We’ve often heard the phrase, “I don’t like him but he gets results,” or reference is made comparing someone to a certain part of the anatomy while expressing some degree of admiration. In particular, our culture for some time has embraced the notion that the strongest, toughest and most aggressive leaders get the job done and are more desirable, than more “likeable,” or humble people who are viewed to be weak, ineffective or less successful.

So we have often also heard the expression that “nice guys” finish last, whether it’s in reference to the choice of a new CEO or a prospective date. But do nice guys really finish last? Or is that another myth we need to abandon?

New research by Jon Bohlmann and Rob Handfield of North Carolina State University, Tianjao Qiu of California State university, William Qualls and Deborah Rupp of the University Illinois published inThe Journal of Product Innovation Management, shows that project managers got much better performance from their team when they treated team members with honesty, kindness and respect. Bohlmann explains “if you think you re being treated well, you are going to work well with others on your team.”

Marshall Goldsmith, one of the world’s top executive coaches, writing in the magazine Fast Company, argues “all other things being equal, your people skills often make the difference in how high you go.” He says “it’s not enough to be smart—you have to be smart—and something else.”

David Rand, a post-doctoral fellow in Harvard’s Department of Psychology, is lead author of a new study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, which found that dynamic, complex social networks encourage their members to be friendlier and more cooperative, while selfish behavior can lead to an individual being shunned from the group.

Rand concludes people in social networks re-write their social networks in intriguing ways that helped both themselves and the group they were in. They were more willing to make new connections or maintain existing connections with those who acted generously and break connections with those who behaved selfishly. “Basically, what it boils down to is that you’d better be a nice guy, or else you’re going to get cut off,” he says.

These studies reflect a much bigger question of whether people essentially act out of self-interest, which would encourage the aggressive and egotistical to be more successful.

Dachel Keltner, a University of California psychologist and author of Born to be Good: The Science of a Meaningful Life, and a number of his fellow colleagues are building the case that humans are the successful dominant species because of our compassionate, kind, altruistic and nurturing traits. One of these studies has shown that many people are genetically predisposed to be empathetic.

“The new science of altruism and the physiological underpinnings of compassion is finally catching up with Darwin’s observations nearly 130 years ago that compassion is our strongest instinct,” argues Keltner.

University of California, Berkeley social psychologist Robb Willer, argues the more generous we are, the more respect and influence we wield. He contends “that anyone who acts only in his or her narrow self-interest will be shunned, disrespected, even hated, but those who behave generously with others are held in high esteem by their peers and thus rise in status.”

Martin Nowak and Roget Highfield, authors of SuperCooperators, contend “cooperation and competition are forever entwined in a tight embrace.” They argue in pursuing our self-interested goals we often have an incentive to repay kindness with kindness. We have an incentive to establish a reputation for niceness, so others will want to work with us.

Jonathan Haidt, author of Righteous Mind, reflects the view of Edward O. Wilson, David Sloan Wilson and others who argue that when groups of animals compete, it’s the cohesive, cooperative, internally altruistic groups that win and pass on their genes. Stephen Post, president of the Institute on Unlimited Love at Case Western Reserve University, and author of several studies published by such groups as the American Medical Association, and author of Why Good Things happened to Good People, has written about the link between good thoughts and good deeds.

Despite these recent findings, our movies, T.V., and news media continue to project the image of tough, no-nonsense leaders such as Donald Trump, who are not generally liked by other people, as examples of the kind of people we are drawn to, trust or wish to lead us, reinforcing the now clearly questionable notion of the survival of the fittest and strongest.

Modern evidence seems to suggest that nice guys do finish first, and we want them to.

The era of the command and control, charismatic leaders such as Jack Welch and Lee Iacocca, and projected in the extreme in movies by the character Gordon Gecko, may be over. In an era of increasing transparency and younger, more independent-minded, values driven workers, it no longer pays to be a jerk to employees, customers, vendors or competitors.

According to the book Return on Character,“character-driven” leaders who display four cardinal virtues — integrity, compassion, the ability to forgive and forget, and accountability — consistently deliver return on assets up to five times larger than the ROIs produced by their counterparts with a “self-focused” leadership style, who never or rarely exhibit those four traits. The book is based on a seven-year project by author Fred Kiel, founding partner of executive development firm KRW International. He and his research team studied 84 CEOs and more than 8,000 of their employees.

“A workforce that feels cared for is more productive than one that feels neglected, and that translates into bottom-line financial results,” Kiel notes. “So why do so many CEOs and their teams fail to create a work environment that promotes this kind of workforce engagement? Unfortunately, we … have seen that many senior leaders simply don’t know how to go about it and are afraid to try.”

Many of those fearful leaders belong to the type Kiel has dubbed “self-focused” — and the majority of them, over the seven years of the study, “failed to create significant value for their organizations, and two of them incurred major losses.”

In an article by Emma Sepalla in the Harvard Business Review entitled “The Hard Data on Nice Bosses,” she argues “Contrary to what many believe, Adam Grant’s data at Wharton School of Business shows that nice guys (and gals!) can actually finish first, as long as they use the right strategies that prevent others from taking advantage of them. In fact, other research has shown that acts of altruism actually increase someone’s status within a group.” Sepalla goes on to say:

- Harvard Business School’s Amy Cuddy and her research partners have also shown that leaders who project warmth – even before establishing their competence – are more effective than those who lead with their toughness and skill. Why? One reason is trust. Employees feel greater trust with someone who is kind.

- And an interesting study shows that when leaders are fair to the members of their team, the team members display more citizenship behavior and are more productive, both individually and as a team. Jonathan Haidt at New York University Stern School of Business shows in his research that when leaders are self-sacrificing, their employees experience being moved and inspired. As a consequence, the employees feel more loyal and committed and are more likely to go out of their way to be helpful and friendly to other employees. Research on “paying it forward” shows that when you work with people who help you, in turn you will be more likely to help others (and not necessarily just those who helped you).

- Such a culture can even help mitigate stress. While our brains are attuned to threats (whether the threat is a raging lion or a raging boss), our brain’s stress reactivity is significantly reduced when we observe kind behavior. As brain-imaging studies show, when our social relationships with others feel safe, our brain’s stress response is attenuated. There’s also a physical effect. Whereas a lack of bonding within the workplace has been shown to increase psychological distress, positive social interactions at work have been shown to boost employee health—for example, by lowering heart rate and blood pressure, and by strengthening the immune system. In fact, a study out of the Karolinska Institute conducted on over 3,000 employees found that a leader’s qualities were associated with incidence of heart disease in their employees. A good boss may literally be good for the heart.

Research by Jon Bohlmann and Rob Handfield of North Carolina State University, Tianjao Qiu of California State university, William Qualls and Deborah Rupp of the University Illinois, published in The Journal of Product Innovation Management shows that project managers got much better performance from their team members when they treated them with honesty, kindness and respect. Bohlmann explains “if you think you are being treated well, you are going to work well with others on your team.”

A study by Green Peak Partners, entitled “What Predicts Executive Success?” found the following:

- “Bully” traits that are often seen as part of a business-building culture were typically signs of incompetence and lack of strategic intellect.Such weaknesses as being “arrogant,” “too direct,” or “impatient and stubborn” correlated with low ratings for delivering financial results, business/technical acumen, strategic intellect, and, not surprisingly, managing talent, inspiring followership, and being a team player.

- Poor interpersonal skills lead to under-performance in most executive functions.Executives whose interpersonal skill scores were low also scored poorly on every single performance dimension.

- Leadership searches give short shrift to “self-awareness,” which should actually be a top criterion.Interestingly, a high self-awareness score was the strongest predictor of overall success. This is not altogether surprising as executives who are aware of their weaknesses are often better able to hire subordinates who perform well in categories in which the leader lacks acumen. These leaders are also more able to entertain the idea that someone on their team may have an idea that is even better than their own.

- Experience at many different companies is not a positive sign. The more organizations an executive worked with early in his or her career, the lower the people management rating. Executives who change jobs frequently are often trying to outrun a problem, and that problem often has to do with how they “fit” in the workplace. Job hoppers also lack perspective on the outcome of their leadership decisions, as they typically leave before the changes take effect.

In its 2014 leadership survey, the PR firm Ketchum wrote that there’s a “seismic move away from an outdated, ‘macho’ model of solitary leadership—a command-and-control approach centered on one-way rhetoric, obsessively controlled messaging and solitary decision-making—and towards a new, more ‘feminine’ archetype.” Though respondents to the survey still said they preferred male leaders by a slight margin (54 percent to 46 percent), they also said that women possessed more of the individual leadership characteristics they desired, like bringing out the best in others and being transparent. Women came out on top on 10 of the 14 leadership attributes the firm examined.

Studies that look at the effects of kindness and generosity over time suggest that the cynical phrase “nice guys finish last” is false outside of isolated events. While a pugnacious competitor may take advantage of a kind gesture, he or she sacrifices future cooperation in doing so.

The notion that nice guys finish last, i.e. that kindness and generosity put a person at a disadvantage, is allegedly supported by a thought experiment called the Prisoner’s Dilemma. In the experiment, two suspected criminals will turn each other in to receive shorter sentences.

But the problem lies in the experiment’s assumptions and limitations: that the prisoners share no innate concern for each other and the lack of context to their relationship. In the real world, relationships last longer than a single event, and purely self-interested behavior is a recipe for social isolation.

What About Nice Companies?

Peter Shankman, author of Nice Companies Finish Fist: Why Cutthroat Management Is Over And Collaboration Is In, outlines how employee dissatisfaction with their leaders is rampant and growing in organizations, largely because those leaders are “jerks” and abusive, and often, their companies reflect their leadership style.

Shankman profiles famously nice executives, entrepreneurs and companies that are setting the standard of success in our collaborative world, citing examples such as Jet Blue and Don Needleman, Zappos and Tony Hseigh, American Express and Ken Chenault and the whole team at Patagonia.

Shankman says companies should commit themselves to “enlightened self-interest,” which requires more than just the bottom line of financial results. Rather, they should have an equal focus on employee and customer welfare and doing something for the greater good.

Dave Kerpen and Theresa Braun and Valerie Pitchard, authors of Likeable Business: Why Today’s Consumers Demand More and How Leaders Can Deliver, argue “one thing is guaranteed in today’s hyper connected society: If your business isn’t likeable, it will fail.” They outline 11 strategies for organizations to become likeable and successful, including such things as transparency, authenticity and gratitude.

In their book, What’s Mine is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption, authors Rachel Botsman and Roo Rogers argue that a significant part of the growing collaborative economy is the concept of “reputation bank accounts,” that will measure and rank a company’s contributions to society. Firms which have high reputations will fare better than those with negative reviews and little in the bank.

The Parnassus Workplace Fund, started by Jerome Dodson in 2005, invests only in companies that have built solid reputations for treating employees with profound respect and supporting them through ongoing training and personal development and provides some meaningful form of profit sharing, health care and retirement benefits The Parnassus Workplace Fund has achieved annual returns just over 9.6%, and outperformed the S&P Index.

The reason smart business owners exude kindness is because they understand that kindness is more effective in business than being ruthless. Organizational psychology research has repeatedly shown that a negative, cutthroat environment leads employees to become disengaged. And a business with a disengaged workforce will experience, on average, 16% lower profitability and a 65% lower share price over time than a business with an engaged workforce, according to studies conducted by the Queens School of Business and the Gallup Organization.

Doug Sandler, author of Nice Guys Finish First argues the companies that win today understand the importance of having systems in place to provide exemplary service, making people a priority over products, putting the client experience at the top of the list and valuing relationships over technology. Successful businesses approach the future with an attitude of high touch over high tech.

Are success and niceness mutually exclusive? Not according to Linda Kaplan Thaler and Robin Koval, authors of The Power of Nice and the senior leaders of advertising agency the Kaplan Thaler Group argue “Ambition and nice are not mutually exclusive, and we have found that we get the best out of our team when we treat them well. We win business because we’re smart and creative and work hard for our clients and yes, we’re nice, too. But being nice doesn’t make us weak or vulnerable. We focus on doing the best possible work and coming up with big ideas for our clients.”

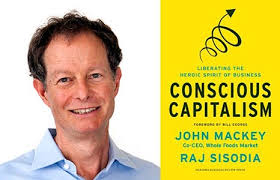

John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods, a much admired company, suggested that businesses look to transcendental Platonic ideals for inspiration: The Good (service to others—improving health, education, communication, and quality of life), The True (discovery and furthering human knowledge), The Beautiful (excellence and creation of beauty), and The Heroic (courage to do what is right and improve the world). A clearly defined higher purpose will serve as the foundation stone of the business and can inspire and galvanize all stakeholders.

For a conscious business, stakeholders go beyond that of only shareholders interested in short-term profits. Under a conscious business model, major stakeholders will include “customers, team members, suppliers, investors, the community, and the environment.” Each part is linked together and the success of one constituency is directly dependent upon the others. Conscious Capitalism, at its essence, “recognizes that business is the ultimate positive-sum game, in which it is possible to create a Win for all the stakeholders of the business.”

Raj Sisodia, Distinguished Chair of Business at Babson College, has marshaled an impressive array of evidence showing that conscious businesses are growing faster and are bringing in superior financial returns compared to their traditional competitors.

Fred Kiel, head of the executive development firm KRW international, recently studied 84 CEOs and more than 8,000 of their employees over the course of seven years. The results, written up in the Kiel’s recent book Return on Character, found that people worked harder and more happily when they felt valued and respected. So-called “character-driven” CEOs who possess four virtues—integrity, compassion, forgiveness, and accountability—lead companies whose returns on assets are five times larger than those of executives who are more self-centered, he found.

Competitive vs Cooperative

In their book SuperCooperators, by Martin Nowak with Roger Highfield, they use higher math to demonstrate that “cooperation and competition are forever entwined in a tight embrace.”

In pursuing our self-interested goals, we often have an incentive to repay kindness with kindness, so others will do us favors when we’re in need. We have an incentive to establish a reputation for niceness, so people will want to work with us. We have an incentive to work in teams, even against our short-term self-interest because cohesive groups thrive. Cooperation is as central to evolution as mutation and selection, Nowak argues.

But much of the new work moves beyond incentives. Michael Tomasello, the author of Why We Cooperate, found that at an astonishingly early age kids begin to help others, and to share information, in ways that adult chimps hardly ever do.

In his book, Born to Be Good, Dacher Keltner describes the work he and others are doing on the mechanisms of empathy and connection, involving things like smiles, blushes, laughter and touch. When friends laugh together, their laughs start out as separate vocalizations, but they merge and become intertwined sounds. It now seems as though laughter evolved millions of years ago, long before vowels and consonants, as a mechanism to build cooperation. It is one of the many tools in our inborn toolbox of collaboration.

In one essay, Keltner cites the work of the Emory University neuroscientists James Rilling and Gregory Berns. They found that the act of helping another person triggers activity in the caudate nucleus and anterior cingulate cortex regions of the brain, the parts involved in pleasure and reward. That is, serving others may produce the same sort of pleasure as gratifying a personal desire.

In his book, The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt joins Edward O. Wilson, David Sloan Wilson and others, who argue that natural selection takes place not only when individuals compete with other individuals, but also when groups compete with other groups. Both competitions are examples of the survival of the fittest, but when groups compete, it’s the cohesive, cooperative, internally altruistic groups that win and pass on their genes. The idea of “group selection” was heresy a few years ago, but there is momentum behind it now.

Human beings, Haidt argues, are “the giraffes of altruism.” Just as giraffes got long necks to help them survive, humans developed moral minds that help them and their groups succeed. Humans build moral communities out of shared norms, habits, emotions and gods, and then will fight and even sometimes die to defend their communities.

Different interpretations of evolution produce different ways of analyzing the world. The selfish-competitor model fostered the utility-maximizing model that is so prevalent in the social sciences, particularly economics. The new, more cooperative view will complicate all that.

Summary:

There is convincing research to show a connection among leadership behaviors marked by altruism, kindness, empathy and compassion—elements of being nice–generate greater employee engagement, productivity and wellness. There is convincing evidence that companies that demonstrate social responsibility and are nice to their employees and customers, thrive. It’s time to seriously question the outdated paradigm of a competitive, dog-eat-dog business world, driven by competitive, ruthless leaders.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.