbal strategies and environmental structuring to balance emotional and informational content.

P.J. Frost, in a piece on compassion for the Journal of Management Inquiry, argues “As organizational researchers, we tend to see organizations and their members with little other than a dispassionate eye and training that inclines us toward abstractions that no include consideration of the dignity and humanity of those in our lens. Our hearts, our compassion, are not engaged and we end up being outside of and missing the humanity, the ‘aliveness’ of organizational life.”

Jacoba M. Lilius and her colleagues contend in their chapter of The Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship, conclude that organizational models that assume human nature consists only of individual self-interests have been extremely limiting and new research points to the fundamental role of empathetic concern and compassion not only in social life but in the workplace.

A predominant dispassionate, logical approach that distances itself from compassionate love, develops reward systems and training and development methods and the cycle reinforces itself. You will rarely see management training programs or employee manuals that address principles of tolerance, selflessness, kindness and compassionate love. When unloving, dispassionate behavior is modeled by the leader, this sets the tone for the entire organization, and when replicated across many organizations, sets a norm for business. It’s not that dispassionate, coldly logical ways of running organizations have not met with success, because they and their leaders have. But what has been the cost in terms of relationships, employee morale and happiness?

In an article for the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley, Emma Sepalla, director of the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education at Stanford University, cites the growing incidence of workplace stress among employees. She argues that a new field of research suggests when organizations promote an “ethic of compassion rather than a culture of stress, they may not only see a happier workplace, but also an upward bottom line.”

Claudio Fernandez-Araoz, writing in the Harvard Business Review Blogs,argues that organizations must develop a “culture of compassionate coaching.” This means not merely focusing coaching employees on their weaknesses, “and that creating a ‘culture of unconditional love’ binds the team together.”

Tim Sanders, author of the book, Love Is A Killer App, argues “those of us who use love as a point of differentiation in business will separate ourselves from our competitors just as world-class distance runners separate themselves from the rest of the pack.”

Sigel G. Barsade at the Wharton School of Business and Olivia A. O’Neill at the University of Pennsylvania published an article in Administration Quarterly in which they describe their longitudinal study of the culture of compassionate love in organizations. They found compassionate love positively relates to employee satisfaction and teamwork and negatively relates to employee absenteeism and emotional exhaustion.

Barsade and O’Neill speculate that the reason for this is because in Western culture, the assumption is that love “stops at the office door, and that work relationships are not deep enough to be called love.” The authors contend most organizational culture literature has largely neglected emotions and there is no organizational theory that incorporates behavioral norms, values and deep underlying assumptions about the content of emotions themselves and their impact on employees. Instead, a focus on cognitive constructions of job satisfaction and employee engagement has been the focus.

Compassionate Leadership

Dirk van Dierendonck and Kathleen Patterson, writing in the Journal of Business Ethics, take a virtues perspective and show how servant leadership may encourage a more meaningful and optimal human functioning with a strong sense of community to current-day organizations. In essence, they propose that a leader’s propensity for compassionate love will encourage a virtuous attitude in terms of humility, gratitude, forgiveness and altruism. This virtuous attitude will give rise to servant leadership behavior in terms of empowerment, authenticity, stewardship and providing direction.

In the book Awakening Compassion at Work, authors Monica Worline and Jane Dutton describe two different ways that compassion manifests itself in leadership practices. They describe “leading for compassion” as actions that leaders take when they use their position or personal influence to direct organizational resources that alleviate suffering. For example, when leaders sanction paid time off for employees to help volunteer for disaster relief projects, they are leading for compassion. Leading with compassion is an interpersonal endeavor between a leader and an individual. One leads with compassion when he or she is fully present with an employee who’s recently suffered a loss. Although you may not always be able to influence organizational change due to your leadership role in the company, you always have a choice to exhibit compassion in a one-to-one setting.

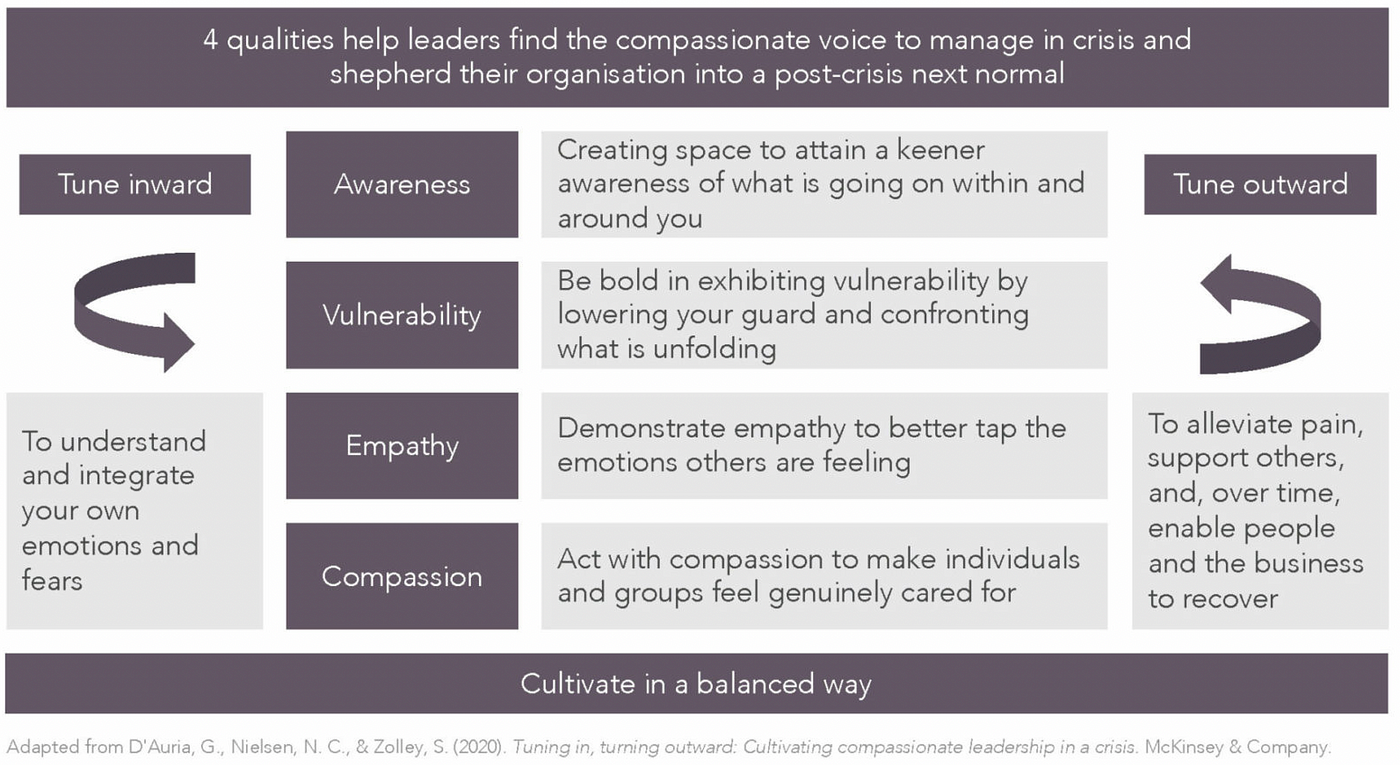

According to Rasmus Hougaard, Managing Director of Potential Project, leaders who dare to show compassion are rewarded with team members’ loyalty. He cites research by Professor Shimul Melvani, from the University of North Carolina’s Fliegler School of Business, who found that compassionate leaders have increased levels of engagement, and have more people willing to follow them.

“When we as leaders value the happiness of our people, they feel appreciated. They feel respected. And this makes them feel truly connected and engaged. It’s no accident that organizations with more compassionate leaders have stronger connections between people, better collaboration, more trust, stronger commitment to the organization, and lower turnover,” says Hougaard, whose consultancy provides leadership development training in the competencies of compassion, mindfulness and selflessness.

Of the over 1,000 leaders that Rasmus Hougaard, Jacqueline Carter and Louise Chester interviewed and reported on in the Harvard Business Review, 91% said compassion is very important for leadership, and 80% would like to enhance their compassion but do not know how. Compassion is clearly a hugely overlooked skill in leadership training.

Compassionate Leadership has emerged from the growing field of mindfulness, originally pioneered by Jon Kabat-Zinn as a means of reducing stress. The fact that compassion and leadership are rarely positively correlated is perhaps the very reason it’s resonating so widely. As global competition and heightened uncertainty has driven organizations to outsource, flatten and cut back (often quite mindlessly and heartlessly — the two tend to go hand in hand), people have become increasingly hungry for a deeper sense of meaning in their work and a closer connection between what they do and how it serves a greater good.

Compassion in the workplace could range from a dyadic act to a collective and organized act. Dyadic or individual compassion in the workplace is presented when an individual notices a colleague’s problem, feels empathy and takes action to help. This form of compassion depends on the compassionate person’s initiative to provide help and support and does not necessarily rely on any support from the organization.

Compassion at work may also take a collective form. In this form of compassion a group of colleagues gets involved in the compassionate act. Jason Kanov and his colleagues, writing in the American Behavioral Scientist identified this as “organizational compassion” which begins with an individual noticing a colleague’s problem, but becomes a social process with a group of colleagues acknowledging the presence of pain and feeling moved to take action in a collective way.

Roffey Park’s Compassion in the Workplace model identified the following elements of compassionate leadership in the workplace:

- Being alive to the suffering of others.Being sensitive to the well-being of others and noticing any change in their behavior is one of the important attributes of a compassionate person. It enables the compassionate person to notice when others need help. Noticing someone’s suffering could be difficult particularly in workplaces where people are busy with their work and preoccupied with their deadlines. Also depending on the work environment and the culture of the organization, people may tend to hide their pain from others.

- Being non-judgmental. A compassionate person does not judge the sufferer and accepts and validates the person’s experience. He or she recognizes that the experience of a single individual is part of the larger human experience and it is not a separate event only happening to this person. Judging people in difficulty — or worse condemning them — is one of the obstacles preventing us from understanding their situation and thereby being able to feel their pain.

- Tolerating personal distress.Distress tolerance is the ability to bear or to hold di cult emotions. Hearing about or becoming aware of someone’s difficulty may distress a compassionate person but does not overwhelm that person to the extent that it stops them from taking action. People who feel overwhelmed by another person’s distress may simply turn away and may not be able to help or take the right action.

- Being empathetic.Feeling the emotional pain of the person who is suffering is another attribute of a compassionate person. Empathy involves understanding the sufferer’s pain and feeling it as if it were one’s own.

- Taking appropriate action.Feeling empathic towards someone encourages the observer to take action and to do something to help the sufferer. Customizing actions depending on the sufferer’s personal circumstances is also important. Taking the right action depends on the extent to which we have made e orts to know the sufferer.

According to Fahri Karakas and Emine Sarigollo, “top leaders with higher ethical sensitivity evoke virtuous behavior in organizations. A compassionate leader initiates a cycle of positive change through 1) ethical decision-making 2) creating meaning and 3) inspiring hope and fostering courage for action that leaves a positive impact on the community. Genuine and intentional actions motivated by kindness result in shared benefits for the common good. Compassionate leaders nourish membership and use intentional attributes of love to enhance inclusion. They are moved by suffering and motivated by altruism to serve as a shining light to others. They give up their own goals in exchange for group decisions, do not need to know all the answers or be superior, and they listen instead of talk. Selfless leaders build relationships and respond to others to inspire higher levels of performance and purpose in their lives.

The road to becoming a compassionate leader requires self-reflection and personal transformation. Leaders who can evaluate their own strengths and weakness are better equipped to recognize and utilize the talents of others. They embrace employees as whole persons, discover human potential, create supportive teams, encourage positive engagement, and foster organizational growth and ethical membership in the community. There is a strong connection between compassionate leaders and ethical organizations: compassionate leaders act as catalysts.

Examples of Compassionate Leadership During the COVID Pandemic Crisis

Former President Donald Trump’s and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro’s polarizing, careless, and lying communication with the public stand in stark contrast to the approach taken by New Zealand’s Jacinda Ardern and Germany’s Angela Merkel.

Ardern, in her first address to the nation about her government’s pandemic response not only communicated in a clear and honest manner, but translated her empathic concern for her fellow citizens in a pleading message of compassion and unity: “Please be strong, be kind, and unite against Covid-19”. Ardern adopted a “go hard and go early” response to the pandemic, imposed a stringent nation-wide lockdown and deployed a rigorous national effort for testing, contact tracing, quarantine measures, and public education and engagement. The prime minister regularly acknowledged the hardships and extraordinary restrictions on personal freedoms these policies would bring to New Zealanders. Ardern’s compassionate leadership has resulted in high public confidence and adherence to a suite of relatively burdensome pandemic-control measures (Baker et a, effective reduction of the virus in New Zealand, and in overwhelming voter support and her subsequent victory in the national elections in October 2020.

Like Jacinda Ardern, chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany has empathized with the struggles of her German compatriots in her first address to the nation about the pandemic: “Our idea of normality, of public life, social togetherness — all of this is being put to the test as never before. […] We all miss social encounters that we otherwise take for granted. Of course, each of us has many questions and concerns in a situation like this, about the days ahead. But together we will weather the storm.” It is on the basis of these identified shared hardships that she has asked all citizens to support the governments Covid-19 policies.

In sharp contrast, Jair Bolsonario’s pronouncement when Brazil’s death toll was climbing rapidly was that Brazilians should resist the virus and that Brazil must stop being “a country of sissies” about the virus, because “all of us are going to die one day.” Similarly, Donald Trump, boasting about how he “beat” the virus, told people to “be strong” and fight back.

Pope Francis, who emphatically stated that “we must let ourselves be touched by others’ pain” to successfully chart our way out of the Covid-19 crisis, concedes that opening your mind and heart to the widespread conflict, suffering and need in the world around us can make us feel paralyzed and overwhelmed.

Leaders who are able to shoulder this emotional and intellectual toll, and who marshal the necessary strength for compassionate leadership can have a profound impact on the wellbeing of those around them. Studies show that compassionate behavior can have beneficial physical effects that can enable people to better cope with a demanding situation, develop resilience and bounce back.

As a consequence, compassionate leadership can help followers to develop resilience, bounce back and regain control over their lives — whether in the aftermath of a terrorist attack, or during a pandemic crisis. It is for all these reasons that leaders need to translate empathy into compassion. Not to show compassion in crisis means not to be effective as a leader.

Brad Shuck and colleagues published their research in Human Resource Development Quarterly in which they present research which shows “when leaders focused on compassionate behaviors during routine and focal events in the organization, six distinctive themes — integrity, empathy, accountability, authenticity, presence and dignity, emerged as individual-level building blocks of compassionate leadership behavior.”

Wendy E. Baraon, Arthur L. Costa and Robert J. Garmston wrote in their article “As Crisis Mount, Respond with Compassionate Leadership,” they argue “In compassionate cultures, members expose their confusion, doubts, worries, and failings as much as their convictions, successes, and joys. Leaders might be heard saying “I’m not sure what to do now” or “I don’t know how to …” and even “forgive me, I made a mistake,” confident that acceptance and nonjudgment are cultural norms. As leaders openly examine their own biases, feelings about others, predispositions, beliefs, mindsets, and past experiences, they open the door for other group members to examine their own biases and judgments. This openness and acceptance of one’s understory paves the way for more difficult conversations about such issues as equity, racism, environmental destruction, and social justice . . . . Most importantly, in compassionate cultures, leaders listen to understand, they suspend judgment, and respond with curiosity — inviting others to think, reflect, learn, research, create, innovate, share different points of view, and gain insights from one another.”

What Can Leaders Do To Be More Compassionate?

- Adjust your language: Using your words in a way that shows your understanding of how your people feel in certain challenging situations — empathizing with their situation, rather than merely sympathizing — can make an immense difference to how well you work as unit. Such phrases as “I can see how important this is to you”, “I know this can be frustrating”, “let’s see if we can solve this together” and “I’d like to help you if I can” strike at the heart of compassionate leadership as a form of “co-suffering”.

- Be authentic and don’t be afraid to share your shortcomings: Part of being a compassionate leader is about bringing your authentic self to the office every day. This will allow your people to feel comfortable in asking you for support, thus building a culture of trust and learning within your team

- Appreciate the views of others: Always attempt to envisage yourself in the shoes of your team members in every challenging scenario you face. Doing this will help you build a more inclusive team culture, one where everyone’s thoughts and ideas are heard, even if they don’t agree with yours.

- Create a psychologically safe team culture: Occasional errors and mistakes are to be expected. Compassionate will take steps to create a psychologically safe culture within their.

- Show gratitude. Demonstrate kindness by showing gratitude for everyone on your team, not just the top performers. Show them that you view them as more than employees and you see them as humans with individual needs.

- Show vulnerability. Research shows that leaders who are prepared to show their vulnerability more easily gain the trust of others, and are in fact, more effective leaders.

- Practice self-compassion. As research by Kristin Neff and Brene Brown has shown, people who engage in self-compassion are better at being compassionate toward others.

- Listen to others empathetically. Empathetic listening goes beyond the skill of active listening in that the leader is listening and noticing the emotional state of others while they are speaking.

- Show respect for others in word and action. This means not showing disrespect for others in what you say, how you say it, or not engaging in any behavior that is disrespectful.

- Demonstrate the Golden Rule. That means treating others as you want to be treated.

- Help others who are suffering. If one of your team members or employees is suffering through a painful situation, it’s important that you not only shown empathy for them, but that you offer to help them in some way.

- Take some time to self-reflect: Self-reflection is often the first step to becoming a more compassionate leader. Think about all the times when you may have tended to revert to less-than-desirable tactics when managing or leading your people. For example, perhaps a project deadline is fast-approaching — with a member of your team playing a crucial role — so, you ask them “…are you going to get it done on time?” Instead, in this situation, a more compassionate approach would be to ask them something like, “…the deadline is next week — do you have everything you need to get it done in time?”

Also read these other articles of mine:Does Wealth Make You Less Empathetic and Compassionate? And Why We Need More Empathy in the Workplace.

My Personal Blog: https://raywilliams.ca/category/blogs/articles/

Medium: https://raybwilliams.medium.com/

Financial Post: https://financialpost.com/author/raywilliamsnp

Sivana Spirit East: https://blog.sivanaspirit.com/author/raymondbwilliams/

Fulfillment Daily: http://www.fulfillmentdaily.com/author/raywilliams/

Read my latest books:

Toxic Bosses: Practical Wisdom for Developing Wise, Ethical and Moral Leaders available on Amazon in paperback, ebook and hardcover editions.

And,

I Know Myself and Neither Do You: Why Charisma, Confidence and Pedigree Won’t Take You Where You Want To Go, available on Amazon and Barnes and Noble in paperback and ebooks.