Leaders are concerned with declining productivity, employee job satisfaction, and attracting and keeping the best workers. Issues related to motivation seem to be at the heart of these concerns, and worth revisiting.

What Do We Mean by Motivation?

The dictionary defines motivation as a stimulus, or influence, incentive, inspiration, inducement, incitement, spur, or reason. In the context of the workplace it can be viewed as “Internal and external factors that stimulate desire and energy in people to be continually interested and committed to a job, role or subject, or to make an effort to attain a goal. Motivation results from the interaction of both conscious and unconscious factors such as the (1) intensity of desire or need, (2) incentive or reward value of the goal, and (3) expectations of the individual and of his or her peers.”

We continue to revisit the issue of motivation and specifically, the “carrot and stick” aspect. New research seems to indicate that brain chemicals may control behavior and for people to learn and adapt in the world; therefore, both punishment and reward may be necessary. This conclusion would certainly run counter to the trend towards positive motivation without extrinsic reward or punishment.

When Employees are Not Motivated

According to Gallup, 87 percent of the global workforce is disengaged. Almost half of people are dissatisfied with their direct supervisors.A recent study by Aon Hewitt has revealed that employee engagement dipped for the first time since 2012. The 2017 Trends in Global Employee Engagement Report, which covered more than five million employees at over 1,000 organizations around the world, showed that less than one quarter of employees are highly engaged and 39% are moderately engaged. In a single year, employee engagement globally dropped from 65% in 2015 to 63% in 2016.

Despite employee engagement being a theme in leadership and management for more than twenty years, engagement levels are at an all time low and falling further.

Employee engagement as a term has been around since the early 90s. Before that it was employee satisfaction and then employee commitment in the 70s and 80s. The change in leadership and management circles to “engagement” followed a recognition that it wasn’t just about the employee. Employee engagement requires a two-way commitment and inter-dependence. Employee engagement has various definitions but usually involves commitment to the goals of the company and a willingness to go the extra mile to achieve them.

According to Gallup’s State of the American Workplace report, the majority of employees are not engaged and haven’t been for a long time. In 2016, only 33% of employees in the United States were engaged, and employee engagement as a whole increased only 3% from 2012-2016. These findings underscore the impact that employee engagement has when it comes to the overall success of U.S. organizations. In fact, in the first iteration of the Gallup report, Gallup found that disengaged employees cost the country somewhere between $450 and $550 billion each year.

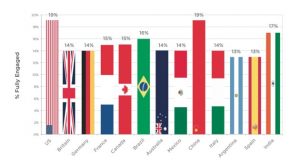

Percentage of Workers Considered “Engaged,” by Country

In the U.S., the survey found that a key indicator of engagement was whether employees were onboard with the mission of the company. In the U.K. and India, it was about whether employees valued being around coworkers who shared their values. In France, Canada, Brazil, and Argentina, workers responded most strongly to the statement “My teammates have my back.”

The survey, The 7 Key Trends Impacting Today’s Workplace, was conducted by the employee engagement firm TINYpulse, and involved over 200,000 employees in more than 500 organizations.

As the survey title suggests, the research explored a number of different management topics (culture, recognition, growth opportunities, etc.), but the issue that most interested me was the one surrounding motivation, as getting employees to give maximum effort is a challenge that has bedeviled managers for, well, as long as there have been managers.

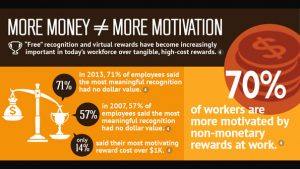

The specific question the survey asked was: “What motivates you to excel and go the extra mile at your organization?” Employees could choose from 10 answers. Interestingly, money – often simply assumed to be the major motivator – was seventh on the list, well back in the pack. The results were as follows:

- Camaraderie, peer motivation (20%)

- Intrinsic desire to a good job (17%)

- Feeling encouraged and recognized (13%)

- Having a real impact (10%)

- Growing professionally (8%)

- Meeting client/customer needs (8%)

- Money and benefits (7%)

- Positive supervisor/senior management (4%)

- Believe in the company/product (4%)

- Other (9%)

Obviously there is a clear link between levels of employee engagement in their work and the motivation to do work, and productivity.

So what accounts for a person being motivated? There are several theories.

Theories of Motivation

William James created a list of human instincts that included such things as attachment, play, shame, anger, fear, shyness, modesty, and love. The main problem with this theory is that it did not really explain behavior, it just described it.

By the 1920s, instinct theories were pushed aside in favor of other motivational theories, but contemporary evolutionary psychologists still study the influence of genetics and heredity on human behavior.

The incentive theory suggests that people are motivated to do things because of external rewards. For example, you might be motivated to go to work each day for the monetary reward of being paid. Behavioral learning concepts such as association and reinforcement play an important role in this theory of motivation. This theory shares some similarities with the behaviorist concept of operant conditioning. In operant conditioning, behaviors are learned by forming associations with outcomes. Reinforcement strengthens a behavior while punishment weakens it. While incentive theory is similar, it instead proposes that people intentionally pursue certain courses of action in order to gain rewards. The greater the perceived rewards, the more strongly people are motivated to pursue those reinforcements.

According to the drive theory of motivation, people are motivated to take certain actions in order to reduce the internal tension that is caused by unmet needs. For example, you might be motivated to drink a glass of water in order to reduce the internal state of thirst. This theory is useful in explaining behaviors that have a strong biological component, such as hunger or thirst. The problem with the drive theory of motivation is that these behaviors are not always motivated purely by physiological needs. For example, people often eat even when they are not really hungry.

The arousal theory of motivation suggests that people take certain actions to either decrease or increase levels of arousal. When arousal levels get too low, for example, a person might watch an exciting movie or go for a jog. When arousal levels get too high, on the other hand, a person would probably look for ways to relax such as meditating or reading a book. According to this theory, we are motivated to maintain an optimal level of arousal, although this level can vary based on the individual or the situation.

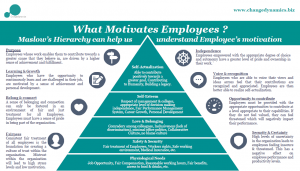

Humanistic theories of motivation are based on the idea that people also have strong cognitive reasons to perform various actions. This is famously illustrated in Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which presents different motivations at different levels. First, people are motivated to fulfill basic biological needs for food and shelter, as well as those of safety, love, and esteem. Once the lower level needs have been met, the primary motivator becomes the need for self-actualization, or the desire to fulfill one’s individual potential.

The expectancy theory of motivation suggests that when we are thinking about the future, we formulate different expectations about what we think will happen. When we predict that there will most likely be a positive outcome, we believe that we are able to make that possible future a reality. This leads people to feel more motivated to pursue those likely outcomes. The theory proposes that motivations consist of three key elements: valence, instrumentality, and expectancy. Valence refers to the value people place on the potential outcome. Things that seem unlikely to produce personal benefit have a low valence, while those that offer immediate personal rewards have a higher valence. Instrumentality refers to whether people believe that they have a role to play in the predicted outcome. If the event seems random or outside of the individual’s control, people will feel less motivated to pursue that course of action. If the individual plays a major role in the success of the endeavor, however, people will feel more instrumental in the process. Expectancy is the belief that one has the capabilities to produce the outcome. If people feel like they lack the skills or knowledge to achieve the desired outcome, they will be less motivated to try. People who feel capable, on the other hand, will be more likely to try to reach that goal.

While no single theory can adequately explain all human motivation, looking at the individual theories can offer a greater understanding of the forces that cause us to take action. In reality, there are likely many different forces that interact to motivate behavior.

Incentive theory began to emerge during the 1940s and 1950s, building on the earlier drive theories established by psychologists such as Clark Hull. How exactly does this theory account for human behaviors? Rather than focus on more intrinsic forces behind motivation, the incentive theory proposes that people are pulled toward behaviors that lead to rewards and pushed away from actions that might lead to negative consequences. Two people may act in different ways in the same situation based entirely on the types of incentives that are available to them at that time.

You can probably think of many different situations where your behavior was directly influenced by the promise of a reward or punishment. Perhaps you studied for an exam in order to get a good grade, ran a marathon in order to receive recognition, or took a new position at work in order to get a raise. All of these actions were influenced by an incentive to gain something in return for your efforts.

Rewards or Punishment (the “Carrot or the Stick?”)

The Carrot and Stick Approach of Motivation is a traditional motivation theory that asserts, in motivating people to elicit desired behaviors, sometimes the rewards are given in the form of money, promotion, and any other financial or non-financial benefits and sometimes the punishments are exerted to push an individual towards the desired behavior.

The Carrot and Stick approach of motivation is based on the principles of reinforcement and is given by a philosopher Jeremy Bentham, during the industrial revolution. This theory is derived from the old story of a donkey, the best way to move him is to put a carrot in front of him and jab him with a stick from behind. The carrot is a reward for moving while the stick is the punishment for not moving and hence making him move forcefully.

In the September 27, 2017 Harvard Business Review, Tali Sharot, an associate professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at the University College London, shares how the reward of praise was more effective to increase hospital employees’ hand sanitizing efforts than the threat of disease (and obvious punishment). In fact, cameras monitoring employees washing or not washing their hands showed an increase from 10% compliance when warning signs about disease were used to motivate employees’ actions versus almost 90% compliance when an electronic board displayed a positive message (“Good job!”) to reward hand washing. Bottom line: immediate positive feedback is very effective when it comes to changing actions. Sharot explains that our brains have evolved over time to be wired such that we think “if reward, then action needed.”

On the flip side, our brains have also evolved to avoid negative consequences (such as drowning, poison, or dangerous areas) by inaction or staying where we are. Most people have experienced the phenomena of freezing in place in a potentially dangerous situation. Sharot believes that “when we anticipate something bad, our brain triggers a ‘no go’ signal.” For this reason, punishments (like getting fired or being legally prosecuted) may be most effective to discourage people from acting in certain ways (like stealing from the company or sharing trade secrets).

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Motivation

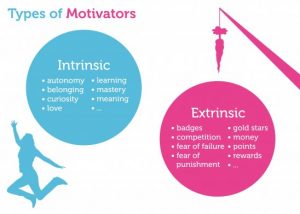

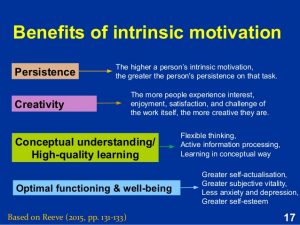

So, the primary difference between the two types of motivation is that extrinsic motivation arises from outside of the individual while intrinsic motivation arises from within. Researchers have also found that the two type of motivation can differ in how effective they are at driving behavior.

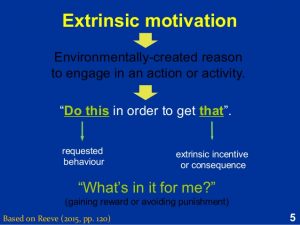

Extrinsic motivation occurs when we are motivated to perform a behavior or engage in an activity to earn a reward or avoid punishment. People are engaging in a behavior not because they enjoy it or because they find it satisfying, but in order to get something in return or avoid something unpleasant.

Some studies have demonstrated that offering excessive external rewards for an already internally rewarding behavior can lead to a reduction in intrinsic motivation, a phenomenon known as the overjustification effect. In one study, for example, children who were rewarded for playing with a toy they had already expressed interest in playing with became less interested in the item after being externally rewarded.

This is not to suggest that extrinsic motivation is a bad thing. Extrinsic motivation can be beneficial in some situations. It can be particularly helpful in situations where a person needs to complete a task that they find unpleasant. However:

Extrinsic rewards can be used to motivate people to acquire new skills or knowledge. Once these early skills have been learned, people may then become more intrinsically motivated to pursue the activity. External rewards can also be a source of feedback, allowing people to know when their performance has achieved a standard deserving of reinforcement.

Intrinsic motivation involves engaging in a behavior because it is personally rewarding; essentially, performing an activity for its own sake rather than the desire for some external reward. The person’s behavior is motivated by an internal desire to participate in an activity for its own sake. Essentially, the behavior itself is its own reward.

Can you influence or even change a person’s behavior through conditioning? The real question is, which route would you choose—positive or negative? Most people are taught to refrain from engaging in a certain behavior by being given punishments that create negative feelings. This helps maintain discipline at home, school and even organizations. However, it has long been debated as to which one works better on behavior.

Are there genetic and brain chemistry factors that could influence our perspective on this issue?

Hanneke den Ouden and Roshan Cools and their colleagues from the Donders Institute in Nijmegen and New York University have published their research in the journal Neuron. They concluded brain chemicals serotonin and dopamine-related genes influence how we base our choices on past punishments or rewards. This influence depends on which gene variant you inherited from your parents. Den Ouden explains: “We used a simple computer game to test the genetic influence of the genes DAT1 andSERT, as these genes influence dopamine and serotonin. We discovered that the dopamine gene affects how we learn from the long-term consequences of our choices, while the serotonin gene affects our choices in the short term.”

Den Ouden goes on to say “Different players use different strategies. It all depends on their genetic material. People’s tendency to change their choice immediately after receiving a punishment depends on which serotonin gene variant they inherited from their parents. The dopamine gene variant, on the other hand, exerts influence on whether people can stop themselves making the choice that was previously rewarded, but no longer is.”

What Motivates Employees to Be More Engaged and Productive?

It turns out that people are motivated by interesting work, challenge, and increasing responsibility—intrinsic factors. People have a deep-seated need for growth and achievement. Herzberg’s work influenced a generation of scholars and researchers—but never seemed to make an impact on managers in the workplace, where the focus on motivation remained the “carrot-and-stick” approach, or external motivators.

A review of the research literature by James R. Lindner at Ohio State University concluded that employee motivation was driven more by factors such as interesting work than financial compensation. John Baldoni, author of Great Motivation Secrets of Great Leaders, concluded that motivation comes from wanting to do something of one’s own free will, and that motivation is simply leadership behavior—wanting to do what is right for people and the organization.

The survey, The 7 Key Trends Impacting Today’s Workplace, was conducted by the employee engagement firm TINYpulse, and involved over 200,000 employees in more than 500 organizations.

As the survey title suggests, the research explored a number of different management topics (culture, recognition, growth opportunities, etc.), but the issue that most interested me was the one surrounding motivation, as getting employees to give maximum effort is a challenge that has bedeviled managers for, well, as long as there have been managers.

The specific question the survey asked was: “What motivates you to excel and go the extra mile at your organization?” Employees could choose from 10 answers. Interestingly, money – often simply assumed to be the major motivator – was seventh on the list, well back in the pack. The results were as follows:

- Camaraderie, peer motivation (20%)

- Intrinsic desire to a good job (17%

- Feeling encouraged and recognized (13%

- Having a real impact (10%)

- Growing professionally (8%

- Meeting client/customer needs (8%)

In his book, Drive, Daniel Pink, describes what he says is “the surprising truth” about what motivates us. Pink concludes that extrinsic motivators work only in a surprisingly narrow band of circumstances; rewards often destroy creativity and employee performance; and the secret to high performance isn’t reward and punishment but that unseen intrinsic drive—the drive to do something because it is meaningful. Pink says that true motivation boils down to three elements: Autonomy, the desire to direct our own lives; mastery, the desire to continually improve at something that matters to us, and purpose, the desire to do things in service of something larger than ourselves. Pink, joining a chorus of many others, warns that the traditional “command-and-control” management methods in which organizations use money as a contingent reward for a task, are not only ineffective as motivators, but are actually harmful.

Nitin Nohria, Boris Groysberg and Linda-Eling Lee writing in the Harvard Business Review, describe a new model of employee motivation. They outline the four fundamental emotional drives that underlie motivation as: The drive to acquire (the acquisition of scarce material things, including financial compensation, to feel better); the drive to bond (developing strong bonds of love, caring and belonging); the drive to comprehend (to make sense of our world so we can take the right actions); and the drive to defend (defending our property, ourselves and our accomplishments).

Norhria and associates argue that managers who try to increase motivation must satisfy all of these four drives. Best practice companies have initiated reward systems based on performance. They have addressed the bond drive by developing a corporate culture based on friendship, mutual reliance, collaboration and sharing; addressed the drive of comprehend by instituting job design system where jobs are designed for specific roles, and they have attempted to create jobs are meaningful and foster a sense of contribution to the organization. And finally to address the defend drive, best practice companies restructure their leadership approaches to increase transparency of all processes, ensure fairness throughout the organization and build trust and openness with everyone.

Financial Rewards Can Motivate–With Limitations

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, writing in Harvard Business Review, says “Intuitively, one would think that higher pay should produce better results, but scientific evidence indicates that the link between compensation, motivation and performance is much more complex. In fact, research suggests that even if we let people decide how much they should earn, they would probably not enjoy their job more.”

Propelling teams forward is a basic leadership task. But people’s perception of their chances of success and willingness to exert energy change as they get closer to reaching their goals, research shows. Leaders who understand this are able to modify their motivational techniques over time to carry employees across the finish line.

According to Olya Bullard, a professor at University of Winnipeg. In North America and some other regions, people are generally more susceptible to positive reinforcement. Applauding incremental success works well in the early stages of an effort with a set goal, says Bullard. That is when people assess their performance based on how far they’ve progressed from zero, the point at which they began. They are motivated by every step that moves them forward.

But as people pass the midpoint toward their goals, something happens, says Bullard, who conducted her research with Rajesh V. Manchanda of the University of Manitoba. They stop focusing on how far they have come and start focusing on how far they have yet to go. The prevention system kicks in. As people contemplate their distance from the end point, they concentrate more on the chances they won’t reach it and the negative consequences if they fail to do so.

At that point, Bullard says, leaders should shift their motivational approach to align with employees’ changed focus. Rather than applaud doing things right, leaders should urge people not to start doing things wrong. “In the beginning you might tell the team to start cold calling people and win business,” says Bullard. “Toward the end, you would say, ‘Don’t stop cold-calling people! Don’t miss out on that sale!” The leader’s style of motivation “should not be either/or,” says Bullard. “People change how they see the goal. So [the approach to motivation] should change too.”

Another motivation challenge emerges when employees pursue not some quantitative goal but rather triumph over a rival. In those circumstances, people assess their positions against a moving target. The danger becomes complacency.

In the early stages of competition, just believing that winning is feasible has the most important influence on motivation, says Jordan Etkin, a professor of marketing at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business. (Stanford’s Szu-Chi Huang and Fudan University’s Liyin Jin co-authored the study. So staying ahead helps. Every investment or sale your company lands at the expense of a competitor is new evidence that you can actually win this thing. That validation is especially important for startup teams, who may still question the decision to leave secure employment.

Winning feels great, of course. But always winning dulls your motivation, and that can hurt you. “If you are ahead you can lose that scrappiness,” says Etkin. “You may slack off a little bit.” The optimal position is to be a little bit behind. “That is a highly motivating state because you want to catch up,” says Etkin.

Obviously leaders don’t want their teams stalled in second place just so they’ll be eternally hungry. So by all means encourage outright wins and–when they occur– give people brief periods to relish their triumph. That helps sustain high performance.

However, “it becomes a little bit of a game how long to sit back and enjoy being on top without potentially doing damage to future performance,” says Etkin. So always have that next rabbit lined up and ready to chase. “Yes, we beat this company,” says Etkin. “But those guys over there are a little bit better than we are.”

“When we think about how people work, the naïve intuition we have is that people are like rats in a maze,” says behavioral economist Dan Ariely (TED Talk: What makes us feel good about our work?) “We really have this incredibly simplistic view of why people work and what the labor market looks like.” Instead, when you look carefully at the way people work, he says, you find out there’s a lot more at play — and at stake — than money. Ariely provides evidence that we are also driven by the meaningfulness of our work, by others’ acknowledgement — and by the amount of effort we’ve put in: the harder the task is, the prouder we are.

“When we think about labor, we usually think about motivation and payment as the same thing, but the reality is that we should probably add all kinds of things to it: meaning, creation, challenges, ownership, identity, pride, etc.,” Ariely says.

Edwin Locke, Ph.D., who is the Dean’s Professor Emeritus of Leadership and Motivation at the R.H. Smith School of Business at the University of Maryland. Locke compared four methods of motivating employee performance: money, goal setting, participation in decision making, and redesigning jobs to give workers more challenge and responsibility. He found that the average improvement in performance from money was 30%, compared to an increase in performance by 16% for goal setting, less than one percent improvement from participation in decision making, and a 17% improvement from job redesign. In addition, Locke reviewed numerous motivation studies and found that when money was used as a method of motivation it always resulted in some improvement in employee performance.

It is clear that money is a motivator of employee productivity. However, like the relationship between children’s viewing of violent television content and aggressive behavior, the relationship is not a simple one. Money can motivate some people under some conditions. In order for money to motivate an employee’s performance four conditions must be met.

- Money must be important to the employee.

- The employee must perceive money as being a direct reward for performance.

- The employee must perceive the marginal amount of money offered for the performance as significant.

- Management must have the discretion to reward high performing employees with more money.

It is rare for all four of these conditions to be simultaneously met. Not all employees are motivated by money to increase performance. Employees who are intrinsically motivated are unlikely to be influenced by monetary incentives. In addition, money is likely to be a strong motivator for employees who are focused on meeting lower-order needs (basic needs critical to survival), but it is not likely to have the same affect on those who have all of their lower-order needs met. This is consistent with research by psychologists Ed Diener and Martin Seligman, as well as Daniel Kahneman and his colleagues, indicating that after people have the basic necessities of life, having more money does not increase happiness much at all.

As far as the second condition goes, pay increases are often determined by community pay standards, cost-of-living, and the organization’s current and future financial prospects rather than by each employee’s level of performance. In today’s economy, many employees are not getting raises and for those who are, the amount of increase taken home after taxes is not likely to be perceived as a significant reward for performance. Finally, managers often have only a small amount of discretion within which they can reward employees for higher performance. Thus, since it is unlikely that all of the conditions necessary to make money a motivator for higher performance will be met, it is unlikely that money can successfully be used to increase performance.

A study recently published in the Human Resources Management Journalrevealed that workers who receive performance-based pay, such as those whose pay ties into individual or company-wide performance, work harder, but also end up with higher stress levels and lower levels of job satisfaction.

The research found that employees who know that how much money they take home each year is tied to their level of contributions to the organization, or how well their employer as a whole performs financially, are more likely to feel that they are being encouraged to work too hard.

That pressure in turn offsets the gains in productivity that the pay structure is designed to produce, the study’s authors said.

Chidiebere Ogbonnaya, the study’s lead author and a research fellow at the University of East Anglia, said that, despite an increase in thinking among employers that performance-based pay structures are important for motivating employees and encouraging positive attitudes, this study is the first to find that these pay schemes are associated with feeling that work might be too demanding or that there is insufficient time to get work done.

“By tying employees’ performance to financial incentives, employers send signals to employees about their intention to reward extra work effort with more pay,” Ogbonnaya said in a statement. “Employees in turn receive these signals and feel obliged to work harder in exchange for more pay.”

Although employees may value these earnings and see the pay structure as a positive, the ultimate beneficiary of their extra effort is the organization. “As a consequence, performance-related pay may be considered exploitative, or a management strategy that increases both earnings and work intensification,” Ogbonnaya said.

When looking specifically at pay tied into employer profits, the researchers found that this pay structure only had a positive impact on job satisfaction, employee commitment and trust in management if the profit-related pay was distributed widely across the organization.

The study found that when profit-related pay was given only to a small proportion of the workforce, there was lower job satisfaction, lower employee commitment and lower trust in management.

After reviewing four similar studies of employee motivation conducted in 1946, 1980, 1986, and 1992, Carolyn Wiley, the Department Chair for Management, Leadership, & Human Resources at Roosevelt University, uncovered top responses such as “interesting work,” “job security,” “good wages,” and “feeling of being in on things.”

Yet over the 46 years of studies, only one answer was cited every time among the top two motivators…

“Full appreciation of work done.”

According to Wiley, “More than 80 percent of supervisors claim they frequently express appreciation to their subordinates, while less than 20 percent of the employees report that their supervisors express appreciation more than occasionally.”

It’s clear there is a recognition gap. And this gap is likely to widen as Generation Z enters the workforce with new appetites and expectations for how, when, and why managers deliver recognition.

In the past, the expectations surrounding recognition were yearly, quarterly, or at best, monthly–hence the popularity of “employee of the month” programs.

In fact, according to a new study by The Workforce Institute at Kronos and Future Workplace, 32 percent of Generation Z measure their success based on the recognition they receive from managers. Recognition from managers was Generation Z’s number two measure of success behind “respect from co-workers.”

Supportive managers should strive to communicate these three things when recognizing Generation Z employees:

- “I recognize your good work.

- “I value you”.

- “We’re going places together.”

Leadership Behavior and Motivation

In an age of accelerating change and the relentless market requirement for adaptation, “Command and Control” does not work. There’s too much power at the top, and an organization cannot move quickly enough. Team members’ creativity and problem solving ability is not engaged and decision-making bottlenecks are prevalent.

David Rock and Jeffrey Schwartz’s research into how breakthroughs can be applied to make organizational transformation succeed show that:

- Behaviorism does not work—the carrot and the stick (rewards and punishments) approach may work for a short time but it does not yield the intrinsic motivation that creates innovation and long term sustainable results. The carrot raises the anxiety level for non-performers (creates Critter State), while people who are already performing are not stretched. The stick focuses attention on behaviors that don’t work and on the situations that preceded them.

- Even humanism is proving to not work very well. When managers are “too nice,” too personally involved with the problems of their people the leader often falls into the Rescuer role in the Tension Triangle. This ultimately disempowers people. Like the carrot and the stick approach, it also focuses too much attention on what is wrong rather than on how to solve the problem.

Emma Seppala, writing in Harvard Business Review, argues Studies show that people who have a sense of purpose are more focused, creative, and resilient, so leaders should make a point of reminding employees how their work is improving people’s lives. Distributing client or customer testimonials and announcing when corporate profits are donated to charities are just a couple of examples of how to do so. Research from Wharton’s Adam Grant shows that even unsatisfied employees feel better about their jobs when they devote time to good causes, and that workplace support programs are effective not only because people get help, but also because they can give it. Leaders, too, can be great sources of inspiration to employees.

Studies show that when they act selflessly, proving they care more about the group than themselves, workers are more trusting, cooperative, dedicated, loyal, collegial, and committed. Bosses who show they are fair also inspire greater dedication, citizenship, and productivity, as Wayne Baker of the University of Michigan has shown. Make sure to work alongside your team members on a daily or weekly basis, showing your allegiance to them and to the broader organization.

Seppala suggests leaders demonstrate these behaviors to motivate employees:

- Inspiration Through Meaning. Studies show that people who have a sense of purpose are more focused, creative, and resilient, so leaders should make a point of reminding employees how their work is improving people’s lives. Distributing client or customer testimonials and announcing when corporate profits are donated to charities are just a couple of examples of how to do so. Research from Wharton’s Adam Grant shows that workplace support programs are effective not only because people get help, but also because they can give Leaders, too, can be great sources of inspiration to employees.

- Acting Selflessly. Studies show that when they act selflessly, proving they care more about the group than themselves, workers are more trusting, cooperative, dedicated, loyal, collegial, and committed. Bosses who show they are fair also inspire greater dedication, citizenship, and productivity, as Wayne Baker of the University of Michigan has shown. Make sure to work alongside your team members on a daily or weekly basis, showing your allegiance to them and to the broader organization.

- Demonstrating consideration and respect. The basics of a kind culture involve consideration and respect, which increase creative output at both the individual and team level, Kind leaders do small things to show they care about their staff as people, not just employees. Simply asking how someone is doing personally and really listening to their answer is a good first step.

- Practicing and Encouraging Self-Care. According to Sabine Sonnentag from the University of Konstanz in Germany, exercise, breaks from work, relaxation practices, and more strict boundaries between work and home can reduce job stress and increase employee well-being and engagement. You can also encourage people to take more care with a basic resource: sleep.

Summary:

The carrot-and-stick approach worked well for typical tasks of the early 20th century —routine, unchallenging and highly controlled. For these tasks, where the process is straightforward and lateral thinking is not required, rewards can provide a small motivational boost without any harmful side effects. But jobs in the 21st century have changed dramatically. They have become more complex, more interesting and more self-directed, and this is where the carrot-and-stick approach has become unstuck. In summary, the implications for managers in organizations are significant. Leaders today must be not just cognizant of the latest research on motivation, but take action to make those organizational and relationship changes to take advantage of this research. And care must be taken to simply conclude that our motivation is blindly driven by brain chemicals.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book:Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.