Driving, directive, coercive styles of leadership may move people and get results in the short-term, but the dissonance it creates is associated with toxic relationships and emotions such as anger, anxiety and fear. People are getting sick and tired of the greed, selfishness and lack of integrity of organizations and their leaders. People are expecting a change.

Leaders in business schools, organizations and in politics are taught to lead with their heads and not with their hearts. Leaders are expected to be strategic, rational, tough, bottom-line business people who focus on results. Yet, recent research on successful leaders and the current turbulent economic and social times calls out for a different style of leader — one that exhibits compassion and empathy.

Bill Taylor, writing in the Harvard Business Review blog network believes it is because of “the hunger among customers, employees and all of us to engage with companies on more than just dollars-and-cents terms. In a world that is being shaped by the relentless advance of technology what stand out are acts of compassion and connection that remind us what it means to be human.”

What’s the Difference Between Empathy and Compassion?

Compassion is not the same as empathy or altruism, though the concepts are related. While empathy refers more generally to our ability to take the perspective of and feel the emotions of another person, to put yourself in their shoes and imagine what they’re going through in that situation. Compassion is when those feelings and thoughts include the desire to help, to take action.

Neuroscientists Tania Singer and Olga Klimecki conducted studies comparing empathy and compassion. Two separate experiment groups were trained to practice either empathy or compassion. Their research revealed fascinating differences in the brain’s reaction to the two types of training. First, the empathy training activated motion in the insula (linked to emotion and self-awareness) and motion in the anterior cingulate cortex (linked to emotion and consciousness), as well as pain registering. The compassion group, however, stimulated activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex (connected to learning and reward in decision-making) as well as activity in the ventral striatum (also connected to the reward system).

Second, the two types of training led to very different emotions and attitudes toward action. The empathy-trained group actually found empathy uncomfortable and troublesome. The compassion group, on the other hand, created positivity in the minds of the group members. The compassion group ended up feeling kinder and more eager to help others than those in the empathy group.

While these words are close cousins, they are not synonymous with one another. Empathy means that you feel what a person is feeling. Sympathy means you can understand what the person is feeling. Compassion is the willingness to relieve the suffering of another.

Empathy is viscerally feeling what another feels. Thanks to what researchers have deemed “mirror neurons,” empathy may arise automatically when you witness someone in pain. For example, if you saw me slam a car door on my fingers, you may feel pain in your fingers as well. That feeling means your mirror neurons have kicked in.

Compassion takes empathy and sympathy a step further. When you are compassionate, you feel the pain of another (i.e., empathy) or you recognize that the person is in pain (i.e., sympathy), and then you do your best to alleviate the person’s suffering.

Thupten Jinpa, Ph.D., is the Dalai Lama’s principal English translator and author of the course Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT). Jinpa posits that compassion is a four-step process:

- Awareness of suffering.

- Sympathetic concern related to being emotionally moved by suffering.

- Wish to see the relief of that suffering.

- Responsiveness or readiness to help relieve that suffering.

In an organizational context, good leaders must be able to exhibit and practice both empathy and compassion, although the impact of compassion is more important.

Empathy

To better grasp what people mean when they talk about empathy, the most common uses for empathy fall in these categories:

- The type of empathy where we directly feel what others feel.

- The type of empathy where you imagine yourself in others’ shoes.

- The type of empathy where you imagine the world, or a situation, from someone else’s point of view rather than your own.

- The type of empathy that researchers sometimes call “mind reading.” It involves being good at reading others’ emotions and body language.

Over the last decade, neuroscientists have identified a 10-section “empathy circuit” in our brains which, if damaged, can curtail our ability to understand what other people are feeling. Evolutionary biologists like Frans de Waal have shown that we are social animals who have naturally evolved to care for each other, just like our primate cousins. And psychologists have revealed that we are primed for empathy by strong attachment relationships in the first two years of life.

But empathy doesn’t stop developing in childhood. We can nurture its growth throughout our lives—and we can use it as a radical force for social transformation. According to new research, it’s a habit we can cultivate to improve the quality of our own lives.

Many leadership theories suggest the ability to have and display empathy is an important part of leadership. Transformational leaders need empathy in order to show their followers that they care for their needs and achievement. Authentic leaders also need to have empathy in order to be aware of others Empathy is also a key part of emotional intelligence that several researchers believe is critical to being an effective leader.

TIME magazine went so far as to call empathy “the hottest trend in leadership.” And rightly so. Approximately 20% of U.S. companies now offer empathy training to their managers. According to a DDI study cited in the same article, the skills that had the strongest correlation with successful leadership were listening and responding. Walter Annenberg Chair in Communication and dean of the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California, Ernest J. Wilson III says empathy is “ the ‘attribute-prime’ of successful leaders.”

An empathetic leader is able to establish a connection with her teammates, encourage collaboration, and influence teammates to be more loyal to an organization. But on the flip side, her judgment may be clouded by her own biases and personal experiences — even her ethical judgment can become eroded. Sympathy is nice, but empathy is more effective when it comes to employee engagement. The same goes for being a better leader and colleague in the working world — studies show having empathy for employees can increase their satisfaction in the workplace. And, if you think your business practices empathy effectively, think again: less than 50 percent of employees in a recent Businessolver survey reported feeling that their companies were empathetic.

Simon Sinek titled his 2014 book Leaders Eat Last: Why Some Teams Pull Together and Others Don’t—a follow-up to his powerhouse Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. In Leaders Eat Last, Sinek proposes a concept of leadership that has little to do with authority, management acumen or even being in charge. True leadership, Sinek says, is about empowering others to achieve things they didn’t think possible. Exceptional organizations, he says, “prioritize the well-being of their people and, in return, their people give everything they’ve got to protect and advance the well-being of one another and the organization.”

In John Baldoni’s “How To Lead With Empathy (and When Not To)”, believes that a total lack of empathy is not positive, he believes that “empathy is the ability to have a heart, but leadership is the attribute to act on that heart when it matters.” Jill Kransny, who wrote “The Awesome Power of Empathy,” contends the best leaders at work are the ones who take time to listen to their employees, see other’s perspectives, and understand where an employee may be coming from.

Shelly Levitt writes in “Why the Empathetic Leader Is the Best Leader,”that helping others, expressing kindness, and empathy provides a sensation of feeling good. Furthermore, she states that by training to be more empathic and by acting more congenial, there is a building effect. “Daily practice of putting the well-being of others first has a compounding and reciprocal effect in relationships, in friendships, in the way we treat our clients and our colleagues.”.

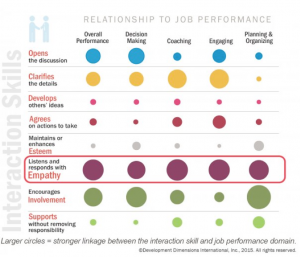

Global training giant Development Dimensions International (DDI) has studied leadership for 46 years. They believe that the essence of optimal leadership can be boiled down to having dozens of “fruitful conversations” with others, inside and outside your organization. Expanding on this belief, they assessed over 15,000 leaders from more than 300 organizations across 20 industries and 18 countries to determine which conversational skills have the highest impact on overall performance. The findings, published in their High Resolution Leadership report, are revealing.

While skills such as “encouraging involvement of others” and “recognizing accomplishments” are important, empathy–-rose to the top as the most critical driver of overall performance. Specifically, the ability to listen and respond with empathy (see graph below).

Ray Krznaric, author of Empathy: Why It Matters, and How to Get It, sums it up nicely: “Empathy in the modern workplace is not just about being able to see things from another perspective. It’s the cornerstone of teamwork, good innovative design, and smart leadership. It’s about helping others feel heard and understood.”

The Bad News

The DDI report reveals a dire need for leaders with the skill of empathy. Only four out of 10 frontline leaders assessed in their massive study were proficient or strong on empathy.

Richard S. Wellins, senior vice president of DDI and one of the authors of the High-Resolution Leadership report, had this to say in a Forbes interview a year ago: “We feel empathy is in serious decline. More concerning, a study of college students by University of Michigan researchers showed a 34 percent to 48 percent decline in empathic skills over an eight-year period. These students are our future leaders! We feel there are two reasons that account for this decline. Organizations have heaped more and more on the plates of leaders, forcing them to limit face-to-face conversations.”

Again, DDI research revealed that leaders spend more time managing than they do “interacting.” They wish they could double their time spent interacting with others. The second reason falls squarely on the shoulders of technology, especially mobile smart devices. These devices have become the de rigueur for human interactions.

Compassion

Historically, men have dominated the business landscape and still do today for the most part. Not surprisingly, male-oriented ideas and priorities—particularly dispassionate logical, rational problem solving perspectives—have dominated organizations. Conversely, love and compassion and are generally perceived to be female traits and perspectives, and, if seen in men, are viewed as a “weakness.”

There has been a revolution in organizational behavior literature in the past three decades focusing on the importance of emotions for employee attitudes, interpersonal relations and work performance. However, this research has neglected the basic emotions of compassionate love ( feelings of affection, compassion, empathy, caring and tenderness for others).

P.J. Frost, in a piece on compassion for the Journal of Management Inquiry, argues “As organizational researchers, we tend to see organizations and their members with little other than a dispassionate eye and training that inclines us toward abstractions that no include consideration of the dignity and humanity of those in our lens. Our hearts, our compassion, are not engaged and we end up being outside of and missing the humanity, the ‘aliveness’ of organizational life.”

Jacoba M. Lilius and her colleagues contend in their chapter of The Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship, conclude that organizational models that assume human nature consists only of individual self-interests have been extremely limiting and new research points to the fundamental role of empathetic concern and compassion not only in social life but in the workplace.

A predominant dispassionate, logical approach that distances itself from compassionate love, develops reward systems and training and development methods and the cycle reinforces itself. You will rarely see management training programs or employee manuals that address principles of tolerance, selflessness, kindness and compassionate love. When unloving, dispassionate behavior is modeled by the leader, this sets the tone for the entire organization, and when replicated across many organizations, sets a norm for business. It’s not that dispassionate, coldly logical ways of running organizations have not met with success, because they and their leaders have. But what has been the cost in terms of relationships, employee morale and happiness?

In an article for the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley, Emma Sepalla, director of the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education at Stanford University, cites the growing incidence of workplace stress among employees. She argues that a new field of research suggests when organizations promote an “ethic of compassion rather than a culture of stress, they may not only see a happier workplace, but also an upward bottom line.”

Claudio Fernandez-Araoz, writing in the Harvard Business Review Blogs, argues that organizations must develop a “culture of compassionate coaching.” This means not merely focusing coaching employees on their weaknesses, “and that creating a ‘culture of unconditional love’ binds the team together.”

Tim Sanders, author of the book, Love Is A Killer App, argues “those of us who use love as a point of differentiation in business will separate ourselves from our competitors just as world-class distance runners separate themselves from the rest of the pack.”

Dirk van Dierendonck and Kathleen Patterson, writing in the Journal of Business Ethics, take a virtues perspective and show how servant leadership may encourage a more meaningful and optimal human functioning with a strong sense of community to current-day organizations. In essence, they propose that a leader’s propensity for compassionate love will encourage a virtuous attitude in terms of humility, gratitude, forgiveness and altruism. This virtuous attitude will give rise to servant leadership behavior in terms of empowerment, authenticity, stewardship and providing direction.

Sigel G. Barsade at the Wharton School of Business and Olivia A. O’Neill at the University of Pennsylvania published an article in Administration Quarterly in which they describe their longitudinal study of the culture of compassionate love in organizations. They found compassionate love positively relates to employee satisfaction and teamwork and negatively relates to employee absenteeism and emotional exhaustion.

Barsade and O’Neill speculate that the reason for this is because in Western culture, the assumption is that love “stops at the office door, and that work relationships are not deep enough to be called love.” The authors contend most organizational culture literature has largely neglected emotions and there is no organizational theory that incorporates behavioral norms, values and deep underlying assumptions about the content of emotions themselves and their impact on employees. Instead, a focus on cognitive constructions of job satisfaction and employee engagement has been the focus.

In the book “Awakening Compassion at Work,” authors Monica Worline and Jane Dutton describe two different ways that compassion manifests itself in leadership practices. They describe “leading for compassion” as actions that leaders take when they use their position or personal influence to direct organizational resources that alleviate suffering. For example, when leaders sanction paid time off for employees to help volunteer for disaster relief projects, they are leading for compassion. Leading with compassion is an interpersonal endeavor between a leader and an individual. One leads with compassion when he or she is fully present with an employee who’s recently suffered a loss. Although you may not always be able to influence organizational change due to your leadership role in the company, you always have a choice to exhibit compassion in a one-to-one setting.

According to Rasmus Hougaard, Managing Director of Potential Project, leaders who dare to show compassion are rewarded with team members’ loyalty. He cites research by Professor Shimul Melvani, from the University of North Carolina’s Fliegler School of Business, who found that compassionate leaders have increased levels of engagement, and have more people willing to follow them.

“When we as leaders value the happiness of our people, they feel appreciated. They feel respected. And this makes them feel truly connected and engaged. It’s no accident that organizations with more compassionate leaders have stronger connections between people, better collaboration, more trust, stronger commitment to the organization, and lower turnover,” says Hougaard, whose consultancy provides leadership development training in the competencies of compassion, mindfulness and selflessness.

Of the over 1,000 leaders that Rasmus Hougaard, Jacqueline Carter and Louise Chester interviewed and reported on in the Harvard Business Review, 91% said compassion is very important for leadership, and 80% would like to enhance their compassion but do not know how. Compassion is clearly a hugely overlooked skill in leadership training.

Compassionate Leadership has emerged from the growing field of mindfulness, originally pioneered by Jon Kabat-Zinn as a means of reducing stress. The fact that compassion and leadership are rarely positively correlated is perhaps the very reason it’s resonating so widely. As global competition and heightened uncertainty has driven organizations to outsource, flatten and cut back (often quite mindlessly and heartlessly – the two tend to go hand in hand), people have become increasingly hungry for a deeper sense of meaning in their work and a closer connection between what they do and how it serves a greater good.

Compassion in the workplace could range from a dyadic act to a collective and organized act. Dyadic or individual compassion in the workplace is presented when an individual notices a colleague’s problem, feels empathy and takes action to help. This form of compassion depends on the compassionate person’s initiative to provide help and support and does not necessarily rely on any support from the organization.

Compassion at work may also take a collective form. In this form of compassion a group of colleagues gets involved in the compassionate act. Jason Kanov et al. identified

this as ‘organizational compassion’ which begins with an individual noticing a colleague’s problem, but becomes a social process with a group of colleagues acknowledging the presence of pain and feeling moved to take action in a collective way.

Roffey Park’s Compassion in the Workplace model identified the following elements of compassionate leadership in the workplace:

- Being alive to the suffering of others. Being sensitive to the well-being of others and noticing any change in their behavior is one of the important attributes of a compassionate person. It enables the compassionate person to notice when others need help. Noticing someone’s suffering could be difficult particularly in workplaces where people are busy with their work and preoccupied with their deadlines. Also depending on the work environment and the culture of the organization, people may tend to hide their pain from others.

- Being non-judgmental. A compassionate person does not judge the sufferer and accepts and validates the person’s experience. He or she recognizes that the experience of a single individual is part of the larger human experience and it is not a separate event only happening to this person. Judging people in difficulty – or worse condemning them – is one of the obstacles preventing us from understanding their situation and thereby being able to feel their pain.

- Tolerating personal distress. Distress tolerance is the ability to bear or to hold di cult emotions. Hearing about or becoming aware of someone’s dfficulty may distress a compassionate person but does not overwhelm that person to the extent that it stops them from taking action. People who feel overwhelmed by another person’s distress may simply turn away and may not be able to help or take the right action.

- Being empathetic. Feeling the emotional pain of the person who is suffering is another attribute of a compassionate person. Empathy involves understanding the sufferer’s pain and feeling it as if it were one’s own.

- Taking appropriate action. Feeling empathic towards someone encourages the observer to take action and to do something to help the sufferer. Customizing actions depending on the sufferer’s personal circumstances is also important. Taking the right action depends on the extent to which we have made e orts to know the sufferer.

Compassion Training

You weren’t born with a fixed amount of compassion. It turns out that compassion is a trainable skill, one that can be “exercised” like a muscle, says Dr. Richard J. Davidson of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Center for Investigating Healthy Minds. Dr. Davidson conducted a study to determine if everyday people could learn to feel compassion for different categories of people, including “difficult” people in their lives.

Using an online meditation training program for 30 minutes each day, study participants gradually learned to focus on feeling compassion for others. After two weeks of practice, participants’ brain scans showed higher activity for altruistic behaviors. Moreover, study participants who received compassion training were more likely to act generously towards strangers.

According to Fahri Karakas and Emine Sarigollo, “top leaders with higher ethical sensitivity evoke virtuous behavior in organizations. A compassionate leader initiates a cycle of positive change through 1) ethical decision-making 2) creating meaning and 3) inspiring hope and fostering courage for action that leaves a positive impact on the community. Genuine and intentional actions motivated by kindness result in shared benefits for the common good. Compassionate leaders nourish membership and use intentional attributes of love to enhance inclusion. They are moved by suffering and motivated by altruism to serve as a shining light to others. They give up their own goals in exchange for group decisions, do not need to know all the answers or be superior, and they listen instead of talk. Selfless leaders build relationships and respond to others to inspire higher levels of performance and purpose in their lives.

The road to becoming a compassionate leader requires self-reflection and personal transformation. Leaders who can evaluate their own strengths and weakness are better equipped to recognize and utilize the talents of others. They embrace employees as whole persons, discover human potential, create supportive teams, encourage positive engagement, and foster organizational growth and ethical membership in the community. There is a strong connection between compassionate leaders and ethical organizations: compassionate leaders act as catalysts.

A compassionate leader knows that to lead others she must be genuine and know her own heart. This requires 1) attention to the demands of ego; 2) recognition that the ego is a barrier to the deeper self; and, 3) courage to understand that without knowing oneself, one cannot attract respect, allegiance and the trust needed to guide others. The key to progress and positive change is the constant search for a more benevolent and transcendent self because there is a contagious nature to positive engagement at the organizational level.

Creating a Compassionate Workplace

In order for the capacity of compassion to emerge at an organizational level, policies and initiatives need to be put in place to encourage compassionate responses to employees’ emotional needs. Despite challenges in finding convergence across complex behavioral models, there is a growing interest both conceptually and empirically in how compassion can provide an account of organizational behavior more accurate than conventional mechanistic models. Compassionate organizing happens when individuals in an organization react and respond to human suffering in a coordinated way.

Compassion is conceptualized as a form of emotional work and is developed through the theoretical model of noticing, feeling and responding according to Katherine Miller. Noticing involves recognizing the needs of others, the process of feeling involves connecting empathetically, and responding involves verbal strategies and environmental structuring to balance emotional and informational content.

The Bottom Line

The business world and workplace has, for far too long, been a transactional, and sometimes heartless and soulless place. Recruiting, training and promoting leaders who exhibit and practice empathy and compassion will do much to increase meaning in work and enhance well being.

Copyright: Neither this article or a portion thereof may be reproduced in any print or media format without the express permission of the author.

Read my latest book: Eye of the Storm: How Mindful Leaders Can Transform Chaotic Workplaces, available in paperback and Kindle on Amazon and Barnes & Noble in the U.S., Canada, Europe and Australia and Asia.