“The reason they call it the American Dream is because you have to be asleep to believe it.”—George Carlin

The themes of self-reliance and personal responsibility as a means to amassing unlimited success has been an appealing story for more than a century. The self-made man myth, also described as “The American Dream” has been linked at various times to Benjamin Franklin, Ralph Waldo Emerson and the Horatio Alger stories. Not only is there little truth in the belief, but this oversimplified story has created an indelible view that there is neither responsibility nor the need to take care of one another, including those most vulnerable among us. It’s every person for himself or herself. And many self-help books and gurus have supplemented the fictional stories by emphasizing the values of independence and taking personal responsibility.

Movies, TV shows and popular media, and many politicians are reinforcing these myths by arguing and promoting the notion that anyone can be wealthy or make it to the top by virtue of their hard work and positive attitude and that’s how successful people did it in the past. We regularly read or hear about success stories like Bill Gates, Jeff Besos, Michael Dell, Richard Branson, Mark Cuban and a host of others.

And the self-made man myth is alive and well in Silicon Valley, built on the dream of the next killer app or technological device, where success stories of people like Steven Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg floods the mainstream media. It’s interesting to note that most “rags-to-riches” success stories are defined in terms of doing well in business and making lots of money. Yet rarely do we hear about the significant investments and contributions by some if not all of the following people: family, friends, associates, protagonists, antagonists, advisors, teachers, authors, mentors, coaches, and the list could go on.

The most recent recession in America and subsequent shifts in the global economy have disrupted many norms, including a realignment of assets and the demand and supply of talent. Along with these adjustments has been a renewed debate over issues such as the distribution of wealth, the disappearing middle class and the belief in meritocracy. Some recent experts have reaffirmed a perception that both the belief in the “self-made man” and the benefits of meritocracy are largely myths and prevent leaders from dealing with the serious problems of economic inequality, and social mobility.

Movies, TV shows and popular media, and many politicians are reinforcing these myths by arguing and promoting the notion—by idolizing wealthy people, such as Silicone Valley “Wunderkind,” famous celebrities, movie stars and professional athletes–that anyone can be wealthy or make it to the top by virtue of their hard work and positive attitude and that’s how successful people did it in the past. If this were true, we wouldn’t see a virtual explosion of people buying lottery tickets, and governments using lotteries as a significant source of revenue.

The “Self-Made” Man Myth and the American Dream

A “self-made man” (later expanded to include “self-made women”) is a classic phrase first coined on February 2, 1832 by United States senator Henry Clay who referred to the self-made man in the United States senate, to describe individuals in the manufacturing sector whose success lay within the individuals themselves, not with outside conditions.

Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, has been described as the greatest exemplar of the self-made man. Inspired by Franklin’s autobiography, Frederick Douglass developed the concept of the self-made man in a series of lectures that spanned decades starting in 1859. Originally, the term referred to an individual who arises from a poor or otherwise disadvantaged background to eminence in financial, political or other areas by nurturing qualities, such as perseverance, hard work, and ingenuity, as opposed to achieving these goals through inherited fortune, family connections, or other privileges. By the mid-1950s, success in the United States generally implied “business success”.

Horatio Alger’s words and quotes have often been used to reinforce the pioneering, go-it-alone, rugged heroism associated with early America. And by extension, his words have been co-opted to reinforce the idea that all Americans have a personal responsibility to themselves, for themselves. But the same sage who once said, “Make the most of yourself, for that is all there is of you,” also said, “Make yourself necessary to somebody.” Similarly in Ragged Dick, and many of the other stories penned by Horatio Alger, a young boy (Dick) was able to “pull himself up by his bootstraps” to achieve the American Dream despite a dire situation facing him. The “Horatio Alger Story” is one of the predominant and lasting American narratives.

The only problem is that many have reinterpreted this, and other stories like it, in such a way as to lose much of the original meaning. They are now used to suggest a literal “rags to riches” story where, through sheer hard work and determination, one can amass great wealth and success. What is lost is a concern for others that was always a central theme in his stories. The net definition of success wasn’t extreme wealth, but a middle-class place in society and a good reputation.

“A lot of Americans think the US has more social mobility than other western industrialized countries,” explains Michael Hout, a sociology professor at New York University and the study’s author. “This makes it abundantly clear that we have less.” Previous research used occupation metrics that relied on averages to gauge social status across generations. This dynamic, also called “intergenerational persistence,” is the degree to which one generation’s success depends on their parents’ resources. While these studies showed a strong association between parental occupation and intergenerational persistence, they understated the significance of parents’ jobs on the status of their children.

‘Middle points’ reveal more than averages

The findings, which appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveal a more powerful link as they rely on data that use medians, or middle points, as opposed to average socioeconomic status, in gauging occupations. Additionally, in almost all Horatio Alger stories, the protagonist is aided by a small coterie of friends and strangers who help make his success possible. The themes of self-reliance and personal responsibility as a means to amassing unlimited success is no doubt an appealing story. But it is a simplified narrative that has created an indelible impression among many Americans that there is neither responsibility nor the need to take care of one another, including those most vulnerable among us.

American Dream

The term American Dream was first used in James Truslow Adam’s 1931 best selling book, The Epic of America. Adams define the concept as “the dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with an opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement.”

In her book, , Facing up to the American Dream, Jennifer Hochschild identified four tenets of the American Dream:

- Everyone regardless of origin or status can attain the American Dream.

- The American Dream is a hopefulness for success.

- The American Dream is possible through actions that are under the individual’s direct control.

- Because of the associations of success and virtue, the American Dream comes true.

Meritocracy

The term meritocracy is defined as a society that rewards those who show talent and competence as demonstrated by past actions or competitive performance.The meritocratic ideals that were to inform French and American revolutionary periods had their origin in Confucian values that were instituted in Chinese civilizations such as the Han Dynasty. These social reforms were taken in order to displace a ruling class based upon family inheritance, with civil bureaucracy based upon merit, as demonstrated through educational attainment, competitive examinations and performance of one’s duties once appointed. Meritocratic ideals were eventually adopted by European Enlightenment thinkers (e.g., Voltaire) in efforts to reconstitute the social order beyond the confines of the ancient regime, and the more quotidian applications of meritocracy in Europe and the United States were used in the civil services as protective measures against corruption and political favoritism.

The U.S. is viewed by most of its citizens as a “land of opportunity.” According to this belief, anyone who comes to America have the opportunity to “pull themselves up by their bootstraps,” and succeed as long as they work hard and persevere. Those who are most worthy of America’s bounty are the meritorious. This social ideal promulgates the belief that, “those who are the most talented, the hardest working and the most virtuous get and should get the most rewards,” argue S. McNamee and R. Miller, in their book, The Meritocracy Myth.

The term “Meritocracy” was first used in Michael Young’s 1958 satirical book, Rise of Meritocracy, which describes a dystopian future in which one’s social place was determined by IQ and effort. Young described a society where those at the top of the system ruled autocratically with a sense of righteous entitlement while those at the bottom of the system were incapable of protecting themselves against the abused leveled by the merit elite above. The meritocracy was cruel and ruthlessness. Today, meritocracy is often used with a positive connotation to describe a social system that allows people to achieve success proportionate to their talents and abilities.

Nigel Nicholson, professor of organizational behavior at London Business School, argues in an article in The Harvard Business Review, that it is a damaging myth that meritocracy in organizations is based on the proposition that it equals quality and efficiency. Nicholson says “in the kind of meritocracy that companies try to implement, people progress linearly: The very best alpha sits on high, with a team of betas reporting to him (occasionally her), all the way down to the omegas working the machines and dealing with the customers.” He says that this approach does not work for 3 reasons: It allows for no scope for learning because people can’t change their grades; it ignores the fact that peoples’ value or talent depends on circumstances–everyone has unique capabilities that have to be constantly reassessed; and you can’t reduce a person’s value to a single letter or number on a scale of merit.

Nicholson argues that meritocracy has too many managers looking over their shoulders, striving to improve themselves instead of trying to bring out the best in others. He observes that a rigid hierarchical model has held sway in human society for more than 10,000 years. He says that our love affair with corporate hierarchy plays right into the hands of our ancestral primate instincts for contest, dominance and pecking orders–traditional obsessions and addictions of men in a patriarchal order.

What does Nicholson suggest as solutions? He says a true meritocracy would acknowledge all workers’ multiple talents. It would recognize that we live in a dynamic and uncertain world, and structures would be fluid and changing, citing Google, Opticon, Chapparal Steel and others who have experimented successfully with team based cultures, fuzzy hierarchies and spontaneous self-organizing projects.

Society is becoming more divided because wealthy and powerful figures are promoting the notion of a meritocracy while failing to address inequality, according to a new book by a sociologist at City, University of London.The book, Against Meritocracy: Culture, power and myths of mobility, traces the history of the idea of meritocracy and uses case studies from Dr Littler’s own research to show how popular culture and advertising are being used to support the notion.She says: “My research shows how the idea of meritocracy is today an inescapable part of our culture. It’s all around us, not just in the political world, but in media, education and in stories told about work. It contains a grain of truth and a whole heap of mystification.”

More recently, however, concerns about the actual effects of meritocracies are rising. In the case of gender, research across disciplines shows that believing an organization or its policies are merit-based makes it easier to overlook the subconscious operation of bias. People in such organizations assume that everything is already meritocratic, and so there is no need for self-reflection or scrutiny of organizational processes. In fact, psychologists have found that emphasizing the value of merit can actually lead to more bias in favor men.

Ironically, despite growing recognition of the pitfalls of meritocracy for women and minorities, the concept has been exported to developing countries through economic policies, multilateral development programs, and the globalization of media and curricula. In countries with deep social divisions like India, where the number of women in the workforce dropped 11.4 percent between 1993 and 2012, the mantra of meritocracy has taken hold as a potential means to overcome these divides and drive economic growth—especially in education.

The meritocracy myth is the product of two intertwined beliefs. The first, which is critical to the structure of the myth, is the belief that employment discrimination no longer exists for blacks and women. It is a conception of discrimination as traditional prejudice: overt, conscious, and negative bias.While acknowledging that historic discrimination once served to compromise the American belief in equal opportunity, such discrimination is now considered a relic of the past. Second, because race and sex discrimination no longer restrict employment opportunities for qualified blacks and women, current employment decisions are viewed as objective and fair. Unless affirmative action interferes with the decision making process, the belief is that merit alone ensures that the most qualified individual receives the job. According to the myth, differences in outcomes result not from unequal opportunity and discrimination, but from unequal talent and effort.

According to the meritocracy myth, then, differences in outcome result not from·discrimination but from merit. Those who succeed deserve to do so because they are more talented and they work harder than their colleagues. Support for this belief is found in a study by James Kluegel of white Americans’ beliefs about the reasons for the continuing gap in socioeconomic status between white and black Americans. Almost 31% of white Americans believe that the black-white socioeconomic gap is due solely to individual differences between the races: either differences in innate ability to learn or differences in motivation to succeed.Almost 65% of white Americans base the black-white socioeconomic gap, in part, on individual failings, like lack of motivation or ability.What is interesting is that even among those white Americans who, in part, attribute a structural reason, such as discrimination or educational opportunities, for the existence of the black-white socioeconomic gap, there is only weak support for programs to achieve racial equality.

Today, the beliefs in the American Dream and meritocracy have merged. According to the American Dream ideology, America is a land of limitless opportunity in which individuals can achieve as much as their own merit allows. Merit is generally defined as a combination of factors including innate abilities, working hard, having the right attitude and having high moral character and integrity, argue McNamee and Miller. If a person possesses these qualities and works hard they will be successful. Americans not only tend to think meritocracy is how the system should work, but most Americans also think that how the system does work.

Hard Work

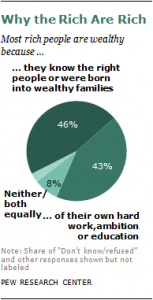

Hard work is seen as a powerful factor in meritocracy and a necessary element for acquiring the American Dream. National surveys have found that hard work consistently scores among the top three factors necessary for success, and ranks with education and knowing the right people as its closet competitors. According to one survey,about 77% Americans believe that hard work is often or very often the reason why people are rich in America. More than a third of all Americans — and more than half of all Republicans — believe that the rich are rich because they worked harder than everyone else. When pressed for proof, they usually point to surveys showing that the rich spend more hours working and fewer hours in “leisure activities” than everyone else. A 46% plurality believes that most rich people “are wealthy mainly because they know the right people or were born into wealthy families.” But nearly as many have a more favorable view of the rich: 43% say wealthy people became rich “mainly because of their own hard work, ambition or education,” largely unchanged from a Pew survey in 2008.

Researcher Barbara Ehrenreich found, when she spent a year doing menial jobs in a participant observation study, often the hardest working Americans are those who get paid the least.

America is an individualistic society, most people in it believe that success is directly correlated to hard work., Yet, as McNamee and Miller point out in their research, many people who work hard are not especially successful.

Value Conflicts

Most Americans are not aware of their own value conflicts when issues of merit are raised. A review of the theoretical literature shows that there are many direct conflicst when one thinks about meritocracy. Richard Longeria states several examples of these conflicts: “Working for what one has may conflict with rewarding intelligent people because natural intelligence is not earned. Giving everyone an equal opportunity may conflict with the notion that parents should favor their own children over the children of others. Favoring the intelligence and hardworking will create an unequal society, and if one supports genetic superiority arguments, lead to a caste system without social mobility. Allowing wealthy individuals the freedom to spoil their offspring conflicts with the ideal that every child should start life with the same chance to succeed. And support for democracy may mean that we should not elevate the smart and hardworking above the common person.”

A Critique of the Myths

Contrary to widespread societal belief, American society is not a meritocratic system, but continues to be presented and believed as one.

Education has been the American answer to all the issues in the country from waves of immigration to the abolishing of subordination based on race, class, gender, sexual orientation and other marginalized groups. The underlying premise of the education system is to provide the conditions for everyone to pursue the American Dream. There again, there is a conflict of values as it applies to Higher Education. The American Dream postulates that every American has the equal opportunity to attain success. But contrary to this belief, Higher Education has a history of racial and class-based exclusion according to John Thelin, who has written a comprehensive history of Higher Education. Similar to hiring and prompting Higher Education academic staff, acceptance to college is not merely about merit, but may seem alike a random decision from an outside perspective says Theliln. The most academically, hard-working students will not all be accepted to an Ivy League school.

When the Pew Economic Mobility Project conducted a survey , 39 % of respondents said they believed it was “common” for people born into poverty to become rich, and 71 % said that personal attributes like hard work and drive, not the circumstances of a person’s birth, are the key determinants of success. Yet Pew’s own research has demonstrated that it is exceedingly rare for Americans to go from rags to riches, and that more modest movement from the bottom of the economic ladder isn’t common either. In fact, economic mobility is greater in Canada, Denmark, and France than it is in the United States.

Full-time minimum wage workers cannot afford a two-bedroom rental anywhere in the U.S. and cannot afford a one-bedroom rental in 95% of U.S. counties, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s annual “Out of Reach” report.

In fact, the average minimum wage worker in the U.S. would need to work almost 97 hours per week to afford a fair market rate two-bedroom and 79 hours per week to afford a one-bedroom, NLIHC calculates. That’s well over two full-time jobs just to be able to afford a two-bedroom rental.

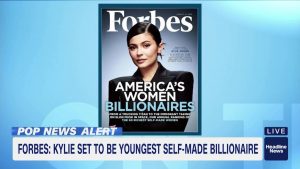

Each and every year Forbes magazine celebrates America’s billionaires as paragons of entrepreneurial success, asserting that the list “instills confidence that the American Dream is still very much alive.” Of the America’s current 400 richest, Forbes explains, 70% “made their fortunes entirely from scratch.” Most news media took that claim at face value and did little or no fact checking.

However, researchers at a Boston-based group, United for a Fair Economy, investigated the actual backgrounds of the Forbes 400. They concluded that most of the super rich were born with advantages, concluding Forbes was spinning a “misleading take of what it takes to become wealthy in America. Most of the Forbes 400 have benefited from a level of privilege unknown to the vast majority of Americans.” The study concluded that more than 60% of those on the list all grew up in substantial privilege with inheritances up to $1 million, and 11.5 of those on the list have inheritances well over $1 million. Seven per cent of those on the list had inherited wealth over $50 million.

Stephen McNamee and Robert Miller of the University of North Carolina, argue in their book, The Meritocracy Myth that there is a serious gap between how people think our economic system works and how it actually works. The authors cite data which shows that 20% of American households receive 50% of all available income and the lowest 20% of households receive less than 4%; the top 5% of households receive 22% of all available income; the richest 1% of households account for 30% of all available net worth. Economic inequality in the U.S. is the highest among all industrial countries.

The BBC reported startling economic equality figures in a recent documentary: the top 200 wealthiest people in the world control more wealth than the bottom 4 billion. But what is more striking to many is a close look at the economic inequality in the homeland of the “American Dream.” The United States is the most economically stratified society in the western world. As The Wall Street Journal reported, a recent study found that the top .01% or 14,000 American families hold 22.2% of wealth, and the bottom 90%, or over 133 million families, just 4% of the nation’s wealth.

The U.S. Census Bureau and the World Wealth Report 2010 both report increases for the top 5% of households even during the current recession. Based onInternal Revenue Service figures, the richest 1% have tripled their cut of America’s income pie in one generation. In 1980 the richest 1% of America took 1 of every 15 income dollars. Now they take 3 of every 15 income dollars.

The average American believes that the richest fifth own 59% of the wealth and that the bottom 40% own 9%. The reality is strikingly different. The top 20% of US households own more than 84% of the wealth, and the bottom 40% combine for a paltry 0.3%. The Walton family, for example, has more wealth than 42% of American families combined.

In a study published recently, Norton and Sorapop Kiatpongsan used a similar approach to assess perceptions of income inequality. They asked about 55,000 people from 40 countries to estimate how much corporate CEOs and unskilled workers earned. Then they asked people how much CEOs and workers should earn. The median American estimated that the CEO-to-worker pay-ratio was 30-to-1, and that ideally, it’d be 7-to-1. The reality? 354-to-1. Fifty years ago, it was 20-to-1.

Social Mobility

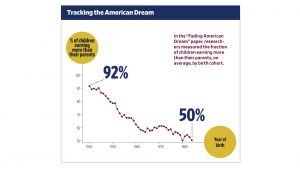

A Pew Foundation study, reported in the New York Times, concluded, “The chance that children of the poor or middle class will climb up the income ladder, has not changed significantly over the last three decades.” The Economist’s special report, “Inequality in America,” concluded, “The fruits of productivity gains have been skewed towards the highest earners and towards companies whose profits have reached record levels as a share of GDP.”

It is important to note that social class exerts a strong influence in the life of human beings. Socio-economic status may define how individuals think, how they act, the way people behave, the outfits individuals choose to wear, and furthermore, the use of language. Wealth tends to affect how one looks, where one eats, the stores one chooses to shop, the education one receives, and the occupations one may hold throughout life. In addition, it may also affect the person one chooses to love, the friends one has, the quality of one’s health, and above all it shapes the perspective individuals have of their own existence according to researcher Gary Newman.

In 2006, the Center for the Future of Children published the conclusions of a research that followed intergenerational socio-economic differences during the last 20 years. The study found that social mobility is high if the opportunity is open, but relatively low if the barriers associated with a person’s background are few. These obstacles can be defined as racial discrimination, poverty, or physical disability. A segment of the study focused on comparing occupations between individuals and their parents, with the premise that income is closely related to the prestige, nature, and rank of one’s work.

Several occupational shifts between generations were reported to illustrate this matter, with upward mobility occurring when individuals have a more prestigious and better paying job than that of their mother and father. Among men, 37 % were upwardly mobile and 32 % were downwardly mobile. Among women, on the other hand, 46 % were upwardly mobile, and 28 % felt into lower socio-economic strata, The latter and the former statistics result from a comparison between the jobs of current working individuals and those of their parents between 1988 and 2004.

In the same way, an editorial of the St. Louis Post Dispatch argues that in ‘in America, you can start poor, work hard and end up rich. But winding up rich is becoming more and more and more difficult unless you are born to wealthy parents.” Based upon a study by the Treasury Department, in which tax returns from the same groups were followed between 1996 and 2005, the editorial stated: “It was found that 45 % percent of the people in the poorest group managed to work their way out of it over the decade. Ten percent of them managed to make it to the middle class, and the incomes of 3.6 percent of them were among the highest 20 % of the country. Rags-to-riches still happen in America. But it’s notable that more than half the people who started out poor were still poor nine years later. Of those who started in the middle income, about a third stayed there. The rest were split pretty evenly between those who climbed higher and those who slipped down. By contrast, there was a startling difference among those who began well-off, a population that tends to stay that way. More than 85 % of those who started out in America’s richest quintile were still there a decade later. Economic status at the time of a person’s birth still makes a big difference.”

Despite current trends of social mobility, some sectors of society have shown a much more aristocratic nature. A self perpetuating political elite, for instance, is beginning to control the higher spheres of financial and governmental power, both in the Democrat and Republican parties. As the grandson of a senator, George W. Bush is not only the son of a president, but is also a member of wealthy business elite. John Kerry, on the other hand, married a very wealthy women after receiving his education at a Boston posh private school, and subsequently Yale. There, and just like the Bushes, Kerry belonged to the ultra-select Skull and Bones society. Al Gore is a Harvard graduate whose father was a senator, while John McCain’s grandfather and father were the first pair of father/son Four-Star admirals in the United States Navy. Historically, Barack Obama is one of the first serious candidates without blue-blood pedigree, who is also a member of an ethnic minority.

In addition, the self perpetuating political elite of the United States has found limited questionings. An article published in The Economist argues that if such a thing were to happen in England, if all the prime ministers were to come from Ethan and Harrow, Britain would be in high Dungeon. According to the journal, there is an increasing tendency for elites to self perpetuate. America is increasingly looking like imperial Britain, with dynastic ties proliferating, social circles interlocking, mechanisms of social exclusion strengthening, and a gap widening between those make decisions, shape culture, and the vast majority of those who work ordinary shifts from nine to five.

Some of the wealthiest entrepreneurs in North America say there is no such thing as the “self-made man.” With more millionaires making, rather than inheriting, their wealth, there is a false belief that they made it on their own without help, a new report published by the Boston-based non-profit United For a Fair Economy, states. The group has signed more than 2,200 millionaires and billionaires to a petition to reform and keep the U.S. inheritance tax. The report says the myth of “self-made wealth is potentially destructive to the very infrastructure that enables wealth creation.”

The individuals profiled in the report believed they prospered in large part to things beyond their control and because of the support of others. Warren Buffet, the second richest man in the world said, “I personally think that society is responsible for a very significant percentage of what I’ve earned.” Erick Schmidt,of Google says, “Lots of people who are smart and work hard and play by the rules don’t have a fraction of what I have. I realize that I don’t have my wealth because I’m so brilliant.”

Malcolm Gladwell, in his book, The Outliers, attacks America’s myth of the self-made man. Gladwell’s meticulous research has shown that enormously successful people like Bill Gates, The Beatles, and professional athletes, scientists and artists, all had people in their lives who helped them get there.

McNamee and Miller also challenge the idea that moral character and integrity are important for economic success. There is little evidence that being honest results in economic success. In fact, the reverse is true, as seen in the examples of Enron, WorldCom, Arthur Anderson and the Wall Street debacle. White collar crime in the form of insider trading, embezzlement, tax and insurance fraud is hardly a reflection of integrity and honesty. Playing by the rules probably works to suppress prospects for economic success, compared to those who ignore the rules.

In looking at jobs, we tend to focus on the “supply” side of the labor markets–the pool of available talent. Much less attention is spent on the demand side. For the past 20 years the “growth jobs” have been disproportionately in the low wage sector in entry-level jobs. At the same time, increasing numbers of people are getting advanced education, with insufficient numbers of high-powered jobs to accommodate them.

Income inequality has increased significantly in the U.S. during the current recession, perhaps more than at any time in recent history, a trend that may have significant damaging effects on the economy and social fabric.

British epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, authors of The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger, argue that almost every indicator of social health in wealthy societies is related to its level of economic equality. The authors, using data from the U.S. and other developed nations, contend that GDP and overall wealth are less significant that the gap between the rich and the poor, which is the worst in the U.S. among developed nations. “In more unequal societies, people are more out for themselves, their involvement in community life drops away,” Wilkinson says. If you live in a state or country where level of income is more equal, “you will be less likely to have mental illness and other social problems,” he argues.

A University of Leicester psychologist, Adrian White, has produced the first ever “world map of happiness,” based on over 100 studies of more than 80,000 people and by analyzing data from the CIA, UNESCO, The New Economics Foundation, the World Health Organization and European databases. The well being index that was produced was based on the prediction variables of health, wealth and education. According to this study, Denmark was ranked first, Switzerland second, Canada 10thand the U.S. 23rd.

A study published in Psychological Science by Mike Morrison, Louis Tay and Ed Diener, which is based on the Gallup World Poll of 128 countries and 130,000 people, found that the more satisfied people are with their country, the better the feel about themselves. Recent surveys in the U.S. show a significant percentage of Americans who are unhappy about their country. According to the World Values Survey of over 80 countries, the U.S. ranks only 16th, behind such countries such as Switzerland, the Netherlands, Sweden and Canada, with Denmark ranked first.

How The Self-Help Industry Perpetuates the Myths

Also, so many self-help gurus help to perpetuate the myths discussed here by convincing their clients that anyone can make it to the top with hard work and a few positive affirmations. These naive and damaging practices–particularly for young people–just reinforce and sustain the myth of the self-made man and meritocracy, and avoid dealing with the real problem of income inequality.

Our self-help culture doesn’t allow us to admit we might not be able to overcome greater economic woes on our own. In fact, it often makes our individual situations worse when things don’t work out.

Thomas Scheff, a professor emeritus at the University of California, Santa Barbara, recently published a paper in the journal Cultural Sociology claiming that in highly individualistic cultures like the United States, where people are encouraged to “go it alone,” shame is the price we pay for not achieving success.

Viewed through this prism, you can think of the constant simmering anger in our culture as the road rage of self-help culture. Fearing the humiliation of failure, we aggressively lash out at others who prove the self-help nostrums a lie.

This could be the reason that many, including Republican members of Congress, blame the long-term jobless for their own plight, and cut off their unemployment checks. We say those who fell prey to predatory lending weren’t misled, but were greedy.

According to the tenets of self-help, the victims of the American economic collapse need not a helping hand, but a kick in the pants. True, self-help advice is not always fully useless. Saving money, for starters, is certainly more likely to lead to a prosperous life than not putting anything aside at all. Yet all too often, knowledge and individual action are not enough. Self-help causes us to take the political and economic problem of increasing income inequality and make it personal. That’s both morally wrong and financially ineffective.

Former Governor of California, actor and bodybuilder Arnold Schwarzenegger, who made the commencement address at the University of Houston , told students that community is crucial and that there is no such thing as a “self-made man.” The concept, he said, “is a myth.” The former host of NBC’s “The Celebrity Apprentice” said that he wouldn’t be where he is without the help of many other people, including “my parents, my mentors, my teachers.”

The recent Forbes cover story calling Kylie Kardasian’s near billionaire status “self-made” sounds a lot like Donald Trump essentially classifying his beginnings in Brooklyn as humble, with a “small loan of a million dollars” from his dad.

The truth of the matter is:

- Virtually all entrepreneurs and business leaders rely on support from the government. Maybe they were educated at public schools and universities, or their companies rely on public infrastructure like roads and airports, or they were able to protect their big ideas through copyright and intellectual property laws. Or maybe they benefit from the lack of taxes on their income or assets.

- Companies like Kylie’s employ workers, either directly or through contracts and consultants, that make the products possible. Think about the people who assemble her lip kits or manufacture the makeup. They helped build her $900 million, but they likely haven’t seen as much of the profits.

- Consider arbitrary advantages, like luck and timing, or unearned advantages, such as gender and race privilege. It’s no accident that 76% of millionaires in the U.S. are white, and about 88% of billionaires in the world are men. Women and people of color encounter systemic discrimination when accessing things like loans, housing, and jobs, and communities of color have fewer resources to transfer intergenerationally due to the legacies of slavery, mass incarceration, and stolen Native land, among other things.

- Also, let’s be real, wealthy people, especially us white ones, profit off the ideas and cultures of other people — Kylie and the Kardashians, for example,have been accused of profiting off of black culture and copying black designers.

All of these truths point to the existence of a “built-together reality” as put by Brian Miller and Mike Lapham in their book The Self-Made Myth: And the Truth about How Government Helps Individuals and Businesses Succeed.

In their research Shai Davidai and Thomas Gilovich that suggest indifference lies in a distinctly American cultural optimism. At the core of the American Dream is the belief that anyone who works hard can move up economically regardless of his or her social circumstances. Davidai and Gilovich wanted to know whether people had a realistic sense of economic mobility.

The researchers found Americans overestimate the amount of upward social mobility that exists in society. They asked some 3,000 people to guess the chance that someone born to a family in the poorest 20% ends up as an adult in the richer quintiles. Sure enough, people think that moving up is significantly more likely than it is in reality. Interestingly, poorer and politically conservative participants thought that there is more mobility than richer and liberal participants.

How Beliefs in Meritocracy and Democracy Have Merged

Democracy, arguably in its most ideal sense, champions a presupposed equality of persons, while meritocracy is a justification for social inequality. In common parlance, they often are used synonymously or in close association with the even more diffuse ideas of equality, fairness, justice, liberty, etc. Furthermore, some would argue that democracy and meritocracy are interpenetrating concepts even as democracy broadly refers to “rule by the people,” or majority consent, whereas meritocracy can be described as rule by a deserving elite.

Conflations between democracy and meritocracy are related to their idealized aspirations for a more just society and the rejection of arbitrary domination by aristocracy or birth and inheritance. Both democracy and meritocracy appeal to the potential ennobling of the person according to one’s individual ability, effort and virtue, as well as the collective liberties and protections.

Michael Young examined the harsh side effects of meritocracy. For some, there is the erosion of the sense of self-worth for those at the bottom of society, as de nied by the individual. When these people believe that their current status in society is due to their lack of talent or hard work, they blame themselves. “They can easily become demoralized by being looked down on so woundingly by people who have done well for themselves … No underclass has ever been left as morally naked as that” .

Summary:

An estimated 34% to 45% of wealth in the U.S. is inherited, according to a 2005 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, and intergenerational class mobility is notoriously difficult, depending on where you grew up and what your racial identity is. The “self-made” story isn’t just wrong — it’s dangerous and discourages action to challenge the seemingly inevitable status quo.

There are more than 11 million millennials living in households with incomes of $100,000 or higher annually, and Gen Y will soon begin to inherit $30 trillion from their parents and grandparents over the coming decades. And this is all happening during an era of unprecedented wealth inequality — the richest 10% of Americans now own 76% of U.S. wealth and the number is increasing every year.

The enduring widespread beliefs in the “self-made man,” meritocracy and the American Dream—even among the lower socio-economic class—is doing a great in-service to the American people, and ones that prevent the country from addressing the serious pervasive problems of economic inequality and lack of social mobility.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book:Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.