Leadership must be important. More than 20,000 books and thousands of articles have been written about the critical elements of leadership and the impact it makes on people, organizations and countries, if not the world.

Yet even today, despite the collective wisdom of centuries on this topic, confidence in our leaders is low and continues to decline. Seventy-seven percent of those polled nationwide in the U.S. say that the country now has a crisis in leadership and confidence levels have fallen to the lowest levels recorded in recent times.

Those are among the key findings of a nation-wide poll, in 2012, the National Leadership Index (NLI), released by the Center for Public Leadership at Harvard Kennedy School and Merriman River Group. The survey is the seventh annual measurement of public attitudes toward 13 different sectors of American life, ranging from business and non-profits to politics and religion. In only two sectors measured in the year’s report—military and medical—did the leaders receive above-average confidence scores. Ratings for the remaining eleven sectors fell into the below-average range or remained in the below-average range. Wall Street and Congress stood out as the sectors in which Americans have the least confidence—indeed, the confidence rating for these two was barely above “none at all.”

For years, organizations have lavished time and money on improving the capabilities of managers and on nurturing new leaders. US companies alone spend almost $14 billion annually on leadership development. Colleges and universities offer hundreds of degree courses on leadership, and the cost of customized leadership-development offerings from a top business school can reach $150,000 a person.

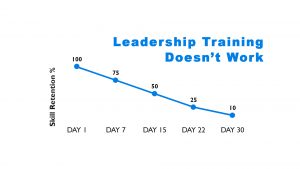

Michael Beer, Magnus Finnström, and Derek Schrader in their article “Why Leadership Training Fails—and What to Do about It.” Harvard Business Review, argue “U.S. corporations spend enormous amounts of money—some $456 billion globally in 2015 alone—on employee training and education, but they aren’t getting a good return on their investment. People soon revert to old ways of doing things, and company performance doesn’t improve.”

Cynthia Kivland and Natalie King of the University of Illinois, argue leadership development programs fail because:

- No Long-term measures prove the permanency of training. Companies require measures for their own performance, but don’t require measures on the permanency of their leadership training.

- Lack of management support. The extent to which new skills or behavior are reinforced by management is directly proportional to the adoption of these behaviors into the culture.

- Leaders don’t walk the talk. Organizations often believe that the degree of employee support and commitment to training is directly related to the amount of training dollars or how loud the leadership team champions a specific training program.

- The absence of pre-screening to measure the compatibility of the trainee to the training or the training to the culture Studies of the influence of trainees’ characteristics on training effectiveness have focused on the level of ability (Able) necessary to learn program content. Just as important are the motivational (Willingness) and environmental influences (Readiness) of the trainee and culture.

In a recently published media interview, Brigid Carroll, an associate professor at the University of Auckland School of Business rightly deplored what Harvard Business Review called “the great training robbery,” with billions squandered by business worldwide on ineffective leadership development programs.Carroll, author of a new book, Responsible Leadership: Realism and Romanticism, co-edited with British academic Steve Kempster, disparages what she deems the inadequacy of the traditional understanding of leadership, which she believes focuses on individual charismatic leadership. She prefers instead to see leadership as asking the big questions, like “sustainability, social responsibility, innovation, marketplace shifts, and inequality” and seeking solutions through “groups connecting and holding responsibilities.”

Leaders Continue to Fail

In the past two decades, 30% of Fortune 500 chief executives have lasted less than three years. Top executive failure rates as high as 75% and rarely less than 30%. Chief executives now are lasting 7.6 years on a global average down from 9.5 years in 1995. According to the Center for Creative Leadership, 38% new chief executives fail in their first 18 months on the job.

It appears the major reasons for failure has nothing to do with competence, or knowledge, or experience. Sydney Finkelstein, author of Why Smart Executives Fail, and David Dotlich and Peter C. Cairo, in their book,Why CEOs Fail: The 11 Behaviors That Can Derail Your Climb To The Top And How To Manage Them, present cogent reasons why chief executives fail, most of which have to do with hubris, ego and a lack of emotional intelligence.

In a provocative article in the Harvard Business Review Blogs, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, author of book is Confidence: Overcoming Low Self-Esteem, Insecurity, and Self-Doubt.argues more males fail as leaders than women: “The main reason for the uneven management sex ratio is our inability to discern between confidence and competence. That is, because we (people in general) commonly misinterpret displays of confidence as a sign of competence, we are fooled into believing that men are better leaders than women. In other words, when it comes to leadership, the only advantage that men have over women (e.g., from Argentina to Norway and the U.S. to Japan) is the fact that manifestations of hubris — often masked as charisma or charm — are commonly mistaken for leadership potential , and that these occur much more frequently in men than in women.

Chamorrow-Premuzic goes on to contend the paradoxical implication is that the same psychological characteristics that enable male managers to rise to the top of the corporate or political ladder are actually responsible for their downfall. In other words, what it takes to get the job is not just different from, but also the reverse of, what it takes to do the job well. As a result, too many incompetent people are promoted to management jobs, and promoted over more competent people.

Virtually anywhere in the world men tend to think that they that are much smarter than women, Chamorrow-Premuzic, argues, yet “arrogance and overconfidence are inversely related to leadership talent — the ability to build and maintain high-performing teams , and to inspire followers to set aside their selfish agendas in order to work for the common interest of the group. Indeed, whether in sports , politics or business, the best leaders are usually humble— and whether through nature or nurture, humility is a much more common feature in women than men. A study of all sectors and 40 countries, shows that men are consistently more arrogant, manipulative and risk-prone than women.” Unsurprisingly, the mythical image of a “leader” embodies many of the characteristics commonly found in personality disorders , such as narcissism and psychopathy as well as histrionic or Machiavellian personalities.

So why do we continue to have significant levels of leader failure when leadership development and training programs proliferate?

Part of the reason why leadership development programs fails is inextricably tied to our notions of what makes a good leader. Tasha Eurich, author of Bankable Leadership: Happy People, Bottom Line Results and the Power to Deliver Both argues “Though scientists spent most of the 19th century convinced that good leadership was inborn and fixed, the research of the early 20th century told a different story—that leadership is largely made. A recent study by Richard Arvey at Singapore’s NUS Business School revealed that up to 70 percent of leadership is learned. But business leaders are divided. The Center for Creative Leadership reports that 20 percent of C-level executives believe that leadership is born, and more than 28 percent believe it’s equally born and made. But, the evidence shows otherwise.”

According to a recent survey of 28,000 business leaders, conducted under the guidance of Chief Learning Officer magazine, leadership development is a high-touch, in-person effort that focuses on soft skills (as opposed to certification training, or skills-based instruction). 74% of organizations use instructor-led leadership training, and 63% use executive coaching, to deliver on the following top-rated leadership skills:

- Improving coaching skills (a priority for 34% of respondents)

- Communication (31%)

- Employee Engagement (27%)

- Strategic planning and business acumen (21%)

The soft skills of leadership are critical to advancing the organization (as well as advancing the careers of those who aim for the C-Suite).

According to an MIT study investment in leadership education and development approached $50 billion in the U.S. alone in the year 2000, and it has grown considerably since. Leadership training has become a big business, with publishers, universities and consultants jockeying to position themselves as the “go-to” partners and gurus to develop leaders.Despite these massive efforts, the picture of failed leadership persists, from the halls of government to the next startup. In particular, the track record of success for CEOs is not pretty. Research shows that most development programs fail to deliver expected returns.

The MIT study of dozens of companies over two decades identifies three “pathologies” that may account for leadership failures. The first is “the ownership is power mind-set.” Older ways of managing, predominantly a command and control style persist, and these ways collide with the new realities of what makes organizations and their employees behave, which requires a system of shared accountability and responsibility. The MIT study argues that ownership and control is the wrong issue and illustrates old-world thinking. Leaving responsibility solely to the CEO or management team or HR for developing leaders is not realistic and is not successful.

The second pathology identified in the MIT study is the “productization of leadership development,” or in other words, leadership development is linked to the products of the organization, rather than the overarching problems that need to be solved. Which often leads to quick fixes. This is frequently seen as a leadership program based on a best selling book or off-the-shelf leadership program purchased from a consultant. The result frequently ends up in the flavor of the month approach to training programs, which are often frequently forgotten in a short time. During tough economic times, top executives decide to curtail investments in leadership development, ushering in the return of a more Darwinian model of leadership — “the cream will rise to the top.” Employees then become cynical about the company’s dedication to leadership development. High-potentials hesitate before investing their energy in developmental initiatives; some of the best walk away from the organization, and others do not reach their potential for lack of strong developmental experiences. In this scenario, there are no winners.

The third pathology that the MIT study identifies is “make believe metrics.” Most organizations require accountability for their expenditures, which is often driven by metrics. Today there are scorecards for virtually everything, including leadership development. However, the MIT study concludes, the use of metrics for the effectiveness of leadership development is leading them astray. Most metrics don’t measure the soft skills, or strategic thinking or collaborative behavior, all of which are essential for leadership success. Organizations tend to measure the things that are easy to measure. “The philosophy that dominates so many company cultures today is that initiatives that cannot be measured have no value. In most instances, that is a reasonable assumption. But it does not apply to leadership development — not, at least, in the quantifiable terms that dictate assessments of capital expenditures,” the authors of the MIT study conclude.

My experience in two decades of experience as a CEO and senior executive coach convinces me that the focus on leadership development is in the wrong place. Most leadership development initiatives focus on competencies, skill development and techniques, which is some ways is like rearranging the deck chairs on a sinking ship. Good leaders need to become masters of themselves before they can attempt to be masters of anything else.

Leadership development initiatives need to focus on the following core areas to really make a difference in the type of leaders we have leading our organization:

- Self-awareness. Leadership development needs to be an inside-out process that focuses less on competencies and skill acquisition and more on increasing a leader’s self-awareness, and understanding how their behavior impacts others;

- Emotional self-mastery. Again, a superficial program of increasing emotional intelligence through techniques and tips of such things as listening skills, facilitation skills avoids or neglects the more important requirement of leaders to understand, manage and master their emotions and understand and respond appropriately to the emotions of others;

- A deep understanding of the dynamics of human behavior on an individual basis. I continue to be amazed at how many senior executives have a thorough knowledge of skill areas such as finance or marketing , but lack a modern understanding of the significant neuroscience, human performance and psychological research that have enormous implications for managing employees, customers and vendor relationships. Also, executives often make the mistake of implementing behavioral based training programs on one-size fits all basis, ignoring individual personality and motivational differences;

- Ongoing engagement. Leadership development initiatives are often a “one-time” effort organized around a book, a seminar or workshop, or a few coaching sessions, ignoring the fact that any substantial behavioral or attitudinal change requires continuity and a long-term commitment to be successful. Also, a focus on experiential learning, rather than cognitive and information driven skill acquisition is required;

- Good training design. Often, leadership development programs, by default, are designed and implemented by and HR executive or department or by a senior executive, neither of which have had in-depth training themselves in the latest developments in neuroscience, psychology and human performance, nor have they themselves gone through an intensive personal development process of self mastery;

- An individual personal stake in self-development. Leadership development is frequently seen as the responsibility of the organization rather than a shared responsibility with potential and current leaders. Rarely have I heard them say that they want to take personal responsibility to become the best person they can be and take charge of their personal growth;

- Confusion about leadership versus management. While there is some cross-over between the two, they are not the same. Management expertise often requires and emphasizes specific competencies and skills, whereas those things should not be the focus of leadership development;

- A organizational culture that values individual and collective personal growth as a priority. Most organizations value things—such as financial returns, marketing, product development, etc.–over people development. And during difficult economic times, the people development and well-being budgets are the first to be cut;

- Choosing people who know how to mentor, coach and develop leaders. The mistaken assumption is that individuals who are currently leaders in the organization or HR personnel by function are best suited to teach leadership, and coach and mentor leaders. This is like arguing that you are an educational expert if you went to school. Leadership development initiatives should be led by experts in teaching and learning and facilitation;

- Making a connection between leadership development and its application. It’s one thing to learn leadership theory and illustrative case studies. It’s another thing altogether to apply that to actual situations where the individuals are given an opportunity to grow and demonstrate their capacities;

- Incorporate mindfulness practices into leadership development. Good leaders are reflective and often introspective. The incorporation of mindfulness practices that emphasize those things would contribute greatly to a culture that balances “being” with “doing;

- Recruit potential leaders for development that are humble and not driven by hubris or ego. Organizations continue to recruit leaders who fit the traditional stereotype of a charismatic, narcissistic male leader, who have little humility and a big ego.

The solution to the problem of leadership development ineffectiveness lies in an integrated approach to the recruitment, shared responsibility for personal growth and the development of an organizational culture that sees leadership development as an organic process.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book:Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.